Beyond the Quiet Life of a Natural Monopoly: Regulatory Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commercial & Technical Evolution of the Ferry

THE COMMERCIAL & TECHNICAL EVOLUTION OF THE FERRY INDUSTRY 1948-1987 By William (Bill) Moses M.B.E. A thesis presented to the University of Greenwich in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2010 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work”. ……………………………………………. William Trevor Moses Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Sarah Palmer Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Alastair Couper Date:……………………………. ii Acknowledgements There are a number of individuals that I am indebted to for their support and encouragement, but before mentioning some by name I would like to acknowledge and indeed dedicate this thesis to my late Mother and Father. Coming from a seafaring tradition it was perhaps no wonder that I would follow but not without hardship on the part of my parents as they struggled to raise the necessary funds for my books and officer cadet uniform. Their confidence and encouragement has since allowed me to achieve a great deal and I am only saddened by the fact that they are not here to share this latest and arguably most prestigious attainment. It is also appropriate to mention the ferry industry, made up on an intrepid band of individuals that I have been proud and privileged to work alongside for as many decades as covered by this thesis. -

Jaarregister 2005 HOV-Railnieuws

Jaarregister 2006 HOV-Railnieuws Jaargang 49 versie 12.0 N.B. 1) de cijfers vóór de haakjes verwijzen naar bladzijnummer(s), 2) de cijfers tussen de haakjes verwijzen naar het editienummer. ( Indien op- of aanmerkingen, mail naar: [email protected] of: [email protected] ) Deel 1: Stads- en regiovervoer: tram, sneltram, light rail, metro en bus Aachen (= Aken) 345-346(574) Adelaide 49(566), 313-314(573) Albtalbahn 285(572) Alexandrië 94(567) Algerije 91(567), 275(572), 313(573) Algiers 91(567), 275(572), 313(573) Alicante 387(575) Almaty 417(576) Almere connexxion 89(567) Alstom Transport 316(573) Ameland 126(568) Amsterdam 3-5(565), 41-43(566), 83-84(567), 121(568), 121-122(568), 159-162(569), 197-200(570), 233(571), 268-270(572), 307- 308(573), 335-339(574), 343(574), 377-378(575), 408- 411(576) Amsterdam gemeentebestuur 161(569) Amsterdam gratis OV 161(569), 307(573) Amsterdam infrastructuur 270(572), 308(573) Amsterdam koninginnedag 2006 161-162(569) Amsterdam Leidseplein 83-84(567) Amsterdam museumtramlijn 159(569), 162(569), 199(570), 233(571), 270(572), 308(573), 339(574) Amsterdam nieuw lijnennet 121(568) Amsterdam Noord-Zuidlijn 3(565), 41-42(566), 83(567), 161(569), 199(570), 233(571), 269(572), 307-308(573), 335(574), 336(574), 409-410(576) Amsterdam openbaar-vervoermuseum 3(565), 43(566), 122(568), 339(574) Amsterdam OV-politie 121-122(568) Amsterdam stadsmobiel 162(569) Amsterdam vandalisme 162(569) Amsterdam Weteringcircuit 161(569) Amsterdam Zuidas 409(576) Amsterdam zwartrijden in metro 269(572) Angers 279(572) -

Public Transport Procurement in Britain

This is a repository copy of Public Transport Procurement in Britain. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/159839/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Nash, C and Smith, A orcid.org/0000-0003-3668-5593 (2020) Public Transport Procurement in Britain. Research in Transportation Economics. ISSN 0739-8859 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2020.100847 © 2020 Elsevier Ltd. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/4.0/). Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Public Transport Procurement in Britain Chris Nash and Andrew Smith Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds Key words Bus; rail; franchising; competitive tendering; competition JEL classification R41 Abstract Britain is one of the countries with the most experience of alternative ways of procuring public transport services. From a situation where most public transport services were provided by publicly owned companies, it has moved to a situation where most are private. -

Competition Issues in Road Transport 2000

Competition Issues in Road Transport 2000 The OECD Competition Committee debated competition issues in road transport in October 2000. This document includes an executive summary and the documents from the meeting: an analytical note by Mr. Darryl Biggar for the OECD, written submissions from Australia, the Czech Republic, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Spain, Turkey, the United States, as well as an aide-memoire of the discussion. The road transport sector, an essential mode of transport in OECD economies, is conventionally divided into two, largely unrelated, parts – the road freight industry and the road passenger industry. The sectors under discussion – trucking, buses, and taxis – have quite different characteristics and scope for competition, which reflect inter alia differences in the timeliness and economies of scale and scope in operations. Trucking can sustain high level of competition and to some extent buses as well while there is some debate as to how and what form of competition can be introduced in taxis. As in the air transport industry, international trucking is governed by restrictive bilateral treaties. Most countries have liberalised their domestic trucking sector, removing controls on entry and prices. In the bus industry, long-distance bus services are liberalised in some countries while intra-city or local buses are very rarely liberalised. The taxi industry appears at first sight to be competitive with many buyers and many sellers. Structural Reform in the Rail Industry (2005) Competition Policy and the Deregulation of Road Transport (1990) Unclassified DAFFE/CLP(2001)10 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 22-May-2001 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English - Or. -

À La Recherche De La Continuité Territoriale Entre Londres Et Le

183 DuNight-Ferry à Eurostar:à la recherchede la continuitéterritoriale entreLondres et le continent FromNight Ferry to Eurostar: ln searchof the territorialcontinuity betweenLondon and thecontinent Etienne AUPHAN Université de Nancy 2 UFR des Sciences Historiques et Géographiques BP 3397 - 54015 - NANCY - France Résumé : La liaison entre Londres et le continent a fait l'objet, depuis le siècle dernier, et surtout depuis 25 ans, d'une recherche toujours plus poussée de formules se rapprochant de la continuité territoriale . Pour le transport des personnes, se sont ainsi notamment succédés la formule des gares maritimes et des trains-ferries traduisant le triomphe chi couple train-bateau, les car-ferries, consacrant le règne de l'automobile , les aéroglisseurs exprimant l'exigence de vitesse, et enfin le tunnel ferroviaire qui assure une continuité territoriale presque parfaite, mais paradoxalement au profit du rail, instaurant ainsi de nouveaux rapports intermodaux, aux conséquences sans doute encore mal mesurées sur le fonctionnement de l'espace littoral et w système de transport en ·général. Mots-clés France - Royaume-Uni - Tunnel sous la Manche - Transports intermodaux - Continuité territoriale Abstract : The aim of linking London to the continent has, since the last century and above during the last 25 years , been the object of a search for ever more advanced methods getting ever closer to a land link. For the transport of people, a number of methods have succeeded each other : ferry ports and rail-ferries reflected the triumph of the train-boat partnership, the car-ferries manifested the era of the car, hovercraft expressed the need for speed and, finally, the rail tunnel which assures an almost perfect territorial link. -

Eighth Annual Market Monitoring Working Document March 2020

Eighth Annual Market Monitoring Working Document March 2020 List of contents List of country abbreviations and regulatory bodies .................................................. 6 List of figures ............................................................................................................ 7 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 9 2. Network characteristics of the railway market ........................................ 11 2.1. Total route length ..................................................................................................... 12 2.2. Electrified route length ............................................................................................. 12 2.3. High-speed route length ........................................................................................... 13 2.4. Main infrastructure manager’s share of route length .............................................. 14 2.5. Network usage intensity ........................................................................................... 15 3. Track access charges paid by railway undertakings for the Minimum Access Package .................................................................................................. 17 4. Railway undertakings and global rail traffic ............................................. 23 4.1. Railway undertakings ................................................................................................ 24 4.2. Total rail traffic ......................................................................................................... -

Hessenschiene Nr. 108 (PDF)

HESSEN SCHIENE Nr. 108 Juli - September 2017 • Aus für Güterstrecke Altenkirchen – Selters? • Sachstand Frankfurt Rhein-MainPlus • Neue 10-Minuten-Garantie des RMV 4<BUFHMO=iaciai>:ltZKZ 04032 D: 2,80 Euro Seite 2 Karikatur: Jürgen Janson Impressum Erhältlich bei den Bahnhofsbuchhandlungen Bad Herausgeber Pro Bahn & Bus e.V. Kreuznach, Bad Nauheim, Darmstadt Hbf, Frankfurt Redaktionell Friedrich Lang (M) Hbf, Frankfurt (M) Süd, Frankfurt (M) Höchst, verantwortlich [email protected] Friedberg (Hessen), Fulda, Gießen, Göttingen, Hanau Hbf, Kassel Hbf, Kassel-Wilhelmshöhe, Limburg, Layout Jürgen Lerch Koblenz Hbf, Mainz Hbf, Marburg, Offenbach (M) Hbf, Kontakt Bahnhofstraße 102 Rüsselsheim, Wiesbaden Hbf 36341 Lauterbach Abonnement: Acht Ausgaben 18,00 Euro Tel. & Fax (06641) 6 27 27 (Deutschland); 26,00 Euro (Ausland / Luftpost). [email protected] Der Bezug ist für Mitglieder von Pro Bahn & Bus www.probahn-bus.org kostenfrei. AG Gießen VR 3732 Es gilt Anzeigenpreisliste Nr. 8 vom 1. Dez. 2010 Druck Druckhaus Gratzfeld, Butzbach Auflage 1400 Exemplare Nachdruck, auch auszugsweise, nur mit Genehmi- gung des Herausgebers. Der Herausgeber ist Mitarbeiter dieser Ausgabe: Hermann Hoffmann, berechtigt, veröffentlichte Beiträge in eigenen Friedrich Lang, Jürgen Lerch, Hans-Peter Günther, gedruckten und elektronischen Produkten zu Jürgen Schmied, Andreas Christopher, Oliver Günther verwenden und eine Nutzung Dritten zu gestatten. Redaktionsschluss nächste Ausgabe: 04.09.2017 Eine Verwertung urheberrechtlich geschützter Erscheinungsweise: -

View Annual Report

National Express Group PLC Group National Express National Express Group PLC Annual Report and Accounts 2007 Annual Report and Accounts 2007 Making travel simpler... National Express Group PLC 7 Triton Square London NW1 3HG Tel: +44 (0) 8450 130130 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7506 4320 e-mail: [email protected] www.nationalexpressgroup.com 117 National Express Group PLC Annual Report & Accounts 2007 Glossary AGM Annual General Meeting Combined Code The Combined Code on Corporate Governance published by the Financial Reporting Council ...by CPI Consumer Price Index CR Corporate Responsibility The Company National Express Group PLC DfT Department for Transport working DNA The name for our leadership development strategy EBT Employee Benefit Trust EBITDA Normalised operating profit before depreciation and other non-cash items excluding discontinued operations as one EPS Earnings Per Share – The profit for the year attributable to shareholders, divided by the weighted average number of shares in issue, excluding those held by the Employee Benefit Trust and shares held in treasury which are treated as cancelled. EU European Union The Group The Company and its subsidiaries IFRIC International Financial Reporting Interpretations Committee IFRS International Financial Reporting Standards KPI Key Performance Indicator LTIP Long Term Incentive Plan NXEA National Express East Anglia NXEC National Express East Coast Normalised diluted earnings Earnings per share and excluding the profit or loss on sale of businesses, exceptional profit or loss on the -

Overseas Rail-Marine Bibliography

Filename: Dell/T43/bibovrmi.wpd Version: March 29, 2006 OVERSEAS RAIL-MARINE BIBLIOGRAPHY Compiled by John Teichmoeller With Assistance from: Ross McLeod, Phil Sims, Bob Parkinson, and Paul Lipiarski, editorial consultants. Introduction This installment is the next-to-last in our series of regional bibliographies that have covered the Great Lakes (Transfer No. 9), East Coast (Transfer No. 10 and 11), Rivers and Gulf (Transfer No. 18), Golden State [California] (Transfer No. 27) and Pacific Northwest (Transfer No. 36). The final installment, “Miscellaneous,” will be included with Transfer No. 44. It was originally our intention to begin the cycle again, reissuing and substantially upgrading the bibliographies with the additional material that has come to light. However, time and spent energy have taken their toll, so future updates will have to be in some other form, perhaps through the RMIG website. Given the global scope of this installment, I have the feeling that this is the least comprehensive of any sections compiled so far, especially with regard to global developments in the last thirty years. I have to believe there is a much more extensive literature, even in English, of rail-marine material overseas than is presented here. Knowing the “train ferry” (as they are called outside of North America) operations in Europe, Asia and South America, there must be an extensive body of non-English literature about these of which I am ignorant. However, as always, we publish what we have. Special thanks goes to Bob Parkinson for combing 80+ years of English technical journals. Moreover, I have included some entries here that may describe auto ferries and not car ferries, but since I have not seen some of the articles I am unsure; I have shared Bob’s judgements in places. -

List of Numeric Codes for Railway Companies (RICS Code) Contact : [email protected] Reference : Code Short

List of numeric codes for railway companies (RICS Code) contact : [email protected] reference : http://www.uic.org/rics code short name full name country request date allocation date modified date of begin validity of end validity recent Freight Passenger Infra- structure Holding Integrated Other url 0006 StL Holland Stena Line Holland BV NL 01/07/2004 01/07/2004 x http://www.stenaline.nl/ferry/ 0010 VR VR-Yhtymä Oy FI 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.vr.fi/ 0012 TRFSA Transfesa ES 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 04/10/2016 x http://www.transfesa.com/ 0013 OSJD OSJD PL 12/07/2000 12/07/2000 x http://osjd.org/ 0014 CWL Compagnie des Wagons-Lits FR 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.cwl-services.com/ 0015 RMF Rail Manche Finance GB 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.rmf.co.uk/ 0016 RD RAILDATA CH 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.raildata.coop/ 0017 ENS European Night Services Ltd GB 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x 0018 THI Factory THI Factory SA BE 06/05/2005 06/05/2005 01/12/2014 x http://www.thalys.com/ 0019 Eurostar I Eurostar International Limited GB 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.eurostar.com/ 0020 OAO RZD Joint Stock Company 'Russian Railways' RU 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://rzd.ru/ 0021 BC Belarusian Railways BY 11/09/2003 24/11/2004 x http://www.rw.by/ 0022 UZ Ukrainski Zaliznytsi UA 15/01/2004 15/01/2004 x http://uz.gov.ua/ 0023 CFM Calea Ferată din Moldova MD 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://railway.md/ 0024 LG AB 'Lietuvos geležinkeliai' LT 28/09/2004 24/11/2004 x http://www.litrail.lt/ 0025 LDZ Latvijas dzelzceļš LV 19/10/2004 24/11/2004 x http://www.ldz.lv/ 0026 EVR Aktsiaselts Eesti Raudtee EE 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://www.evr.ee/ 0027 KTZ Kazakhstan Temir Zholy KZ 17/05/2004 17/05/2004 x http://www.railway.ge/ 0028 GR Sakartvelos Rkinigza GE 30/06/1999 30/06/1999 x http://railway.ge/ 0029 UTI Uzbekistan Temir Yullari UZ 17/05/2004 17/05/2004 x http://www.uzrailway.uz/ 0030 ZC Railways of D.P.R.K. -

Publicity Material List

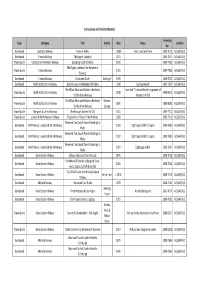

Early Guides and Publicity Material Inventory Type Company Title Author Date Notes Location No. Guidebook Cambrian Railway Tours in Wales c 1900 Front cover not there 2000-7019 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook Furness Railway The English Lakeland 1911 2000-7027 ALS5/49/A/1 Travel Guide Cambrian & Mid-Wales Railway Gossiping Guide to Wales 1870 1999-7701 ALS5/49/A/1 The English Lakeland: the Paradise of Travel Guide Furness Railway 1916 1999-7700 ALS5/49/A/1 Tourists Guidebook Furness Railway Illustrated Guide Golding, F 1905 2000-7032 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook North Staffordshire Railway Waterhouses and the Manifold Valley 1906 Card bookmark 2001-7197 ALS5/49/A/1 The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Inscribed "To Aman Mosley"; signature of Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1908 1999-8072 ALS5/29/A/1 Staffordshire Railway chairman of NSR The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Moores, Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1891 1999-8083 ALS5/49/A/1 Staffordshire Railway George Travel Guide Maryport & Carlisle Railway The Borough Guides: No 522 1911 1999-7712 ALS5/29/A/1 Travel Guide London & North Western Railway Programme of Tours in North Wales 1883 1999-7711 ALS5/29/A/1 Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7680 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7681 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, -

Railnews 2009 Directory

Railnews 2009 Directory 1.Train Operators Full listing of all UK passenger & freight operating companies in the UK 2. Recruitment & Training Companies & government-run organisations focused on training and recruitment within the UK rail industry 3. Industry Stakeholders Government & independent organisations including Network Rail and the BTP 4. Industry Suppliers UK and International companies supplying, manufacturing and serving the UK industry 5. Industry Representatives Rail and transport unions Railnews Ltd, 180-186 Kings Cross Road, Kings Cross Business Centre, London, WC1X 9DE | 020 7689 1610 | www.railnews.co.uk | [email protected] Train Operators Train Operators ARRIVA PLC Fax: 01603 214 517 Managing Director UK Trains: Bob Holland Email: [email protected] EAST MIDLAND TRAINS (Stagecoach Group) Telephone: 0191 520 4000 Website: www.c2c-online.co.uk Managing Director: Tim Shoveller Email: [email protected] Postal Address: c2c Rail Ltd, 207 Old Street, London, EC1V 9NR Telephone: 08457 125 678 Website: www.arriva.co.uk Email: [email protected] Postal Address: Admiral Way, Doxford International Business Park, CHILTERN RAILWAYS (DB Regio/Laing Rail) Website: www.eastmidlandstrains.co.uk Sunderland, SR3 3XP Chairman: Adrian Shooter Postal Address: East Midlands Trains, 1 Prospect Place, Millennium Franchises: Arrive Trains Wales; CrossCountry. Telephone: 08456 005 165 Way, Pride Park, Derby, DE24 8HG Fax: 01296 332126 ARRIVA TRAINS WALES/TRENAU ARRIVA CYMRU Website: www.chilternrailways.co.uk EUROSTAR Managing Director: Tim Bell Postal Address: The Chiltern Railway Company Ltd, 2nd floor, Eurostar (UK) Ltd is part of Eurostar Group. the UK company is owned Telephone: 0845 6061660 Western House, 14 Rickfords Hill, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, HP20 by London and Continental Railways and managed by Inter Capital Fax: 02920 645349 2RX and Regional Rail Ltd, a consortium of National Express Group, Email: [email protected] Belgian Railways, French Railways and British Airways.