NASCENT NATIONALISM in the PRINCELY STATES While Political

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Question Bank Mcqs TYBA Political Science Semester V 2019-20 Paper-6 Politics of Modern Maharashtra

Question Bank MCQs TYBA Political Science Semester V 2019-20 Paper-6 Politics of Modern Maharashtra 1. Who founded the SNDT University for women in 1916? a) M.G.Ranade b) Dhondo Keshav Karve c) Gopal Krishna Gokhale d) Bal Gangadhar Tilak 2. Who was associated with the Satyashodhak Samaj? a) Sri Narayan Guru b) Jyotirao Phule c) Dr. B. R. Ambedkar d) E.V. Ramaswamy Naicker 3. When was the Indian National Congress established? a) 1875 b) 1885 c) 1905 d) 1947 4. Which Marathi newspaper was published by Bal Gangadhar Tilak a) Kesari b) Poona Vaibhav c) Sakal d) Darpan 5. Which day is celebrated as the Maharashtra Day? a) 12th January b) 14th April c) 1st May d) 2nd October 6. Under whose leadership Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti was founded? a) Keshavrao Jedhe b) S. A. Sange c) Uddhavrao Patil d) Narayan Ganesh Gore 7. When did the Bilingual Bombay State come into existence? a) 1960 b) 1962 c) 1956 d) 1947 8. Which one of the following city comes under Vidarbha region? a) Nagpur b) Poona c) Aurangabad d) Raigad 9. Till 1948 Marathwada region was part of which of the following? a) Central Province and Berar b) Bombay State c) Hyderabad State d) Junagad 10. Dandekar Committee dealt with which of the following issues? a) Maharashtra’s Educational policy b) The problem of imbalance in development between different regions of Maharashtra c) Trade and commerce policy of Maharashtra d) Agricultural policy 11. Which one of the following is known as the financial capital of India? a) Pune b) Mumbai c) Nagpur d) Aurangabad 12. -

History and Political Science

The Coordination Committee formed by GR No. Abhyas - 2116/(Pra.Kra.43/16) SD - 4 Dated 25.4.2016 has given approval to prescribe this textbook in its meeting held on 29.12.2017 and it has been decided to implement it from the educational year 2018-19. HISTORY AND POLITICAL SCIENCE STANDARD TEN Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, Pune. The digital textbook can be obtained through DIKSHA App on a smartphone by using the Q. R. Code given on title page of the textbook and useful audio-visual teaching-learning material of the relevant lesson will be available through the Q. R. Code given in each lesson of this textbook. First Edition : 2018 © Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Reprint : Research, Pune - 411 004. The Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research reserves October 2020 all rights relating to the book. No part of this book should be reproduced without the written permission of the Director, Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, ‘Balbharati’, Senapati Bapat Marg, Pune 411004. History Subject Committee Authors History Political Science Dr Sadanand More, Chairman Dr Shubhangana Atre Dr Vaibhavi Palsule Shri. Mohan Shete, Member Dr Ganesh Raut Shri. Pandurang Balkawade, Member Dr Shubhangana Atre, Member Translation Scrutiny Dr Somnath Rode, Member Shri. Bapusaheb Shinde, Member Dr Shubhangana Atre Dr Manjiri Bhalerao Dr Vaibhavi Palsule Dr Sanjot Apte Shri. Balkrishna Chopde, Member Shri. Prashant Sarudkar, Member Cover and Illustrations Shri. Mogal Jadhav, Member-Secretary Shri. Devdatta Prakash Balkawade Typesetting Civics Subject Committee DTP Section, Balbharati Dr Shrikant Paranjape, Chairman Paper Prof. -

![Poona Sarvajanik Sabha Founded - [April 2, 1870] This Day in History](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2228/poona-sarvajanik-sabha-founded-april-2-1870-this-day-in-history-712228.webp)

Poona Sarvajanik Sabha Founded - [April 2, 1870] This Day in History

Poona Sarvajanik Sabha Founded - [April 2, 1870] This Day in History On 2nd April 1870, Poona Sarvajanik Sabha was founded. In this edition of This Day in History, you can read about the important socio-political organisation Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, an early platform where educated Indians expressed their opinions and demands from the British government. This is a part of UPSC Syllabus on history. Aspirants would find this article very helpful while preparing for the IAS Exam. Background of Poona Sarvajanik Sabha for UPSC 1. The Poona Sarvajanik Sabha was established on 2 April 1870 at Poona originally because of the discontent of the people over the running of a local temple. 2. The Deccan Association formed in 1850 and the Poona Association formed in 1867 had become defunct within a few years and the western educated residents of Poona felt the need for a modern socio-political organisation. 3. Mahadev Govind Ranade, an eminent lawyer and scholar from the Bombay Presidency was also a keen social reformer. He played a major part in the formation of the Sarvajanik Sabha. 4. The other key members who helped in its formation were Bhawanrao Shriniwasrao Pant Pratinidhi (ruler of the Aundh State who was also the organisation’s first president), Ganesh Vasudeo Joshi and S H Chiplunkar. 5. Other important members of the Sabha included M M Kunte, Vishnu M Bhide, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Gopal Hari Deshmukh. The members were mostly from the educated middle class of society and comprised of lawyers, inamdars, pensioners, pleaders, teachers, journalists and government servants in the judicial and education departments. -

India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures

India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures by Ranjit Deshmukh A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Energy and Resources in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Duncan Callaway, Chair Professor Severin Borenstein Dr. Michael Milligan Professor Daniel M. Kammen Professor Meredith Fowlie Fall 2016 India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures Copyright 2016 by Ranjit Deshmukh 1 Abstract India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures by Ranjit Deshmukh Doctor of Philosophy in Energy and Resources University of California, Berkeley Professor Duncan Callaway, Chair Decarbonizing its electricity sector through ambitious targets for wind and solar is India's major strategy for mitigating its rapidly growing carbon emissions. In this dissertation, I explore the economic, social, and environmental impacts of wind and solar generation on India's future low-carbon electricity system, and strategies to mitigate those impacts. In the first part, I apply the Multi-criteria Analysis for Planning Renewable Energy (MapRE) approach to identify and comprehensively value high-quality wind, solar photovoltaic, and concentrated solar power resources across India in order to support multi-criteria prioritiza- tion of development areas through planning processes. In the second part, I use high spatial and temporal resolution models to simulate operations of different electricity system futures for India. In analyzing India's 2022 system, I find that the targets of 100 GW solar and 60 GW wind set by the Government of India that are likely to generate 22% of total annual electricity, can be integrated with very small curtailment (approximately 1%). -

INDIA by Prachi Deshmukh Odhekar

INDIA by Prachi Deshmukh Odhekar Odhekar, P. D. (2012). India. In C. L. Glenn & J. De Groof (Eds.), Balancing freedom, autonomy and accountability in education: Volume 4 (91-108). Tilburg, NL: Wolf Legal Publishers. Overview Before 1976, education was the exclusive responsibility of the states, and state governments have been major providers of elementary education since independence. However, differences in the emphasis put on education and investment and implementation of educational programs accentuated disparities among states in educational attainment. In 1976, in order to overcome these disparities among states, a constitutional amendment added education to the concurrent list, meaning that central and state governments will bear equal responsibility for providing education henceforth. However, after this amendment the actual role of states as primary provider of education largely remained unchanged, while the central government worked on building the uniform character of education across the nation by reinforcing the national and integrated character of education, maintaining quality and standards including those of the teaching profession at all levels, and promoting the study and monitoring of the educational requirements of the country. The Government of India issued National Education Policies in 1968 and 1986. These policies made primary education a national priority and envisaged an increase in resources committed to improve access and quality of education. The central government also launched several centrally sponsored schemes to improve primary education across the country. In the mid-1990s, a series of District Primary Education Programs (DPEP) were introduced in districts where female literacy rates were low. The DPEPs pioneered new initiatives to bring out-of-school children into school, and were the first to decentralize the planning for primary education and actively involve communities. -

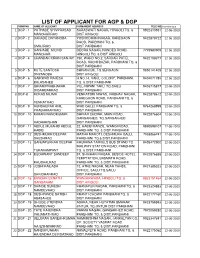

List of Applicant for Agp &

LIST OF APPLICANT FOR AGP & DGP FORM NO NAME OF ALLICANT PARMANENT ADDRESS TELE NO Interview date 1 DGP - 1 PATHADE SHIVPRASAD SARASWATI NAGAR, HINGOLI TQ. & 9922310551 12-06-2019 MANOHARRAO DIST.HINGOLI 2 DGP - 2 DARADE DNYANOBA YOSHODHAN NAGAR, KAREGAON 9422878722 12-06-2019 RAOD, PARBHANI TQ. & UMAJIRAO DIST.PARBHANI 3 DGP - 3 GANJARE MILIND DEORA NAGAR, NANDED ROAD, 7775980909 12-06-2019 MANOHAR HINGOLI TQ. & DIST.HINGOLI 4 DGP - 4 CHANDAK KIRAN SANJAY 150, WARD NO.2, SARDAR PATEL 9422108377 12-06-2019 ROAD, KACHI BAZAR, PARBHANI TQ. & DIST.PARBHANI 5 DGP - 5 KUTE SANTOSH SHIVANI BK, TQ.SENGAON 9850141405 12-06-2019 DNYANOBA DIST.HINGOLI 6 DGP - 6 GAIKWAD RAJESH H.NO.14, VAKIL COLONY, PARBHANI. 9404071783 12-06-2019 BALASAHEB TQ. & DIST.PARBHANI 7 DGP - 7 GIRAM PRABHAKAR VILL-NIPANI TAKLI TQ.SAILU 9403715877 12-06-2019 DIGAMBARRAO DIST.PARBHANI 8 DGP-8 KOKAD NILIMA VENKATDRI NIWAS, VAIBHAV NAGAR, 9422878612 12-06-2019 KAREGAON ROAD, PARBHANI TQ. & VENKATRAO DIST.PARBHANI 9 DGP - 9 AUNDHEKAR ANIL WAD GALLI, PARBHANI TQ. & 9764268999 12-06-2019 PRABHAKARRAO DIST.PARBHANI 10 DGP - 10 KAKANI NANDKUMAR SHIVAJI CHOWK, MAIN ROAD, 9422876604 12-06-2019 GANGAKHED, TQ.GANGAKHED RADHAKISHAN DIST.PARBHANI 11 DGP - 11 ABDUL MUJAHID ABDUL 22, HABIB MANZIL, WANGI ROAD, 9890598107 12-06-2019 HABIB PARBHANI TQ. & DIST.PARBHANI 12 DGP - 12 DESHMUKH DEEPAK MATHA MAROTI, DESHMUKH GALLI, 7038866741 12-06-2019 SHESHRAO PARBHANI TQ.& DIST.PARBHANI 13 DGP - 13 GANJAPURKAR DEEPAK KHURANA TARVELS BUS STAND TO 9405472900 12-06-2019 RAILWAY STATION ROAD, PARBHANI TUKARAMPANT TQ. & DIST.PARBHANI 14 DGP - 14 BUDHWANT SANDEEP 57, SHRIHARI NAGAR, BESIDE HOTEL 9422876655 12-06-2019 TEMPTATION, BASMATH ROAD, KHUSHALRAO PARBHANI TQ. -

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798. -

Impact Factor – 3.452 ISSN – 2348-7143

I N Impact Factor – 3.452 ISSN – 2348-7143 T INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH FELLOWS ASSOCIATION’S E R N RESEARCH JOURNEY Multidisciplinary International E-research Journal A T PEER REFREED & INDEXED JOURNAL I April 2018 O Special Issue – LVII [A] N LIFE & MISSION OF A BHARATRATNA DR. B.R. AMBEDKAR L Editorial Board of the Special Issue R Guest Editor: E Dr. Leena Pandhare Principal, Late Bindu Ramrao Deshmukh S Arts and Commerce Mahila Mahavidyalaya, E Nashik Road A Executive Editor: R Tejesh Beldar Assistant Professor, Dept. of English, C Late Bindu Ramrao Deshmukh Arts & H Commerce Mahila Mahavidyalaya, Nashik Road F Assistant Editors: E Bhaskar Narwate and Dr. Minal Barve Late Bindu Ramrao Deshmukh Arts and L Commerce Mahila Mahavidyalaya, L Nashik Road O Chief Editor: W Dr. Dhanraj T. Dhangar, Assist. Prof. (Marathi) S MGV‟s Arts and Commerce College, Yeola, Dist – Nashik [M.S.] INDIA A S This Journal is indexed in : S - University Grants Commission (UGC) List No. 40705 & 44117 O - Scientific Journal Impact Factor (SJIF) C - Cosmoc Impact Factor (CIF) - Global Impact Factor (GIF) I - Universal Impact Factor (UIF) A - International Impact Factor Services (IIFS) T - Indian Citation Index (ICI) - Dictionary of Research Journal Index (DRJI) I O N For Details Visit To : www.researchjourney.net SWATIDHAN PUBLICATIONS S ‘RESEARCH JOURNEY’ International Multidisciplinary E- Research Journal ISSN : Impact Factor - (CIF ) - 3.452, (SJIF) – 3.009, (GIF) –0.676 (2013) 2348-7143 Special Issue 57 [A]: Life & Mission of Bharatratna Dr. B. R. Ambedkar April UGC Approved No. 40705 & 44117 2018 Impact Factor – 3.452 ISSN – 2348-7143 INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH FELLOWS ASSOCIATION’S RESEARCH JOURNEY Multidisciplinary International E-Research Journal PEER REFREED & INDEXED JOURNAL April 2018 Special Issue – LVII [A] LIFE & MISSION OF BHARATRATNA DR. -

The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India

chapter 1 Caste Radicalism and the Making of a New Political Subject In colonial India, print capitalism facilitated the rise of multiple, dis- tinctive vernacular publics. Typically associated with urbanization and middle-class formation, this new public sphere was given material form through the consumption and circulation of print media, and character- ized by vigorous debate over social ideology and religio-cultural prac- tices. Studies examining the roots of nationalist mobilization have argued that these colonial publics politicized daily life even as they hardened cleavages along fault lines of gender, caste, and religious identity.1 In west- ern India, the Marathi-language public sphere enabled an innovative, rad- ical form of caste critique whose greatest initial success was in rural areas, where it created novel alliances between peasant protest and anticaste thought.2 The Marathi non-Brahmin public sphere was distinguished by a cri- tique of caste hegemony and the ritual and temporal power of the Brah- min. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, Jotirao Phule’s writings against Brahminism utilized forms of speech and rhetorical styles asso- ciated with the rustic language of peasants but infused them with demands for human rights and social equality that bore the influence of noncon- formist Christianity to produce a unique discourse of caste radicalism.3 Phule’s political activities, like those of the Satyashodak Samaj (Truth Seeking Society) he established in 1873, showed keen awareness of trans- formations wrought by colonial modernity, not least of which was the “new” Brahmin, a product of the colonial bureaucracy. Like his anticaste, 39 40 Emancipation non-Brahmin compatriots in the Tamil country, Phule asserted that per- manent war between Brahmin and non-Brahmin defined the historical process. -

The First Anglo-Maratha War Third Phase (1779-1783

THE FIRST ANGLO-MARATHA WAR THIRD PHASE (1779-1783) Chapter VII - THE SsiGOND BORGHAT BXPSDITION (1781) For geographiciO., rtfargncts^ » •« Map Nog. Xb W 1 9 . attached at the beginning of this chapter, bttween pp. 251«2^2. nlso see Mao No. 12. attached at the beginning of chapter V. between p p . 15^-155. M A P NO. 16 SECOND BORGHAT EXPEDITION (l78l)- ^UTES OF march of the TWO ARMIES DlSPOSlT»OK OF THE MARATHA TROOPS CAMPIN& GROUND ROUTE OF THE BRITISH ARMy UP TO KHANPALA ^^^ESCARPMENT [ h ^ = HARJPANnr PHADKE i RBj: PARASHURAMBHAU [t h I- TUK0J{ HOLKAR p a t w a r d h a h M AP NO. 17. M A I N C A M P euMMtT or BORGHAT SRITJSH THE MARATMA6 POaiTtONS a d v a m c e g u a r d GODDARD'S MAIN .OP THE MARATMAS C PArWARDHAN , pwaDke CAMP p a n a s c a h d — wCL»tAR JCtHl ^ KWANDALAv h o r o n h a 3 (SOO FT ■V a 6ovE « E A U E V ' E U •\ REAR BASE OF GODDARD aeCOND BOFX3HAT EXPEOm ON C17ai) SECTION F IR S T T A C T I C A L PL>swN O F T H E M A R A T H A S 9 c /M .e : i^s 2HICKS KHOPOLI QFRONTAU ATTACK O N THE ENEMY- FE8-I7«t ;> V4te~lGHT IN FEET / eUMKlT CF 5CRGHAT CGCDDARD'S BAJIPAHT CAMP) ✓ HAf?lPANT n P^IADK E ' w - MSU > I. lADVANr.e: > «,-t-20CXJ' ^ sl mp o ! ) / / /S»» - « *A i ■ -w- ^UART> OF THE MARATHAe Tu k .0J! PO&ITtOKJS < k A R L £ HOiKAfff MAtM CAN-P <0R0nH4' r C F T M E A N M A R A T H A ^ . -

Department of History

H.H. THE RAJAHA’S COLLEGE (AUTO), PUDUKKOTTAI - 622001 Department of History II MA HISTORY HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1947 C.E THIRD SEMESTER 18PHS7 MA HISTORY SEMESTER : III SUB CODE : 18PHS7 CORE COURSE : CCVIII CREDIT : 5 HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1947 C.E Objectives ● To understand the colonial hegemony in India ● To Inculcate the knowledge of solidarity shown by Indians against British government ● To know about the social reform sense through the historical process. ● To know the effect of the British rule in India. ● To know the educational developments and introduction of Press in India. ● To understand the industrial and agricultural bases set by the British for further developments UNIT – I Decline of Mughals and Establishment of British Rule in India Sources – Decline of Mughal Empire – Later Mughals – Rise of Marathas – Ascendancy under the Peshwas – Establishment of British Rule – the French and the British rivalry – Mysore – Marathas Confederacy – Punjab Sikhs – Afghans. UNIT – II Structure of British Raj upto 1857 Colonial Economy – Rein of Rural Economy – Industrial Development – Zamindari system – Ryotwari – Mahalwari system – Subsidiary Alliances – Policy on Non intervention – Doctrine of Lapse – 1857 Revolt – Re-organization in 1858. UNIT – III Social and cultural impact of colonial rule Social reforms – English Education – Press – Christian Missionaries – Communication – Public services – Viceroyalty – Canning to Curzon. ii UNIT – IV India towards Freedom Phase I 1885-1905 – Policy of mendicancy – Phase II 1905-1919 – Moderates – Extremists – terrorists – Home Rule Movement – Jallianwala Bagh – Phase III 1920- 1947 – Gandhian Era – Swaraj party – simon commission – Jinnah‘s 14 points – Partition – Independence. UNIT – V Constitutional Development from 1773 to 1947 Regulating Act of 1773 – Charter Acts – Queen Proclamation – Minto-Morley reforms – Montague Chelmsford reforms – govt.