The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (APO)

E-Book - 22. Checklist - Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (A.P.O) By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 22. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 8th May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 27 Nos. Date/Year Details of Issue 1 2 1971 - 1980 1 01/12/1954 International Control Commission - Indo-China 2 15/01/1962 United Nations Force - Congo 3 15/01/1965 United Nations Emergency Force - Gaza 4 15/01/1965 International Control Commission - Indo-China 5 02/10/1968 International Control Commission - Indo-China 6 15.01.1971 Army Day 7 01.04.1971 Air Force Day 8 01.04.1971 Army Educational Corps 9 04.12.1972 Navy Day 10 15.10.1973 The Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers 11 15.10.1973 Zojila Day, 7th Light Cavalary 12 08.12.1973 Army Service Corps 13 28.01.1974 Institution of Military Engineers, Corps of Engineers Day 14 16.05.1974 Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services 15 15.01.1975 Armed Forces School of Nursing 03.11.1976 Winners of PVC-1 : Maj. Somnath Sharma, PVC (1923-1947), 4th Bn. The Kumaon 16 Regiment 17 18.07.1977 Winners of PVC-2: CHM Piru Singh, PVC (1916 - 1948), 6th Bn, The Rajputana Rifles. 18 20.10.1977 Battle Honours of The Madras Sappers Head Quarters Madras Engineer Group & Centre 19 21.11.1977 The Parachute Regiment 20 06.02.1978 Winners of PVC-3: Nk. -

203Rd Anniversary of the Bhima-Koregaon Battle

203rd Anniversary of the Bhima-Koregaon Battle drishtiias.com/printpdf/203rd-anniversary-of-the-bhima-koregaon-battle Why in News The victory pillar (also known as Ranstambh or Jaystambh) in Bhima-Koregaon village (Pune district of Maharashtra) celebrated the 203rd anniversary of the Bhima- Koregaon battle of 1818 on 1st January, 2021. In 2018, incidents of violent clashes between Dalit and Maratha groups were registered during the celebration of the 200th anniversary of the Bhima-Koregaon battle. Key Points 1/2 Historical Background: A battle was fought in Bhima Koregaon between the Peshwa forces and the British on 1st January, 1818. The British army, which comprised mainly of Dalit soldiers, fought the upper caste-dominated Peshwa army. The British troops defeated the Peshwa army. Peshwa Bajirao II had insulted the Mahar community and terminated them from the service of his army. This caused them to side with the English against the Peshwa’s numerically superior army. Mahar, caste-cluster, or group of many endogamous castes, living chiefly in Maharashtra state and in adjoining states. They mostly speak Marathi, the official language of Maharashtra. They are officially designated Scheduled Castes. The defeat of Peshwa army was considered to be a victory against caste-based discrimination and oppression. It was one of the last battles of the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817-18), which ended the Peshwa domination. Babasaheb Ambedkar’s visit to the site on 1st January, 1927, revitalised the memory of the battle for the Dalit community, making it a rallying point and an assertion of pride. The Victory Pillar Memorial: It was erected by the British in Perne village in the district for the soldiers killed in the Koregaon Bhima battle. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

Question Bank Mcqs TYBA Political Science Semester V 2019-20 Paper-6 Politics of Modern Maharashtra

Question Bank MCQs TYBA Political Science Semester V 2019-20 Paper-6 Politics of Modern Maharashtra 1. Who founded the SNDT University for women in 1916? a) M.G.Ranade b) Dhondo Keshav Karve c) Gopal Krishna Gokhale d) Bal Gangadhar Tilak 2. Who was associated with the Satyashodhak Samaj? a) Sri Narayan Guru b) Jyotirao Phule c) Dr. B. R. Ambedkar d) E.V. Ramaswamy Naicker 3. When was the Indian National Congress established? a) 1875 b) 1885 c) 1905 d) 1947 4. Which Marathi newspaper was published by Bal Gangadhar Tilak a) Kesari b) Poona Vaibhav c) Sakal d) Darpan 5. Which day is celebrated as the Maharashtra Day? a) 12th January b) 14th April c) 1st May d) 2nd October 6. Under whose leadership Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti was founded? a) Keshavrao Jedhe b) S. A. Sange c) Uddhavrao Patil d) Narayan Ganesh Gore 7. When did the Bilingual Bombay State come into existence? a) 1960 b) 1962 c) 1956 d) 1947 8. Which one of the following city comes under Vidarbha region? a) Nagpur b) Poona c) Aurangabad d) Raigad 9. Till 1948 Marathwada region was part of which of the following? a) Central Province and Berar b) Bombay State c) Hyderabad State d) Junagad 10. Dandekar Committee dealt with which of the following issues? a) Maharashtra’s Educational policy b) The problem of imbalance in development between different regions of Maharashtra c) Trade and commerce policy of Maharashtra d) Agricultural policy 11. Which one of the following is known as the financial capital of India? a) Pune b) Mumbai c) Nagpur d) Aurangabad 12. -

“Re-Rigging” the Vedas: Examining the Effects of Changing Education and Purity Standards and Political Influence on the Contemporary Hindu Priesthood

“Re-Rigging” the Vedas: Examining the Effects of Changing Education and Purity Standards and Political Influence on the Contemporary Hindu Priesthood Christine Shanaberger Religious Studies RST 490 David McMahan, advisor Submitted: May 4, 2006 Graduated: May 13, 2006 1 Introduction In the academic study of religion, we are often given impressions about a tradition that are textually accurate, but do not directly correspond with its practice amongst its devotees. Hinduism is one such tradition where scholarly work has been predominately textual and quite removed from practices “on the ground.” While most scholars recognize that many indigenous Hindu practices do not conform to the Brahmanical standards described in ancient Hindu texts, there has only recently been a movement to study the “popular,” non-Brahmanical traditions, let alone to look at the Brahmanical practice and its variance with ancient conventions. I have personally experienced this inconsistency between textual and popular Hinduism. After spending a semester in India, I quickly realized that my background in the study of Hinduism was, indeed, merely a background. I found myself re-learning aspects of the tradition and theology that I thought I had already understood and redefining the meaning of many practices as I learned of their practical application. Most importantly, I discovered that Hindu practices and beliefs are so diverse that I could never anticipate who would believe or practice in what way. I met many “modernized” Indians who both ignored and retained many orthodox elements of their traditions, priests who were unaware of even the most basic elements of Hindu mythology, and devotees who had no qualms engaging in both orthodox Brahmin and quite unorthodox non-Brahmin religious practices. -

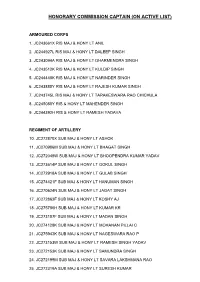

Honorary Commission Captain (On Active List)

HONORARY COMMISSION CAPTAIN (ON ACTIVE LIST) ARMOURED CORPS 1. JC243661X RIS MAJ & HONY LT ANIL 2. JC244927L RIS MAJ & HONY LT DALEEP SINGH 3. JC243094A RIS MAJ & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH 4. JC243512K RIS MAJ & HONY LT KULDIP SINGH 5. JC244448K RIS MAJ & HONY LT NARINDER SINGH 6. JC243880Y RIS MAJ & HONY LT RAJESH KUMAR SINGH 7. JC243745L RIS MAJ & HONY LT TARAKESWARA RAO CHICHULA 8. JC245080Y RIS & HONY LT MAHENDER SINGH 9. JC244392H RIS & HONY LT RAMESH YADAVA REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY 10. JC272870X SUB MAJ & HONY LT ASHOK 11. JC270906M SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHAGAT SINGH 12. JC272049W SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHOOPENDRA KUMAR YADAV 13. JC273614P SUB MAJ & HONY LT GOKUL SINGH 14. JC272918A SUB MAJ & HONY LT GULAB SINGH 15. JC274421F SUB MAJ & HONY LT HANUMAN SINGH 16. JC270624N SUB MAJ & HONY LT JAGAT SINGH 17. JC272863F SUB MAJ & HONY LT KOSHY AJ 18. JC275786H SUB MAJ & HONY LT KUMAR KR 19. JC273107F SUB MAJ & HONY LT MADAN SINGH 20. JC274128K SUB MAJ & HONY LT MOHANAN PILLAI C 21. JC275943K SUB MAJ & HONY LT NAGESWARA RAO P 22. JC273153W SUB MAJ & HONY LT RAMESH SINGH YADAV 23. JC272153K SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAMUNDRA SINGH 24. JC272199M SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAVARA LAKSHMANA RAO 25. JC272319A SUB MAJ & HONY LT SURESH KUMAR 26. JC273919P SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 27. JC271942K SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 28. JC279081N SUB & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH RATHORE 29. JC277689K SUB & HONY LT KAMBALA SREENIVASULU 30. JC277386P SUB & HONY LT PURUSHOTTAM PANDEY 31. JC279539M SUB & HONY LT RAMESH KUMAR SUBUDHI 32. -

![JUDGMENT [Per Ranjit More, J.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5744/judgment-per-ranjit-more-j-575744.webp)

JUDGMENT [Per Ranjit More, J.]

1 Marata(J) final.doc IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION PUBLIC INTEREST LITIGATION NO. 175 OF 2018 Dr. Jishri Laxmnarao Patil, ] Member the Indian Constitutionalist ] Council, Age 39 years, Occu : Advocate, ] Having oce at C/o 109/18, ] Esplanade Mansion, M. G. Road, ] Mumbai 400023. ...Petitioner ]..Petitioner. Versus 1. The Chief Minister ] of State of Maharashtra, Mantralaya, ] Mumbai – 400 032. ] ] 2. the Chief Secretary, ] State of Maharashtra, Mantralaya, ] Mumbai – 400 032. ]..Respondents. WITH CIVIL APPLICATION NO. 6 OF 2019 IN PUBLIC INTEREST LITIGATION NO. 175 OF 2018 Gawande Sachin Sominath. ] Age 32 years, Occ : Social Activist, ] R/o Plot No. 64, Lane No. 7, Gajanan Nagar ] Garkheda Parisar, Aurangabad. ]..Applicant. IN THE MATTER BETWEEN Dr. Jishri Laxmnarao Patil, ] Member the Indian Constitutionalist ] Council, Age 39 years, Occu : Advocate, ] Having oce at C/o 109/18, ] Esplanade Mansion, M. G. Road, ] Mumbai 400023. ]..Petitioner. patil-sachin. ::: Uploaded on - 08/07/2019 ::: Downloaded on - 15/07/2019 20:18:51 ::: 2 Marata(J) final.doc Versus 1. The Chief Minister ] of State of Maharashtra, Mantralaya, ] Mumbai – 400 032. ] ] 2. The Chief Secretary, ] State of Maharashtra, Mantralaya, ] Mumbai – 400 032. ] ] 3. Anandrao S. Kate, ] Address at Shoop no. 12 ] Building no. 26, A, ] Lullbhai Compound, ] mumbai-400043 ] ] 4. Akhil Bhartiya Maratha ] Mahasangh, ] Reg. No. 669/A, ] Though. Dilip B Jagatap ] ts Oce at.5, Navalkar ] Lane Prarthana Samaj ] Girgaon, Mumbai-04 ] ] 5. Vilas A. Sudrik, ] 265, “Shri Ganesh Chalwal, ] Juie Aunty Compound ] Santosh Nagar, Gaorgaon (E) ] Mumbai-64 ] ] 6. Ashok Patil ] A/G/001, Mehdoot Co-op Society, ] Mahada Vasahat Thane, 4000606 ] ] 7. -

![Poona Sarvajanik Sabha Founded - [April 2, 1870] This Day in History](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2228/poona-sarvajanik-sabha-founded-april-2-1870-this-day-in-history-712228.webp)

Poona Sarvajanik Sabha Founded - [April 2, 1870] This Day in History

Poona Sarvajanik Sabha Founded - [April 2, 1870] This Day in History On 2nd April 1870, Poona Sarvajanik Sabha was founded. In this edition of This Day in History, you can read about the important socio-political organisation Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, an early platform where educated Indians expressed their opinions and demands from the British government. This is a part of UPSC Syllabus on history. Aspirants would find this article very helpful while preparing for the IAS Exam. Background of Poona Sarvajanik Sabha for UPSC 1. The Poona Sarvajanik Sabha was established on 2 April 1870 at Poona originally because of the discontent of the people over the running of a local temple. 2. The Deccan Association formed in 1850 and the Poona Association formed in 1867 had become defunct within a few years and the western educated residents of Poona felt the need for a modern socio-political organisation. 3. Mahadev Govind Ranade, an eminent lawyer and scholar from the Bombay Presidency was also a keen social reformer. He played a major part in the formation of the Sarvajanik Sabha. 4. The other key members who helped in its formation were Bhawanrao Shriniwasrao Pant Pratinidhi (ruler of the Aundh State who was also the organisation’s first president), Ganesh Vasudeo Joshi and S H Chiplunkar. 5. Other important members of the Sabha included M M Kunte, Vishnu M Bhide, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Gopal Hari Deshmukh. The members were mostly from the educated middle class of society and comprised of lawyers, inamdars, pensioners, pleaders, teachers, journalists and government servants in the judicial and education departments. -

14. Formation of State of Maharashtra

14. Formation of State of Maharashtra After India gained independence, there was demand on large scale for the reconstruction of states on linguistic basis. In Maharashtra also the demand for state of Marathi speaking people led to ‘Samyukta Maharashtra Movement’ from 1946 onwards. Through various changing circumstances the movement progressed and finally on 1 May 1960 the state of Maharashtra came to be formed. Background : From the beginning of 20th century, many scholars had begun to express the thoughts on unification of Marathi speaking people. In 1911, the British Government had to suspend the partition of Bengal. On this background, N.C.Kelkar wrote that ‘the entire Marathi speaking poulation should be under one dominion’. In 1915, Lokmanya Tilak had demanded the reconstruction of a state based on language. But during that period the issue of independence of India was more important, hence this issue remained aside. On 12 May 1946, in the Sahitya Sammelan at Belgaon, an important resolution regarding Samyukta Maharashtra was passed. Samyukta Maharashtra Parishad : On 28 July, ‘Maharashtra Ekikaran Parishad’ was called at Mumbai. Shankarrao Dev was its president. It passed a resolution that all Marathi speaking regions should be included in one state. This should also include Marathi speaking regions of Mumbai, Central provinces as well as Marathwada and Gomantak. Dar Commission : On 17 June 1947, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, the President of Constituent Assembly established the ‘Dar Commission’ under the chairmanship of Justice S.K.Dar, for forming linguistic provinces. On 10 December 1948, the report of Dar Commission was published but the issue remained unsolved. -

India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures

India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures by Ranjit Deshmukh A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Energy and Resources in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Duncan Callaway, Chair Professor Severin Borenstein Dr. Michael Milligan Professor Daniel M. Kammen Professor Meredith Fowlie Fall 2016 India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures Copyright 2016 by Ranjit Deshmukh 1 Abstract India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures by Ranjit Deshmukh Doctor of Philosophy in Energy and Resources University of California, Berkeley Professor Duncan Callaway, Chair Decarbonizing its electricity sector through ambitious targets for wind and solar is India's major strategy for mitigating its rapidly growing carbon emissions. In this dissertation, I explore the economic, social, and environmental impacts of wind and solar generation on India's future low-carbon electricity system, and strategies to mitigate those impacts. In the first part, I apply the Multi-criteria Analysis for Planning Renewable Energy (MapRE) approach to identify and comprehensively value high-quality wind, solar photovoltaic, and concentrated solar power resources across India in order to support multi-criteria prioritiza- tion of development areas through planning processes. In the second part, I use high spatial and temporal resolution models to simulate operations of different electricity system futures for India. In analyzing India's 2022 system, I find that the targets of 100 GW solar and 60 GW wind set by the Government of India that are likely to generate 22% of total annual electricity, can be integrated with very small curtailment (approximately 1%). -

Ambedkar Times September, 2014 Layout 1

Editor-in-Chief: Prem Kumar Chumber Contact: 001-916-947-8920 Fax: 916-238-1393 E-mail: [email protected] Editors: Takshila & Kabir Chumber VOL- 6 ISSUE- 12-13 September, 2014 www.ambedkartimes.com www.ambedkartimes.org Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, Poona Pact and the Current Situation Efforts to purchase Dr Ambedkar former Prem K. Chumber (Editor-in Chief) www.ambedkartimes.com Residence in London for an Ambedkar Memorial Babasaheb Dr. B. R. Ambedkar devoted his entire life pounds to purchase the property. proposed memorial will be a cul- for the emancipation and empowerment of the London (Ambedkar Times "I am delighted that the Govern- tural and educational centre that Scheduled Castes of India who for centuries have News Bureau)- Efforts are being ment of Maharashtra has sup- generations of Indians in the UK been compelled to live in deplorable situations. He made to convert the former Lon- ported the FABO, UK's initiative and visitors interested or inspired tried different ways for this noble cause while set- don residence of Dr B.R. Ambed- to purchase the house where Dr by Dr Ambedkar’s key roles in ting the goal of annihilation of caste. First, he did kar into an Ambedkar memorial. Ambedkar lodged while he was furthering social justice, human his best to improve upon the situations through re- He lived at 10 King Henrys Road studying at the London School of rights and equal treatment issues forms within Hinduism. But soon, he realized that London in 1921-22 during his can visit. The bedrooms would reforms within Hinduism will not work for the anni- higher studies in the London be ideal for some students from hilation of caste because without caste the whole School of Economics.