INDIA by Prachi Deshmukh Odhekar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures

India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures by Ranjit Deshmukh A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Energy and Resources in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Duncan Callaway, Chair Professor Severin Borenstein Dr. Michael Milligan Professor Daniel M. Kammen Professor Meredith Fowlie Fall 2016 India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures Copyright 2016 by Ranjit Deshmukh 1 Abstract India's Low Carbon Electricity Futures by Ranjit Deshmukh Doctor of Philosophy in Energy and Resources University of California, Berkeley Professor Duncan Callaway, Chair Decarbonizing its electricity sector through ambitious targets for wind and solar is India's major strategy for mitigating its rapidly growing carbon emissions. In this dissertation, I explore the economic, social, and environmental impacts of wind and solar generation on India's future low-carbon electricity system, and strategies to mitigate those impacts. In the first part, I apply the Multi-criteria Analysis for Planning Renewable Energy (MapRE) approach to identify and comprehensively value high-quality wind, solar photovoltaic, and concentrated solar power resources across India in order to support multi-criteria prioritiza- tion of development areas through planning processes. In the second part, I use high spatial and temporal resolution models to simulate operations of different electricity system futures for India. In analyzing India's 2022 system, I find that the targets of 100 GW solar and 60 GW wind set by the Government of India that are likely to generate 22% of total annual electricity, can be integrated with very small curtailment (approximately 1%). -

NASCENT NATIONALISM in the PRINCELY STATES While Political

33 Chapter II NASCENT NATIONALISM IN THE PRINCELY STATES While political questions, the growth of polity in British India and its ripple effect in the Princely States vexed the Crown of England and the Government of India, the developments in education, communication and telegraphs played the well known role of unifying India in a manner hitherto unknown. It was during the viceroyalty of Lord Duffrine that the Indian National Congress was formed under the patronage of A.O. Hume. In 1885, and throughout the second half of the 19th Century, there existed in Calcutta and other metropolitan towns in India a small but energetic group of non-official Britons-journalists, teachers, lawyers, missionaries, planters and traders - nicknamed ’interlopers’ by the Company’s servants who cordially detested them. The interlopers brought their politics into India and behaved almost exactly as they would have done in England. They published their rival newspapers, founded schools and missions and 34 organised clubs, associations and societies of all sorts. They kept a close watch on the doings of the Company’s officials. Whenever their interests were adversely affected by the decisions of the government, they raised a hue and cry in the press, organised protest meetings sent in petitions, waited in deputations and even tried to influence Parliament and public opinion in England and who by their percept and example they taught their Indian fellow subjects the art of constitutional agitation.' In fact, the seminal role of the development of the press in effective unification within the country and in the spread of the ideas of democracy and freedom that transcended barriers which separated the provinces from the Princely India is not too obvious. -

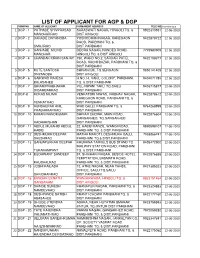

List of Applicant for Agp &

LIST OF APPLICANT FOR AGP & DGP FORM NO NAME OF ALLICANT PARMANENT ADDRESS TELE NO Interview date 1 DGP - 1 PATHADE SHIVPRASAD SARASWATI NAGAR, HINGOLI TQ. & 9922310551 12-06-2019 MANOHARRAO DIST.HINGOLI 2 DGP - 2 DARADE DNYANOBA YOSHODHAN NAGAR, KAREGAON 9422878722 12-06-2019 RAOD, PARBHANI TQ. & UMAJIRAO DIST.PARBHANI 3 DGP - 3 GANJARE MILIND DEORA NAGAR, NANDED ROAD, 7775980909 12-06-2019 MANOHAR HINGOLI TQ. & DIST.HINGOLI 4 DGP - 4 CHANDAK KIRAN SANJAY 150, WARD NO.2, SARDAR PATEL 9422108377 12-06-2019 ROAD, KACHI BAZAR, PARBHANI TQ. & DIST.PARBHANI 5 DGP - 5 KUTE SANTOSH SHIVANI BK, TQ.SENGAON 9850141405 12-06-2019 DNYANOBA DIST.HINGOLI 6 DGP - 6 GAIKWAD RAJESH H.NO.14, VAKIL COLONY, PARBHANI. 9404071783 12-06-2019 BALASAHEB TQ. & DIST.PARBHANI 7 DGP - 7 GIRAM PRABHAKAR VILL-NIPANI TAKLI TQ.SAILU 9403715877 12-06-2019 DIGAMBARRAO DIST.PARBHANI 8 DGP-8 KOKAD NILIMA VENKATDRI NIWAS, VAIBHAV NAGAR, 9422878612 12-06-2019 KAREGAON ROAD, PARBHANI TQ. & VENKATRAO DIST.PARBHANI 9 DGP - 9 AUNDHEKAR ANIL WAD GALLI, PARBHANI TQ. & 9764268999 12-06-2019 PRABHAKARRAO DIST.PARBHANI 10 DGP - 10 KAKANI NANDKUMAR SHIVAJI CHOWK, MAIN ROAD, 9422876604 12-06-2019 GANGAKHED, TQ.GANGAKHED RADHAKISHAN DIST.PARBHANI 11 DGP - 11 ABDUL MUJAHID ABDUL 22, HABIB MANZIL, WANGI ROAD, 9890598107 12-06-2019 HABIB PARBHANI TQ. & DIST.PARBHANI 12 DGP - 12 DESHMUKH DEEPAK MATHA MAROTI, DESHMUKH GALLI, 7038866741 12-06-2019 SHESHRAO PARBHANI TQ.& DIST.PARBHANI 13 DGP - 13 GANJAPURKAR DEEPAK KHURANA TARVELS BUS STAND TO 9405472900 12-06-2019 RAILWAY STATION ROAD, PARBHANI TUKARAMPANT TQ. & DIST.PARBHANI 14 DGP - 14 BUDHWANT SANDEEP 57, SHRIHARI NAGAR, BESIDE HOTEL 9422876655 12-06-2019 TEMPTATION, BASMATH ROAD, KHUSHALRAO PARBHANI TQ. -

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798. -

The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India

chapter 1 Caste Radicalism and the Making of a New Political Subject In colonial India, print capitalism facilitated the rise of multiple, dis- tinctive vernacular publics. Typically associated with urbanization and middle-class formation, this new public sphere was given material form through the consumption and circulation of print media, and character- ized by vigorous debate over social ideology and religio-cultural prac- tices. Studies examining the roots of nationalist mobilization have argued that these colonial publics politicized daily life even as they hardened cleavages along fault lines of gender, caste, and religious identity.1 In west- ern India, the Marathi-language public sphere enabled an innovative, rad- ical form of caste critique whose greatest initial success was in rural areas, where it created novel alliances between peasant protest and anticaste thought.2 The Marathi non-Brahmin public sphere was distinguished by a cri- tique of caste hegemony and the ritual and temporal power of the Brah- min. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, Jotirao Phule’s writings against Brahminism utilized forms of speech and rhetorical styles asso- ciated with the rustic language of peasants but infused them with demands for human rights and social equality that bore the influence of noncon- formist Christianity to produce a unique discourse of caste radicalism.3 Phule’s political activities, like those of the Satyashodak Samaj (Truth Seeking Society) he established in 1873, showed keen awareness of trans- formations wrought by colonial modernity, not least of which was the “new” Brahmin, a product of the colonial bureaucracy. Like his anticaste, 39 40 Emancipation non-Brahmin compatriots in the Tamil country, Phule asserted that per- manent war between Brahmin and non-Brahmin defined the historical process. -

The First Anglo-Maratha War Third Phase (1779-1783

THE FIRST ANGLO-MARATHA WAR THIRD PHASE (1779-1783) Chapter VII - THE SsiGOND BORGHAT BXPSDITION (1781) For geographiciO., rtfargncts^ » •« Map Nog. Xb W 1 9 . attached at the beginning of this chapter, bttween pp. 251«2^2. nlso see Mao No. 12. attached at the beginning of chapter V. between p p . 15^-155. M A P NO. 16 SECOND BORGHAT EXPEDITION (l78l)- ^UTES OF march of the TWO ARMIES DlSPOSlT»OK OF THE MARATHA TROOPS CAMPIN& GROUND ROUTE OF THE BRITISH ARMy UP TO KHANPALA ^^^ESCARPMENT [ h ^ = HARJPANnr PHADKE i RBj: PARASHURAMBHAU [t h I- TUK0J{ HOLKAR p a t w a r d h a h M AP NO. 17. M A I N C A M P euMMtT or BORGHAT SRITJSH THE MARATMA6 POaiTtONS a d v a m c e g u a r d GODDARD'S MAIN .OP THE MARATMAS C PArWARDHAN , pwaDke CAMP p a n a s c a h d — wCL»tAR JCtHl ^ KWANDALAv h o r o n h a 3 (SOO FT ■V a 6ovE « E A U E V ' E U •\ REAR BASE OF GODDARD aeCOND BOFX3HAT EXPEOm ON C17ai) SECTION F IR S T T A C T I C A L PL>swN O F T H E M A R A T H A S 9 c /M .e : i^s 2HICKS KHOPOLI QFRONTAU ATTACK O N THE ENEMY- FE8-I7«t ;> V4te~lGHT IN FEET / eUMKlT CF 5CRGHAT CGCDDARD'S BAJIPAHT CAMP) ✓ HAf?lPANT n P^IADK E ' w - MSU > I. lADVANr.e: > «,-t-20CXJ' ^ sl mp o ! ) / / /S»» - « *A i ■ -w- ^UART> OF THE MARATHAe Tu k .0J! PO&ITtOKJS < k A R L £ HOiKAfff MAtM CAN-P <0R0nH4' r C F T M E A N M A R A T H A ^ . -

4. Maharashtra Before the Times of Shivaji Maharaj

The Coordination Committee formed by GR No. Abhyas - 2116/(Pra.Kra.43/16) SD - 4 Dated 25.4.2016 has given approval to prescribe this textbook in its meeting held on 3.3.2017 HISTORY AND CIVICS STANDARD SEVEN Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, Pune - 411 004. First Edition : 2017 © Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, Reprint : September 2020 Pune - 411 004. The Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research reserves all rights relating to the book. No part of this book should be reproduced without the written permission of the Director, Maharashtra State Bureau of Textbook Production and Curriculum Research, ‘Balbharati’, Senapati Bapat Marg, Pune 411004. History Subject Committee : Cartographer : Dr Sadanand More, Chairman Shri. Ravikiran Jadhav Shri. Mohan Shete, Member Coordination : Shri. Pandurang Balkawade, Member Mogal Jadhav Dr Abhiram Dixit, Member Special Officer, History and Civics Shri. Bapusaheb Shinde, Member Varsha Sarode Shri. Balkrishna Chopde, Member Subject Assistant, History and Civics Shri. Prashant Sarudkar, Member Shri. Mogal Jadhav, Member-Secretary Translation : Shri. Aniruddha Chitnis Civics Subject Committee : Shri. Sushrut Kulkarni Dr Shrikant Paranjape, Chairman Smt. Aarti Khatu Prof. Sadhana Kulkarni, Member Scrutiny : Dr Mohan Kashikar, Member Dr Ganesh Raut Shri. Vaijnath Kale, Member Prof. Sadhana Kulkarni Shri. Mogal Jadhav, Member-Secretary Coordination : Dhanavanti Hardikar History and Civics Study Group : Academic Secretary for Languages Shri. Rahul Prabhu Dr Raosaheb Shelke Shri. Sanjay Vazarekar Shri. Mariba Chandanshive Santosh J. Pawar Assistant Special Officer, English Shri. Subhash Rathod Shri. Santosh Shinde Smt Sunita Dalvi Dr Satish Chaple Typesetting : Dr Shivani Limaye Shri. -

Linguistic States and Formation of Samyukta Maharashtra

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 12, Ver. IV (Dec. 2015) PP 80-82 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Linguistic States and Formation of Samyukta Maharashtra Ashish Nareshrao Thakare, B. D. College of Engineering, Sevagram Abstract: "The language and culture of an area have an undoubted importance as they represent a pattern of living which is common in that area." - Resolution of the Government of India relating to the State Reorganization Commission, 1953 According to historical records, during the British rule, India was divided into about “600 princely states and provinces”. Language is a major aspect of national consolidation and integration. The reorganization of the states based on the language came to the fore almost immediately after independence. Samyukta Maharashtra Movement was the most powerful movement after independence. The movement received active support from Maharashtrian people. The inclusion of Bombay in the Maharashtra state is considered as the victory of the movement. Marathi Newspapers “Navyug”, Maratha, Samyukta Maharashtra Patrika, Prabhat, Belgaon Samachar, Navakal etc. played a key role to make this movement more mass base. “Maratha” was considered as the mouthpiece of the movement. Marathi Newspapers spearheaded the demand for the creation of a separate Marathi-speaking state with the city of Bombay as its capital. Keywords: movement, Language, spearheaded. I. Introduction: The rise and growth of the Samyukta Maharashtra movement must be studied not merely in the general context of the country-wide agitation for linguistic States but also in the particular context of the society and politics in Maharashtra Language is closely related to culture and therefore to the customs of people. -

11.04 Hrs LIST of MEMBERS ELECTED to LOK SABHA Sl. No

Title: A list of Members elected to 14th Lok Sabha was laid on the Table of the House. 11.04 hrs LIST OF MEMBERS ELECTED TO LOK SABHA MR. SPEAKER: Now I would request the Secretary-General to lay on the Table a list (Hindi and English versions), containing the names of the Members elected to the Fourteenth Lok Sabha at the General Elections of 2004, submitted to the Speaker by the Election Commission of India. SECRETARY-GENERAL: Sir, I beg to lay on the Table a List* (Hindi and English versions), containing the names of Members elected to the Fourteenth Lok Sabha at the General Elections of 2004, submitted to the Speaker by the Election Commission of India. List of Members Elected to the 14th Lok Sabha. * Also placed in the Library. See No. L.T. /2004 SCHEDULE Sl. No. and Name of Name of the Party Affiliation Parliamentary Constituency Elected Member (if any) 1. ANDHRA PRADESH 1. SRIKAKULAM YERRANNAIDU KINJARAPUR TELUGU DESAM 2. PARVATHIPURAM(ST) KISHORE CHANDRA INDIAN NATIONAL SURYANARAYANA DEO CONGRESS VYRICHERLA 3. BOBBILI KONDAPALLIPYDITHALLI TELEGU DESAM NAIDU 4. VISAKHAPATNAM JANARDHANA REDDY INDIAN NATIONAL NEDURUMALLI CONGRESS 5. BHADRACHALAM(ST) MIDIYAM BABU RAO COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MARXIST) 6. ANAKAPALLI CHALAPATHIRAO PAPPALA TELUGU DESAM 7. KAKINADA MALLIPUDI MANGAPATI INDIAN NATIONAL PALLAM RAJU CONGRESS 8. RAJAHMUNDRY ARUNA KUMAR VUNDAVALLI INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 9. AMALAPURAM (SC) G.V. HARSHA KUMAR INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 10. NARASAPUR CHEGONDI VENKATA INDIAN NATIONAL HARIRAMA JOGAIAH CONGRESS 11. ELURU KAVURU SAMBA SIVA RAO INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 12. MACHILIPATNAM BADIGA RAMAKRISHNA INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 13. VIJYAWADA RAJAGOPAL GAGADAPATI INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 14. -

BA Semester VI- Maratha History 1707-1818 AD (HISKB 602) Dr. Mukesh

BA Semester VI- Maratha History 1707-1818 AD (HISKB 602) Dr. Mukesh Kumar (Department of History) KMC Language University Lucknow, U.P.-226013 UNIT-I Chhatrapati Shahu- Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj also known as Rajarshi Shahu was considered a true democrat and social reformer. First Maharaja of the princely state of Kolhapur, he was an invaluable gem in the history of Maharashtra. Greatly influenced by the contributions of social reformer Jyotiba Phule, Shahu Maharaj was an ideal leader and able ruler who was associated with many progressive and path breaking activities during his rule. From his coronation in 1894 till his demise in 1922, he worked tirelessly for the cause of the lower caste subjects in his state. Primary education to all regardless of caste and creed was one of his most significant priorities. He was born Yeshwantrao in the Ghatge family in Kagal village of the Kolhapur district as Yeshwantrao Ghatge to Jaisingrao and Radhabai in June 26, 1874. Jaisingrao Ghatge was the village chief, while his wife Radhabhai hailed from the royal family of Mudhol. Young Yeshwantrao lost his mother when he was only three. His education was supervised by his father till he was 10-year-old. In that year, he was adopted by Queen Anandibai, widow of Kingh Shivaji IV, of the princely state of Kolhapur. Although the adoption rules of the time dictated that the child must have Bhosale dynasty blood in his vein, Yeshwantrao’s family background presented a unique case. He completed his formal education at the Rajkumar College in Rajkot and took lessons of administrative affairs from Sir Stuart Fraser, a representative of the Indian Civil Services. -

Responsible Person List

Responsible Person List S Lic No. Valid Valid Upto Firm Name Responsible Person Residential Address Office Address Mobile No. From Name 1 LAFD21010001 17/05/2013 16/05/2016 Jai Hanuman Mahesh Vijaykumar At Post Pimpalgaon (sm) At Post Pimpalgaon (sm) 9673462967 Krushi Kendra More Taluka Dist Parbhani Taluka Dist Parbhani 22, HSC Village: Pimpalgaon Village: Pimpalgaon Sayyadmia, Taluka: Sayyadmia, Taluka: Parbhani, Dist: Parbhani, Parbhani, Dist: Parbhani, State: Maharashtra State: Maharashtra 2 LAFD21010002 17/05/2013 16/05/2016 Ganesh Krushi Dilip Ganeshrao At Post Zari Taluka Dist At Post Zari Taluka Dist 9405117744 Kendra Ragade Parbhani Village: Za, Parbhani Village: Za, 45, BA Taluka: Parbhani, Dist: Taluka: Parbhani, Dist: Parbhani, State: Parbhani, State: Maharashtra Maharashtra 3 LAFD21010003 20/05/2016 19/05/2019 Vitthal Traders Pralhad Vishwanath House Na 579 At Pimpari House Na 579 At Pimpari 7588018722 Awakale Deshmukh Taluka Dist Deshmukh Taluka Dist 33, SSC Parbhani Village: Pimpari Parbhani Village: Pimpari Deshmukh, Taluka: Deshmukh, Taluka: Parbhani, Dist: Parbhani, Parbhani, Dist: Parbhani, State: Maharashtra State: Maharashtra 4 LAFD21010004 20/05/2013 19/05/2016 Jagdamba Mohan Ramrao Gavane Chowk Parbhani Gavane Chowk Parbhani 9767191445 Krushi Kendra Lonikar Village: Parbhani (m Cl), Village: Parbhani (m Cl), 30, HSC Taluka: Parbhani, Dist: Taluka: Parbhani, Dist: Parbhani, State: Parbhani, State: Maharashtra Maharashtra 5 LAFD21010005 22/05/2016 21/05/2019 Sai Seeds And Subhash Manikrao At Post Takli Kumbhakarna At Post Takli Kumbhakarna 9766663738 Fartilizer Samale Taluka Dist Parbhani Taluka Dist Parbhani 25, D ED Village: Takli Village: Takli Kumbhakarna, Taluka: Kumbhakarna, Taluka: Parbhani, Dist: Parbhani, Parbhani, Dist: Parbhani, State: Maharashtra State: Maharashtra 1 / 341 S Lic No.