History Paper - I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Question Bank Mcqs TYBA Political Science Semester V 2019-20 Paper-6 Politics of Modern Maharashtra

Question Bank MCQs TYBA Political Science Semester V 2019-20 Paper-6 Politics of Modern Maharashtra 1. Who founded the SNDT University for women in 1916? a) M.G.Ranade b) Dhondo Keshav Karve c) Gopal Krishna Gokhale d) Bal Gangadhar Tilak 2. Who was associated with the Satyashodhak Samaj? a) Sri Narayan Guru b) Jyotirao Phule c) Dr. B. R. Ambedkar d) E.V. Ramaswamy Naicker 3. When was the Indian National Congress established? a) 1875 b) 1885 c) 1905 d) 1947 4. Which Marathi newspaper was published by Bal Gangadhar Tilak a) Kesari b) Poona Vaibhav c) Sakal d) Darpan 5. Which day is celebrated as the Maharashtra Day? a) 12th January b) 14th April c) 1st May d) 2nd October 6. Under whose leadership Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti was founded? a) Keshavrao Jedhe b) S. A. Sange c) Uddhavrao Patil d) Narayan Ganesh Gore 7. When did the Bilingual Bombay State come into existence? a) 1960 b) 1962 c) 1956 d) 1947 8. Which one of the following city comes under Vidarbha region? a) Nagpur b) Poona c) Aurangabad d) Raigad 9. Till 1948 Marathwada region was part of which of the following? a) Central Province and Berar b) Bombay State c) Hyderabad State d) Junagad 10. Dandekar Committee dealt with which of the following issues? a) Maharashtra’s Educational policy b) The problem of imbalance in development between different regions of Maharashtra c) Trade and commerce policy of Maharashtra d) Agricultural policy 11. Which one of the following is known as the financial capital of India? a) Pune b) Mumbai c) Nagpur d) Aurangabad 12. -

![Poona Sarvajanik Sabha Founded - [April 2, 1870] This Day in History](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2228/poona-sarvajanik-sabha-founded-april-2-1870-this-day-in-history-712228.webp)

Poona Sarvajanik Sabha Founded - [April 2, 1870] This Day in History

Poona Sarvajanik Sabha Founded - [April 2, 1870] This Day in History On 2nd April 1870, Poona Sarvajanik Sabha was founded. In this edition of This Day in History, you can read about the important socio-political organisation Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, an early platform where educated Indians expressed their opinions and demands from the British government. This is a part of UPSC Syllabus on history. Aspirants would find this article very helpful while preparing for the IAS Exam. Background of Poona Sarvajanik Sabha for UPSC 1. The Poona Sarvajanik Sabha was established on 2 April 1870 at Poona originally because of the discontent of the people over the running of a local temple. 2. The Deccan Association formed in 1850 and the Poona Association formed in 1867 had become defunct within a few years and the western educated residents of Poona felt the need for a modern socio-political organisation. 3. Mahadev Govind Ranade, an eminent lawyer and scholar from the Bombay Presidency was also a keen social reformer. He played a major part in the formation of the Sarvajanik Sabha. 4. The other key members who helped in its formation were Bhawanrao Shriniwasrao Pant Pratinidhi (ruler of the Aundh State who was also the organisation’s first president), Ganesh Vasudeo Joshi and S H Chiplunkar. 5. Other important members of the Sabha included M M Kunte, Vishnu M Bhide, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Gopal Hari Deshmukh. The members were mostly from the educated middle class of society and comprised of lawyers, inamdars, pensioners, pleaders, teachers, journalists and government servants in the judicial and education departments. -

NASCENT NATIONALISM in the PRINCELY STATES While Political

33 Chapter II NASCENT NATIONALISM IN THE PRINCELY STATES While political questions, the growth of polity in British India and its ripple effect in the Princely States vexed the Crown of England and the Government of India, the developments in education, communication and telegraphs played the well known role of unifying India in a manner hitherto unknown. It was during the viceroyalty of Lord Duffrine that the Indian National Congress was formed under the patronage of A.O. Hume. In 1885, and throughout the second half of the 19th Century, there existed in Calcutta and other metropolitan towns in India a small but energetic group of non-official Britons-journalists, teachers, lawyers, missionaries, planters and traders - nicknamed ’interlopers’ by the Company’s servants who cordially detested them. The interlopers brought their politics into India and behaved almost exactly as they would have done in England. They published their rival newspapers, founded schools and missions and 34 organised clubs, associations and societies of all sorts. They kept a close watch on the doings of the Company’s officials. Whenever their interests were adversely affected by the decisions of the government, they raised a hue and cry in the press, organised protest meetings sent in petitions, waited in deputations and even tried to influence Parliament and public opinion in England and who by their percept and example they taught their Indian fellow subjects the art of constitutional agitation.' In fact, the seminal role of the development of the press in effective unification within the country and in the spread of the ideas of democracy and freedom that transcended barriers which separated the provinces from the Princely India is not too obvious. -

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798. -

Impact Factor – 3.452 ISSN – 2348-7143

I N Impact Factor – 3.452 ISSN – 2348-7143 T INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH FELLOWS ASSOCIATION’S E R N RESEARCH JOURNEY Multidisciplinary International E-research Journal A T PEER REFREED & INDEXED JOURNAL I April 2018 O Special Issue – LVII [A] N LIFE & MISSION OF A BHARATRATNA DR. B.R. AMBEDKAR L Editorial Board of the Special Issue R Guest Editor: E Dr. Leena Pandhare Principal, Late Bindu Ramrao Deshmukh S Arts and Commerce Mahila Mahavidyalaya, E Nashik Road A Executive Editor: R Tejesh Beldar Assistant Professor, Dept. of English, C Late Bindu Ramrao Deshmukh Arts & H Commerce Mahila Mahavidyalaya, Nashik Road F Assistant Editors: E Bhaskar Narwate and Dr. Minal Barve Late Bindu Ramrao Deshmukh Arts and L Commerce Mahila Mahavidyalaya, L Nashik Road O Chief Editor: W Dr. Dhanraj T. Dhangar, Assist. Prof. (Marathi) S MGV‟s Arts and Commerce College, Yeola, Dist – Nashik [M.S.] INDIA A S This Journal is indexed in : S - University Grants Commission (UGC) List No. 40705 & 44117 O - Scientific Journal Impact Factor (SJIF) C - Cosmoc Impact Factor (CIF) - Global Impact Factor (GIF) I - Universal Impact Factor (UIF) A - International Impact Factor Services (IIFS) T - Indian Citation Index (ICI) - Dictionary of Research Journal Index (DRJI) I O N For Details Visit To : www.researchjourney.net SWATIDHAN PUBLICATIONS S ‘RESEARCH JOURNEY’ International Multidisciplinary E- Research Journal ISSN : Impact Factor - (CIF ) - 3.452, (SJIF) – 3.009, (GIF) –0.676 (2013) 2348-7143 Special Issue 57 [A]: Life & Mission of Bharatratna Dr. B. R. Ambedkar April UGC Approved No. 40705 & 44117 2018 Impact Factor – 3.452 ISSN – 2348-7143 INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH FELLOWS ASSOCIATION’S RESEARCH JOURNEY Multidisciplinary International E-Research Journal PEER REFREED & INDEXED JOURNAL April 2018 Special Issue – LVII [A] LIFE & MISSION OF BHARATRATNA DR. -

The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India

chapter 1 Caste Radicalism and the Making of a New Political Subject In colonial India, print capitalism facilitated the rise of multiple, dis- tinctive vernacular publics. Typically associated with urbanization and middle-class formation, this new public sphere was given material form through the consumption and circulation of print media, and character- ized by vigorous debate over social ideology and religio-cultural prac- tices. Studies examining the roots of nationalist mobilization have argued that these colonial publics politicized daily life even as they hardened cleavages along fault lines of gender, caste, and religious identity.1 In west- ern India, the Marathi-language public sphere enabled an innovative, rad- ical form of caste critique whose greatest initial success was in rural areas, where it created novel alliances between peasant protest and anticaste thought.2 The Marathi non-Brahmin public sphere was distinguished by a cri- tique of caste hegemony and the ritual and temporal power of the Brah- min. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, Jotirao Phule’s writings against Brahminism utilized forms of speech and rhetorical styles asso- ciated with the rustic language of peasants but infused them with demands for human rights and social equality that bore the influence of noncon- formist Christianity to produce a unique discourse of caste radicalism.3 Phule’s political activities, like those of the Satyashodak Samaj (Truth Seeking Society) he established in 1873, showed keen awareness of trans- formations wrought by colonial modernity, not least of which was the “new” Brahmin, a product of the colonial bureaucracy. Like his anticaste, 39 40 Emancipation non-Brahmin compatriots in the Tamil country, Phule asserted that per- manent war between Brahmin and non-Brahmin defined the historical process. -

Department of History

H.H. THE RAJAHA’S COLLEGE (AUTO), PUDUKKOTTAI - 622001 Department of History II MA HISTORY HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1947 C.E THIRD SEMESTER 18PHS7 MA HISTORY SEMESTER : III SUB CODE : 18PHS7 CORE COURSE : CCVIII CREDIT : 5 HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1947 C.E Objectives ● To understand the colonial hegemony in India ● To Inculcate the knowledge of solidarity shown by Indians against British government ● To know about the social reform sense through the historical process. ● To know the effect of the British rule in India. ● To know the educational developments and introduction of Press in India. ● To understand the industrial and agricultural bases set by the British for further developments UNIT – I Decline of Mughals and Establishment of British Rule in India Sources – Decline of Mughal Empire – Later Mughals – Rise of Marathas – Ascendancy under the Peshwas – Establishment of British Rule – the French and the British rivalry – Mysore – Marathas Confederacy – Punjab Sikhs – Afghans. UNIT – II Structure of British Raj upto 1857 Colonial Economy – Rein of Rural Economy – Industrial Development – Zamindari system – Ryotwari – Mahalwari system – Subsidiary Alliances – Policy on Non intervention – Doctrine of Lapse – 1857 Revolt – Re-organization in 1858. UNIT – III Social and cultural impact of colonial rule Social reforms – English Education – Press – Christian Missionaries – Communication – Public services – Viceroyalty – Canning to Curzon. ii UNIT – IV India towards Freedom Phase I 1885-1905 – Policy of mendicancy – Phase II 1905-1919 – Moderates – Extremists – terrorists – Home Rule Movement – Jallianwala Bagh – Phase III 1920- 1947 – Gandhian Era – Swaraj party – simon commission – Jinnah‘s 14 points – Partition – Independence. UNIT – V Constitutional Development from 1773 to 1947 Regulating Act of 1773 – Charter Acts – Queen Proclamation – Minto-Morley reforms – Montague Chelmsford reforms – govt. -

Modern History Test 06-02-2021 Time Allowed : Two Hours Maximum Marks : 200

Balalatha’s CSB IAS ACADEMY The Road Map to Mussoorie... TEST BOOKLET SERIES Test Code : MODERN HISTORY TEST 06-02-2021 TIME ALLOWED : TWO HOURS MAXIMUM MARKS : 200 1. IMMEDIATELY AFTER THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE EXAMINATION, YOU SHOULD CHECK THAT THIS TEST BOOKLET DOES NOT HAVE ANY UNPRINTED OR TORN OR MISSING PAGES OR ITEMS, ETC. IF SO, GET IT REPLACED BY A COMPLETE TEST BOOKLET. 2. Please note that it the candidate’s responsibility to encode and fill in the Roll Number and Test id carefully without any omission or discrepancy at the appropriate places in the OMR Answer Sheet. Any omission / discrepancy will render the Answer liable for rejection. 3. You have to enter your Roll Number on the Test Booklet in the Box provided alongside. 4. This Test Booklet contains 100 items (questions). Each item is printed in English. Each item comprises four responses (answers). You will select the response which you consider the best. In any case choose ONLY ONE response for each item. 5. You have mark, all your responses ONLY on the separate Answer Sheet provided. See directions in the Answer Sheet. 6. All items carry equal marks. 7. Before you proceed to mark in the Answer Sheet the response to various items in the Test Booklet, you have to fill in the some particulars in the Answer Sheet as per instructions sent to you with your Admission Certificate. 8. After you have completed filling in all your responses on the Answer Sheet and the examina- tion has concluded, you should hand over to the invigilator only the Answer Sheet. -

PAPER 1 DSE-A-1 SEM -5: HISTORY of BENGAL(C.1757-1905) IV

PAPER 1 DSE-A-1 SEM -5: HISTORY OF BENGAL(c.1757-1905) IV. CULTURAL CHANGES AND SOCIAL AND RELIGIOUS REFORM MOVEMENT PART 2 The growth of nationalism and democracy, which led to the struggle for freedom, also found expression in movements to reform and democratise the social institutions and religious outlook of the Indian people. Many Indians realised that social and religious reformation was an essential condition for the all-round development of the country on modern lines and for the growth of national unity and solidarity. The growth of nationalist sentiments, emergence of new economic forces, spread of education, impact of modern western ideas and culture, and increased awareness of the world not only heightened the consciousness of the backwardness and degeneration of Indian society but further strengthened the resolve to reform. Thus, after 1858, the earlier reforming tendency was broadened. The work of earlier reformers, like Raja Rammohun Roy and Pandit Vidyasagar, was carried further by major movements of religious and social reform. Brahmo Samaj Rammohun Roy established the Atmiya Sabha in Calcutta in 1815 in order to propagate monotheism and to fight against the evil customs and practices in Hinduism. Later in 1828 he established the Brahmo Samaj with the same aim. After a long struggle against the practice of Sati he was finally successful in 1829 in abolishing Sati with the help of William Bentinck. The Brahmo tradition of Raja Rammohun Roy was carried forward after 1843 by Devendranath Tagore, who also repudiated the doctrine that the Vedic scriptures were infallible, and after 1866 by Keshub Chandra Sen. -

History of Modern Maharashtra – Paper 5

HISTORY OF MODERN MAHARASHTRA – PAPER 5 QUESTION BANK 1. From the reign of Chhatrapati Shahu, the _______became the de facto rulers of the Maratha state. a. Mahajans b. Peshwa c. Punditrao d. Nyaydish 2. Who was the first editor of Kesari ? a. Maharshi Karve b. vishnu shastri chiplunkar c. Gopal Ganesh Agarkar d. Lokmanya Tilak 3. The 'Drain Theory' was propounded by a. G.V. Joshi b. R. Ambedkar c. G. K. Gokhale d. Dadabhai Naoroji 4. Who become the first female teacher of Maharashtra a. Anandi Gopal b. Ramabai Ranade c. Pandita ramabai d. Savitribai Phule 5. Who what the founder Rayat shikshan Sanstha a. Shahu Maharaj b. Dr.R. Ambedkar c. karmaveer bhaurao Patil d. Mahatma Phule 6. The Indian Depressed Classes Mission was established by ______. a. G.K. Gokhale b. Shahu Maharaj c. Dr. R. Ambedkar d. Vithhal Ramji Shinde 7. The book ‘Annihilation of Caste' was written by a. Vitthal Ramji Shinde b. Jotirao Phule c. Bhau Mahajan d. Dr. R. Ambedkar 8. The evil practice of widow burning was called__________. a. Tonsuring b. Balutedari c. Devdasi d. Sati 9. The ________________ movement was started to unite all Marathi speaking regions into one state. a. Gujarat and Maharashtra b. Samyukta Maharashtra c. Vidharbha d. Chalo Delhi 10. Under whose leadership Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti was founded a. Shripad Amrit Dange b. Keshavrao Jedhe c. Uddhavrao Patil d. Narayan Ganesh Gore 11. In what year did Jagannath shankar sheth establish a school a. 1890 b. 1880 c. 1857 d. 1854 12. Who was the first president of the DnyPrasarak sabha a. -

Modern Indian Political Thought Political Indian Modern

MODERN INDIAN POLITICAL THOUGHT PAPER - II POLITICAL SCIENCE M.A. PART - I Dr. Rajan Welukar Dr. D. Harichandan Vice Chancellor, Professor-Cum-Director , University Of Mumbai IDOL, University Of Mumbai Programme Co-ordinator : Shri Anil Bankar Asst.Prof. Cum Asst Director IDOL, University Of Mumbai Course Co-ordinator : Dr. Surendra Jondhale Head, Department of Civics & Politics University Of Mumbai Mumbai - 400098 Editor & Course Writer 1) Dr. Chhaya Bakane, Principal, R. J. Thakur College Thane (W) Course Writer 2) Prof . S. Zaheer Ali Department of Civics & Politics University Of Mumbai Mumbai - 400098 3) Dr. M. Murlidhara, Behind Barrach, 1081, O.T. Section, Ashok Nagar Ulhasnagar 4) Prof S. P. Buwa T. K Tope Night College, Parel, Mumbai-400012 MAY, 2012 – M.A. PART - I, Modern Indian Political Thought Politicals Science Paper - II Publisher : Dr. D. Harichandan Professor-Cum-Director IDOL, University Of Mumbai Mumbai – 400098 DTP Compossed by : Gaokar’s Laser Point Borivali (W), Mumbai -400092 INDEX Units Title Page No. 1. The Indian Renaissance - Raja Ram Mohan Roy, 1 Swami Vivekananda 2. Equality: Contribution of Jyotiba Phule (1827-1890) 23 3. Equality: contribution of Dr. B.R.Ambedkar 32 Training and Development 4. Mahadeo Govind Ranade 43 5. Gopal Krishna Gokhale 59 6. Extremism and Political Thoughts of Tilak and Aurobindo 88 7. Bal Gangadhar Tilak 106 8. Aurobindo Ghosh 132 9. Trust and Non-violence : Mahatma Gandhi 151 10. Truth and Non-violence and Gandhian Ideas 165 11. Sarvodaya - Vinoba Bhave 176 12. Jayaprakash Narayan 190 13. Communalism: Hindu, Muslim and Sikh 203 14. Socialist and communist Thought - 224 Dr. -

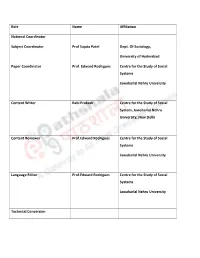

Role Name Affiliation National Coordinator Subject Coordinator Prof Sujata Patel Dept. of Sociology, University of Hyderaba

Role Name Affiliation National Coordinator Subject Coordinator Prof Sujata Patel Dept. Of Sociology, University of Hyderabad Paper Coordinator Prof. Edward Rodrigues Centre for the Study of Social Systems Jawaharlal Nehru University Content Writer Rabi Prakash Centre for the Study of Social System, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Content Reviewer Prof.Edward Rodrigues Centre for the Study of Social Systems Jawaharlal Nehru University Language Editor Prof.Edward Rodrigues Centre for the Study of Social Systems Jawaharlal Nehru University Technical Conversion Module Structure Hindu Reform Movement This module offers historical-sociological analysis of the intellectual movements of the 19th century India, which, as a set of organized efforts aimed to effectuate social and religious reforms in Hindu society. This module would provide an account of the social reform movements, introduced in the 19th century, and would place the argument that these movements need to be seen as the Hindu elites’ intellectual and social response to colonial discourse and its socio- cultural policy, informed and driven by the ideals and ideologies of the 19th century Europe. Further, it suggests that intellectual encounters between Indian elites and colonial discourse, in socio-cultural, religious and political domain be studied under the complex backdrop of emergent Indian nationalism and its concerns for existing social concerns (Heimsath, C. H., 1964). Description of the Module Items Description of the Module Subject Name Sociology Paper Name Religion