DECODING the PRESENCE of WOMEN in the REFORMIST-NATIONALIST MOVEMENTS of the NINETEENTH CENTURY in INDIA THROUGH RAMABAI Rakesh Singh Paraste1 and Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

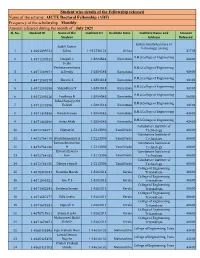

Student Wise Details of the Fellowship Released Name of the Scheme

Student wise details of the Fellowship released Name of the scheme: AICTE Doctoral Fellowship (ADF) Frequency of the scholarship –Monthly Amount released during the month of : July 2021 Sl. No. Student ID Name of the Institute ID Institute State Institute Name and Amount Student Address Released Indira Gandhi Institute of Sushil Kumar Technology, Sarang 1 1-4064399722 Sahoo 1-412736121 Orissa 31703 B.M.S.College of Engineering 2 1-4071237529 Deepak C 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Perla Venkatasreenivasu B.M.S.College of Engineering 3 1-4071249071 la Reddy 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 4 1-4071249170 Shruthi S 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 5 1-4071249196 Vidyadhara V 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 6 1-4071249216 Pruthvija B 1-5884543 Karnataka 86800 Tulasi Naga Jyothi B.M.S.College of Engineering 7 1-4071249296 Kolanti 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 8 1-4071448346 Manali Raman 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 9 1-4071448396 Anisa Aftab 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Coimbatore Institute of 10 1-4072764071 Vijayan M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 11 1-4072764119 Sivasubramani P A 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Ramasubramanian Coimbatore Institute of 12 1-4072764136 M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Eswara Eswara Coimbatore Institute of 13 1-4072764153 Rao 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 14 1-4072764158 Dhivya Priya N 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 -

Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of Higher Education

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 2276 TO BE ANSWERED ON 02.12.2019 Universities 2276. SHRI COSME FRANCISCO CAITANO SARDINHA: Will the Minister of HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT be pleased to state: (a) whether any University in our country figures in the list of good universities listed by the international agencies; (b) if so, the details thereof; and (c) if not, the reasons therefor? ANSWER MINISTER OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT (SHRI RAMESH POKHRIYAL ‘NISHANK’) (a) & (b): Yes, Sir. As per Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings-2020 and Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) World University Ranking-2020, 36 and 24 Indian Universities / Institutions respectively figure in the top 1000 World University Rankings. The details of these Institutions / Universities are at Annexure-I. (c): In view of the above, does not arise. Annexure-I ANNEXURE REFERRED IN REPLY TO PART (a) AND (b) OF LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 2276 TO BE ANSWERED ON 02.12.2019 ASKED BY HONBLE MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT SHRI COSME FRANCISCO CAITANO SARDINHA REGARDING UNIVERSITIES List of Institutions / Universities found placed in top 1000 of world reputed ranking Agencies Agency THE World University Ranking QS World University Ranking-2020 Sl No. 2020 (Position) (Position) i. IISc, Bangalore – 301-350 IIT, Bombay - 152 ii. IIT, Ropar – 301-350 IIT, Delhi – 182 iii. IIT, Indore – 351-400 IISc, Bangalore - 184 iv. IIT, Bombay – 401-500 IIT, Madras – 271 v. IIT, Delhi - 401-500 IIT, Kharagpur – 281 vi. IIT, Kharagpur – 401-500 IIT, Kanpur - 291 vii. Institute of Chemical Technology, IIT, Roorkee – 383 Mumabi – 501-600 viii. -

Question Bank Mcqs TYBA Political Science Semester V 2019-20 Paper-6 Politics of Modern Maharashtra

Question Bank MCQs TYBA Political Science Semester V 2019-20 Paper-6 Politics of Modern Maharashtra 1. Who founded the SNDT University for women in 1916? a) M.G.Ranade b) Dhondo Keshav Karve c) Gopal Krishna Gokhale d) Bal Gangadhar Tilak 2. Who was associated with the Satyashodhak Samaj? a) Sri Narayan Guru b) Jyotirao Phule c) Dr. B. R. Ambedkar d) E.V. Ramaswamy Naicker 3. When was the Indian National Congress established? a) 1875 b) 1885 c) 1905 d) 1947 4. Which Marathi newspaper was published by Bal Gangadhar Tilak a) Kesari b) Poona Vaibhav c) Sakal d) Darpan 5. Which day is celebrated as the Maharashtra Day? a) 12th January b) 14th April c) 1st May d) 2nd October 6. Under whose leadership Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti was founded? a) Keshavrao Jedhe b) S. A. Sange c) Uddhavrao Patil d) Narayan Ganesh Gore 7. When did the Bilingual Bombay State come into existence? a) 1960 b) 1962 c) 1956 d) 1947 8. Which one of the following city comes under Vidarbha region? a) Nagpur b) Poona c) Aurangabad d) Raigad 9. Till 1948 Marathwada region was part of which of the following? a) Central Province and Berar b) Bombay State c) Hyderabad State d) Junagad 10. Dandekar Committee dealt with which of the following issues? a) Maharashtra’s Educational policy b) The problem of imbalance in development between different regions of Maharashtra c) Trade and commerce policy of Maharashtra d) Agricultural policy 11. Which one of the following is known as the financial capital of India? a) Pune b) Mumbai c) Nagpur d) Aurangabad 12. -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

Title: Women of Agency: the Penned Thoughts of Bengali Muslim

Title: Women of Agency: The Penned Thoughts of Bengali Muslim Women Writers of 9th 20th the Late 1 and Early Century Submitted by: Irteza Binte-Farid In Fulfillment of the Feminist Studies Honors Program Date: June 3, 2013 introduction: With the prolusion of postcolornal literature and theory arising since the 1 9$Os. unearthing subaltern voices has become an admirable task that many respected scholars have undertaken. Especially in regards to South Asia, there has been a series of meticulouslyresearched and nuanced arguments about the role of the subaltern in contributing to the major annals of history that had previously been unrecorded, greatly enriching the study of the history of colonialism and imperialism in South Asia. 20th The case of Bengali Muslim women in India in the late l91 and early century has also proven to be a topic that has produced a great deal of recent literature. With a history of scholarly 19th texts, unearthing the voices of Hindu Bengali middle-class women of late and early 2O’ century, scholars felt that there was a lack of representation of the voices of Muslim Bengali middle-class women of the same time period. In order to counter the overwhelming invisibility of Muslim Bengali women in academic scholarship, scholars, such as Sonia Nishat Amin, tackled the difficult task of presenting the view of Muslim Bengali women. Not only do these new works fill the void of representing an entire community. they also break the persistent representation of Muslim women as ‘backward,’ within normative historical accounts by giving voice to their own views about education, religion, and society) However, any attempt to make ‘invisible’ histories ‘visible’ falls into a few difficulties. -

The Imperial and the Colonized Women's Viewing of the 'Other'

Gazing across the Divide in the Days of the Raj: The Imperial and the Colonized Women’s Viewing of the ‘Other’ Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Sukla Chatterjee Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans Harder Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Benjamin Zachariah Heidelberg, 01.04.2016 Abstract This project investigates the crucial moment of social transformation of the colonized Bengali society in the nineteenth century, when Bengali women and their bodies were being used as the site of interaction for colonial, social, political, and cultural forces, subsequently giving birth to the ‘new woman.’ What did the ‘new woman’ think about themselves, their colonial counterparts, and where did they see themselves in the newly reordered Bengali society, are some of the crucial questions this thesis answers. Both colonial and colonized women have been secondary stakeholders of colonialism and due to the power asymmetry, colonial woman have found themselves in a relatively advantageous position to form perspectives and generate voluminous discourse on the colonized women. The research uses that as the point of departure and tries to shed light on the other side of the divide, where Bengali women use the residual freedom and colonial reforms to hone their gaze and form their perspectives on their western counterparts. Each chapter of the thesis deals with a particular aspect of the colonized women’s literary representation of the ‘other’. The first chapter on Krishnabhabini Das’ travelogue, A Bengali Woman in England (1885), makes a comparative ethnographic analysis of Bengal and England, to provide the recipe for a utopian society, which Bengal should strive to become. -

The Pneumatic Experiences of the Indian Neocharismatics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE PNEUMATIC EXPERIENCES OF THE INDIAN NEOCHARISMATICS By JOY T. SAMUEL A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham June 2018 i University of Birmingham Research e-thesis repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and /or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any success or legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. i The Abstract of the Thesis This thesis elucidates the Spirit practices of Neocharismatic movements in India. Ever since the appearance of Charismatic movements, the Spirit theology has developed as a distinct kind of popular theology. The Neocharismatic movement in India developed within the last twenty years recapitulates Pentecostal nature spirituality with contextual applications. Pentecostalism has broadened itself accommodating all churches as widely diverse as healing emphasized, prosperity oriented free independent churches. Therefore, this study aims to analyse the Neocharismatic churches in Kerala, India; its relationship to Indian Pentecostalism and compares the Sprit practices. It is argued that the pneumatology practiced by the Neocharismatics in Kerala, is closely connected to the spirituality experienced by the Indian Pentecostals. -

Abstract Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, Anti

ABSTRACT KAMALADEVI CHATTOPADHYAYA, ANTI-IMPERIALIST AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS ACTIVIST, 1939-41 by Julie Laut Barbieri This paper utilizes biographies, correspondence, and newspapers to document and analyze the Indian socialist and women’s rights activist Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya’s (1903-1986) June 1939-November 1941 world tour. Kamaladevi’s radical stance on the nationalist cause, birth control, and women’s rights led Gandhi to block her ascension within the Indian National Congress leadership, partially contributing to her decision to leave in 1939. In Europe to attend several international women’s conferences, Kamaladevi then spent eighteen months in the U.S. visiting luminaries such as Eleanor Roosevelt and Margaret Sanger, lecturing on politics in India, and observing numerous social reform programs. This paper argues that Kamaladevi’s experience within Congress throughout the 1930s demonstrates the importance of gender in Indian nationalist politics; that her critique of Western “international” women’s organizations must be acknowledged as a precursor to the politics of modern third world feminism; and finally, Kamaladevi is one of the twentieth century’s truly global historical agents. KAMALADEVI CHATTOPADHYAYA, ANTI-IMPERIALIST AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS ACTIVIST, 1939-41 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History By Julie Laut Barbieri Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2008 Advisor____________________________ (Judith P. Zinsser) Reader_____________________________ (Mary E. Frederickson) Reader_____________________________ (David M. Fahey) © Julie Laut Barbieri 2008 For Julian and Celia who inspire me to live a purposeful life. Acknowledgements March 2003 was an eventful month. While my husband was in Seattle at a monthly graduate school session, I discovered I was pregnant with my second child. -

Open Chindhade Final Dissertation

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of German PRESENTING AND COMPARING EARLY MARATHI AND GERMAN WOMEN’S FEMINIST WRITINGS (1866-1933): SOME FINDINGS A Dissertation in German by Tejashri Chindhade © 2010 Tejashri Chindhade Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 The dissertation of Tejashri Chindhade was reviewed and approved* by the following: Daniel Purdy Associate Professor of German Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Thomas.O. Beebee Professor of Comparative Literature and German Reiko Tachibana Associate Professor of Japanese and Comparative Literature Kumkum Chatterjee Associate Professor of South Asia Studies B. Richard Page Associate Professor of German and Linguistics Head of the Department of German *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract In this dissertation I present the feminist writings of four Marathi women writers/ activists Savitribai Phule’s “ Prose and Poetry”, Pandita Ramabai’s” The High Caste Hindu Woman”, Tarabai Shinde’s “Stri Purush Tualna”( A comparison between women and men) and Malatibai Bedekar’s “Kalyanche Nihshwas”( “The Sighs of the buds”) from the colonial period (1887-1933) and compare them with the feminist writings of four German feminists: Adelheid Popp’s “Jugend einer Arbeiterin”(Autobiography of a Working Woman), Louise Otto Peters’s “Das Recht der Frauen auf Erwerb”(The Right of women to earn a living..), Hedwig Dohm’s “Der Frauen Natur und Recht” (“Women’s Nature and Privilege”) and Irmgard Keun’s “Gilgi: Eine Von Uns”(Gilgi:one of us) (1886-1931), respectively. This will be done from the point of view of deconstructing stereotypical representations of Indian women as they appear in westocentric practices. -

Unit 12 Resistance and Protest* Structure 12.0 Objectives 12.1 Introduction 12.2 Caste

Unit 12 Resistance and Protest* Structure 12.0 Objectives 12.1 Introduction 12.2 Caste: Characteristic of Indian Society 12.2.1 Caste and the Ideology of Hierarchy 12.3 Early Critiques and Struggles 12.3.1 Feminist Crusade against the Patriarchy: Rambai, Tarabai and Beyond 12.3.2 Contributions of Phule and Ambedkar: Dalits' Fight against caste Oppression 12.4. The New Social Movements and the Caste Question 12.5 Lets Sum Up 12.6 Key Words 12.7 Further Readings 12.8 Specimen Answers 12.0 Objectives After reading this unit, you should be able to: elaborate that caste practices and rituals have met with strong resistance and protest; understand that culture of resistance and protest at the intellectual and religious level ; Discuss subaltern perspectives on caste. * * written by Kanika Kakar, Delhi University 1 12.1 Introduction There is a common perception regarding Hinduism subscribed by its adherents that relates essentially to its pluralistic content and tolerant tradition. This portrayal of Hinduism as a template for tolerance glosses over its most divisive element — caste and silences the struggles and protests launched by those outside the Hindu framework. To regard India in the context of single-system of Hindu conception of social order is therefore inadequate. The resistance and protests launched by non-Hindu and non-Brahmanical forces makes it necessary to relate theory of social structure with the idea of change. They bring into questioning the functional presuppositions of social system/caste system (Singh, Yogendra 1986:66) and the dominant idea that India is a nation of Hindus. -

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination by Purvi Mehta A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Chair Professor Pamela Ballinger Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Matthew Hull Professor Mrinalini Sinha Dedication For my sister, Prapti Mehta ii Acknowledgements I thank the dalit activists that generously shared their work with me. These activists – including those at the National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights, Navsarjan Trust, and the National Federation of Dalit Women – gave time and energy to support me and my research in India. Thank you. The research for this dissertation was conducting with funding from Rackham Graduate School, the Eisenberg Center for Historical Studies, the Institute for Research on Women and Gender, the Center for Comparative and International Studies, and the Nonprofit and Public Management Center. I thank these institutions for their support. I thank my dissertation committee at the University of Michigan for their years of guidance. My adviser, Farina Mir, supported every step of the process leading up to and including this dissertation. I thank her for her years of dedication and mentorship. Pamela Ballinger, David Cohen, Fernando Coronil, Matthew Hull, and Mrinalini Sinha posed challenging questions, offered analytical and conceptual clarity, and encouraged me to find my voice. I thank them for their intellectual generosity and commitment to me and my project. Diana Denney, Kathleen King, and Lorna Altstetter helped me navigate through graduate training. -

Chapter 8 Women and Reform Exercises Tick the Correct Option 1

Chapter 8 Women and Reform Exercises Tick the correct option 1. She was the first graduate women of India Ans. Kadambini Basu 2.A woman who died on her husband's pyre was termed as Ans. Sati 3 He was the first Indian to protest against the custom of women die as satis. Ans. Raja Ram Mohan Roy 4. Who founded the Ramakrishna mission in 1897 Ans. Swami Vivekananda 5. According to NFHS-III,which of these States has the lowest percentage of child marriage? Ans. Himachal Pradesh 6. Amar jiban is the autobiography of Ans. Rassundari Devi State true or false 1. Ramabai Ranade autobiography was written in Telugu. (False) 2.Ruqaiya Hussain wrote extensively against parda practice in her book.(true) 3.the age of consent bill was passed for the prevention of child marriage. (True) 4. Sati system was prevalent only in few parts of India in the ancient times. (False) 5. Child marriage has been wiped out completely from our society. (False) Short answer questions Q1. Why many Indian women were denied education in the 19th century? Ans. Indian women were denied education in the 19th century because the majority believe that education would create a bad influence on girls mind. Q2. What is sati system? Why was it so prevalent in the ancient times? Ans. A woman whose husband died was burnt alive on the husband's pyre. Such an act was considered virtuous and the woman was termed as sati. The sati system was prevalent in many places in India since ancient time. According to this Hindu custom are wife immolated herself at the funeral pyre of her husband.