Open Chindhade Final Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gynocentrism As a Narcissistic Pathology

24 GYNOCENTRISM AS A NARCISSISTIC PATHOLOGY Peter Wright ABSTRACT Gynocentrism is defined as the practice of prioritizing the needs, wants and desires of women. Examples of gynocentrism are found in the culture of social institutions, and within heterosexual relationships where men are invited to show deference to the needs, wants and desires of women, a practice otherwise referred to as chivalry or benevolent sexism. This study compares gynocentric behaviors with clinical descriptions of narcissism to discover how closely, and in what ways, the two concepts align. The investigation concludes that narcissistic behavior is significantly correlated with behaviors of gynocentrically oriented women, and that gynocentrism is a gendered expression of narcissism operating within the limiting context of heterosexual relationships and exchanges. Keywords: Gynocentrism, chivalry, benevolent sexism, narcissism, narcissistic personality inventory, gender NEW MALE STUDIES: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ~ ISSN 1839-7816 ~ Vol 9, Issue 1, 2020, Pp. 24–49 © 2020 AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF MALE HEALTH AND STUDIES 25 INTRODUCTION Gynocentrism has been described as a practice of prioritizing the needs, wants and desires of women over those of men. It operates within a moral hierarchy that emphasizes the innate virtues and vulnerabilities of women and the innate vices of men, thus providing a rationale for placing women’s concerns and perspectives ‘on top’, and men’s at the bottom (Nathanson & Young, 2006; 2010). The same moral hierarchy has been institutionalized in social conventions, laws and interpretations of them, in constitutional amendments and their interpretive guidelines, and bureaucracies at every level of government, making gynocentrism de rigueur behind the scenes in law courts and government bureaucracies that result in systemic discrimination against men (Nathanson & Young, 2006; Wright, 2018a; Wallace et al., 2019; Naurin, 2019). -

My German-Jewish Legacy and Theirs Anthony Heilbut

My German-Jewish Legacy and Theirs Anthony Heilbut This German-Jewish legacy, how German is it? and how Jewish? Moreover, what kind of Germans? what sort of Jews? Who inherits this legacy, a Joseph or a Judah? What legacy do our Joseph and Judah select? Surely not the same one. It's typically German, typically Jew- ish, typically German-Jewish to stress the uniqueness of one's group, attended by an inexorable ambivalence, another specialty of the three groups in question. A perfectly straightforward issue is posed, and immediately my tone seems captious. I have two explanations: a general one-I'm upset by any form of cultural nationalism-and one more immediate: A few months ago, I spoke with a young German. He was both effusive in his praise of German Jewry and obsequious in his apology for crimes committed years before his birth. (In Germany, wallowing in guilt and self-pity seems as timeless as bad taste.) Finally he revealed his agenda: "Let's face it," he said. "Germans are the best people, and Jews make the best Germans." Aha, I thought, there you go. We're either the best or not good enough. Much about the German-Jewish legacy eludes facile generalization, starting with the question of Germanness. Consider my family's com- plicated roots. The son of a Hamburg father and a London mother, my father was born in Amsterdam. Maritime links between his parents' cities helped make the Hamburgers spirited Anglophiles. For Ham- burg Jews as well, British connections added a whiff of cosmopolitan style, particularly during the nineteenth century when German--or German-Jewish-identity was newly formed and tentative. -

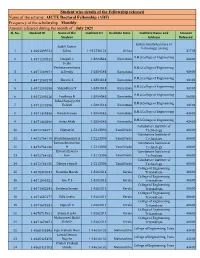

Student Wise Details of the Fellowship Released Name of the Scheme

Student wise details of the Fellowship released Name of the scheme: AICTE Doctoral Fellowship (ADF) Frequency of the scholarship –Monthly Amount released during the month of : July 2021 Sl. No. Student ID Name of the Institute ID Institute State Institute Name and Amount Student Address Released Indira Gandhi Institute of Sushil Kumar Technology, Sarang 1 1-4064399722 Sahoo 1-412736121 Orissa 31703 B.M.S.College of Engineering 2 1-4071237529 Deepak C 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Perla Venkatasreenivasu B.M.S.College of Engineering 3 1-4071249071 la Reddy 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 4 1-4071249170 Shruthi S 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 5 1-4071249196 Vidyadhara V 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 6 1-4071249216 Pruthvija B 1-5884543 Karnataka 86800 Tulasi Naga Jyothi B.M.S.College of Engineering 7 1-4071249296 Kolanti 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 8 1-4071448346 Manali Raman 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 9 1-4071448396 Anisa Aftab 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Coimbatore Institute of 10 1-4072764071 Vijayan M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 11 1-4072764119 Sivasubramani P A 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Ramasubramanian Coimbatore Institute of 12 1-4072764136 M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Eswara Eswara Coimbatore Institute of 13 1-4072764153 Rao 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 14 1-4072764158 Dhivya Priya N 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 -

Femininity and Dress in fic- Tion by German Women Writers, 1840-1910

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Scripts, skirts, and stays: femininity and dress in fic- tion by German women writers, 1840-1910 https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40147/ Version: Full Version Citation: Nevin, Elodie (2015) Scripts, skirts, and stays: femininity and dress in fiction by German women writers, 1840-1910. [Thesis] (Unpub- lished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Scripts, Skirts, and Stays: Femininity and Dress in Fiction by German Women Writers, 1840-1910 Elodie Nevin Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in German 2015 Department of European Cultures and Languages Birkbeck, University of London Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood the regulations for students of Birkbeck, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. Signed: Date: 12/08/2015 2 Abstract This thesis examines the importance of sartorial detail in fiction by German women writers of the nineteenth century. Using a methodology based on Judith Butler’s gender theory, it examines how femininity is perceived and presented and argues that clothes are essential to female characterisation and both the perpetuation and breakdown of gender stereotypes. -

Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of Higher Education

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 2276 TO BE ANSWERED ON 02.12.2019 Universities 2276. SHRI COSME FRANCISCO CAITANO SARDINHA: Will the Minister of HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT be pleased to state: (a) whether any University in our country figures in the list of good universities listed by the international agencies; (b) if so, the details thereof; and (c) if not, the reasons therefor? ANSWER MINISTER OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT (SHRI RAMESH POKHRIYAL ‘NISHANK’) (a) & (b): Yes, Sir. As per Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings-2020 and Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) World University Ranking-2020, 36 and 24 Indian Universities / Institutions respectively figure in the top 1000 World University Rankings. The details of these Institutions / Universities are at Annexure-I. (c): In view of the above, does not arise. Annexure-I ANNEXURE REFERRED IN REPLY TO PART (a) AND (b) OF LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 2276 TO BE ANSWERED ON 02.12.2019 ASKED BY HONBLE MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT SHRI COSME FRANCISCO CAITANO SARDINHA REGARDING UNIVERSITIES List of Institutions / Universities found placed in top 1000 of world reputed ranking Agencies Agency THE World University Ranking QS World University Ranking-2020 Sl No. 2020 (Position) (Position) i. IISc, Bangalore – 301-350 IIT, Bombay - 152 ii. IIT, Ropar – 301-350 IIT, Delhi – 182 iii. IIT, Indore – 351-400 IISc, Bangalore - 184 iv. IIT, Bombay – 401-500 IIT, Madras – 271 v. IIT, Delhi - 401-500 IIT, Kharagpur – 281 vi. IIT, Kharagpur – 401-500 IIT, Kanpur - 291 vii. Institute of Chemical Technology, IIT, Roorkee – 383 Mumabi – 501-600 viii. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Satara. in 1960, the North Satara Reverted to Its Original Name Satara, and South Satara Was Designated As Sangli District

MAHARASHTRA STATE GAZETTEERS Government of Maharashtra SATARA DISTRICT (REVISED EDITION) BOMBAY DIRECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, STATIONARY AND PUBLICATION, MAHARASHTRA STATE 1963 Contents PROLOGUE I am very glad to bring out the e-Book Edition (CD version) of the Satara District Gazetteer published by the Gazetteers Department. This CD version is a part of a scheme of preparing compact discs of earlier published District Gazetteers. Satara District Gazetteer was published in 1963. It contains authentic and useful information on several aspects of the district and is considered to be of great value to administrators, scholars and general readers. The copies of this edition are now out of stock. Considering its utility, therefore, need was felt to preserve this treasure of knowledge. In this age of modernization, information and technology have become key words. To keep pace with the changing need of hour, I have decided to bring out CD version of this edition with little statistical supplementary and some photographs. It is also made available on the website of the state government www.maharashtra.gov.in. I am sure, scholars and studious persons across the world will find this CD immensely beneficial. I am thankful to the Honourable Minister, Shri. Ashokrao Chavan (Industries and Mines, Cultural Affairs and Protocol), and the Minister of State, Shri. Rana Jagjitsinh Patil (Agriculture, Industries and Cultural Affairs), Shri. Bhushan Gagrani (Secretary, Cultural Affairs), Government of Maharashtra for being constant source of inspiration. Place: Mumbai DR. ARUNCHANDRA S. PATHAK Date :25th December, 2006 Executive Editor and Secretary Contents PREFACE THE GAZETTEER of the Bombay Presidency was originally compiled between 1874 and 1884, though the actual publication of the volumes was spread over a period of 27 years. -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

7. Not So Romantic for Men

DENNIS S. GOUWS 7. NOT SO ROMANTIC FOR MEN Using Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe to Explore Evolving Notions of Chivalry and Their Impact on Twenty-First-Century Manhood THE NEED FOR A NEW MALE STUDIES The New Male Studies offer an alternative to conventional gender-based scholarship on boys and men.1 Unlike Men’s-Studies research, which is fundamentally informed by gender feminism, New-Male-Studies research focusses on boys’ and men’s lived experiences and shares its concern about gender discrimination against all people with equity feminism.2 The New Male Studies are embodied and male positive (male affirming): their approach to manhood, which results when one “configure[s] biological masculinity to meet the particular demands of a specific culture and environmental setting,” not only celebrates males’ experience of different manhood cultures and subcultures, but also critiques—and suggests strategies for overcoming—systemic inhibitors of masculine affirmation (Ashfield, 2011, p. 28; Gilmore, 1990). An acute attentiveness to how manhood is inscribed in texts, textual criticism, and pedagogy is central to their methodology. In much of Western culture and literature, gynocentric (women-centered) and misandric (male-hating) value judgments have adversely influenced boys’ and men’s lives. For example, pervasive stereotypes of manhood that rely on gynocentric and misandric assumptions about males infer that it is acceptable to regard them as little more than pleasers, placaters, providers, protectors, and progenitors; such stereotypes assume the male body is primarily an instrument of service rather than the dignified embodiment of a sentient boy or a man (Nathanson & Young, 2001, 2006, 2010). -

Germany from Luther to Bismarck

University of California at San Diego HIEU 132 GERMANY FROM LUTHER TO BISMARCK Fall quarter 2009 #658659 Class meets Tuesdays and Thursdays from 2 until 3:20 in Warren Lecture Hall 2111 Professor Deborah Hertz Humanities and Social Science Building 6024 534 5501 Readers of the papers and examinations: Ms Monique Wiesmueller, [email protected]. Office Hours: Wednesdays 1:30 to 3 and by appointment CONTACTING THE PROFESSOR Please do not contact me by e-mail, but instead speak to me before or after class or on the phone during my office hour. I check the mailbox inside of our web site regularly. In an emergency you may contact the assistant to the Judaic Studies Program, Ms. Dorothy Wagoner at [email protected]; 534 4551. CLASSROOM ETIQUETTE. Please do not eat in class, drinks are acceptable. Please note that you should have your laptops, cell phones, and any other devices turned off during class. Students do too much multi-tasking for 1 the instructor to monitor. Try the simple beauty of a notebook and a pen. If so many students did not shop during class, you could enjoy the privilege of taking notes on your laptops. Power point presentations in class are a gift to those who attend and will not be available on the class web site. Attendance is not taken in class. Come to learn and to discuss. Class texts: All of the texts have been ordered with Groundworks Books in the Old Student Center and have been placed on Library Reserve. We have a systematic problem that Triton Link does not list the Groundworks booklists, but privileges the Price Center Bookstore. -

The Pneumatic Experiences of the Indian Neocharismatics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE PNEUMATIC EXPERIENCES OF THE INDIAN NEOCHARISMATICS By JOY T. SAMUEL A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham June 2018 i University of Birmingham Research e-thesis repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and /or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any success or legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. i The Abstract of the Thesis This thesis elucidates the Spirit practices of Neocharismatic movements in India. Ever since the appearance of Charismatic movements, the Spirit theology has developed as a distinct kind of popular theology. The Neocharismatic movement in India developed within the last twenty years recapitulates Pentecostal nature spirituality with contextual applications. Pentecostalism has broadened itself accommodating all churches as widely diverse as healing emphasized, prosperity oriented free independent churches. Therefore, this study aims to analyse the Neocharismatic churches in Kerala, India; its relationship to Indian Pentecostalism and compares the Sprit practices. It is argued that the pneumatology practiced by the Neocharismatics in Kerala, is closely connected to the spirituality experienced by the Indian Pentecostals. -

Abstract Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, Anti

ABSTRACT KAMALADEVI CHATTOPADHYAYA, ANTI-IMPERIALIST AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS ACTIVIST, 1939-41 by Julie Laut Barbieri This paper utilizes biographies, correspondence, and newspapers to document and analyze the Indian socialist and women’s rights activist Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya’s (1903-1986) June 1939-November 1941 world tour. Kamaladevi’s radical stance on the nationalist cause, birth control, and women’s rights led Gandhi to block her ascension within the Indian National Congress leadership, partially contributing to her decision to leave in 1939. In Europe to attend several international women’s conferences, Kamaladevi then spent eighteen months in the U.S. visiting luminaries such as Eleanor Roosevelt and Margaret Sanger, lecturing on politics in India, and observing numerous social reform programs. This paper argues that Kamaladevi’s experience within Congress throughout the 1930s demonstrates the importance of gender in Indian nationalist politics; that her critique of Western “international” women’s organizations must be acknowledged as a precursor to the politics of modern third world feminism; and finally, Kamaladevi is one of the twentieth century’s truly global historical agents. KAMALADEVI CHATTOPADHYAYA, ANTI-IMPERIALIST AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS ACTIVIST, 1939-41 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History By Julie Laut Barbieri Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2008 Advisor____________________________ (Judith P. Zinsser) Reader_____________________________ (Mary E. Frederickson) Reader_____________________________ (David M. Fahey) © Julie Laut Barbieri 2008 For Julian and Celia who inspire me to live a purposeful life. Acknowledgements March 2003 was an eventful month. While my husband was in Seattle at a monthly graduate school session, I discovered I was pregnant with my second child.