The Pneumatic Experiences of the Indian Neocharismatics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

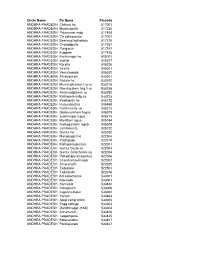

Post Offices

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

Directory 2017

DISTRICT DIRECTORY / PATHANAMTHITTA / 2017 INDEX Kerala RajBhavan……..........…………………………….7 Chief Minister & Ministers………………..........………7-9 Speaker &Deputy Speaker…………………….................9 M.P…………………………………………..............……….10 MLA……………………………………….....................10-11 District Panchayat………….........................................…11 Collectorate………………..........................................11-12 Devaswom Board…………….............................................12 Sabarimala………...............................................…......12-16 Agriculture………….....…...........................……….......16-17 Animal Husbandry……….......………………....................18 Audit……………………………………….............…..…….19 Banks (Commercial)……………..................………...19-21 Block Panchayat……………………………..........……….21 BSNL…………………………………………….........……..21 Civil Supplies……………………………...............……….22 Co-Operation…………………………………..............…..22 Courts………………………………….....................……….22 Culture………………………………........................………24 Dairy Development…………………………..........………24 Defence……………………………………….............…....24 Development Corporations………………………...……24 Drugs Control……………………………………..........…24 Economics&Statistics……………………....................….24 Education……………………………................………25-26 Electrical Inspectorate…………………………...........….26 Employment Exchange…………………………...............26 Excise…………………………………………….............….26 Fire&Rescue Services…………………………........……27 Fisheries………………………………………................….27 Food Safety………………………………............…………27 -

Pathanamthitta

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory PATHANAMTHITTA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 105 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at 2011 Census (b) -

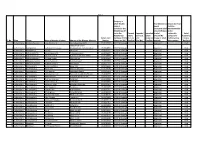

Page1 Sl. No Taluk Village Name of Disaster Affected Address of The

Page1 Category in which his/her Final Decision in Reason for Final house is appeal Decision included in the (Increased relief (Recommended Rebuild App (If amount/Reduce by the not in the Claimed Appealed Appealed d relief Technically Relief Rebuild App before before 31- before amount/No Competent Assistance Ration Card Database fill the 31-1-19 3-19 30-06-19 change in relief Authority/Any Paid or Sl. No Taluk Village Name of disaster affected Address of the Disaster Affected Number column as ‘Nil’) (Yes/No) (Yes/No) (Yes/No) amount) other reason) Not Paid 1 Kozhenchery mallppuzhassery suresh kumar b kalamel padinjattethil 1312025504 16-29 % Damage Approved Paid nellikunnath jyothi 2 Kozhenchery kidangannur radhamani devarajan bhabhavanam ,kurichimuttom 1312004501 16-29 % Damage Approved Paid 3 Kozhenchery kidangannur raju k k blk no 115, 1312082912 16-29 % Damage Approved Paid 4 Kozhenchery Pathanamthitta Syamalakumari R Thiruneelamannil 1312035437 16-29 % Damage Approved Paid 5 Kozhenchery Pathanamthitta Omanakuttan N Kuzhikkathil Puthen Veedu 1312034769 16-29 % Damage Approved Paid 6 Kozhenchery Mallapuzhasseril K Dileep Kumar Krishna Kripa 1312025841 16-29 % Damage Approved Paid 7 Kozhenchery Mallappuzhaserry Manju Santhosh Kumbhamalayil 1312023063 16-29 % Damage Approved Paid 8 Kozhenchery Mallappuzhaserry Pushpakumari G Perumpallil 1312025417 16-29 % Damage Approved Paid 9 Kozhenchery Kozhencherry Leelamma Nebu Nebu Villa 1312081698 16-29 % Damage Approved Paid 10 Kozhenchery Kozhencherry Rama Devi Vechoor Mankkal 1312095438 16-29 -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

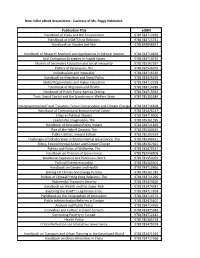

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

Accused Persons Arrested in Pathanamthitta District from 27.06.2021To03.07.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Pathanamthitta district from 27.06.2021to03.07.2021 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 THANNIMOOTTIL VEEDU PATHANA 03-07-2021 961/2021 SHAHUL 42, KULASEKHARAPA KULASEKHA MTHITTA JHONSON.K BAILED BY 1 ANSARI at 12:35 U/s 118(a) of HAMEED Male THY RAPATHY (pathanamth SI OF POLICE POLICE Hrs KP Act PATHANAMTHITT itta) A Moolakkal 960/2021 PATHANA purayidom veedu, 03-07-2021 Ramesh Muhammad 35, Azhoor U/s 279 IPC MTHITTA BAILED BY 2 Shajahan Anappara, at 10:35 Kumar, SI of ali Male junction & 3(1) r/w (pathanamth POLICE Kumbazha, Hrs Police 181 MV Act itta) Pathanamthitta. Karuveli PATHANA 03-07-2021 Ramesh 28, colony,vadakkemuri 957/2021 MTHITTA BAILED BY 3 PRAVEEN Prasanth Central jn at 08:30 Kumar, SI of Male ,udayanapuram, U/s 279 IPC (pathanamth POLICE Hrs Police Kottayam. itta) Chennirkkara 954/2021 PATHANA 02-07-2021 Ramesh 20, villege, unnukal, U/s 279 IPC MTHITTA BAILED BY 4 Joji Jose Kaipattur at 13:57 Kumar, SI of Male valuthara, mukalil & 3(1) r/w (pathanamth POLICE Hrs Police puthanveedu 181 MV Act itta) PATHANA Olickal veedu 01-07-2021 54, 942/2021 MTHITTA Vijayan, SI of BAILED BY 5 Mohanan Raghavan myladumpara Kumbazha at 11:00 Male U/s 279 IPC (pathanamth Police POLICE kumbazha pta Hrs itta) Kuzhiyathethil PATHANA House , police 30-06-2021 939/2021 Subrahamny 36, KannanKara MTHITTA Sanju Joseph, BAILED BY 6 Sharath Headquarters , at 18:10 U/s 118(a) of am Male party office (pathanamth SI of Police POLICE Traffic Enforcement Hrs KP Act itta) . -

Televangelism and the Changing Habits of Worshippers in Nairobi

TELEVANGELISM AND THE CHANGING HABITS OF WORSHIPPERS IN NAIROBI COUNTY ESTHER NYABOKE MOKAYA A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PART FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN COMMUNICATION STUDIES IN THE SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI 2015 DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university for any other award Signature………………………………… Date………………………… Esther Nyaboke Mokaya B.Ed (Arts) REG NO: K50/70018/2013 This research project has been submitted to the School of Journalism and Media Studies, University of Nairobi for examination with my approval as a University Supervisor Supervisor`s Signature…………………… Date……………………..… Dr. Ndeti Ndati School of Journalism and Media Studies University of Nairobi i DEDICATION I dedicate this project to my husband Forah and daughter Taraji for their support and encouragement during the writing of this project. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to thank my supervisor Dr Ndeti Ndati and my colleagues for their invaluable support and comments which went a long way in putting together this research project. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION....................................................................................................................... i DEDICATION.......................................................................................................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..................................................................................................... -

Download a Pdf File of This Issue for Free Download

CHRISTIAN HISTORY Issue 102 People of Faith How America’s many churches shaped “one nation under God.” IFC_POFad_CHM102_CHM102 4/27/12 10:28 AM Page 1 Survey the history of Christianity in America from before the Pilgrims to the present in this stunning DVD series. You’ll gain valuable perspective on the people and ideas that shaped America and see how it came to be the first nation in history based upon the ideal of religious liberty. In this six-episode series you’ll meet the spiritual visionaries, leaders, and entrepreneurs who shaped Christianity across the centuries and dramatically influenced the culture we live in today, including Jonathan Edwards, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Billy Graham among many others. Learn about the key events, movements, and controversies that continue to shape us today such as the Great Awakening, the abolitionist movement, 19th-century Catholic immigration, the Prohibition era, modernism and $ 99 fundamentalism, and the social gospel, civil rights, and pro-life 29. #501437D movements, and more. Well researched, balanced, fast paced, and insightful, People of Faith features expert commentary from an array of scholars such as Martin Marty, Mark Noll, Thomas Kidd, Kathryn Long, and many others. Produced and created by the Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals at Wheaton College, this amazing resource will help you discover the importance of Christian history as we consider the future of the church in America. The two-DVD set includes • six half-hour segments, • study and discussion questions, • script transcripts, • additional interviews with scholars, and • optional English subtitles. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Pathanamthitta District from 07.09.2014 to 13.09.2014

Accused Persons arrested in Pathanamthitta district from 07.09.2014 to 13.09.2014 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, Rank which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Pulluvila Vadakkethil Assankalungu Pandalam 12.09.14- Cr. 1305/14 U/s SI. Sri. R. 1 Jose Antony Male- 52 Pandalam JFMC, Adoor Nooranadu P.O Pvt. Bus stand 11.00 hrs 118(a) of KP Act Bhaskaran Palamel village Sivavilasam Veedu, Near 640/2014 u/s 12.09.14 K.S Vijayan , 2 Sathayan Chellappan Nair 64, Male Aquaduct Vazhappara, Kalanjoor 20(b)(ii)(A) Koodal JFMC-1 Adoor 15.00 SHO koodal Kalanjoor Village NDPS Act Cr. 1830/14, U/s AIMO STATE, 01/09/14 420, 120(b0, 34 KS Gopakumar 3 JOSHUA JOHNY 26/M UMURUEKWE BANGALURU Adoor JFMC, Adoor 21.30 IPC & 66(D) of SIO of Police VILLAGE, NIGERIA IT Act OWERRI AKABO, Cr. 1830/14, U/s MICHEAL AMUKACHI, 01/09/14 420, 120(b0, 34 KS Gopakumar 4 MARK CHIKODI 24/M IKEDURU LOCAL BANGALURU Adoor JFMC, Adoor 21.45 IPC & 66(D) of SIO of Police UNAKA GOVERNMENT, IT Act NIGERIA NO. 33, 14TH ROAD, Cr. 1830/14, U/s OBEDIEBO 1ST AVENUE, 01/09/14 420, 120(b0, 34 KS Gopakumar 5 OKAFOR 24/M BANGALURU Adoor JFMC, Adoor UCHE GWARIUPA, ABUJA, 21.55 IPC & 66(D) of SIO of Police NIGERIA IT Act Cr. -

Abstract Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, Anti

ABSTRACT KAMALADEVI CHATTOPADHYAYA, ANTI-IMPERIALIST AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS ACTIVIST, 1939-41 by Julie Laut Barbieri This paper utilizes biographies, correspondence, and newspapers to document and analyze the Indian socialist and women’s rights activist Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya’s (1903-1986) June 1939-November 1941 world tour. Kamaladevi’s radical stance on the nationalist cause, birth control, and women’s rights led Gandhi to block her ascension within the Indian National Congress leadership, partially contributing to her decision to leave in 1939. In Europe to attend several international women’s conferences, Kamaladevi then spent eighteen months in the U.S. visiting luminaries such as Eleanor Roosevelt and Margaret Sanger, lecturing on politics in India, and observing numerous social reform programs. This paper argues that Kamaladevi’s experience within Congress throughout the 1930s demonstrates the importance of gender in Indian nationalist politics; that her critique of Western “international” women’s organizations must be acknowledged as a precursor to the politics of modern third world feminism; and finally, Kamaladevi is one of the twentieth century’s truly global historical agents. KAMALADEVI CHATTOPADHYAYA, ANTI-IMPERIALIST AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS ACTIVIST, 1939-41 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History By Julie Laut Barbieri Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2008 Advisor____________________________ (Judith P. Zinsser) Reader_____________________________ (Mary E. Frederickson) Reader_____________________________ (David M. Fahey) © Julie Laut Barbieri 2008 For Julian and Celia who inspire me to live a purposeful life. Acknowledgements March 2003 was an eventful month. While my husband was in Seattle at a monthly graduate school session, I discovered I was pregnant with my second child.