Download a Pdf File of This Issue for Free Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Churches in Greater Los Angeles

Churches in Greater Los Angeles Church Lists are updated quarterly (Jan-Apr-July-Oct) African Methodist Episcopal (See Methodist) Anglican (See Episcopal) Apostolic 2nd Apostolic Church of Long Beach 2200 E Pac Coast Hwy (562) 434-3570,Long Beach Alpha Omega Apostolic Church 9527 S Main St, (323) 777-9579, Los Angeles 90003 https://www.facebook.com/pages/Alpha-Omega-Apostolic-Church/160004754021197 Apostolic Ark Faith Assembly 10420 Palms Blvd, (310) 558-9271, Los Angeles 90064 Apostolic Assembly 1328 E Florence Ave, (323) 582-3383, Los Angeles 90001 https://www.facebook.com/pages/1328-E-Florence-Ave-90001/183287175181411 Apostolic Assembly 235 N San Gabriel Ave (626) 815-0319,Azusa Apostolic Assembly 872 N Brand Blvd (818) 361-6000,San Fernando Apostolic Assembly Iglesia Apostolica 1237 Sepulveda Blvd (310) 539-7027,Torrance Apostolic Bethel Temple 1708 E Carson St (310) 513-9307,Carson Apostolic Christian 701 S 4th Ave (626) 330-5425,La Puente Apostolic Christian Church of Altadena 736 E Calaveras St (626) 798-5214,Altadena Apostolic Christian Church of Pasadena 434 N Altadena Dr (626) 795-8514,Pasadena Apostolic Christian Fellowship 7601 Crenshaw Blvd (323) 971-0791,Los Angeles Apostolic Church 11921 Saticoy St (818) 982-6883,North Hollywood Apostolic Church 3936 Cogswell Rd (626) 442-3455,El Monte Apostolic Church 9312 Alondra Blvd (562) 866-8222,Bellflower Apostolic Church 2450 Griffin Ave, (323) 441-1698, Los Angeles 90031 Apostolic Church 701 S Ferris Ave, (323) 262-7917, Los Angeles 90022 Apostolic Church of Whittier 5724 Esperanza -

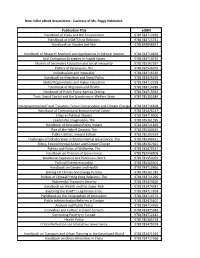

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

Appendix B. Scoping Report

Appendix B. Scoping Report VALERO CRUDE BY RAIL PROJECT Scoping Report Prepared for November 2013 City of Benicia VALERO CRUDE BY RAIL PROJECT Scoping Report Prepared for November 2013 City of Benicia 550 Kearny Street Suite 800 San Francisco, CA 94104 415.896.5900 www.esassoc.com Los Angeles Oakland Olympia Petaluma Portland Sacramento San Diego Seattle Tampa Woodland Hills 202115.01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Valero Crude By Rail Project Scoping Report Page 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 2. Description of the Project ........................................................................................... 2 Project Summary ........................................................................................................... 2 3. Opportunities for Public Comment ............................................................................ 2 Notification ..................................................................................................................... 2 Public Scoping Meeting ................................................................................................. 3 4. Summary of Scoping Comments ................................................................................ 3 Commenting Parties ...................................................................................................... 3 Comments Received During the Scoping Process ........................................................ 4 Appendices -

Televangelism and the Changing Habits of Worshippers in Nairobi

TELEVANGELISM AND THE CHANGING HABITS OF WORSHIPPERS IN NAIROBI COUNTY ESTHER NYABOKE MOKAYA A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PART FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN COMMUNICATION STUDIES IN THE SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI 2015 DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university for any other award Signature………………………………… Date………………………… Esther Nyaboke Mokaya B.Ed (Arts) REG NO: K50/70018/2013 This research project has been submitted to the School of Journalism and Media Studies, University of Nairobi for examination with my approval as a University Supervisor Supervisor`s Signature…………………… Date……………………..… Dr. Ndeti Ndati School of Journalism and Media Studies University of Nairobi i DEDICATION I dedicate this project to my husband Forah and daughter Taraji for their support and encouragement during the writing of this project. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to thank my supervisor Dr Ndeti Ndati and my colleagues for their invaluable support and comments which went a long way in putting together this research project. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION....................................................................................................................... i DEDICATION.......................................................................................................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..................................................................................................... -

The Pneumatic Experiences of the Indian Neocharismatics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE PNEUMATIC EXPERIENCES OF THE INDIAN NEOCHARISMATICS By JOY T. SAMUEL A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham June 2018 i University of Birmingham Research e-thesis repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and /or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any success or legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. i The Abstract of the Thesis This thesis elucidates the Spirit practices of Neocharismatic movements in India. Ever since the appearance of Charismatic movements, the Spirit theology has developed as a distinct kind of popular theology. The Neocharismatic movement in India developed within the last twenty years recapitulates Pentecostal nature spirituality with contextual applications. Pentecostalism has broadened itself accommodating all churches as widely diverse as healing emphasized, prosperity oriented free independent churches. Therefore, this study aims to analyse the Neocharismatic churches in Kerala, India; its relationship to Indian Pentecostalism and compares the Sprit practices. It is argued that the pneumatology practiced by the Neocharismatics in Kerala, is closely connected to the spirituality experienced by the Indian Pentecostals. -

Civil Rights History Project

The Reverend Joseph Lowery Interview, 6-6-11 Page 1 of 26 Civil Rights History Project Interview completed by the Southern Oral History Program under contract to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History & Culture and the Library of Congress, 2011 Interviewee: The Reverend Joseph E. Lowery Interview Date: June 6, 2011 Location: Sanctuary of Cascade United Methodist Church, Atlanta, Georgia Interviewer: Joseph Mosnier, Ph.D. Videographer: John Bishop Length: 1:02:49 Special Note: Cheryl Lowery-Osborne, Reverend Lowery’s daughter, drove him from his home to the church and stayed to watch the interview from a rear pew. John Bishop: We’re rolling. Joe Mosnier: Today is Monday, June 6, 2011. My name is Joe Mosnier of the Southern Oral History Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I am with videographer John Bishop. We are in Atlanta, Georgia, at Cascade United Methodist Church to complete an oral history interview for the Civil Rights History Project, which is a joint undertaking of the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. And we are especially privileged and very pleased today to be with Reverend Joseph Lowery. Um, Reverend Lowery, thank you so much for sitting down with us. Joseph Lowery: You’re quite welcome. You’ll get a bill in the mail. [Laughter] The Reverend Joseph Lowery Interview, 6-6-11 Page 2 of 26 JM: I thought I might, um – I thought, as we’re going to be talking here today mostly about, I think, the ’50s and ’60s, um, and then a little bit, um, a little bit – a few questions thereafter, mostly ’50s and ’60s. -

March on Washington Summary

March On Washington Summary In late 1962, civil rights activists started to organize what would become the largest civil rights demonstration in the history of the United States. It took a while, but by June of 1963, they had put together an impressive group of leaders and speakers – including King – to help them. The full name of the march was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and its organizers had to make sure people had a way of getting into the city. They had to make sure marchers knew where to go and what to do once they got there. They had to have doctors and nurses in case anyone needed first aid. They had to provide water, security, and be ready for any emergency. And they needed some way to pay for all of it. It was going to take fund raising, planning and lots of work. On Aug. 28, the city swelled with marchers. They drove in. They bussed in. They took trains. Three student marchers walked and hitchhiked 700 miles to get there. A quarter million people waved signs and cheered and listened to speakers address the civil rights problems challenging America. The last speaker was Martin Luther King Jr. “I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation,” King began. And it did; the March on Washington is still the largest political rally in our nation’s history. The march was an unprecedented success. More than 200,000 black and white Americans shared a joyous day of speeches, songs, and prayers led by a celebrated array of clergymen, civil rights leaders, politicians, and entertainers. -

Commodification of Religion Through Televangelism a Rhetorical Analysis

COMMODIFICATION OF RELIGION THROUGH TELEVANGELISM: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF SELECTED CHARISMATIC PROGRAMMES IN KENYA PATRICK MUTURI KARANJA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication of Egerton University EGERTON UNIVERSITY OCTOBER 2019 DECLARATION AND RECOMMENDATION Declaration This Thesis is my original work and has not been submitted in its current form to this or any other University for the award of a degree to the best of my knowledge. Signature: ---------------------------------- Date: ---------------------------------- Patrick Muturi Karanja AM19/33627/14 Recommendation We wish to confirm that this thesis was prepared under our supervision and is recommendation for presentation and examination at Egerton University. Signature---------------------------------- Date: ---------------------------------- Dr Josphine Khaemba Department of Literature, Languages and Linguistics Egerton University. Signature--------------------------------- Date: ---------------------------------- Mr. Sammy Gachigua Department of Literature, Languages and Linguistics Egerton University. ii COPYRIGHT © 2019 Patrick Muturi Karanja All rights are reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted in any form or means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise without prior permission of the author or Egerton University on behalf of the author. iii DEDICATION I dedicate this study to my family: my wife and children, for their prayers and continuous encouragement. Their presence around me was a source of much inspiration which guaranteed stability of mind and soul, for the accomplishment of this arduous task. For their love and understanding, I will forever be grateful. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENT First and foremost I wish to thank the Almighty God for giving me the grace and ability to accomplish this study. -

1 0 a B C D E 2 3

0 A B C D E SANTA ROSA ST. ROSA SANTA WHEATON SYMBOL KEY HARRISON AVE. COLLEGE Admissions (Undergraduate) MAP Handicap Accessible Visitor Parking IRVING AVE. IRVING Parking for Grammar Fischer Hall Houses School GRAMMAR SCHOOL DR. ST. HOWARD OAK AVE. Outreach 1 House Lawson Field IRVING AVE. IRVING Hearth NORTH PATH House CENTENNIAL ST. CENTENNIAL FOREST AVE. ST. ROSA SANTA LeBar Phoenix Tennis Courts House House JEFFERSON AVE. Irving House Kilby Country Fine Arts International House House House House Teresa House Hunter House Traber AVE. WEBSTER Hall KENILWORTH AVE. Kay Sports & House 2 Recreation Marion E. Armerding Hall Complex Wade Center Fellowship House Smith Hall LINCOLN AVE. Evans Buswell Wyngarden Hall Mathetai Memorial House Library Edman UNIVERSITY PLACE Memorial McManis Hall Chapel Saint and Elliot Harbor Residential Complex Quad House Science Center Schell Hall Chase Commons Edman FRANKLIN ST. Plaza Jenks Hall Pierce Soderquist Todd M. Memorial Plaza 3 Chapel Adams Memorial Beamer Hall Student Student Center Center HOWARD ST. HOWARD White Student Leedy Soball House McAlister Services Field Conservatory Williston Hall Building WASHINGTON ST. WASHINGTON 916 UNION AVE. Blanchard Hall College Chase House 904 814 818 College 802 College College Westgate COLLEGE AVE. College 602 Chase ST. PRESIDENT Bean Stadium Chase Service Center 4 McCully Stadium SEMINARY AVE. COLLEGE AVE. CHASE ST. Graham House Billy Graham Center Terrace Apartments CRESCENT BLVD. Crescent Apartments Campus Utility Chicago and Northwestern Railroad 5 AVE. STODDARD Michigan Apartments COLLEGE AVE. MICHIGAN ST. v CAMPUS LOCATIONS CAMPUS HOUSING Adams Hall (A-3) Leedy Softball Field (C-3) Student Services Building (B-3) Chase House (C-4) International House (C-2) Admissions (Undergraduate) Armerding Hall (B-2) Marion E. -

1 Steven H. Hobbs1 I Plucked My

INTRODUCTION ALABAMA’S MIRROR: THE PEOPLE’S CRUSADE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS Steven H. Hobbs1 I plucked my soul out of its secret place, And held it to the mirror of my eye To see it like a star against the sky, A twitching body quivering in space, A spark of passion shining on my face. from I Know by Soul, by Claude McKay2 On April 4, 2014, The University of Alabama School of Law hosted a symposium on the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The papers presented at that symposium are included in this issue of the Alabama Civil Rights & Civil Liberties Law Review. The symposium was an opportunity to reflect on the reasons and history behind the Act, its implementation to make real the promises of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, and the continuing urgency to make the principles of the Act a reality. We, in essence, plucked out the soul of our constitutional democracy’s guarantee of equality under the law and held it up for self-reflection. In introducing the symposium, I note the description that appeared in the program stating the hope for the event: This symposium is a commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The passage of the Act marked the beginning of a new era of American public life. At the time it was enacted, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was perceived by many to be the codified culmination of decades of 1 Tom Bevill Chairholder of Law, University of Alabama School of Law. -

JEWS and the CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

ENTREE: A PICTURE WORTH A THOUSAND NARRATIVES JEWS and the FRAMING A picture may be worth a thousand words, but it’s often never quite as CIVIL RIGHTS simple as it seems. Begin by viewing the photo below and discussing some of the questions that follow. We recommend sharing more MOVEMENT background on the photo after an initial discussion. APPETIZER: RACIAL JUSTICE JOURNEY INSTRUCTIONS Begin by reflecting on the following two questions. When and how did you first become aware of race? Think about your family, where you lived growing up, who your friends were, your viewing of media, or different models of leadership. Where are you coming from in your racial justice journey? Please share one or two brief experiences. Photo Courtesy: Associated Press Once you’ve had a moment to reflect, share your thoughts around the table with the other guests. GUIDING QUESTIONS 1. What and whom do you see in this photograph? Whom do you recognize, if anyone? 2. If you’ve seen this photograph before, where and when have you seen it? What was your reaction to it? 3. What feelings does this photograph evoke for you? 01 JEWS and the CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT BACKGROUND ON THE PHOTO INSTRUCTIONS This photograph was taken on March 21, 1965 as the Read the following texts that challenge and complicate the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. marched with others from photograph and these narratives. Afterwards, find a chevruta (a Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in support of voting partner) and select several of the texts to think about together. -

CATALOG Table of Contents

• • • 2012-2013 CATALOG Table of Contents Wheaton in Profile .................................................................................................................. 1 Undergraduate Student Life ................................................................................................... 17 Undergraduate Admissions ................................................................................................... 29 Undergraduate Academic Policies and Information ................................................................... 36 Special Programs ................................................................................................................. 58 Arts and Sciences Programs .................................................................................................. 68 Conservatory of Music ......................................................................................................... 195 Graduate Academic Policies and Information ......................................................................... 230 Graduate Programs ............................................................................................................ 253 Financial Information ........................................................................................................ 302 Directory ......................................................................................................................... 328 College Calendar ...............................................................................................................