Televangelism and the Changing Habits of Worshippers in Nairobi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

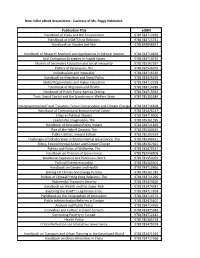

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

Download a Pdf File of This Issue for Free Download

CHRISTIAN HISTORY Issue 102 People of Faith How America’s many churches shaped “one nation under God.” IFC_POFad_CHM102_CHM102 4/27/12 10:28 AM Page 1 Survey the history of Christianity in America from before the Pilgrims to the present in this stunning DVD series. You’ll gain valuable perspective on the people and ideas that shaped America and see how it came to be the first nation in history based upon the ideal of religious liberty. In this six-episode series you’ll meet the spiritual visionaries, leaders, and entrepreneurs who shaped Christianity across the centuries and dramatically influenced the culture we live in today, including Jonathan Edwards, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Billy Graham among many others. Learn about the key events, movements, and controversies that continue to shape us today such as the Great Awakening, the abolitionist movement, 19th-century Catholic immigration, the Prohibition era, modernism and $ 99 fundamentalism, and the social gospel, civil rights, and pro-life 29. #501437D movements, and more. Well researched, balanced, fast paced, and insightful, People of Faith features expert commentary from an array of scholars such as Martin Marty, Mark Noll, Thomas Kidd, Kathryn Long, and many others. Produced and created by the Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals at Wheaton College, this amazing resource will help you discover the importance of Christian history as we consider the future of the church in America. The two-DVD set includes • six half-hour segments, • study and discussion questions, • script transcripts, • additional interviews with scholars, and • optional English subtitles. -

The Pneumatic Experiences of the Indian Neocharismatics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE PNEUMATIC EXPERIENCES OF THE INDIAN NEOCHARISMATICS By JOY T. SAMUEL A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham June 2018 i University of Birmingham Research e-thesis repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and /or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any success or legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. i The Abstract of the Thesis This thesis elucidates the Spirit practices of Neocharismatic movements in India. Ever since the appearance of Charismatic movements, the Spirit theology has developed as a distinct kind of popular theology. The Neocharismatic movement in India developed within the last twenty years recapitulates Pentecostal nature spirituality with contextual applications. Pentecostalism has broadened itself accommodating all churches as widely diverse as healing emphasized, prosperity oriented free independent churches. Therefore, this study aims to analyse the Neocharismatic churches in Kerala, India; its relationship to Indian Pentecostalism and compares the Sprit practices. It is argued that the pneumatology practiced by the Neocharismatics in Kerala, is closely connected to the spirituality experienced by the Indian Pentecostals. -

Commodification of Religion Through Televangelism a Rhetorical Analysis

COMMODIFICATION OF RELIGION THROUGH TELEVANGELISM: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF SELECTED CHARISMATIC PROGRAMMES IN KENYA PATRICK MUTURI KARANJA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication of Egerton University EGERTON UNIVERSITY OCTOBER 2019 DECLARATION AND RECOMMENDATION Declaration This Thesis is my original work and has not been submitted in its current form to this or any other University for the award of a degree to the best of my knowledge. Signature: ---------------------------------- Date: ---------------------------------- Patrick Muturi Karanja AM19/33627/14 Recommendation We wish to confirm that this thesis was prepared under our supervision and is recommendation for presentation and examination at Egerton University. Signature---------------------------------- Date: ---------------------------------- Dr Josphine Khaemba Department of Literature, Languages and Linguistics Egerton University. Signature--------------------------------- Date: ---------------------------------- Mr. Sammy Gachigua Department of Literature, Languages and Linguistics Egerton University. ii COPYRIGHT © 2019 Patrick Muturi Karanja All rights are reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted in any form or means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise without prior permission of the author or Egerton University on behalf of the author. iii DEDICATION I dedicate this study to my family: my wife and children, for their prayers and continuous encouragement. Their presence around me was a source of much inspiration which guaranteed stability of mind and soul, for the accomplishment of this arduous task. For their love and understanding, I will forever be grateful. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENT First and foremost I wish to thank the Almighty God for giving me the grace and ability to accomplish this study. -

The Crystal Cathedral Was a Monument to Televangelism. It's About to Become a Catholic Church

The Washington Post Religion Analysis The Crystal Cathedral was a monument to televangelism. It’s about to become a Catholic church. By Mary Louise Schumacher July 17 What happens when an icon of feel-good theology and California kitsch gets born again as a Catholic church? For years, Christians, Southern Californians and design devotees alike have anticipated the resurrection of the Crystal Cathedral, the Orange County church designed by modernist architect Philip Johnson. It was the home of televangelist Robert Schuller and his “Hour of Power” TV program, watched in its heyday by tens of millions, in 156 countries. Touted as the largest glass building in the world when it opened in 1980, the megachurch was purchased by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange in 2012, thanks to a messy bankruptcy. The diocese renamed it Christ Cathedral and, in fact, acquired the whole architecturally significant campus, including buildings by Richard Neutra and Richard Meier. It’s not every day that the Roman Catholic Church occupies a New Age monument, and the unorthodox pairing provokes certain questions. Could the glitzy building, countercultural in its way, be a fitting home for a faith rooted in tradition? Is Schuller’s house of “Possibility Thinking” an apt home for the Sorrowful Mysteries? (The former is the name the late televangelist gave for his affirming worldview, and the latter is a group of Catholic meditations on suffering.) “It does feel like a weird marriage,” says Alexandra Lange, an architecture critic for Curbed. There’s something “New Age-y” and “kitschy and cheery” about the cathedral that seems at odds with the “formality and sternness” associated with many Catholic buildings, says Dallas Morning News architecture critic Mark Lamster, who wrote a biography of Johnson. -

Preaching to the Converted: Making Responsible Evangelical Subjects Through Media by Holly Thomas a Thesis Submitted to the Facu

Preaching to the Converted: Making Responsible Evangelical Subjects Through Media By Holly Thomas A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016, Holly Thomas Abstract This dissertation examines contemporary televangelist discourses in order to better articulate prevailing models of what constitutes ideal-type evangelical subjectivities and televangelist participation in an increasingly mediated religious landscape. My interest lies in apocalyptic belief systems that engage end time scenarios to inform understandings of salvation. Using a Foucauldian inspired theoretical-methodology shaped by discourse analysis, archaeology, and genealogy, I examine three popular American evangelists who represent a diverse array of programming content: Pat Robertson of the 700 Club, John Hagee of John Hagee Today, and Jack and Rexella Van Impe of Jack Van Impe Presents. I argue that contemporary evangelical media packages now cut across a variety of traditional and new technologies to create a seamless mediated empire of participatory salvation where believers have access to complementary evangelist products and messages twenty-four hours a day from a multitude of access points. For these reasons, I now refer to televangelism as mediated evangelism and televangelists as mediated evangelists while acknowledging that the televised programs still form the cornerstone of their mediated messages and engagement with believers. The discursive formations that take shape through this landscape of mediated evangelism contribute to an apocalyptically informed religious-political subjectivity that identifies civic and political engagement as an expected active choice and responsibility for attaining salvation, in line with other more obviously evangelical religious practices, like prayer, repentance, and acceptance of Jesus Christ as savior. -

Televangelists, Media Du'ā, and 'Ulamā'

TELEVANGELISTS, MEDIA DU‘Ā, AND ‘ULAMĀ’: THE EVOLUTION OF RELIGIOUS AUTHORITY IN MODERN ISLAM A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Islamic Studies By Tuve Buchmann Floden, M.A. Washington, DC August 23, 2016 Copyright 2016 by Tuve Buchmann Floden All Rights Reserved ii TELEVANGELISTS, MEDIA DU‘Ā, AND ‘ULAMĀ’: THE EVOLUTION OF RELIGIOUS AUTHORITY IN MODERN ISLAM Tuve Buchmann Floden, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Felicitas M. Opwis, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The rise of modern media has led to debates about religious authority in Islam, questioning whether it is fragmenting or proliferating, and exploring the state of the ‘ulamā’ and new groups like religious intellectuals and Muslim televangelists. This study explores these changes through a specific group of popular preachers, the media du‘ā, who are characterized by their educational degrees and their place outside the religious establishment, their informal language and style, and their extensive use of modern media tools. Three media du‘ā from the Arab world are the subject of this study: Amr Khaled, Ahmad al-Shugairi, and Tariq al- Suwaidan. Their written material – books, published interviews, social media, and websites – form the primary sources for this work, supplemented by examples from their television programs. To paint a complete picture, this dissertation examines not only the style of these preachers, but also their goals, their audience, the topics they address, and their influences and critics. This study first compares the media du‘ā to Christian televangelists, revealing that religious authority in Islam is both proliferating and differentiating, and that these preachers are subtly influencing society and politics. -

The Media in Society: Religious Radio Stations, Socio-Religious Discourse and National Cohesion in Tanzania

The Media in Society: Religious Radio Stations, Socio-Religious Discourse and National Cohesion in Tanzania By Francis Xavier Ng’atigwa Dissertation submitted to Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS) and the Department of Media Studies, Bayreuth University in the Partial fulfillment of the requirements for Doctor of Philosophy in Media Studies Supervisor Prof. Dr. Jürgen E. Müller Bayreuth, 11 November 2013 Dedication In memory of Bernard and Juliana, the finest! i Acknowledgements This doctoral thesis is a result of combined efforts of individuals and institutions. I wish to thank all who kindly helped me to realize it. Foremost I acknowledge the immeasurable guidance, advice and constant academic support from the Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS) mentoring team: Drs. Franz Kogelmann, Asonzeh Ukah and Bernadin Mfumbusa which made the realization of this study possible. In a very special way I extend my heartfelt thanks to Dr. Franz Kogelmann who introduced St. Augustine University of Tanzania to Bayreuth University. Through his efforts I was able to join BIGSAS. Equally my sincere appreciation goes to Bishop Dr. Bernardin Mfumbusa who encouraged me to study media and has been invaluable on both academic and personal levels, for which I am very grateful. I would like to seize the opportunity to express my sincere gratitude and recognition to Prof. Dr. Jürgen E. Müller for accepting to be the final supervisor of this study. My deep appreciation goes to him and his kind way of handling my issue. The scholarship that has allowed me to study at BIGSAS was secured through the “Staff Development Funds” of St. -

ABSTRACT “SHALOM, GOD BLESS, and PLEASE EXIT to the RIGHT:” a CULTURAL ETHNOGRAPHY of the HOLY LAND EXPERIENCE. by Stephanie

ABSTRACT “SHALOM, GOD BLESS, AND PLEASE EXIT TO THE RIGHT:” A CULTURAL ETHNOGRAPHY OF THE HOLY LAND EXPERIENCE. by Stephanie Nicole Brehm This thesis explores the intersection of evangelical Christianity, entertainment, and consumerism in America through a cultural ethnography of the Holy Land Experience theme park in Orlando, Florida. This case study examines the diversity within the evangelical subculture and the blurring of the line between sacred and secular in American popular culture. In this thesis, I begin by discussing the historical lineage of American evangelical entertainment and consumerism, as well as disneyfication theories. I then classify the Holy Land Experience as a contemporary form of disneyfied evangetainment. Finally, I delve into the implications of classifying this theme park as a sacred space, a pilgrimage, or a replica, and I explore the types of worship and material objects sold and purchased at the Holy Land Experience. “SHALOM, GOD BLESS, AND PLEASE EXIT TO THE RIGHT:” A CULTURAL ETHNOGRAPHY OF THE HOLY LAND EXPERIENCE. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Comparative Religion by Stephanie Nicole Brehm Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2011 Advisor_______________________________________ (Dr. Peter W. Williams) Reader_______________________________________ (Dr. James S. Bielo) Reader_______________________________________ (Dr. James C. Hanges) TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................... -

African Initiated Christianity and the Decolonisation of Development

African Initiated Christianity and the Decolonisation of Development This book investigates the substantial and growing contribution which African Independent and Pentecostal Churches are making to sustainable development in all its manifold forms. Moreover, this volume seeks to elucidate how these churches reshape the very notion of sustainable development and contribute to the decolonisation of development. Fostering both overarching and comparative perspectives, the book includes chapters on West Africa (Nigeria, Ghana, and Burkina Faso) and Southern Africa (Zimbabwe and South Africa). It aims to open up a subfield focused on African Initiated Christianity within the religion and development discourse, substantially broadening the scope of the existing literature. Written predominantly by scholars from the African continent, the chapters in this volume illuminate potentials and perspectives of African Initiated Christianity, combining theoretical contributions, essays by renowned church leaders, and case studies focusing on particular churches or regional contexts. While the contributions in this book focus on the African continent, the notion of development underlying the concept of the volume is deliberately wide and multidimensional, covering economic, social, ecological, political, and cultural dimensions. Therefore, the book will be useful for the community of scholars interested in religion and development as well as researchers within African studies, anthropology, development studies, political science, religious studies, sociology of religion, and theology. It will also be a key resource for development policymakers and practitioners. Philipp Öhlmann is Head of the Research Programme on Religious Com- munities and Sustainable Development, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, and Research Associate, University of Pretoria, South Africa. Wilhelm Gräb is Head of the Research Programme on Religious Communities and Sustainable Development, Humboldt- Universität zu Berlin, and Extra- ordinary Professor, Stellenbosch University, South Africa. -

Televangelism and the Socio-Political Mobilization of Pentecostals in Port Harcourt Metropolis: a Kap Survey

Godwin Okon1 Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Оригинални научни рад Port Harcourt, Nigeria UDK: 279.125(669) ; 316.77:2-475(669) TELEVANGELISM AND THE SOCIO-POLITICAL MOBILIZATION OF PENTECOSTALS IN PORT HARCOURT METROPOLIS: A KAP SURVEY Abstract This study was borne out of the need to ascertain the extent to which televangelists in Port Harcourt; deploy media content towards issues that border on socio-political development. The primary objective was to empirically determine if a correspondence exists between advocacy by televangelists and compliance by Pentecostals as mani- fested in Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP). The study necessitated triangulation with the Weighted Mean Score (WMS) as the basis for quantitative analysis. Findings revealed televangelism to revolve around the pastor (p), message (m) and church (c). Though an association link was found between ideologies expressed by televange- lists and adoption by Pentecostals, this link only found expression in the concepts of secularism and fundamentalism. Survey also revealed a dismal rating of televangelism as regards socio-political mobilization. The chi-square test showed the x2 computed to be greater than the x2 critical thus showing a disconnect between knowledge on the potential benefits of televangelism and the deployment of such benefits towards socio-economic mobilization by televangelists. It was therefore recommended that televangelism should not be used for self aggrandizement and church growth but should complement the socio-political mobilization process. It was further recom- mended that a policy framework should be put in place to ensure compliance by tel- evangelists. Key words: Mobilization, Pentecostal, Socio-Political, Televangelism, Televange- list. -

Liberty University School of Divinity

Liberty University School of Divinity The Utilization of the Internet in the Advancement of Discipleship in the Traditional Black Church A Thesis Project Submitted to The Faculty of Liberty University School of Divinity in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Ministry by Marshall Williams Lynchburg, Virginia October 8, 2020 Copyright @ 2020 by Marshall Williams All Rights Reserved ii Liberty University School of Divinity Thesis Project Approval Sheet _______________________________ Michael C. Whittington, D.Min. Assistant Professor of Practical Studies Liberty University School of Divinity _______________________________ C. Fred Smith, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Theology and Biblical Studies Liberty University School of Divinity iii ABSTRACT Discipleship and technology are interrelated. Discipleship is the process of maturing in Christ through our actions, life, and words, as well as how we present ourselves to the world. This must become integral to the vitality and mission of the traditional Black Church. Technology is a resource that can assist the traditional Black Church to fulfill the Great Commission of Matthew 28:19-20. This thesis premise is supported by applied research (survey findings from pastoral leaders within the General Missionary Baptist Convention of Georgia), academic research (scholarly material from experts in the fields of theology, sociology, statistics, and church growth), and the Bible. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To God the Father, who is the source of my strength. I love You for loving me. You have truly been the difference-maker, and I am eternally grateful for your patience, love, support, and guidance. It was always You who was there when I was overwhelmed. It was You who empowered me with the fortitude to complete my education.