1 Steven H. Hobbs1 I Plucked My

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notable Alphas Fraternity Mission Statement

ALPHA PHI ALPHA NOTABLE ALPHAS FRATERNITY MISSION STATEMENT ALPHA PHI ALPHA FRATERNITY DEVELOPS LEADERS, PROMOTES BROTHERHOOD AND ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE, WHILE PROVIDING SERVICE AND ADVOCACY FOR OUR COMMUNITIES. FRATERNITY VISION STATEMENT The objectives of this Fraternity shall be: to stimulate the ambition of its members; to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the causes of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual; to encourage the highest and noblest form of manhood; and to aid down-trodden humanity in its efforts to achieve higher social, economic and intellectual status. The first two objectives- (1) to stimulate the ambition of its members and (2) to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the cause of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual-serve as the basis for the establishment of Alpha University. Table Of Contents Table of Contents THE JEWELS . .5 ACADEMIA/EDUCATORS . .6 PROFESSORS & RESEARCHERS. .8 RHODES SCHOLARS . .9 ENTERTAINMENT . 11 MUSIC . 11 FILM, TELEVISION, & THEATER . 12 GOVERNMENT/LAW/PUBLIC POLICY . 13 VICE PRESIDENTS/SUPREME COURT . 13 CABINET & CABINET LEVEL RANKS . 13 MEMBERS OF CONGRESS . 14 GOVERNORS & LT. GOVERNORS . 16 AMBASSADORS . 16 MAYORS . 17 JUDGES/LAWYERS . 19 U.S. POLITICAL & LEGAL FIGURES . 20 OFFICIALS OUTSIDE THE U.S. 21 JOURNALISM/MEDIA . 21 LITERATURE . .22 MILITARY SERVICE . 23 RELIGION . .23 SCIENCE . .24 SERVICE/SOCIAL REFORM . 25 SPORTS . .27 OLYMPICS . .27 BASKETBALL . .28 AMERICAN FOOTBALL . 29 OTHER ATHLETICS . 32 OTHER ALPHAS . .32 NOTABLE ALPHAS 3 4 ALPHA PHI ALPHA ADVISOR HANDBOOK THE FOUNDERS THE SEVEN JEWELS NAME CHAPTER NOTABILITY THE JEWELS Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; 6th Henry A. Callis Alpha General President of Alpha Phi Alpha Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; Charles H. -

Appendix B. Scoping Report

Appendix B. Scoping Report VALERO CRUDE BY RAIL PROJECT Scoping Report Prepared for November 2013 City of Benicia VALERO CRUDE BY RAIL PROJECT Scoping Report Prepared for November 2013 City of Benicia 550 Kearny Street Suite 800 San Francisco, CA 94104 415.896.5900 www.esassoc.com Los Angeles Oakland Olympia Petaluma Portland Sacramento San Diego Seattle Tampa Woodland Hills 202115.01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Valero Crude By Rail Project Scoping Report Page 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 2. Description of the Project ........................................................................................... 2 Project Summary ........................................................................................................... 2 3. Opportunities for Public Comment ............................................................................ 2 Notification ..................................................................................................................... 2 Public Scoping Meeting ................................................................................................. 3 4. Summary of Scoping Comments ................................................................................ 3 Commenting Parties ...................................................................................................... 3 Comments Received During the Scoping Process ........................................................ 4 Appendices -

Download a Pdf File of This Issue for Free Download

CHRISTIAN HISTORY Issue 102 People of Faith How America’s many churches shaped “one nation under God.” IFC_POFad_CHM102_CHM102 4/27/12 10:28 AM Page 1 Survey the history of Christianity in America from before the Pilgrims to the present in this stunning DVD series. You’ll gain valuable perspective on the people and ideas that shaped America and see how it came to be the first nation in history based upon the ideal of religious liberty. In this six-episode series you’ll meet the spiritual visionaries, leaders, and entrepreneurs who shaped Christianity across the centuries and dramatically influenced the culture we live in today, including Jonathan Edwards, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Billy Graham among many others. Learn about the key events, movements, and controversies that continue to shape us today such as the Great Awakening, the abolitionist movement, 19th-century Catholic immigration, the Prohibition era, modernism and $ 99 fundamentalism, and the social gospel, civil rights, and pro-life 29. #501437D movements, and more. Well researched, balanced, fast paced, and insightful, People of Faith features expert commentary from an array of scholars such as Martin Marty, Mark Noll, Thomas Kidd, Kathryn Long, and many others. Produced and created by the Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals at Wheaton College, this amazing resource will help you discover the importance of Christian history as we consider the future of the church in America. The two-DVD set includes • six half-hour segments, • study and discussion questions, • script transcripts, • additional interviews with scholars, and • optional English subtitles. -

Civil Rights History Project

The Reverend Joseph Lowery Interview, 6-6-11 Page 1 of 26 Civil Rights History Project Interview completed by the Southern Oral History Program under contract to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History & Culture and the Library of Congress, 2011 Interviewee: The Reverend Joseph E. Lowery Interview Date: June 6, 2011 Location: Sanctuary of Cascade United Methodist Church, Atlanta, Georgia Interviewer: Joseph Mosnier, Ph.D. Videographer: John Bishop Length: 1:02:49 Special Note: Cheryl Lowery-Osborne, Reverend Lowery’s daughter, drove him from his home to the church and stayed to watch the interview from a rear pew. John Bishop: We’re rolling. Joe Mosnier: Today is Monday, June 6, 2011. My name is Joe Mosnier of the Southern Oral History Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I am with videographer John Bishop. We are in Atlanta, Georgia, at Cascade United Methodist Church to complete an oral history interview for the Civil Rights History Project, which is a joint undertaking of the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. And we are especially privileged and very pleased today to be with Reverend Joseph Lowery. Um, Reverend Lowery, thank you so much for sitting down with us. Joseph Lowery: You’re quite welcome. You’ll get a bill in the mail. [Laughter] The Reverend Joseph Lowery Interview, 6-6-11 Page 2 of 26 JM: I thought I might, um – I thought, as we’re going to be talking here today mostly about, I think, the ’50s and ’60s, um, and then a little bit, um, a little bit – a few questions thereafter, mostly ’50s and ’60s. -

March on Washington Summary

March On Washington Summary In late 1962, civil rights activists started to organize what would become the largest civil rights demonstration in the history of the United States. It took a while, but by June of 1963, they had put together an impressive group of leaders and speakers – including King – to help them. The full name of the march was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and its organizers had to make sure people had a way of getting into the city. They had to make sure marchers knew where to go and what to do once they got there. They had to have doctors and nurses in case anyone needed first aid. They had to provide water, security, and be ready for any emergency. And they needed some way to pay for all of it. It was going to take fund raising, planning and lots of work. On Aug. 28, the city swelled with marchers. They drove in. They bussed in. They took trains. Three student marchers walked and hitchhiked 700 miles to get there. A quarter million people waved signs and cheered and listened to speakers address the civil rights problems challenging America. The last speaker was Martin Luther King Jr. “I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation,” King began. And it did; the March on Washington is still the largest political rally in our nation’s history. The march was an unprecedented success. More than 200,000 black and white Americans shared a joyous day of speeches, songs, and prayers led by a celebrated array of clergymen, civil rights leaders, politicians, and entertainers. -

By James King B.A., Samford University, 2006 M.L.I.S., University

THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES: ARCHIVAL APPROACHES TO CIVIL RIGHTS IN NORTHERN IRELAND AND THE AMERICAN SOUTH by James King B.A., Samford University, 2006 M.L.I.S., University of Alabama, 2007 M.A., Boston College, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Computing and Information in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2018 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF COMPUTING AND INFORMATION This dissertation was presented by James King It was defended on November 16, 2017 and approved by Dr. Sheila Corrall, Professor, Library and Information Science Dr. Andrew Flinn, Reader in Archival Studies and Oral History, Information Studies, University College London Dr. Alison Langmead, Associate Professor, Library and Information Science Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Richard J. Cox, Professor, Library and Information Science ii Copyright © by James King 2018 iii THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES: ARCHIVAL APPROACHES TO CIVIL RIGHTS IN NORTHERN IRELAND AND THE AMERICAN SOUTH James King, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2018 When police and counter-protesters broke up the first march of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) in August 1968, activists sang the African American spiritual, “We Shall Overcome” before disbanding. The spiritual, so closely associated with the earlier civil rights struggle in the United States, was indicative of the historical and material links shared by the movements in Northern Ireland and the American South. While these bonds have been well documented within history and media studies, the relationship between these regions’ archived materials and contemporary struggles remains largely unexplored. While some artifacts from the movements—along with the oral histories and other materials that came later—remained firmly ensconced within the archive, others have been digitally reformatted or otherwise repurposed for a range of educational, judicial, and social projects. -

The Abbhs Newsletter Alabama Bench and Ba R Historical Society

May—June 2021 THE ABBHS NEWSLETTER ALABAMA BENCH AND BA R HISTORICAL SOCIETY From The President When, in 1993, my staff and I were called upon to prepare a plan for a judicial history program for the new Judicial Building, a whole new world was opened to me. A world that I previously did not know existed. In that world, Alabama was first, not last: in that world, Alabama's first constitution was a model for the Nation; in that world, Alabama adopted the first code of ethics for lawyers in the United States which, like the 1819 Constitution, became a model for the Nation; in that world, Alabama's Supreme Court was considered "long the ranking Supreme Court in the South”; and, in that world, Alabama's court system, under the leadership of Chief Justice Howell Heflin, became the most modern in America. These facts are seldom remembered in Alabama history textbooks, yet their impact on Alabama were tremen- dous. Twenty-eight years later, we are still exploring and discovering our legal history and trying to understand where we came from, how we got there, and where we are going next. As Robert Penn Warren said, "History cannot give us a program for the future, but it can give us a fuller understanding of ourselves, and of our common humanity, so that we can better face the future." So, as a step toward this self- understanding, I invite you to join the Alabama Bench and Bar Historical Society, a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving the history of Inside This Issue: the state's judicial and legal system and to making the citizens of the state more knowledgeable about the state's courts and their place in Alabama and United States history. -

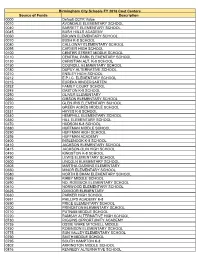

Source of Funds Description 0000 Default

Birmingham City Schools FY 2018 Cost Centers Source of Funds Description 0000 Default CCTR Value 0010 AVONDALE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0040 BARRETT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0045 BUSH HIILLS ACADEMY 0050 BROWN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0070 BUSH K-8 SCHOOL 0080 CALLOWAY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0095 CARVER HIGH SCHOOL 0100 CENTER STREET MIDDLE SCHOOL 0110 CENTRAL PARK ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0130 CHRISTIAN ALT. K-8 SCHOOL 0150 COUNCILL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0180 DUPUY ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL 0210 ENSLEY HIGH SCHOOL 0212 E.P.I.C. ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0215 EUREKA KINDERGARTEN 0232 FAMILY COURT SCHOOL 0245 GASTON K-8 SCHOOL 0250 OLIVER ELEMENTARY 0260 GIBSON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0270 GLEN IRIS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0320 GREEN ACRES MIDDLE SCHOOL 0331 HAYES K-8 SCHOOL 0340 HEMPHILL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0350 HILL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0370 HUDSON K-8 SCHOOL 0380 HUFFMAN MIDDLE SCHOOL 0390 HUFFMAN HIGH SCHOOL 0395 HUFFMAN ACADEMY 0400 INGLENOOK K-8 SCHOOL 0410 JACKSON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0415 JACKSON-OLIN HIGH SCHOOL 0450 KINGSTON K-8 SCHOOL 0490 LEWIS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0500 LINCOLN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0505 MARTHA GASKINS ELEMENTARY 0550 MINOR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0580 NORTH B BHAM ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0585 KIRBY MIDDLE SCHOOL 0590 NO. ROEBUCK ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0610 NORWOOD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0625 OXMOOR ELEMENTARY 0630 PARKER HIGH SCHOOL 0651 PHILLIPS ACADEMY K-8 0690 PRICE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0700 PRINCETON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0710 PUTNAM MIDDLE SCHOOL 0720 RAMSAY ALTERNATIVE HIGH SCHOOL 0730 RIGGINS OPPORTUNITY ACADEMY 0735 OSSIE WARE MITCHELL MIDDLE 0750 ROBINSON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0775 SUN VALLEY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0790 SMITH MIDDLE SCHOOL 0795 SOUTH HAMPTON K-8 0802 ARRINGTON MIDDLE SCHOOL 0816 KENNEDY ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL 0830 TUGGLE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 0850 WASHINGTON K-8 SCHOOL 0857 JONES VALLEY MIDDLE SCHOOL 0858 WENONAH HIGH SCHOOL 0880 WEST END ACADEMY 0890 WHATLEY K-8 SCHOOL 0900 WILKERSON MIDDLE SCHOOL 0920 WOODLAWN HIGH SCHOOL 0930 WYLAM K-8 SCHOOL 1110 SUMMER SCHOOL CENTRAL PARK 7001 EASTERN AREA CROSSING GUARDS 7002 WESTERN AREA CROSSING GUARDS 8100 INSTRUCTION POOLED COST CENTER 8102 INSTRUCTIONAL BROADCAST SERV. -

JEWS and the CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

ENTREE: A PICTURE WORTH A THOUSAND NARRATIVES JEWS and the FRAMING A picture may be worth a thousand words, but it’s often never quite as CIVIL RIGHTS simple as it seems. Begin by viewing the photo below and discussing some of the questions that follow. We recommend sharing more MOVEMENT background on the photo after an initial discussion. APPETIZER: RACIAL JUSTICE JOURNEY INSTRUCTIONS Begin by reflecting on the following two questions. When and how did you first become aware of race? Think about your family, where you lived growing up, who your friends were, your viewing of media, or different models of leadership. Where are you coming from in your racial justice journey? Please share one or two brief experiences. Photo Courtesy: Associated Press Once you’ve had a moment to reflect, share your thoughts around the table with the other guests. GUIDING QUESTIONS 1. What and whom do you see in this photograph? Whom do you recognize, if anyone? 2. If you’ve seen this photograph before, where and when have you seen it? What was your reaction to it? 3. What feelings does this photograph evoke for you? 01 JEWS and the CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT BACKGROUND ON THE PHOTO INSTRUCTIONS This photograph was taken on March 21, 1965 as the Read the following texts that challenge and complicate the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. marched with others from photograph and these narratives. Afterwards, find a chevruta (a Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in support of voting partner) and select several of the texts to think about together. -

“Stony the Road We Trod . . .” Exploring Alabama’S Civil Rights Legacy, Teacher Institute

Dear Colleague Letter: “Stony the Road We Trod . .” Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy, Teacher Institute July 11- 31, 2021 Alabama Humanities Foundation Dr. Martha Bouyer, Project Developer and Director Mrs. Laura Anderson, Project Administrator Mrs. Evelyn Davis, Administrative Assistant 205-558-3980 [email protected] DISCLAIMER: “THE STONY . .” INSTITUTE WILL BE OFFERED AS A RESIDENTIAL PROGRAM BARRING TRAVEL RESTRICTIONS RELATED TO THE SPREAD OF COVID19. “Stony the Road We Trod . .” Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy National Teacher Institute Presented By: Alabama Humanities Foundation Dr. Martha V. Bouyer, Project Director Table of Contents Dear Colleague Letter...................................................................................................................1 Overview of the Institute Activities and Assignments ..............................................................4 Host City - Birmingham ............................................................................................................... 4 The Civil Rights Years.................................................................................................................. 5 “It Began at Bethel” ...................................................................................................................... 5 Selma and Montgomery Alabama ............................................................................................... 7 Tuskegee Alabama ....................................................................................................................... -

Constance Baker Motley

THE HONORABLE CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY The Honorable Constance Baker Motley is an extraordinary person, and one of the noteworthy and surprising facts about her is how little has been written about her life and work. If, after this presentation, you are interested in learning more about her, you might read her autobiography, Equal Justice Under Law,1 and you might watch a videotape of a 1988 interview of her conducted by Alfred Aman, Professor and former dean at the Indiana University School of Law at Bloomington.2 Our library can secure the videotape for you through interlibrary loan. The bibliography lists other materials relevant to her life and work. Here are several striking facts about Constance Baker Motley, any one of which would make her worthy of serious study. She was the fifth woman, and the first Black woman, appointed to the federal bench.3 She served for almost twenty years, from 1946 to 1964, as staff attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., and was part of the "inner circle" responsible for Brown v. Board of Education, a case that many consider to be the most important of the twentieth century.4 She represented James Meredith in his successful attempt to integrate the University of Mississippi, integration that was accomplished only with the 1Constance Baker Motley, Equal Justice Under the Law (1998). 2An interview with Judge Constance Baker Motley conducted by Alfred C. Aman (1988). 3Linn Washington, Black Judges on Justice (1995), p. 760. 4Michael J. Klarman, From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality, (2004), p. -

“Stony the Road We Trod . . .” Exploring Alabama's Civil Rights

Dear Colleague Letter: “Stony the Road We Trod . .” Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy, Teacher Institute July 11- 31, 2021 Alabama Humanities Foundation Dr. Martha Bouyer, Project Developer and Director Mrs. Laura Anderson, Project Administrator Mrs. Evelyn Davis, Administrative Assistant 205-558-3980 [email protected] DISCLAIMER: “THE STONY . .” INSTITUTE WILL BE OFFERED AS A RESIDENTIAL PROGRAM BARRING TRAVEL RESTRICTIONS RELATED TO COVID19. “Stony the Road We Trod . .” Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy National Teacher Institute Presented By: Alabama Humanities Foundation Dr. Martha V. Bouyer, Project Director Table of Contents Dear Colleague Letter...................................................................................................................1 Overview of the Institute Activities and Assignments ..............................................................4 Host City - Birmingham ............................................................................................................... 4 The Civil Rights Years.................................................................................................................. 5 “It Began at Bethel” ...................................................................................................................... 5 Selma and Montgomery Alabama ............................................................................................... 7 Tuskegee Alabama .......................................................................................................................