Librarytrendsv37i2 Opt.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Franciscus Junius: Philology and the Survival of Antiquity in the Art of Northern Europe

Franciscus Junius: Philology and the survival of Antiquity in the art of northern Europe Review of: Art and Antiquity in the Netherlands and Britain. The Vernacular Arcadia of Franciscus Junius (1591 - 1677) by Thijs Weststeijn, Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2015, 452 pp., 178 colour & b/w illus. €129,00/ $164.00, ISBN13: 9789004283619, E-ISBN: 9789004283992 Ann Jensen Adams The early modern Dutch claimed as their forbearers the Batavians, a Germanic tribe described by Tacitus as located in the far reaches of the Roman Empire. Writings about art produced by the seventeenth-century descendants of these provincial peoples were proud but defensive as they continued to treat Rome as the centre of civilization. In 1632 Constantijn Huygens, secretary to northern Netherlands stadtholder Prince Frederik Henry, confided to his diary that he wished the promising artists Rembrandt van Rijn and Jan Lievens had travelled to Italy to learn from the art of antiquity and the Renaissance masters who had absorbed its lessons. But, he noted, the two young men felt that there were plenty of Italian works to be seen conveniently enough in The Netherlands. He then lavished praise on a figure of Judas by Rembrandt that he felt powerfully expressed the kind of universal truths promulgated by Latin art. Indeed, he wrote, ‘[... ] all honor to you, Rembrandt! To have brought Ilium – even all of Asia Minor – to Italy was a lesser feat than for a Dutchman [...] to have captured for The Netherlands the trophy of artistic excellence from Greece and Italy.’1 Through the first three quarters of the twentieth century this ambivalent stance toward the art of northern Europe has run like a red thread through art history as it developed as a professional discipline identified with, and defined by, the Italian Renaissance’s revival of antiquity. -

Architectural Drawings at the Avery Library

At the Confluence of Three Traditions: Architectural Drawings at the Avery Library ANGELAGIRAL NEXTTO AIRLINES, libraries today boast one of the most successfully shared databases of information. As with airline reservations, the initial impetus for the computerization of library cataloging was economic- the computer as a speedy way to communicate essentially repetitive information over vast distances. This is based on the assumption that many libraries across the land would all be cataloging the same book, and that the costly intellectual work could be shared by many libraries if there was an easy way of copying the first record entered into the database (American Library Association 1978). It was not easy to develop the international standards necessary for this cooperative effort. It took approximately 100years for the atdoption of the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules (AACR2) that are today the “Bible” of book cataloging in this country. But unlike libraries, both archives and museums collect materials that are, by definition, unique. The economic incentive of “copy cata- loging” has no validity for archives or museums and thus it has taken longer for these two kinds of institutions to agree to the concessions and compromises that are necessary to achieve standards. Two incentives seem to exist for the creation of standards for museum cataloging practices. One is the proliferation of cross-disciplinary collections and the desire for integrated catalogs (architecture as part of material culture as well as of art history and socioeconomic history). The other is the ability to incorporate the image into an automated cataloging system. Trevor Fawcett (1982), in his criticism of AACR2, called for an ef- fort to “harmonise standards” and said that “if the potential scope of Angela Giral, Avery Library, Cdumbia University, New York, NY 10027 LIBRARY TRENDS, Vol. -

LONG ISLAND HEADQUARTERS of the NEW YORK TELEPHONE COMPANY 97-105 Willoughby Street (Aka 349-371 Bridge Street, and 7 Metrotech Center), Brooklyn

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 21, 2004, Designation List 356 LP- 2144 (Former) LONG ISLAND HEADQUARTERS of the NEW YORK TELEPHONE COMPANY 97-105 Willoughby Street (aka 349-371 Bridge Street, and 7 Metrotech Center), Brooklyn. Built 1929-30; Ralph Walker of Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker, architect. Landmark Site: Borough of Brooklyn Tax Map Block 2058, Lot 1. On June 15, 2004, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the (Former) Long Island Headquarters of the New York Telephone Company building and its related Landmark Site (Item No. 1).The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. There were two speakers in favor of designation, including a representative of the owner of the building, Verizon New York Inc., and a representative of the Historic Districts Council. The Commission has also received a letter of support from Councilman David Yassky. There were no speakers opposed to designation. Summary The Long Island Headquarters of the New York Telephone Company, built in 1929-30, is a masterful example of the series of tall structures issuing from architect Ralph Walker=s long and productive association with the communications industry. Walker was a prominent New York architect whose expressive tall buildings, prolific writings and professional leadership made him one of the foremost representatives of his field during his long life. In this dramatically-massed, orange brick skyscraper, Walker illustrates his exceptional ability to apply the Art Deco style to a large office tower. Its abstract, metal ornament on the ground story display windows and the main entrance on Bridge Street, suggests constant movement, and is typical of the art of late 1920s. -

PNLA QUARTERLY the Official Journal of the Pacific Northwest Library Association

P PNLA QUARTERLY The Official Journal of the Pacific Northwest Library Association Volume 74, number 2 (Winter 2010) Volume 74, number 2 (Winter 2010) President’s Message 2 From the Editor 3 Feature Articles John Sankey. "All Guts, No Glory": A Practicum in Cataloging and Classification 4 Francesca Guerra. Simplifying Access: Metadata for Medieval Disability Studies 10 Bryan Salem. Cultivating the Enjoyment of Reading: The Prospects of Using a Leveled Library to Support English Language Learners 27 Adetoro, Niran. Globalization and the Challenges of Library and Information Services in Africa 38 Jim Tindall. Author Visits: The Elements Defined 42 Adriene Garrison. OAISTER: The Roots and the Resource 46 Call for submissions and instructions for authors Authors should include a 100-word biography and mailing address with their submissions. Submit feature articles of approximately 1,000-6,000 words on any topic in librarianship or a related field. Issue deadlines are October 1 (Fall), January 1 (Winter), April 1 (Spring), and July 1 (Summer). Please email submissions to [email protected] in rtf or doc format. PNLA Quarterly 74:2 (Winter 2010) www.pnla.org 1 President's Message Samantha Hines At our November Board Meeting, talk of the Oregon Library Association's surprising decision to leave PNLA dominated our time. We are still attempting to figure out what this means for PNLA and for our valued members in the state of Oregon. We are trying to define how this affects providing our services such as the Young Readers' Choice Award, the Leadership Institute, and our conference to our members in Oregon and to the library community in that state. -

Photo Archives and the Photographic Memory of Art History

Ca_00_Titelei_1-6_Ca_00_Titelei_1-6 12.05.11 13:00 Seite 1 Photo Archives and the Photographic Memory of Art History Edited by Costanza Caraffa Ca_00_Titelei_1-6_Ca_00_Titelei_1-6 12.05.11 13:00 Seite 2 Italienische Forschungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz Max-Planck-Institut I Mandorli Band 14 Herausgegeben von Alessandro Nova und Gerhard Wolf Ca_00_Titelei_1-6_Ca_00_Titelei_1-6 12.05.11 13:00 Seite 3 Photo Archives and the Photographic Memory of Art History Edited by Costanza Caraffa Ca_00_Titelei_1-6_Ca_00_Titelei_1-6 12.05.11 13:00 Seite 4 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Lektorat: Catherine Framm, Martin Steinbrück Herstellung: Jens Möbius, Jasmin Fröhlich Layout und Satz: Barbara Criée, Berlin Reproduktionen: LVD Gesellschaft für Datenverarbeitung mbH Druck: AZ Druck und Datentechnik, Berlin Bindung: Stein + Lehmann, Berlin © 2011 Deutscher Kunstverlag GmbH Berlin München ISBN 978-3-422-07029-5 Ca_00_Titelei_1-6_Ca_00_Titelei_1-6 12.05.11 13:00 Seite 5 5 Summary Foreword 7 Dorothea Peters From Prince Albert’s Raphael Collection Photo Archives and the Photographic to Giovanni Morelli: Photography and Memory of Art History: the Project 9 the Scientific Debates on Raphael in the Nineteenth Century 129 Costanza Caraffa From ‘photo libraries’ to ‘photo archives’. Geraldine A. Johnson On the epistemological potential -

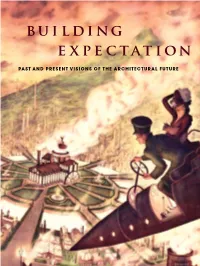

Building Expectation: Past and Present Visions of the Architectural Future

building expectation PAST AND PRESENT VISIONS OF THE ARCHITECTURAL FUTURE COVER Katherine Roy, View of Industria, 2011 This illustration, commissioned for the exhibition, depicts the great city of “Industria” as described by Comte Didier de Chousy in his 1883 novel Ignis. David Winton Bell Gallery. LEFT Margaret Bourke-White, Futurama Spectators, ca. 1939 Visitors to the General Motors pavilion in the 1939 New York World’s Fair are gently whisked past the Futurama in a track-based chair ride designed especially for couples. Courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin. Nathaniel Robert Walker Curator and Author David Winton Bell Gallery, Brown University CONTRIBUTORS to THE CATALOG Brian Horrigan UTURE F Dietrich Neumann Kenneth M. Roemer CONTRIBUTORS to THE EXHibition Archives and Special Collections Library, Vassar College Australian National Film and Sound Archive Avery Architectural and Fine Art Library, Columbia University Libraries RCHITECTURAL RCHITECTURAL A Dennis Bille Brandeis University Library HE T Brown University Libraries F Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society O Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company General Motors LLC, GM Media Archive Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Historic New Harmony, University of Southern Indiana Brian Knep expectation Maison d’Alleurs (Musée de la science-fiction, de l’utopie et des voyages extraordinaires) Mary Evans Picture Library Jane Masters Katherine Roy ND PRESENT VISIONS ND PRESENT b u i l d i n g François Schuiten A Cameron Shaw Christian Waldvogel PAST PAST Pippi Zornoza INTRODUCTION t has been said that the past is a foreign country — but it is the future that remains It is now plain and clear that neither undiscovered. -

RAYMOND HOOD and the American Skyscraper

RAYMOND HOOD and the American Skyscraper 1 RAYMOND HOOD and the American Skyscraper Curated by JO-ANN CONKLIN, JONATHAN DUVAL, and DIETRICH NEUMANN DAVID WINTON BELL GALLERY, BROWN UNIVERSITY 2 From Pawtucket to Paris: Raymond Hood’s Education and Early Work JONATHAN DUVAL On December 3, 1922, a headline on the front page of the Chicago Tribune announced the winner of the newspaper’s sensational international competition: “Howells Wins in Contest for Tribune Tower: Novelist’s Son Gains Architect Prize.” The credit due to Raymond Hood, the son of a box maker from Pawtucket, Rhode Island, was relegated to a passing mention. Attention was given instead to the slightly older and much better known John Mead Howells, son of the famous novelist and Atlantic Monthly editor William Dean Howells. Though Howells was then the more notable of the pair, Hood was quick to gain recognition in his own right and soon achieved worldwide fame. Scholars and critics agree that the Tribune Tower competition was the turning point that launched Hood’s career.1 As a consequence, though, his work before 1922 has not been adequately surveyed or scrutinized. On the surface, a description of Hood’s career before the Tribune Tower competition might seem like an inventory of mediocrity—styling radiator covers, designing a pool house shaped like a boat, writing letters to editors arguing against prohibition—ending only with the “famed turn of fortune.” 2 However, it is in these earlier years of study and work that the characteristics we associate with Raymond Hood’s architecture were formed and solidified: a blend of tradition and innovation, a focus on plan, a facility with style and ornament, an understanding of architectural illumination, and a thoughtful, iterative approach to design. -

THESIS, for Synthesis of Systematic Resources (2004-2009)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) A history of digitization: Dutch museums Navarrete Hernández, T. Publication date 2014 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Navarrete Hernández, T. (2014). A history of digitization: Dutch museums. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:28 Sep 2021 A History of Digitization: Dutch Museums A History of Digitization: Trilce Navarrete This study documented four main changes in museums’ information Dutch Museums processes brought by digitization of collections: (1) collection registration Trilce Navarrete Trilce Navarrete had a marginal and supporting role in the museum -

The Long Distance Building of the American Telephone & Telegraph

Landmarks Preservation Commission October 1, 1991; Designation List 239 LP-1748 THE LONG DISTANCE BUILDING OF THE AMERICAN TELEPHONE & TELEGRAPH COMP ANY, FIRST FLOOR INTERIOR consisting of the Sixth Avenue entrance vestibule with its auditorium alcove, the Sixth Avenue lobby with its perpendicular elevator corridors, the Church Street corridor, the Church Street entrance vestibule with its alcove, and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces, including but not limited to, floor surfaces, wall and ceiling surfaces including the mosaics, doors, elevator doors, and attached decorative elements, 32 Sixth Avenue (a/k/a 24-42 Sixth Avenue, 310-322 Church Street, 14-28 Walker Street, and 4-30 Lispenard Street), Manhattan. Built in 1911-14; Cyrus L.W. Eidlitz and McKenzie, Voorhees & Gmelin, architects. Enlarged in 1914-16; McKenzie, Voorhees & Gmelin, architects. Enlarged again and renovated in 1930-32; Ralph Walker of Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker, architect. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 192, Lot 1. On September 19, 1989, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the New York Telephone Company Building (a/k/a Long Distance Building of the American Telephone & Telegraph Company) FIRST FLOOR INTERIOR consisting of the Sixth Avenue entrance vestibule, Sixth Avenue lobby, the Church Street entrance vestibule, Church Street lobby and the lobby connecting the Sixth Avenue lobby and the Church Street lobby, and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces, including but not limited to, floor surfaces, wall and ceiling surfaces including the mosaics, doors, elevator doors, and attached decorative elements, 24-42 Sixth Avenue, Manhattan, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. -

Civic Classicism in New York City's Architecture

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2014 Apotheosis of the Public Realm: Civic Classicism in New York City's Architecture Paul Andrija Ranogajec Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/96 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] APOTHEOSIS OF THE PUBLIC REALM: CIVIC CLASSICISM IN NEW YORK CITY’S ARCHITECTURE by PAUL ANDRIJA RANOGAJEC M.A., University of Virginia, 2005 B.Arch., University of Notre Dame, 2003 A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 PAUL ANDRIJA RANOGAJEC All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Kevin D. Murphy, Chair of Examining Committee Date Claire Bishop, Executive Officer, Ph.D. Program in Art History Rosemarie Haag Bletter Sally Webster Carol Krinsky Supervision Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract Apotheosis of the Public Realm: Civic Classicism in New York City’s Architecture by Paul Andrija Ranogajec Adviser: Kevin D. Murphy In the years around the consolidation of Greater New York in 1898, a renewed interest in republican political theory among progressive liberals coincided with a new kind of civic architecture. -

The United Nations in Perspective : the Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 15-September 26, 1995

The United Nations in perspective : the Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 15-September 26, 1995 Date 1995 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/459 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art The United Nations in Perspective The Museum of Modern Art, New York June 15-September 26, 1995 A f ci^Cn^e TheMuseum of ModernArt Library In February 1947, a group of architects from Europe, Asia, nations pledging to maintain international peace and to Australia, and North and South America gathered in New solve economic, social, and humanitarian problems, it York to design the permanent headquarters of the newly was the second great effort at creating a deliberative formed United Nations Organization. In little more than world body, replacing the League of Nations, which had four months, following a period of intense creative activi been established in 1919 in the aftermath of the First ty, this group, known as the International Board of Design, World War. If the League of Nations had been a political directed by New York architect Wallace K. Harrison, pre failure, its architecture and the circumstances surround sented its proposal for a modern headquarters of startling ing its design were no less controversial. The notorious clarity and efficiency to be built in New York City (cover). competition for the League of Nations building in Their search for an appropriate architectural expression 1926-27 became a battleground between academicism for the most important symbolic building to be construct and modernism. -

Special Issue on Knowledge Organization in the Visual Arts

--N Special Issue on Knowledge Organization in the Visual Arts KNOWLEDGE ORGANIZATION VoI.20(1993)No.1 UDC 025.4+168+001.4(05) KNOWLEDGE ORGANIZATION Contents Devoted to Concept Theory, Classification, Indexing, and Knowledge Representation The joumalilithe organ of the INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR KNOWLEDGE ORGANIZATION (General Secreta Editorial riat: WoogSlt. 36a,D-6ooo Frankfurt 50) Why "Knowledge Organization"? Editors The reasons for IC's change of name .................................................. 1 Dr.Ingetraut DAHLBERG (Editor-in-Chief), Woogstr.36a, D-6OOO Frankfurt 50 Guest Editor's Editorial Dr.Robert FUGMANN, Alte Poststr.13, 0-6270 Idstein Veltman, K.: Computers and the Visual Arts ...................................... 2 ProfJean M.PERREAULT. The Library, Univ. of Alabama at Huntsville,P.D.Box 2600,Huntsville, AL 35807, USA Articles Prof.Daniel Benediktsson (Book ReviewEditor), Univenity of Iceland, Libr.& Infonn.Science Studies, Oddi 101, Reyk Bower, J. M.: Vocabulary control and the virtual database ................ 4 javik, Iceland Trant, J.: "On speaking terms": Towards virtual integration of art information ................................................................................ 8 Consulting Editors Prof.Kenneth G.B.BAKEWElL, Livetpool Business School, Brandhorst, J.P.J.: Quantifiability in iconography ............................ 12 Livetpool John Moores University, 98 Mount Pleasant, Li Grund, A.: ICONCLASS. On subject analysis of iconographic verpool L3 5UZ, U.K. representations of works of art .........................................................