Architectural Drawings at the Avery Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LONG ISLAND HEADQUARTERS of the NEW YORK TELEPHONE COMPANY 97-105 Willoughby Street (Aka 349-371 Bridge Street, and 7 Metrotech Center), Brooklyn

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 21, 2004, Designation List 356 LP- 2144 (Former) LONG ISLAND HEADQUARTERS of the NEW YORK TELEPHONE COMPANY 97-105 Willoughby Street (aka 349-371 Bridge Street, and 7 Metrotech Center), Brooklyn. Built 1929-30; Ralph Walker of Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker, architect. Landmark Site: Borough of Brooklyn Tax Map Block 2058, Lot 1. On June 15, 2004, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the (Former) Long Island Headquarters of the New York Telephone Company building and its related Landmark Site (Item No. 1).The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. There were two speakers in favor of designation, including a representative of the owner of the building, Verizon New York Inc., and a representative of the Historic Districts Council. The Commission has also received a letter of support from Councilman David Yassky. There were no speakers opposed to designation. Summary The Long Island Headquarters of the New York Telephone Company, built in 1929-30, is a masterful example of the series of tall structures issuing from architect Ralph Walker=s long and productive association with the communications industry. Walker was a prominent New York architect whose expressive tall buildings, prolific writings and professional leadership made him one of the foremost representatives of his field during his long life. In this dramatically-massed, orange brick skyscraper, Walker illustrates his exceptional ability to apply the Art Deco style to a large office tower. Its abstract, metal ornament on the ground story display windows and the main entrance on Bridge Street, suggests constant movement, and is typical of the art of late 1920s. -

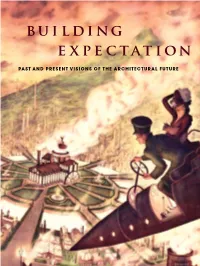

Building Expectation: Past and Present Visions of the Architectural Future

building expectation PAST AND PRESENT VISIONS OF THE ARCHITECTURAL FUTURE COVER Katherine Roy, View of Industria, 2011 This illustration, commissioned for the exhibition, depicts the great city of “Industria” as described by Comte Didier de Chousy in his 1883 novel Ignis. David Winton Bell Gallery. LEFT Margaret Bourke-White, Futurama Spectators, ca. 1939 Visitors to the General Motors pavilion in the 1939 New York World’s Fair are gently whisked past the Futurama in a track-based chair ride designed especially for couples. Courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin. Nathaniel Robert Walker Curator and Author David Winton Bell Gallery, Brown University CONTRIBUTORS to THE CATALOG Brian Horrigan UTURE F Dietrich Neumann Kenneth M. Roemer CONTRIBUTORS to THE EXHibition Archives and Special Collections Library, Vassar College Australian National Film and Sound Archive Avery Architectural and Fine Art Library, Columbia University Libraries RCHITECTURAL RCHITECTURAL A Dennis Bille Brandeis University Library HE T Brown University Libraries F Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society O Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company General Motors LLC, GM Media Archive Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Historic New Harmony, University of Southern Indiana Brian Knep expectation Maison d’Alleurs (Musée de la science-fiction, de l’utopie et des voyages extraordinaires) Mary Evans Picture Library Jane Masters Katherine Roy ND PRESENT VISIONS ND PRESENT b u i l d i n g François Schuiten A Cameron Shaw Christian Waldvogel PAST PAST Pippi Zornoza INTRODUCTION t has been said that the past is a foreign country — but it is the future that remains It is now plain and clear that neither undiscovered. -

RAYMOND HOOD and the American Skyscraper

RAYMOND HOOD and the American Skyscraper 1 RAYMOND HOOD and the American Skyscraper Curated by JO-ANN CONKLIN, JONATHAN DUVAL, and DIETRICH NEUMANN DAVID WINTON BELL GALLERY, BROWN UNIVERSITY 2 From Pawtucket to Paris: Raymond Hood’s Education and Early Work JONATHAN DUVAL On December 3, 1922, a headline on the front page of the Chicago Tribune announced the winner of the newspaper’s sensational international competition: “Howells Wins in Contest for Tribune Tower: Novelist’s Son Gains Architect Prize.” The credit due to Raymond Hood, the son of a box maker from Pawtucket, Rhode Island, was relegated to a passing mention. Attention was given instead to the slightly older and much better known John Mead Howells, son of the famous novelist and Atlantic Monthly editor William Dean Howells. Though Howells was then the more notable of the pair, Hood was quick to gain recognition in his own right and soon achieved worldwide fame. Scholars and critics agree that the Tribune Tower competition was the turning point that launched Hood’s career.1 As a consequence, though, his work before 1922 has not been adequately surveyed or scrutinized. On the surface, a description of Hood’s career before the Tribune Tower competition might seem like an inventory of mediocrity—styling radiator covers, designing a pool house shaped like a boat, writing letters to editors arguing against prohibition—ending only with the “famed turn of fortune.” 2 However, it is in these earlier years of study and work that the characteristics we associate with Raymond Hood’s architecture were formed and solidified: a blend of tradition and innovation, a focus on plan, a facility with style and ornament, an understanding of architectural illumination, and a thoughtful, iterative approach to design. -

The Long Distance Building of the American Telephone & Telegraph

Landmarks Preservation Commission October 1, 1991; Designation List 239 LP-1748 THE LONG DISTANCE BUILDING OF THE AMERICAN TELEPHONE & TELEGRAPH COMP ANY, FIRST FLOOR INTERIOR consisting of the Sixth Avenue entrance vestibule with its auditorium alcove, the Sixth Avenue lobby with its perpendicular elevator corridors, the Church Street corridor, the Church Street entrance vestibule with its alcove, and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces, including but not limited to, floor surfaces, wall and ceiling surfaces including the mosaics, doors, elevator doors, and attached decorative elements, 32 Sixth Avenue (a/k/a 24-42 Sixth Avenue, 310-322 Church Street, 14-28 Walker Street, and 4-30 Lispenard Street), Manhattan. Built in 1911-14; Cyrus L.W. Eidlitz and McKenzie, Voorhees & Gmelin, architects. Enlarged in 1914-16; McKenzie, Voorhees & Gmelin, architects. Enlarged again and renovated in 1930-32; Ralph Walker of Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker, architect. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 192, Lot 1. On September 19, 1989, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the New York Telephone Company Building (a/k/a Long Distance Building of the American Telephone & Telegraph Company) FIRST FLOOR INTERIOR consisting of the Sixth Avenue entrance vestibule, Sixth Avenue lobby, the Church Street entrance vestibule, Church Street lobby and the lobby connecting the Sixth Avenue lobby and the Church Street lobby, and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces, including but not limited to, floor surfaces, wall and ceiling surfaces including the mosaics, doors, elevator doors, and attached decorative elements, 24-42 Sixth Avenue, Manhattan, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. -

Civic Classicism in New York City's Architecture

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2014 Apotheosis of the Public Realm: Civic Classicism in New York City's Architecture Paul Andrija Ranogajec Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/96 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] APOTHEOSIS OF THE PUBLIC REALM: CIVIC CLASSICISM IN NEW YORK CITY’S ARCHITECTURE by PAUL ANDRIJA RANOGAJEC M.A., University of Virginia, 2005 B.Arch., University of Notre Dame, 2003 A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 PAUL ANDRIJA RANOGAJEC All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Kevin D. Murphy, Chair of Examining Committee Date Claire Bishop, Executive Officer, Ph.D. Program in Art History Rosemarie Haag Bletter Sally Webster Carol Krinsky Supervision Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract Apotheosis of the Public Realm: Civic Classicism in New York City’s Architecture by Paul Andrija Ranogajec Adviser: Kevin D. Murphy In the years around the consolidation of Greater New York in 1898, a renewed interest in republican political theory among progressive liberals coincided with a new kind of civic architecture. -

The United Nations in Perspective : the Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 15-September 26, 1995

The United Nations in perspective : the Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 15-September 26, 1995 Date 1995 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/459 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art The United Nations in Perspective The Museum of Modern Art, New York June 15-September 26, 1995 A f ci^Cn^e TheMuseum of ModernArt Library In February 1947, a group of architects from Europe, Asia, nations pledging to maintain international peace and to Australia, and North and South America gathered in New solve economic, social, and humanitarian problems, it York to design the permanent headquarters of the newly was the second great effort at creating a deliberative formed United Nations Organization. In little more than world body, replacing the League of Nations, which had four months, following a period of intense creative activi been established in 1919 in the aftermath of the First ty, this group, known as the International Board of Design, World War. If the League of Nations had been a political directed by New York architect Wallace K. Harrison, pre failure, its architecture and the circumstances surround sented its proposal for a modern headquarters of startling ing its design were no less controversial. The notorious clarity and efficiency to be built in New York City (cover). competition for the League of Nations building in Their search for an appropriate architectural expression 1926-27 became a battleground between academicism for the most important symbolic building to be construct and modernism. -

Ordertastegrace00haysrich.Pdf

s University of California Berkeley University of California Bancroft Library /Berkeley Regional Oral History Office William Charles Hays ORDER, TASTE, AND GRACE IN ARCHITECTURE An Interview Conducted by Edna Tartaul Daniel Berkeley 1968 William C. Hays on his 77th birthday In the garden of his home At 2924 Derby Street, Berkeley. All uses of this manuscript are covered by an agreement between the Regents of the University of California and William Charles Hays, dated 25 April 1961. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. FOREWORD William C. Hays was interviewed at length in 1959 as a part of a program of the Regional Oral History Office to record the history of the University of California. This final manu script was not completed until 1968, five years following Mr. Hays death. The time and the method of completing this manuscript has been unusual, in part a reflection of Mr. Hays wish to complete a correct and valuable history and his inability because of poor health to even begin to do all the hundreds of hours of rewriting that became his objective. Final work on the manuscript, after Mr. Hays death ended the possibility of his making the rough transcript into a polished manuscript, was delayed until funds could be obtained. -

Hugh Ferriss's the Metropolis of Tomorrow

THE METROPOLIS OF TOMORROW THE METROPOLIS OF TOMORROW BY Hugh Ferriss IVES WASHBURN, PUBLISHER NEW YORK MCMXXIX COPYRIGHT. 1929, BY HUGH FERRISS PMnted In The United States of America — To those men who, as Commissioners of numerous American municipalities, are laboring upon the economic, legal, social and engineering aspects of City Planning, this book which aspires to add a visual element to the endeavor—is respectfully inscribed Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from IVIetropolitan New York Library Council - METRO http://archive.org/details/mettomoOOferr FOREWORD REALIZINC, as the author does, how dubious a business is that of "Prophecy", he at once disclaims any assumption of the prophet's robe. How are the cities of the future really going to look? Heaven only knows! Certainly the author has had no thought, while sketching these visualizations, that he had been vouchsafed any Vision. He will only claim that these studies are not entirely random shots in the dark, and that his foreshadowings and interpretations spring from something at least more trustworthy than personal phantasy. The fact is, these drawings have for the greater part been made in leisure moments during the fifteen years or so in which it has been the author's daily task to work, as Illustrator or Consulting Designer, on the typical buildings which our contemporary architectural firms are erecting, day by day, in the larger cities. He should not be charged with waywardness if he has sought, during this period, to discover some of the trends which underlie the vast miscellany of contemporary building, or wondered (in drawings) where these trends may possibly, or even probably, lead. -

INSTIT"'ON Association of Research Libraries, Washington, DC Office Of

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 257 459 IR 051 126 AUTHOR Merrill-Oldham, Jan TITLE Preservation Education in ARL Libraries. SPEC Kit 113. INSTIT" 'ON Association of Research Libraries, Washington, D.C. Office of Management Studies. PUB DATE Apr 85 NOTE 173p. AVAILABLE FROMSystems and Procedures Exchange Center, Office of Management Studies, Association of Research Libraries, 1527 New Hampshire Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20036 ($20.00 per kit 'nevoid). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) -- Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE M701 Plum Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Libraries; Commamications; Emergency Programs; Guidelines; Higher Education; Job Training; Library Administration; *Library Collections; Library Materials; *Library Personnel; Methods; Policy; *Preservation; *Program Development; Research Libraries; *Training Methods IDENTIFIERS Association of Research Libraries ABSTRACT This kit is the result of a written request for sample materials from 35 ARL (Association of ResearchLibraries) members known to have active preservation programs. Twenty-three libraries responded, and of those, 16 contributed documents--someof which are included here. This kit contains: four preservation-related policy statements; 32 examples of staff training materials, for preservation orientation, general information, audiovisual programs, specific information, treatment procedures, library newsletters, and hands-on workshops; 14 examples of reader education, including handouts, newspapers and other publication articles, and signs; -

Librarytrendsv37i2 Opt.Pdf

ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. LIBRARY TRENDS FALL 1988 37(2)117-264 Linking Art Objects and Art Information Deirdre C. Stam and Angela Giral Issue Editors University of Illinois Graduate School of Library and Information Science This Page Intentionally Left Blank Linking Art Objects and Art Information Deirdre C. Stam and Angela Giral Issue Editors CONTENTS Introduction Deirdre C. Stam and Angela Giral 117 How an Art Historian Connects Art Objects and Information Richard Brilliant 120 Museum Data Bank Research Report: The Yogi and the Registrar David W. Scott 130 Documenting Our Heritage Evelyn K. Samuel 142 Access to Iconographical Research Collections Karen Markey 154 The Museum Prototype Project of the J. Paul Getty Art History and Information Program: A View from the Library Nancy S. Allen 175 An Art Information System: From Integration to Interpretation Patricia J. Barnett 194 Consideration in the Design of Art Scholarly Databases David Bearman 206 Thinking About Museum Information Patricia Ann Reed and Jane Sledge 220 CONTENTS(Cont.) At the Confluence of Three Traditions: Architectural Drawings at The Avery Library of Columbia Angela Giral 232 Achieving the Link Between Art Object and Documentation: Experience in the British Architectural Library Jan Floris van der Wateren 243 One-Stop Shopping: RLIN as a Union Catalog for Research Collections at the Getty Center James M. Bower 252 About the Contributors 263 Introduction DEIRDREC. STAMAND ANGELAGIRAL REPRFSENTINGA DEPARTURE from the usual pattern of Library Trends, this issue joins the concerns of traditional art librarianship both to topics found in information science-such as the nature and use of in- formation-and to topics found in recent art historical writing, specifi- cally the examination of the fundamental functions of the discipline and the construction of its information base. -

Facade of Many Faces: a Hybrid Skyscraper

Façade of Many Faces: A Hybrid Skyscraper A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture In the School of Architecture and Interior Design of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning March 16th by: Rachael Green B.S. Architecture, University of Cincinnati, 2018 Minor in Sociology, University of Cincinnati, 2018 Committee Chairs: Edward Mitchell Vincent Sansalone ii Abstract: Skyscrapers of the late 19th century looked vastly different than they do today. Historically, the skyscraper began as a single form extrusion containing a single program. Throughout history the skyscraper took on many new forms. Zoning and setback laws of the 1960’s changed the way that the skyscraper looked and was thought about. There has always been a race and desire to have the tallest skyscraper in New York City, and as technology developed it allowed for skyscrapers to be built taller. New York City would become one of the most prominent cities for the skyscraper as well as one of the most iconic skylines. As new heights were reached there was a split from the once ornamental and sculptural skyscraper. Both in past and present day New York City there is an emphasis on designing the tallest and most slender skyscraper. As previously mentioned with the emphasis on height, there was importance placed on the glass tower. Over time this led to the skyscraper becoming an ambiguous and aesthetically standardized building. Office towers and apartment buildings look the same and offer no indication as to what the skyscraper contains. -

Skybridges: a History and a View to the Near Future Author

CTBUH Research Paper ctbuh.org/papers Title: Skybridges: A History and a View to the Near Future Author: Antony Wood, Chief Executive Officer, Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat Subject: Vertical Transportation Keywords: Development Skybridges Urban Habitat Vertical Transportation Publication Date: 2019 Original Publication: International Journal of High-Rise Buildings Volume 8 Number 1 Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Antony Wood International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of March 2019, Vol 8, No 1, 1-18 High-Rise Buildings https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2019.8.1.1 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php Skybridges: A History and a View to the Near Future Antony Wood and Daniel Safarik† Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, 104 South Michigan Avenue, Suite 620, Chicago, Illinois, 60603, USA Abstract As many architects and visionaries have shown over a period spanning more than a century, the re-creation of the urban realm in the sky through connections between buildings at height has a vast potential for the enrichment of our cities. To many it seems nonsensical that, although the 20th and now 21st century, have clearly seen a push towards greater height and urban density in our major urban centers, the ground-pavement level remains almost exclusively the sole physical plane of connection. As the world rapidly urbanizes, greater thought needs to be expended on how horizontal space can be developed at height. This paper briefly describes the history, present classifications and uses, and potential future development potential of skybridges between tall buildings.