Civic Classicism in New York City's Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Where Architecture Expert Paul Goldberg Comments on the History of New York's Famous Skyscrapers. As You Do So, Complete

Can you identify any of these buildings? What do they all have in common? Which one do you like best? Read where architecture expert Paul Goldberg comments on the history of New York’s famous skyscrapers. As you do so, complete the following tasks: · In New York buildings are not only buildings, they become ___________________ · New York took over Chicago as regards skyscrapers in ___________________. · The Woolworth building was the tallest building worldwide for _________________. · The _______________ defined the Manhattan skyline. · They are trying to keep a memory of the people who were lost and also to show New York’s ______________________________. · New York stands out from the other cities as the embodiment of ____________________. Woolworth Building; Empire State Building; Chrysler Building; Flatiron; Hearst Tower The Woolworth Building, at 57 stories (floors), is one of the oldest—and one of the most famous—skyscrapers in New York City. It was the world’s tallest building for 17 years. More than 95 years after its construction, it is still one of the fifty tallest buildings in the United States as well as one of the twenty tallest buildings in New York City. The building is a National Historic Landmark, having been listed in 1966. The Empire State Building is a 102-story landmark Art Deco skyscraper in New York City at the intersection of Fifth Avenue and West 34th Street. Like many New York building, it has become seen as a work of art. Its name is derived from the nickname for New York, The Empire State. It stood as the world's tallest building for more than 40 years, from its completion in 1931 until construction of the World Trade Center's North Tower was completed in 1972. -

Proceedings Op the Twenty-Third Annual Meeting Op the Geological Society Op America, Held at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, December 21, 28, and 29, 1910

BULLETIN OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA VOL. 22, PP. 1-84, PLS. 1-6 M/SRCH 31, 1911 PROCEEDINGS OP THE TWENTY-THIRD ANNUAL MEETING OP THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OP AMERICA, HELD AT PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA, DECEMBER 21, 28, AND 29, 1910. Edmund Otis Hovey, Secretary CONTENTS Page Session of Tuesday, December 27............................................................................. 2 Election of Auditing Committee....................................................................... 2 Election of officers................................................................................................ 2 Election of Fellows................................................................................................ 3 Election of Correspondents................................................................................. 3 Memoir of J. C. Ii. Laflamme (with bibliography) ; by John M. Clarke. 4 Memoir of William Harmon Niles; by George H. Barton....................... 8 Memoir of David Pearce Penhallow (with bibliography) ; by Alfred E. Barlow..................................................................................................................... 15 Memoir of William George Tight (with bibliography) ; by J. A. Bownocker.............................................................................................................. 19 Memoir of Robert Parr Whitfield (with bibliography by L. Hussa- kof) ; by John M. Clarke............................................................................... 22 Memoir of Thomas -

Fish Commission Biennial Report

California. of Fish ana Gair.e " Dept. §iennial Report 1903-1904. ^jifTi'nxP ''C^<\•i-^r^^.i^Y^ Wmm "'»«'' Hi Ul. i. iGOMMISSIONE California. Dept. of Fish and Game, Biennial Report 1903-1904. (bound volume) DATE DUE _^ California- Dept. of Fish and Game. Biennial Report 1903-1904. ^ (bound volume) — APR X5'93 y^l ^o '93 California Resources Agency Library 1416 9th Street, Room 117 Sacramento, California 95814 .P.A!; *f^y liiUk^u. / EIGHTEENTH BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE State Board of Fish Commissioners STATE OF CALIFORNIA, FOR THE YE^LRS 1903-1904. COMMISSIONERS: W. W. VAN ARSDALE, President, San Francisco. W. E. GERBER, - - - - Sacramento. CHAS. A. VOGELSANG, Chief Deputy, Mills Building, San Francisco, Cal. SACRAMENTO: : : state W. W. SHANNON, : superintendent printing. 1904. EIGHTEENTH BIENNIAL REPORT OF THE STATE BOARD OF FISH COMMISSIONERS. To Hon. George C. Pardee, Governor of the State of California : Sir: In accordance with law, the vState Board of Fish Commissioners has the honor to siihmit for your consideration its Eighteenth Biennial Report, being a record of its work and expenditures from September 1, 1902, to September 1, 1904. We submit, also, the recommendations which our experience in carry- ing on this important work has suggested, as tending, in our jvidgment, to the betterment of both the fish and the game interests. Since the Seventeenth Biennial Report was suVmiitted, the personnel of this Board has undergone one change. H. W. Keller tendered his resignation on April 24, 1903. On May 6, 1903, W. W. Van Arsdale Avas elected President of the Board, vice H. W. -

New Hope in Altman's Aftermath

Belkin Burden Wenig & Goldman, LLP EDITORS Magda L. Cruz UPDATE Aaron Shmulewitz Kara I. Rakowski DECEMBER 2015 | VOLUME 33 LITIGATION UPDATE INSIDE THIS ISSUE LITIGATION UPDATE NEW HOPE IN ALTMAN’S AFTERMATH NEW HOPE IN ALTMAN’S AFTERMATH .......................1 ADMINISTRATIVE LAW UPDATE DEREGULATE RENT REGULATED APARTMENTS THROUGH HIGH INCOME HIGH RENT DEREGULATION IN 2016...............................5 CO-OP | CONDO CORNER BY AARON SHMULEWITZ ...6 ADMINISTRATIVE By Matthew S. Brett stem the Altman tide. Specifically, the Appellate LAW UPDATE Term, First Department (a court below the NEW YORK CITY On the morning of Tuesday, Appellate Division) issued a decision on November PROMULGATES NEW April 28, 2015, the Appellate 12, 2015 in the case of Aimco 322 East 61st Street, LAWS AFFECTING TENANT Division, First Department LLC v. Brosius in which the court refused to apply the holding of Altman. The case was notable in BUYOUT PRACTICES ..........8 quietly released over 40 decisions. At the top of the that the Appellate Term was explicitly rejecting TRANSACTIONS alphabetical list released by the Appellate the application of a higher court precedent. This OF NOTE.............................8 Division was Altman v 285 W. Fourth, LLC—a is a rare, but not unprecedented event whereby a case that seemed to crater the landscape of high court indicates that a case decided by the higher NOTABLE rent luxury deregulation as it existed prior to the court is simply wrong. ACHIEVEMENTS .................9 Rent Act of 2015. Distilled down to its simplest form, Altman was a decision that eliminated post- Aimco came on the heels of a decision from the vacancy deregulation (deregulating an apartment DHCR in July 2015 (Matter of Terrance Trainer) after it became vacant by lawfully raising the post- that rejected Altman —at least by implication. -

118 West 22Nd Street 118 West 22Nd Street ™ 118 West 22Nd Street

™ 118 WEST 22ND STREET 118 WEST 22ND STREET ™ 118 WEST 22ND STREET 118 WEST 22ND STREET Built in 1911 by the architect Frederick C. Zobel, the 100,000 square foot 12-story loft building at 118 West 22nd Street is a perfect choice for companies looking for office space in the iconic Flatiron District, located just one block from Madison Square Park. Commuters have easy access to PATH and 1, C, F, E, N, M and R subway lines at nearby 23rd Street Station. Fantastic amenities can be found along Avenue of the Americas and 23rd Street; from Trader Joe’s and Eataly to Shake Shack and Blue Mercury Coffee, the area offers an abundance of food, beverage and retail options for all. The building welcomes tenants and visitors with an elegant light brown limestone facade that still boasts many of its original metal cladding and stucco decorations. ™ 118 WEST 22ND STREET THE BUILDING Location West 22nd Street between Avenue of the Americas and 7th Avenue Year Built 1911 Renovations Lobby - 2010; Facade Restoration - 2016 Building Size 100,000 SF Floors 12, plus mezzanine, 2 below-grade ™ 118118 WEST WEST 22ND22ND STREET TYPICAL FLOORFLOOR PLANPLAN 8,500 RSFRSF WEST 22ND STREET ™ 118 WEST 22ND STREET BUILDING SPECIFICATIONS Location West 22nd Street between Avenue Windows Double-insulated, operable of the Americas and 7th Avenue Fire & Class E fire alarm system with command Year Built 1911 Life Safety Systems station, building fully sprinklered Architect Frederick C. Zobel Security Access Attended lobby 9 am - 6 pm M-F, video intercom, closed-circuit cameras Building Size 100,000 SF Building Hours 24/7 tenant access; Attended lobby 12, plus mezzanine, 2 below-grade Floors 9 am - 6 pm M-F Construction Masonry & limestone Telecom Providers Verizon, Spectrum, Pilot Renovations Lobby - 2010; facade restoration - 2016 Cleaning Common areas M-F Loss Factor Full floors: 27%; multi-tenanted floors: Bicycle Storage None no greater than 35% Municipal Incentives N/A Floor Loads (per SF) 120 lbs./SF Transportation Subway: Lines 1 and 2 via 23rd Street 11'5" Avg Slab-to-Slab Station. -

Old Buildings, New Views Recent Renovations Around Town Have Uncovered Views of Manhattan That Had Been Hiding in Plain Sight

The New York Times: Real Estate May 7, 2021 Old Buildings, New Views Recent renovations around town have uncovered views of Manhattan that had been hiding in plain sight. By Caroline Biggs Impressions: 43,264,806 While New York City’s skyline is ever changing, some recent construction and additions to historic buildings across the city have revealed some formerly hidden, but spectacular, views to the world. These views range from close-up looks at architectural details that previously might have been visible only to a select few, to bird’s-eye views of towers and cupolas that until The New York Times: Real Estate May 7, 2021 recently could only be viewed from the street. They provide a novel way to see parts of Manhattan and shine a spotlight on design elements that have largely been hiding in plain sight. The structures include office buildings that have created new residential spaces, like the Woolworth Building in Lower Manhattan; historic buildings that have had towers added or converted to create luxury housing, like Steinway Hall on West 57th Street and the Waldorf Astoria New York; and brand-new condo towers that allow interesting new vantages of nearby landmarks. “Through the first decades of the 20th century, architects generally had the belief that the entire building should be designed, from sidewalk to summit,” said Carol Willis, an architectural historian and founder and director of the Skyscraper Museum. “Elaborate ornament was an integral part of both architectural design and the practice of building industry.” In the examples that we share with you below, some of this lofty ornamentation is now available for view thanks to new residential developments that have recently come to market. -

Assessment Actions

Assessment Actions Borough Code Block Number Lot Number Tax Year Remission Code 1 1883 57 2018 1 385 56 2018 2 2690 1001 2017 3 1156 62 2018 4 72614 11 2018 2 5560 1 2018 4 1342 9 2017 1 1390 56 2018 2 5643 188 2018 1 386 36 2018 1 787 65 2018 4 9578 3 2018 4 3829 44 2018 3 3495 40 2018 1 2122 100 2018 3 1383 64 2017 2 2938 14 2018 Page 1 of 604 09/27/2021 Assessment Actions Owner Name Property Address Granted Reduction Amount Tax Class Code THE TRUSTEES OF 540 WEST 112 STREET 105850 2 COLUM 226-8 EAST 2ND STREET 228 EAST 2 STREET 240500 2 PROSPECT TRIANGLE 890 PROSPECT AVENUE 76750 4 COM CRESPA, LLC 597 PROSPECT PLACE 23500 2 CELLCO PARTNERSHIP 6935500 4 d/ CIMINELLO PROPERTY 775 BRUSH AVENUE 329300 4 AS 4305 65 REALTY LLC 43-05 65 STREET 118900 2 PHOENIX MADISON 962 MADISON AVENUE 584850 4 AVENU CELILY C. SWETT 277 FORDHAM PLACE 3132 1 300 EAST 4TH STREET H 300 EAST 4 STREET 316200 2 242 WEST 38TH STREET 242 WEST 38 STREET 483950 4 124-469 LIBERTY LLC 124-04 LIBERTY AVENUE 70850 4 JOHN GAUDINO 79-27 MYRTLE AVENUE 35100 4 PITKIN BLUE LLC 1575 PITKIN AVENUE 49200 4 GVS PROPERTIES LLC 559 WEST 164 STREET 233748 2 EP78 LLC 1231 LINCOLN PLACE 24500 2 CROTONA PARK 1432 CROTONA PARK EAS 68500 2 Page 2 of 604 09/27/2021 Assessment Actions 1 1231 59 2018 3 7435 38 2018 3 1034 39 2018 3 7947 17 2018 4 370 1 2018 4 397 7 2017 1 389 22 2018 4 3239 1001 2018 3 140 1103 2018 3 1412 50 2017 1 1543 1001 2018 4 659 79 2018 1 822 1301 2018 1 2091 22 2018 3 7949 223 2018 1 471 25 2018 3 1429 17 2018 Page 3 of 604 09/27/2021 Assessment Actions DEVELOPM 268 WEST 84TH STREET 268 WEST 84 STREET 85350 2 BANK OF AMERICA 1415 AVENUE Z 291950 4 4710 REALTY CORP. -

Feature Property

Woolworth Building An early skyscraper, National Historic Landmark since 1966, and New York City landmark since 1983, the Woolworth Building was the tallest building in the world upon completion in 1913 until 1930. 233 Broadway New York, NY Neo-Gothic Style Façade Architectural Details Straight lines of the “piers” ascend upwards to the over-scaled pyramidal cap Top Portion of Building 57th Floor Observation Deck until 1940 Building Use Transition U-Shaped Portion- 29 Stories Tall Top 30 Floors Conversion to Luxury Residential Condominiums Lobby Details Marble Finishes Vaulted Ceiling Mosaics Stained-Glass Ceiling Light Bronze Fittings PROJECT SUMMARY Project Description A classic early high-rise architectural landmark incorporating Gothic themes with the modern idea of a skyscraper. The 1913 Gothic Revival building featured gargoyles, arches and flying buttresses. Bordered by Broadway, Barclay Street, Church Street, and Park Place, the building is located in New York City’s Financial District. Building Description 57 floor, Neo-Gothic designed, steel-rigid frame structure with light gray, limestone-colored, glazed, terra-cotta façade Official Building Name Woolworth Building Location 233 Broadway, New York City, NY Construction Start - 1910 | Completion- 1913 History Tallest building in the World 1913 - 1930 Named the “Cathedral of Commerce” upon completion Construction Cost $13.5 million LEADERSHIP | PROJECT TEAM | DESIGN | CONSTRUCTION U.S. President Woodrow Wilson New York City Mayor William Jay Gaynor Building Owner 1913 F.W. Woolworth Company Developer F.W. Woolworth Company & Irving National Exchange Bank Architect Cass Gilbert Structural Engineering Gunvald Aus Company Primary Contractor Thompson-Starrett & Company Current Use Office | Residential (top 30 floors) BUILDING CONSTRUCTION & AMENITIES SUMMARY Size 1.3 Million GSF Height 792 Feet | 241 Meters Number of Floors 57 (above ground) Design 57 floor, Neo-Gothic architectural style, featuring gargoyles, arches and flying buttresses. -

Iron & Steel Entrepreneurs on the Delaware GSL22 12.15

Today we get excited about iPhones, iPads, and the like, but 160 years ago, when the key innovations were happening in railroads, iron, and steel, many people actually got excited about . I-beams! And among the centers of such excitement was Trenton, New Jersey. Figure 1: Petty's Run Steel renton became a center of these iron and steel innovations in the 19th Site, Trenton, 2013. In the century for the same reasons that spur innovation today—location, 1990s Hunter Research, Inc. uncovered the foundation of Tinfrastructure, skilled workers, and entrepreneurs. The city’s Benjamin Yard's 1740s steel resources attracted three of the more brilliant and visionary furnace, one of the earliest entrepreneurs of the 1840s—Peter Cooper, Abram S. Hewitt, and John A. steel making sites in the Roebling. They established iron and steel enterprises in Trenton that colonies. The site lies lasted for more than 140 years and helped shape modern life with between the N.J. State innovations in transportation, construction, and communications. Their House and the Old Barracks, legacy in New Jersey continues today with landmark suspension background, and the State and Mercer County have bridges, one of the State’s finest historic parks, repurposed industrial preserved and interpreted it. buildings, one of the best company towns in America, and in a new C.W. Zink museum. Abram Hewitt, Peter Cooper’s partner and future son-in-law, highlighted Trenton’s assets in 1853: “The great advantage of Trenton is that it lies on the great route between New York and Philadelphia” which were the two largest markets in the country. -

Course Syllabus Jump to Today Modern American Architecture Columbia University, GSAPP Spring 2020, Mondays 11-1 Professor Jorge Otero- Pailos Ph.D

Course Syllabus Jump to Today Modern American Architecture Columbia University, GSAPP Spring 2020, Mondays 11-1 Professor Jorge Otero- Pailos Ph.D. TA: Shuyi [email protected] M.S TA: Mariana Ávila [email protected] Course Description: This course is a survey of American Modern Architecture since the country’s first centennial. As America ascended to its current position of hegemony during the late 19th and 20th centuries, its architects helped refashion the built environment to serve the needs of a growing and ever-diverse population. Hand in hand with the satisfaction of pragmatic requirements, American architects were called upon to fulfill deeper psychological wants, such as the country’s desire to have a national History. The American complex about the brevity, artificiality, and exterior dependency of its history, structured, with varying degrees of intensity, the evolution of the architectural discipline. Out of this deep-seated, and by no means exhausted, anxiety about producing, preserving, and identifying American history, came a sophisticated architectural culture; one capable of foiling, exploiting, subverting, and manipulating the various contradictions of modernity. From the standpoint of this relationship between history and modernity, we will analyze the American architectural struggle to be progressive and accepted, exceptional and customary, and to simultaneously capture the future and the past. Each lecture will analyze the production and reception of built (and written) works by renowned figures and anonymous builders. The question of History will help us discern the terms of engagement between architecture and other disciplines over time, such as: preservation, planning, real estate development, politics, health, ecology, sociology, and philosophy. -

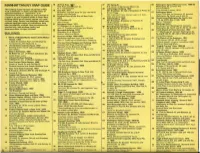

Manhattan N.V. Map Guide 18

18 38 Park Row. 113 37 101 Spring St. 56 Washington Square Memorial Arch. 1889·92 MANHATTAN N.V. MAP GUIDE Park Row and B kman St. N. E. corner of Spring and Mercer Sts. Washington Sq. at Fifth A ve. N. Y. Starkweather Stanford White The buildings listed represent ali periods of Nim 38 Little Singer Building. 1907 19 City Hall. 1811 561 Broadway. W side of Broadway at Prince St. First erected in wood, 1876. York architecture. In many casesthe notion of Broadway and Park Row (in City Hall Perk} 57 Washington Mews significant building or "monument" is an Ernest Flagg Mangin and McComb From Fifth Ave. to University PIobetween unfortunate format to adhere to, and a portion of Not a cast iron front. Cur.tain wall is of steel, 20 Criminal Court of the City of New York. Washington Sq. North and E. 8th St. a street or an area of severatblocks is listed. Many glass,and terra cotta. 1872 39 Cable Building. 1894 58 Housesalong Washington Sq. North, Nos. 'buildings which are of historic interest on/y have '52 Chambers St. 1-13. ea. )831. Nos. 21-26.1830 not been listed. Certain new buildings, which have 621 Broadway. Broadway at Houston Sto John Kellum (N.W. corner], Martin Thompson replaced significant works of architecture, have 59 Macdougal Alley been purposefully omitted. Also commissions for 21 Surrogates Court. 1911 McKim, Mead and White 31 Chembers St. at Centre St. Cu/-de-sac from Macdouga/ St. between interiorsonly, such as shops, banks, and 40 Bayard-Condict Building. -

Samuel T. Hauser and Hydroelectric Development on the Missouri River, 1898--1912

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1979 Victim of monopoly| Samuel T. Hauser and hydroelectric development on the Missouri River, 1898--1912 Alan S. Newell The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Newell, Alan S., "Victim of monopoly| Samuel T. Hauser and hydroelectric development on the Missouri River, 1898--1912" (1979). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4013. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4013 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUB SISTS. ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD LIBRARY 7' UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE: 1979 A VICTIM OF MONOPOLY: SAMUEL T. HAUSER AND HYDROELECTRIC DEVELOPMENT ON THE MISSOURI RIVER, 1898-1912 By Alan S. Newell B.A., University of Montana, 1970 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1979 Approved by: VuOiAxi Chairman,lairman, Board of Examiners De^n, Graduate SctooI /A- 7*? Date UMI Number: EP36398 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.