Ordertastegrace00haysrich.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Preservation Committee Meeting Agenda Tuesday April 13, 2021 5:30 P.M

HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMITTEE MEETING AGENDA TUESDAY APRIL 13, 2021 5:30 P.M. REMOTE MEETING COVID-19 ADVISORY NOTICE On March 16, 2020, the Marin County Public Health Officer issued a legal shelter in place order. On March 31, 2020 the Marin County Public Health Officer issued an updated legal order directing all residents to shelter at their place of residence through May 3, 2020, except to perform Essential Activities. The March 31, 2020 Order prohibits the gathering of any number of people occurring outside a household unit, except for the limited purpose of participating in an Essential Activity. Additional information is available at https://coronavirus.marinhhs.org/. This meeting is necessary so that the City of Belvedere can continue its business and is considered an Essential Activity. Consistent with Executive Orders No. 25-20 and No. 29-20 from the Executive Department of the State of California, the meeting will not be physically open to the public. Members of the Planning Commission and staff will participate in this meeting remotely as permitted under said Executive Orders. As always, the public may submit comments in advance of the meeting by emailing the Senior Planner at: [email protected]. Please write “Public Comment” in the subject line. Comments submitted one hour prior to the commencement of the meeting will be presented to the Committee and included in the public record for the meeting. Those received after this time will be added to the record and shared with Committee after the meeting. The meeting will be available to the public through Zoom video conference. -

In Memory of Walter Cope, Architect of Bryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Bryn Mawr College Publications, Special Books, pamphlets, catalogues, and scrapbooks Collections, Digitized Books 1908 In Memory of Walter Cope, Architect of Bryn Mawr College M. Carey Thomas Bryn Mawr College Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_books Part of the Liberal Studies Commons, and the Women's History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Custom Citation Thomas, M. Carey, In Memory of Walter Cope, Architect of Bryn Mawr College. (Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania: Bryn Mawr College, 1908). This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_books/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. #JI IN MEMORY OF WALTER COPE ARCHITECT OF BRYN MAWR COLLEGE Address delivered by President M. Carey Thomas at a Memorial Service held at Bryn Mawr College, November 4, 1902. Published in the Bryn Mawr College Lantern, February, 1905. Reprinted by request, June, 1908. , • y • ./S-- I I .... ~ .. ,.,, \ \ " "./. "",,,, ~ / oj. \ .' ' \£,;i i f 1 l; 'i IN MEMORY OF \ WALTER COPE ARCHITECT OF BRYN MAWR COLLEGE Address delivered by President M. Carey Thomas at a Memorial Servic~ held at Bryn Mawr College, November 4, 1902. Published in the Bryn Mawr College Lantern, February, 1905. Reprinted by request, June, 1908. • T his memorial address was published originally in the Bryn Mawr College Lantern, Februar)I, I905, and is now reprinted by perntission of the Board of Editors of the Lantern, with slight verbal changesJ in response to the request of some of the many adm1~rers of the architectural beauty of Bryn 1\;[awr College, w'ho believe that it should be more widely l?nown than it is that the so-called American Collegiate Gothic was created for Bryn Mawr College by the genius of John Ste~vardson and ""Valter Cope. -

Published Occasionally by the Friends of the Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley, California 94720

PUBLISHED OCCASIONALLY BY THE FRIENDS OF THE BANCROFT LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94720 No. J4 February 1^80 In the beginning - wet who have beginnings, Bust think in ten end, Juet for thought's sake* - in the beginning was^plaeny failve, as it always does, and we have at once dead Matter, and Energy, or on aide by aids,—in aotive eunJunuLlmi fuieyei-r /"what we* -tic universe of Force and Matter is the dead itflalduyof previous 4 •Bftofa are In the. beginning 1 Matter and Fo4 CAUWPITCA m+Hti \ aautt, thayflntoraot forever^ and are inter-dependent, -fiti xm - ^A^dju^^LJ^ waturlallstie unlv»reO| always, ^. m Lawrence's Manuscript of Fantasia of the Unconscious During the summer of 1921 D. H. Law organized the seizure of 1,000 copies of The rence sat among the roots of trees at Eber- Rainbow on grounds of obscenity. Already steinberg at the edge of the Black Forest — notorious for his elopement with Frieda "between the toes of a tree, forgetting my Weekley-Richtofen, who at the age of self against the ankle of the trunk"—writing thirty-two was the wife of his Romance Fantasia of the Unconscious. He had come Languages professor and the mother of from Taormina to be with his wife who had three children, Lawrence was accused by the been there since early April, attending her critics of producing in this novel "an orgy sick mother. There is little mention of the of sexiness." He keenly felt the unfairness of book in Lawrence's correspondence, either this criticism and raged against the suppres then or later. -

5 Aboutthepennmuseum

NEWS RELEASE Pam Kosty, Public Relations Director 215.898.4045 [email protected] ABOUT THE PENN MUSEUM Founded in 1887, the Penn Museum (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology) is an internationally renowned museum and research institution dedicated to the understanding of cultural diversity and the exploration of the history of humankind. In its 130-year history, the Penn Museum has sent more than 350 research expeditions around the world and collected nearly one million obJects, many obtained directly through its own excavations or anthropological and ethnographic research. Art and Artifacts from across Continents and throughout Time Three gallery floors feature art and artifacts from ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, North and Central America, Asia, Africa, and the ancient Mediterranean World. Special exhibitions drawn both from the Museum’s own collections and brought in on loan enrich the gallery offerings. Ancient Egyptian treasures on display include monumental architectural elements from the Palace of Merenptah, mummies, and a 15-ton granite Sphinx—the largest Sphinx in the Western Hemisphere. Canaan and Ancient Israel features Near East artifacts and looks at the crossroads of cultures in that dynamic region. Worlds Intertwined, a suite of ancient Mediterranean World galleries, features more than 1,400 artifacts from Greece, Etruscan Italy, and the Roman world. The Museum’s Africa Gallery features material from throughout that vast continent, including fine West and Central African masks and instruments and an acclaimed Benin bronze collection from Nigeria, while an adJacent Imagine Africa with the Penn Museum proJect invites visitors to share perspectives and make suggestions for future African exhibitions. -

“I Don't Care for My Other Books, Now”

THE LIBRARY University of California, Berkeley | No. 29 Fall 2013 | lib.berkeley.edu/give Fiat Lux “I don’t care for my other books, now” MARK TWAIN’S AUTOBIOGRAPHY CONTINUED by Benjamin Griffin, Mark Twain Project, Bancroft Library Mark Twain’s complete, uncensored Autobiography was an instant bestseller when the first volume was published in 2010, on the centennial of the author’s death, as he requested. The eagerly-awaited Volume 2 delves deeper into Twain’s life, uncovering the many roles he played in his private and public worlds. Affectionate and scathing by turns, his intractable curiosity and candor are everywhere on view. Like its predecessor, Volume 2 mingles a dia- ry-like record of Mark Twain’s daily thoughts and doings with fragmented and pungent portraits of his earlier life. And, as before, anything which Mark Twain had written but hadn’t, as of 1906–7, found a place to publish yet, might go in: Other autobiographies patiently and dutifully“ follow a planned and undivergent course through gardens and deserts and interesting cities and dreary solitudes, and when at last they reach their appointed goal they are pretty tired—and they The one-hundred-year edition comprises what have been frequently tired during the journey, too. could be called a director’s cut, says editor Ben But this is not that kind of autobiography. This one Griffin. “It hasn’t been cut to size or made to fit is only a pleasure excursion. the requirements of the market or brought into ” continued on page 6-7 line with notions of public decency. -

Y\5$ in History

THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University A5 In partial fulfillment of The Requirements for The Degree Mi ST Master of Arts . Y\5$ In History by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California May, 2016 Copyright by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read The Gargoyles of San Francisco: Medievalist Architecture in Northern California 1900-1940 by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr., and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History at San Francisco State University. <2 . d. rbel Rodriguez, lessor of History Philip Dreyfus Professor of History THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California 2016 After the fire and earthquake of 1906, the reconstruction of San Francisco initiated a profusion of neo-Gothic churches, public buildings and residential architecture. This thesis examines the development from the novel perspective of medievalism—the study of the Middle Ages as an imaginative construct in western society after their actual demise. It offers a selection of the best known neo-Gothic artifacts in the city, describes the technological innovations which distinguish them from the medievalist architecture of the nineteenth century, and shows the motivation for their creation. The significance of the California Arts and Crafts movement is explained, and profiles are offered of the two leading medievalist architects of the period, Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan. -

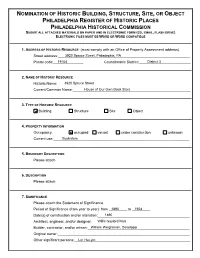

Nomination of Historic Building, Structure, Site, Or Object

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM (CD, EMAIL, FLASH DRIVE) ELECTRONIC FILES MUST BE WORD OR WORD COMPATIBLE 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________3920 Spruce Street, Philadephia, PA ________ Postal code:_______________ 19104 Councilmanic District:__________________________ District 3 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________ 3920 Spruce Street ________ Current/Common Name:________House___________________________________________________ of Our Own Book Store 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:____________________________________________________________ Bookstore ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION Please attach 6. DESCRIPTION Please attach 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1890 to _________1924 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________ 1890 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:_________________________________________________ Willis Gaylord Hale Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________William Weightman, Developer _________ -

Journal of the American Institute of ARCH Itecr·S

Journal of The American Institute of ARCH ITEcr·s PETEil HARRISON November, 1946 Fellowship Honors in The A.I.A. Examinations in Paris-I Architectural Immunity Honoring Louis Sullivan An Editorial by J. Frazer Smith The Dismal Fate of Christopher Renfrew What and Why Is an Industrial Designer? 3Sc PUBLISHED MONTHLY AT THE OCTAGON, WASHINGTON, D. C. UNiVERSITY OF ILLINOJS SMALL HOM ES COUNCIL MUMFORD ~O U SE "JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS NOVEMBER, 1946 VoL. VI, No. 5 Contents Fellowship Honors in The Ameri- Architectural Immunity 225 can Institute of Architects .... 195 By Daniel Paul Higgins By Edgar I. Williams, F.A.I.A. News of the Chapters and Other Honors . 199 Organizations . 228 Examinations in Paris-I .... 200 The Producers' Council. 231 By Huger Elliott The Dismal Fate of Christopher Architects Read and Write: Renfrew . 206 By Robert W. Schmertz "Organic Architecture" . 232 By William G. Purcell Honoring Louis Sullivan By Charles D. Maginnis, Advertising for Architects. 233 F.A.I.A. 208 By 0. H. Murray By William W. Wurster . 209 A Displaced Architect without Chapters of The A.I.A. 213 Documents . 233 By ]. Frazer Smith By Pian Drimmalen What and Why Is an Industrial News of the Educational Field. 234 Designer?. 217 By Philip McConnell The Editor's Asides . 236 ILLUSTRATIONS Tablet marking birth site of Louis H. Sullivan in Boston .. 211 Fur Shop in the Jay Jacob Store, Seattle, Wash .......... 212 George W. Stoddard and Associates, architects Remodeled Country House of Col. Henry W . Anderson, Dinwiddie Co., Va. 221 Duncan Lee, architect Do you know this building? ...... -

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 SWEDENBORGIAN CHURCH Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Swedenborgian Church Other Name/Site Number: Church of the New Jerusalem, Lyon Street Church 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 3200 Washington Street Not for publication: City/Town: San Francisco Vicinity:, State: California County: San Francisco Code: 075 Zip Code: 94115 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: x Building(s): x Public-Local: _ District: _ Public-State: _ Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object:_ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 0 buildings 0 sites 0 structures 0 objects 0 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 0 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 SWEDENBORGIAN CHURCH Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Commartslectures00connrich.Pdf

of University California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California University History Series Betty Connors THE COMMITTEE FOR ARTS AND LECTURES, 1945-1980: THE CONNORS YEARS With an Introduction by Ruth Felt Interviews Conducted by Marilynn Rowland in 1998 Copyright 2000 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Betty Connors dated January 28, 2001. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism by Matthew Purvis A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020, Matthew Purvis i Abstract This dissertation concerns the relation between eroticism and nationalism in the work of a set of English Canadian artists in the mid-1960s-70s, namely John Boyle, Greg Curnoe, and Joyce Wieland. It contends that within their bodies of work there are ways of imagining nationalism and eroticism that are often formally or conceptually interrelated, either by strategy or figuration, and at times indistinguishable. This was evident in the content of their work, in the models that they established for interpreting it and present in more and less overt forms in some of the ways of imagining an English Canadian nationalism that surrounded them. The dissertation contextualizes the three artists in the terms of erotic art prevalent in the twentieth century and makes a case for them as part of a uniquely Canadian mode of decadence. Constructing my case largely from the published and unpublished writing of the three subjects and how these played against their reception, I have attempted to elaborate their artistic models and processes, as well as their understandings of eroticism and nationalism, situating them within the discourses on English Canadian nationalism and its potentially morbid prospects. Rather than treating this as a primarily cultural or socio-political issue, it is treated as both an epistemic and formal one. -

To Center City: the Evolution of the Neighborhood of the Historicalsociety of Pennsylvania

From "Frontier"to Center City: The Evolution of the Neighborhood of the HistoricalSociety of Pennsylvania THE HISToRICAL SOcIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA found its permanent home at 13th and Locust Streets in Philadelphia nearly 120 years ago. Prior to that time it had found temporary asylum in neighborhoods to the east, most in close proximity to the homes of its members, near landmarks such as the Old State House, and often within the bosom of such venerable organizations as the American Philosophical Society and the Athenaeum of Philadelphia. As its collections grew, however, HSP sought ever larger quarters and, inevitably, moved westward.' Its last temporary home was the so-called Picture House on the grounds of the Pennsylvania Hospital in the 800 block of Spruce Street. Constructed in 1816-17 to exhibit Benjamin West's large painting, Christ Healing the Sick, the building was leased to the Society for ten years. The Society needed not only to renovate the building for its own purposes but was required by a city ordinance to modify the existing structure to permit the widening of the street. Research by Jeffrey A. Cohen concludes that the Picture House's Gothic facade was the work of Philadelphia carpenter Samuel Webb. Its pointed windows and crenellations might have seemed appropriate to the Gothic darkness of the West painting, but West himself characterized the building as a "misapplication of Gothic Architecture to a Place where the Refinement of Science is to be inculcated, and which, in my humble opinion ought to have been founded on those dear and self-evident Principles adopted by the Greeks." Though West went so far as to make plans for 'The early history of the Historical Soiety of Pennsylvania is summarized in J.Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, Hisiory ofPhiladelphia; 1609-1884 (2vols., Philadelphia, 1884), 2:1219-22.