Report of the Commission on the Future of the UC Berkeley Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Published Occasionally by the Friends of the Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley, California 94720

PUBLISHED OCCASIONALLY BY THE FRIENDS OF THE BANCROFT LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94720 No. J4 February 1^80 In the beginning - wet who have beginnings, Bust think in ten end, Juet for thought's sake* - in the beginning was^plaeny failve, as it always does, and we have at once dead Matter, and Energy, or on aide by aids,—in aotive eunJunuLlmi fuieyei-r /"what we* -tic universe of Force and Matter is the dead itflalduyof previous 4 •Bftofa are In the. beginning 1 Matter and Fo4 CAUWPITCA m+Hti \ aautt, thayflntoraot forever^ and are inter-dependent, -fiti xm - ^A^dju^^LJ^ waturlallstie unlv»reO| always, ^. m Lawrence's Manuscript of Fantasia of the Unconscious During the summer of 1921 D. H. Law organized the seizure of 1,000 copies of The rence sat among the roots of trees at Eber- Rainbow on grounds of obscenity. Already steinberg at the edge of the Black Forest — notorious for his elopement with Frieda "between the toes of a tree, forgetting my Weekley-Richtofen, who at the age of self against the ankle of the trunk"—writing thirty-two was the wife of his Romance Fantasia of the Unconscious. He had come Languages professor and the mother of from Taormina to be with his wife who had three children, Lawrence was accused by the been there since early April, attending her critics of producing in this novel "an orgy sick mother. There is little mention of the of sexiness." He keenly felt the unfairness of book in Lawrence's correspondence, either this criticism and raged against the suppres then or later. -

“I Don't Care for My Other Books, Now”

THE LIBRARY University of California, Berkeley | No. 29 Fall 2013 | lib.berkeley.edu/give Fiat Lux “I don’t care for my other books, now” MARK TWAIN’S AUTOBIOGRAPHY CONTINUED by Benjamin Griffin, Mark Twain Project, Bancroft Library Mark Twain’s complete, uncensored Autobiography was an instant bestseller when the first volume was published in 2010, on the centennial of the author’s death, as he requested. The eagerly-awaited Volume 2 delves deeper into Twain’s life, uncovering the many roles he played in his private and public worlds. Affectionate and scathing by turns, his intractable curiosity and candor are everywhere on view. Like its predecessor, Volume 2 mingles a dia- ry-like record of Mark Twain’s daily thoughts and doings with fragmented and pungent portraits of his earlier life. And, as before, anything which Mark Twain had written but hadn’t, as of 1906–7, found a place to publish yet, might go in: Other autobiographies patiently and dutifully“ follow a planned and undivergent course through gardens and deserts and interesting cities and dreary solitudes, and when at last they reach their appointed goal they are pretty tired—and they The one-hundred-year edition comprises what have been frequently tired during the journey, too. could be called a director’s cut, says editor Ben But this is not that kind of autobiography. This one Griffin. “It hasn’t been cut to size or made to fit is only a pleasure excursion. the requirements of the market or brought into ” continued on page 6-7 line with notions of public decency. -

U C Berkeley 2009-2019 Capital Financial Plan

U C BERKELEY 2009-2019 CAPITAL FINANCIAL PLAN NOVEMBER 2009 UC BERKELEY 2009-2019 CAPITAL FINANCIAL PLAN UC BERKELEY 2009-2019 CAPITAL FINANCIAL PLAN CONTENTS Preface Executive Overview 1 Goals & Priorities 3 Life Safety 4 Campus Growth & New Initiatives 6 Intellectual Community 8 Campus Environment 9 Capital Renewal 10 Operation & Maintenance 11 Sustainable Campus 12 Capital Approval Process 15 Capital Resources 17 State Funds 19 Gift Funds 21 Campus Funds 22 Capital Program 2009-2019 25 Project Details 35 UC BERKELEY 2009-2019 CAPITAL FINANCIAL PLAN PREFACE In March 2008, The Regents authorized the ‘pilot phase’ of a major reconfiguration of the capital projects approval process: the pilot phase would entail an initial test of the redesign in order to examine its logistics and impacts, prior to full implementation. In general, the new process would delegate much more authority to the campus for project approval, and would limit project-specific review by The Regents to very large and complex projects. Each campus would prepare a set of ‘framework’ plans that outline its capital investment strategy and physical design approach. Once those plans are approved by The Regents, then as long as a project meets certain thresholds, and conforms to the framework plans, it could be approved by the Chancellor, subject to a 15 day review by OP. One of these thresholds is dollar value: the currently proposed figure is $60 million or less. The framework plans for Berkeley include 3 documents: • The 2020 Long Range Development Plan provides a land use policy framework, within which projects can be prioritized and planned. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Decolonizing Being, Knowledge, and Power: Youth Activism in California at the Turn of the 21st Century Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1g51b118 Author Banales, Samuel Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Decolonizing Being, Knowledge, and Power: Youth Activism in California at the Turn of the 21st Century By Samuel Bañales A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California at Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Charles L. Briggs, chair Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes Professor Nelson Maldonado-Torres Fall 2012 Copyright © by Samuel Bañales 2012 ABSTRACT Decolonizing Being, Knowledge, and Power: Youth Activism in California at the Turn of the 21st Century by Samuel Bañales Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California at Berkeley Professor Charles L. Briggs, chair By focusing on the politics of age and (de)colonization, this dissertation underscores how the oppression of young people of color is systemic and central to society. Drawing upon decolonial thought, including U.S. Third World women of color, modernity/coloniality, decolonial feminisms, and decolonizing anthropology scholarship, this dissertation is grounded in the activism of youth of color in California at the turn of the 21st century across race, class, gender, sexuality, and age politics. I base my research on two interrelated, sequential youth movements that I argue were decolonizing: the various walkouts organized by Chican@ youth during the 1990s and the subsequent multi-ethnic "No on 21" movement (also known as the "youth movement") in 2000. -

Commartslectures00connrich.Pdf

of University California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California University History Series Betty Connors THE COMMITTEE FOR ARTS AND LECTURES, 1945-1980: THE CONNORS YEARS With an Introduction by Ruth Felt Interviews Conducted by Marilynn Rowland in 1998 Copyright 2000 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Betty Connors dated January 28, 2001. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Documenting the Biotechnology Industry in the San Francisco Bay Area

Documenting the Biotechnology Industry In the San Francisco Bay Area Robin L. Chandler Head, Archives and Special Collections UCSF Library and Center for Knowledge Management 1997 1 Table of Contents Project Goals……………………………………………………………………….p. 3 Participants Interviewed………………………………………………………….p. 4 I. Documenting Biotechnology in the San Francisco Bay Area……………..p. 5 The Emergence of An Industry Developments at the University of California since the mid-1970s Developments in Biotech Companies since mid-1970s Collaborations between Universities and Biotech Companies University Training Programs Preparing Students for Careers in the Biotechnology Industry II. Appraisal Guidelines for Records Generated by Scientists in the University and the Biotechnology Industry………………………. p. 33 Why Preserve the Records of Biotechnology? Research Records to Preserve Records Management at the University of California Records Keeping at Biotech Companies III. Collecting and Preserving Records in Biotechnology…………………….p. 48 Potential Users of Biotechnology Archives Approaches to Documenting the Field of Biotechnology Project Recommendations 2 Project Goals The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Library & Center for Knowledge Management and the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) are collaborating in a year-long project beginning in December 1996 to document the impact of biotechnology in the Bay Area. The collaborative effort is focused upon the development of an archival collecting model for the field of biotechnology to acquire original papers, manuscripts and records from selected individuals, organizations and corporations as well as coordinating with the effort to capture oral history interviews with many biotechnology pioneers. This project combines the strengths of the existing UCSF Biotechnology Archives and the UCB Program in the History of the Biological Sciences and Biotechnology and will contribute to an overall picture of the growth and impact of biotechnology in the Bay Area. -

Adjustments to 2020-21 Capital Outlay Proposal

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA BERKELEY • DAVIS • IRVINE • LOS ANGELES • MERCED • RIVERSIDE • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO SANTA BARBARA • SANTA CRUZ EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT— OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER 1111 Franklin Street, 6th Floor Oakland, California 94607-5200 510/987-9029 April 7, 2020 The Honorable Holly J. Mitchell Chair, Senate Budget and Fiscal Review Committee State Capitol Sacramento, CA 95814 The Honorable Phil Ting Chair, Assembly Committee on Budget State Capitol Sacramento, CA 95814 Ms. Keely Bosler Director of Finance State Capitol, Room 1145 Sacramento, CA 95814 Dear Senator Mitchell, Assembly Member Ting, and Director Bosler: On August 30, 2019 in accordance with Sections 92493 through 92496 of the Education Code, the University of California submitted for your review and approval the University’s 2020-21 State Capital Outlay proposal totaling $551.4 million. UC submitted detailed information on the proposal’s $300 million 2020-21 UC State Seismic Program on January 13, 2020. Based on these submissions the Department of Finance issued a preliminary approval for UC’s State Capital Outlay proposal on February 14, 2020. With Public Preschool, K-12, and College Health and Safety Bond Act of 2020 (Proposition 13) not passing, the University is requesting some adjustments to its 2020-21 State Capital Outlay proposal. As originally proposed, the $80 million 2020-21 Planning for Future State Capital Outlay program would fund preliminary plans for critical high priority State-eligible major capital projects. With the exception of the San Diego campus’ Revelle College Seismic project, these projects relied on funding from Proposition 13. Accordingly, the University is proposing the revisions to the 2020-21 State Capital Outlay proposal as discussed as follows. -

Campus Parking Map

Campus Parking Map 1 2 3 4 5 University of Mediterranean California Botanical Garden of PARKING DESIGNATION Human Garden Asian Old Roses Bicycle Dismount Zone Genome Southern Australasian South 84 Laboratory Julia African American (M-F 8am-6pm) Morgan New World Central Campus permit Rd Hall C vin Desert al 74 C Herb Campus building 86 83 Garden F Faculty/staff permit Cycad & Chinese Palm Medicinal Garden Herb Construction area 85 Garden S Student permit Miocene Eastern Mexican/ 85B Central Forest North P Botanical American American a Visitor Information n Disabled (DP) parking Strawberry Garden o Botanical r Entrance Lot Mather Californian a Redwood Garden m Entrance ic Grove Emergency Phone P Public Parking (fee required)** A l l P A i a SSL F P H V a c r No coins needed - Dial 9-911 or 911e Lower T F H e Lot L r Gaus e i M Motorcycle permit s W F a Mathematical r Molecular e y SSL H ial D R n Campus parking lot Sciences nn Foundry d a Upper te National 73 d en r Research C o RH Lot Center for J Residence Hall permit Institute r Electron Lo ire Tra e Permit parking street F i w n l p Microscopy er 66 Jorda p 67 U R Restricted 72 3 Garage entrance 62 MSRI P H Hill Area permit Parking 3 Garage level designation Only Grizzly 3 77A rrace Peak CP Carpool parking permit (reserved until 10 am) Te Entrance Coffer V Dam One way street C 31 y H F 2 Hill 77 Lot a P ce W rra Terrace CS Te c CarShare Parking 69 i Streetm Barrier V e 1 a P rrac Lots r Te o n a V Visitor Parking on-campus P V Lawrence P East Bicycle Parking - Central Campus Lot 75A -

Sample Acknowledgments, Donor Stewardship, University Relations, UC Berkeley

Sample Acknowledgments, Donor Stewardship, University Relations, UC Berkeley The Chancellor’s acknowledgement program responds to outright gifts and pledges of $25,000+ and pledge payments of $100,000+. MENU: 1. Menu 2. Hewlett Chair & new Builders of Berkeley donors 3. Fellowship (named fellowship fund) 4. Incentive Awards Program (large-scale scholarship program) 5. Scholarship/Condolence (named scholarship fund) 6. Cal Fund (campuswide unrestricted giving) 7. Class gift for Sather Gate renovation (reunion class project) 8. multi-interest donor with various designations 9. Law school (unit-specific unrestricted giving) 10. Engineering school (unit-specific unrestricted giving) 11. Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (specific research project) 12. Library (capital project) 13. College of Letters & Science (division designation) (anonymity) 14. Pacific Film Archive & BAM/PFA new building update (capital project) 15. Cal Performances (performance sponsorship) 16. Athletics (multiple sports) Dear Mr. Marver: It is my great pleasure to acknowledge your magnificent Hewlett-matched pledge to the University, and to the Graduate School of Public Policy in particular. This exceptional philanthropic commitment perfectly reflects your steadfast devotion to the school. Thank you so much for establishing the James D. Marver Chair in Public Policy, which, I understand, will support the work of a distinguished faculty member doing research in the area of early childhood education policy. Thank you, too, for your years of service on the GSPP Advisory Board, with particular thanks for agreeing this year to serve as chair. I also would like to welcome you to your new status as a Builder of Berkeley. Builders are a special group of historic and current donors whose lifetime giving totals $1 million or more. -

B a N C R O F T I a N a Published Occasionally by the Friends of the Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley, Califo

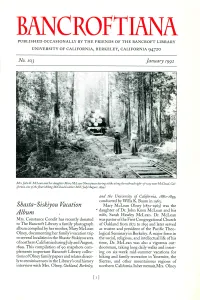

BANCROFTIANA PUBLISHED OCCASIONALLY BY THE FRIENDS OF THE BANCROFT LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 9472O No. IOJ January 1992 Mrs. John K. McLean and her daughter Mary McLean Olney pause during a hike along the railroad right-of-way nearMcCloud, Cal ifornia, site of the flourishing McCloud Lumber Mill (July/August, 1899). and the University of California, 1880-18%, conducted by Willa K. Baum in 1963. Shasta-Siskiyou Vacation Mary McLean Olney (1872-1965) was the daughter of Dr. John Knox McLean and his Album wife, Sarah Hawley McLean. Dr. McLean Mrs. Constance Condit has recently donated was pastor of the First Congregational Church to The Bancroft Library a family photograph of Oakland from 1872 to 1895 an<^ later served album compiled by her mother, Mary McLean as trustee and president of the Pacific Theo Olney, documenting her family's vacation trip logical Seminary in Berkeley. A major force in to several localities in the Shasta-Siskiyou area the social, religious, and intellectual life of his of northern California during July and August, time, Dr. McLean was also a vigorous out- 1899. This compilation of 90 snapshots com doorsman, taking long daily walks and insist plements important Bancroft Library collec ing on six-week mid-summer vacations for tions of Olney family papers and relates direct hiking and family recreation in Yosemite, the ly to reminiscences in the Library's oral history Sierras, and other mountainous regions of interview with Mrs. Olney, Oakland, Berkeley,norther n California. In her memoir, Mrs. Olney [1] describes the Yosemite jaunts and also several historian Ernst Kantorowicz who "brought childhood trips to the Mount Shasta area me to a new vision of the creative spirit and the of Jess's collages will be on display for the first and business associates. -

Admitted Student Packet

Admitted Student Packet Table of Contents Information for Newly Admitted Students GSPP Student Services Staff…………………………………………….Page 1 Important Dates……………………………………………………………Page 2 FAQs………………………………………………………………………..Page 2 Housing……………………………………………………………………..Page 3 Financing Your Graduate Education…………………………………….Page 4-5 Financial Aid………………………………………………………………..Page 5 Registration Fees………………………………………………………….Page 6 Graduate Student Assistantships………………………………………..Page 7-12 Undocumented Student Programs and Resources……………………Page 13 Resources for International Students……………………………………Page 14 Spring Events for Newly Admitted Berkeley, CA – April 6, 2018……………………………………………..Page 15 Washington, D.C. – March 29, 2018…………………………………….Page 16 Graduate Division Welcome and Graduate Student Handbook……………………………Page 17-33 Residency Office Residency Cheat Sheet and FAQs……………………………………...Page 34-35 INFORMATION FOR NEWLY ADMITTED STUDENTS Congratulations on your admission! We hope that you decide to join us at GSPP this fall. As you are making your decision, we hope these documents will provide you with helpful information and resources. GSPP STUDENT SERVICES STAFF CONTACT INFORMATION For questions regarding school policies, For questions regarding career services, procedures, and GSPP fellowships: internships, and alumni relations: Martha Chavez Cecille Cabacungan Senior Assistant Dean for Academic Managing Director of Career & Alumni Programs and Dean of Students Services & PhD Admissions Advisor Phone: 510-643-4266 Phone: 510-642-1303 E-mail: [email protected] -

UC Berkeley 17/18 Abschlussbericht

UC Berkeley 17/18 Abschlussbericht Auf den folgenden Seiten möchte ich über meine zwei Semester an der University of California, Berkeley berichten und zukünftigen Austauschstudenten nützliche Tipps und Tricks zur Vorbereitung auf den Aufenthalt in Berkeley geben. Ich studiere Nordamerikastudien an der Freien Universität Berlin und habe mich durch den Direktaustausch der FU für ein Auslandsjahr im 5. und 6. Semester meines Bachelors beworben. Beim University of California System kommt man nach erfolgreicher Nominierung der FU nochmal in ein kleineres Bewerbungsverfahren, in dem der Campus bestimmt wird. Wer über die FU nach Berkeley gehen will, muss sich somit erstmal für das ganze UC System bewerben und nicht auf einen bestimmten Campus. Die interne Bewerbung ist nach der umfangreichen für den Direktaustausch relativ kurz und kein Grund zur Sorge. Die Zusage über meinen Direktaustauschplatz kam von der FU im Dezember, dass es die UC Berkeley wird wusste ich ca. Ende Februar. Das Fall Semester fängt in Berkeley schon Mitte August an, aber ich hatte trotzdem noch genügend Zeit zur Vorbereitung. Zur Visabeschaffung braucht man das DS-2019 Formular, welches man aus Kalifornien zugeschickt bekommt, und einen Termin in der amerikanischen Botschaft. Dies ist mit einigen Kosten verbunden und garantiert nicht, dass ein Visum gewährt wird. Es muss außerdem ein Nachweis über ausreichende Finanzen für den Auslandsaufenthalt bei der University of California eingereicht werden. Der Stress um die Organisation des Auslandsaufenthalts kann bewältigt werden, wenn man wichtige Termine im Auge behält und sich mit seinen Kommilitonen austauscht. Bei mir, wie bei den meisten, hat eigentlich alles problemlos geklappt und viele Sorgen waren unnötig.