11 Stellar Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X-Ray Sun SDO 4500 Angstroms: Photosphere

ASTR 8030/3600 Stellar Astrophysics X-ray Sun SDO 4500 Angstroms: photosphere T~5000K SDO 1600 Angstroms: upper photosphere T~5x104K SDO 304 Angstroms: chromosphere T~105K SDO 171 Angstroms: quiet corona T~6x105K SDO 211 Angstroms: active corona T~2x106K SDO 94 Angstroms: flaring regions T~6x106K SDO: dark plasma (3/27/2012) SDO: solar flare (4/16/2012) SDO: coronal mass ejection (7/2/2012) Aims of the course • Introduce the equations needed to model the internal structure of stars. • Overview of how basic stellar properties are observationally measured. • Study the microphysics relevant for stars: the equation of state, the opacity, nuclear reactions. • Examine the properties of simple models for stars and consider how real models are computed. • Survey (mostly qualitatively) how stars evolve, and the endpoints of stellar evolution. Stars are relatively simple physical systems Sound speed in the sun Problem of Stellar Structure We want to determine the structure (density, temperature, energy output, pressure as a function of radius) of an isolated mass M of gas with a given composition (e.g., H, He, etc.) Known: r Unknown: Mass Density + Temperature Composition Energy Pressure Simplifying assumptions 1. No rotation à spherical symmetry ✔ For sun: rotation period at surface ~ 1 month orbital period at surface ~ few hours 2. No magnetic fields ✔ For sun: magnetic field ~ 5G, ~ 1KG in sunspots equipartition field ~ 100 MG Some neutron stars have a large fraction of their energy in B fields 3. Static ✔ For sun: convection, but no large scale variability Not valid for forming stars, pulsating stars and dying stars. 4. -

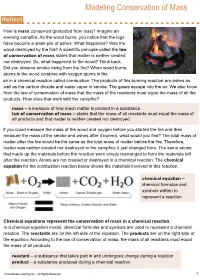

Modeling Conservation of Mass

Modeling Conservation of Mass How is mass conserved (protected from loss)? Imagine an evening campfire. As the wood burns, you notice that the logs have become a small pile of ashes. What happened? Was the wood destroyed by the fire? A scientific principle called the law of conservation of mass states that matter is neither created nor destroyed. So, what happened to the wood? Think back. Did you observe smoke rising from the fire? When wood burns, atoms in the wood combine with oxygen atoms in the air in a chemical reaction called combustion. The products of this burning reaction are ashes as well as the carbon dioxide and water vapor in smoke. The gases escape into the air. We also know from the law of conservation of mass that the mass of the reactants must equal the mass of all the products. How does that work with the campfire? mass – a measure of how much matter is present in a substance law of conservation of mass – states that the mass of all reactants must equal the mass of all products and that matter is neither created nor destroyed If you could measure the mass of the wood and oxygen before you started the fire and then measure the mass of the smoke and ashes after it burned, what would you find? The total mass of matter after the fire would be the same as the total mass of matter before the fire. Therefore, matter was neither created nor destroyed in the campfire; it just changed form. The same atoms that made up the materials before the reaction were simply rearranged to form the materials left after the reaction. -

Law of Conversation of Energy

Law of Conservation of Mass: "In any kind of physical or chemical process, mass is neither created nor destroyed - the mass before the process equals the mass after the process." - the total mass of the system does not change, the total mass of the products of a chemical reaction is always the same as the total mass of the original materials. "Physics for scientists and engineers," 4th edition, Vol.1, Raymond A. Serway, Saunders College Publishing, 1996. Ex. 1) When wood burns, mass seems to disappear because some of the products of reaction are gases; if the mass of the original wood is added to the mass of the oxygen that combined with it and if the mass of the resulting ash is added to the mass o the gaseous products, the two sums will turn out exactly equal. 2) Iron increases in weight on rusting because it combines with gases from the air, and the increase in weight is exactly equal to the weight of gas consumed. Out of thousands of reactions that have been tested with accurate chemical balances, no deviation from the law has ever been found. Law of Conversation of Energy: The total energy of a closed system is constant. Matter is neither created nor destroyed – total mass of reactants equals total mass of products You can calculate the change of temp by simply understanding that energy and the mass is conserved - it means that we added the two heat quantities together we can calculate the change of temperature by using the law or measure change of temp and show the conservation of energy E1 + E2 = E3 -> E(universe) = E(System) + E(Surroundings) M1 + M2 = M3 Is T1 + T2 = unknown (No, no law of conservation of temperature, so we have to use the concept of conservation of energy) Total amount of thermal energy in beaker of water in absolute terms as opposed to differential terms (reference point is 0 degrees Kelvin) Knowns: M1, M2, T1, T2 (Kelvin) When add the two together, want to know what T3 and M3 are going to be. -

Stars IV Stellar Evolution Attendance Quiz

Stars IV Stellar Evolution Attendance Quiz Are you here today? Here! (a) yes (b) no (c) my views are evolving on the subject Today’s Topics Stellar Evolution • An alien visits Earth for a day • A star’s mass controls its fate • Low-mass stellar evolution (M < 2 M) • Intermediate and high-mass stellar evolution (2 M < M < 8 M; M > 8 M) • Novae, Type I Supernovae, Type II Supernovae An Alien Visits for a Day • Suppose an alien visited the Earth for a day • What would it make of humans? • It might think that there were 4 separate species • A small creature that makes a lot of noise and leaks liquids • A somewhat larger, very energetic creature • A large, slow-witted creature • A smaller, wrinkled creature • Or, it might decide that there is one species and that these different creatures form an evolutionary sequence (baby, child, adult, old person) Stellar Evolution • Astronomers study stars in much the same way • Stars come in many varieties, and change over times much longer than a human lifetime (with some spectacular exceptions!) • How do we know they evolve? • We study stellar properties, and use our knowledge of physics to construct models and draw conclusions about stars that lead to an evolutionary sequence • As with stellar structure, the mass of a star determines its evolution and eventual fate A Star’s Mass Determines its Fate • How does mass control a star’s evolution and fate? • A main sequence star with higher mass has • Higher central pressure • Higher fusion rate • Higher luminosity • Shorter main sequence lifetime • Larger -

Stellar Structure and Evolution

Lecture Notes on Stellar Structure and Evolution Jørgen Christensen-Dalsgaard Institut for Fysik og Astronomi, Aarhus Universitet Sixth Edition Fourth Printing March 2008 ii Preface The present notes grew out of an introductory course in stellar evolution which I have given for several years to third-year undergraduate students in physics at the University of Aarhus. The goal of the course and the notes is to show how many aspects of stellar evolution can be understood relatively simply in terms of basic physics. Apart from the intrinsic interest of the topic, the value of such a course is that it provides an illustration (within the syllabus in Aarhus, almost the first illustration) of the application of physics to “the real world” outside the laboratory. I am grateful to the students who have followed the course over the years, and to my colleague J. Madsen who has taken part in giving it, for their comments and advice; indeed, their insistent urging that I replace by a more coherent set of notes the textbook, supplemented by extensive commentary and additional notes, which was originally used in the course, is directly responsible for the existence of these notes. Additional input was provided by the students who suffered through the first edition of the notes in the Autumn of 1990. I hope that this will be a continuing process; further comments, corrections and suggestions for improvements are most welcome. I thank N. Grevesse for providing the data in Figure 14.1, and P. E. Nissen for helpful suggestions for other figures, as well as for reading and commenting on an early version of the manuscript. -

Key Concepts: Conservation of Mass, Momentum, Energy Fluid: a Material

Key concepts: Conservation of mass, momentum, energy Fluid: a material that deforms continuously and permanently under the application of a shearing stress, no matter how small. Fluids are either gases or liquids. (Under very specialized conditions, a phase of intermediate properties can be stable, but we won’t consider that possibility.) In liquids, the molecules are relatively closely spaced, allowing the magnitude of their (attractive, electrically-based) interaction energy to be of the same magnitude as their kinetic energy. As a result, they exist as a loose collection of clusters. In gases, the molecules are much more widely separated, so the kinetic energy (at a given temperature, identical to that in the liquid) is far greater than the interaction energy (much less than in the liquid), and molecule do not form clusters. In a liquid, the molecules themselves typically occupy a few percent of the total space available; in a gas, they occupy a few thousandths of a percent. Nevertheless, for our purposes, all fluids are considered to be continua (no voids or holes).The absence of significant intermolecular attraction allows gases to fill whatever volume is available to them, whereas the presence of such attraction in liquids prevents them from doing so. The attractive forces in liquid water are unusually strong, compared to other liquids. Properties of Fluids: m Density is mass/volume: ρ = . The density of liquid water is V 3 o −3 3 ~1.0 kg/m ; that of air at 20 C is ~1.2x10 kg/m . mg W Specific weight is weight/volume: γ = = = ρg V V C:\Adata\CLASNOTE\342\Class Notes\Key concepts_Topic 1.doc 1 γ Specific gravity is density normalized to the density of water: sg..= i γ w V 1 Specific volume is volume/mass: V = = m ρ Bulk modulus or modulus of elasticity is the pressure change per dp dp fractional change in volume or density: E =− = . -

Stellar Coronal Astronomy

Stellar coronal astronomy Fabio Favata ([email protected]) Astrophysics Division of ESA’s Research and Science Support Department – P.O. Box 299, 2200 AG Noordwijk, The Netherlands Giuseppina Micela ([email protected]) INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico G. S. Vaiana – Piazza Parlamento 1, 90134 Palermo, Italy Abstract. Coronal astronomy is by now a fairly mature discipline, with a quarter century having gone by since the detection of the first stellar X-ray coronal source (Capella), and having benefitted from a series of major orbiting observing facilities. Several observational charac- teristics of coronal X-ray and EUV emission have been solidly established through extensive observations, and are by now common, almost text-book, knowledge. At the same time the implications of coronal astronomy for broader astrophysical questions (e.g. Galactic structure, stellar formation, stellar structure, etc.) have become appreciated. The interpretation of stellar coronal properties is however still often open to debate, and will need qualitatively new ob- servational data to book further progress. In the present review we try to recapitulate our view on the status of the field at the beginning of a new era, in which the high sensitivity and the high spectral resolution provided by Chandra and XMM-Newton will address new questions which were not accessible before. Keywords: Stars; X-ray; EUV; Coronae Full paper available at ftp://astro.esa.int/pub/ffavata/Papers/ssr-preprint.pdf 1 Foreword 3 2 Historical overview 4 3 Relevance of coronal -

White Dwarfs - Degenerate Stellar Configurations

White Dwarfs - Degenerate Stellar Configurations Austen Groener Department of Physics - Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, USA Quantum Mechanics II May 17, 2010 Abstract The end product of low-medium mass stars is the degenerate stellar configuration called a white dwarf. Here we discuss the transition into this state thermodynamically as well as developing some intuition regarding the role of quantum mechanics in this process. I Introduction and Stellar Classification present at such high temperatures are small com- pared with the kinetic (thermal) energy of the parti- It is widely believed that the end stage of the low or cles. This assumption implies a mixture of free non- intermediate mass star is an extremely dense, highly interacting particles. One may also note that the pres- underluminous object called a white dwarf. Obser- sure of a mixture of different species of particles will vationally, these white dwarfs are abundant (∼ 6%) be the sum of the pressures exerted by each (this is in the Milky Way due to a large birthrate of their pro- where photon pressure (PRad) will come into play). genitor stars coupled with a very slow rate of cooling. Following this logic we can express the total stellar Roughly 97% of all stars will meet this fate. Given pressure as: no additional mass, the white dwarf will evolve into a cold black dwarf. PT ot = PGas + PRad = PIon + Pe− + PRad (1) In this paper I hope to introduce a qualitative de- scription of the transition from a main-sequence star At Hydrostatic Equilibrium: Pressure Gradient = (classification which aligns hydrogen fusing stars Gravitational Pressure. -

Chapter 15 - Fluid Mechanics Thursday, March 24Th

Chapter 15 - Fluid Mechanics Thursday, March 24th •Fluids – Static properties • Density and pressure • Hydrostatic equilibrium • Archimedes principle and buoyancy •Fluid Motion • The continuity equation • Bernoulli’s effect •Demonstration, iClicker and example problems Reading: pages 243 to 255 in text book (Chapter 15) Definitions: Density Pressure, ρ , is defined as force per unit area: Mass M ρ = = [Units – kg.m-3] Volume V Definition of mass – 1 kg is the mass of 1 liter (10-3 m3) of pure water. Therefore, density of water given by: Mass 1 kg 3 −3 ρH O = = 3 3 = 10 kg ⋅m 2 Volume 10− m Definitions: Pressure (p ) Pressure, p, is defined as force per unit area: Force F p = = [Units – N.m-2, or Pascal (Pa)] Area A Atmospheric pressure (1 atm.) is equal to 101325 N.m-2. 1 pound per square inch (1 psi) is equal to: 1 psi = 6944 Pa = 0.068 atm 1atm = 14.7 psi Definitions: Pressure (p ) Pressure, p, is defined as force per unit area: Force F p = = [Units – N.m-2, or Pascal (Pa)] Area A Pressure in Fluids Pressure, " p, is defined as force per unit area: # Force F p = = [Units – N.m-2, or Pascal (Pa)] " A8" rea A + $ In the presence of gravity, pressure in a static+ 8" fluid increases with depth. " – This allows an upward pressure force " to balance the downward gravitational force. + " $ – This condition is hydrostatic equilibrium. – Incompressible fluids like liquids have constant density; for them, pressure as a function of depth h is p p gh = 0+ρ p0 = pressure at surface " + Pressure in Fluids Pressure, p, is defined as force per unit area: Force F p = = [Units – N.m-2, or Pascal (Pa)] Area A In the presence of gravity, pressure in a static fluid increases with depth. -

A Teaching-Learning Module on Stellar Structure and Evolution

EPJ Web of Conferences 200, 01017 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/201920001017 ISE2A 2017 A teaching-learning module on stellar structure and evolution Silvia Galano1, Arturo Colantonio2, Silvio Leccia3, Emanuella Puddu4, Irene Marzoli1 and Italo Testa5 1 Physics Division, School of Science and Technology, University of Camerino, Via Madonna delle Carceri 9, I-62032 Camerino (MC), Italy 2 Liceo Scientifico e delle Scienze Umane “Cantone”, Via Savona, I-80014 Pomigliano d'Arco, Italy 3 Liceo Statale “Cartesio”, Via Selva Piccola 147, I-80014 Giugliano, Italy 4 INAF - Capodimonte Astronomical Observatory of Naples, Salita Moiariello, 16, I-80131 Napoli, Italy 5 Department of Physics “E. Pancini”, “Federico II” University of Napoli, Complesso Monte S.Angelo, Via Cintia, I-80126 Napoli, Italy Abstract. We present a teaching module focused on stellar structure, functioning and evolution. Drawing from literature in astronomy education, we identified three key ideas which are fundamental in understanding stars’ functioning: spectral analysis, mechanical and thermal equilibrium, energy and nuclear reactions. The module is divided into four phases, in which the above key ideas and the physical mechanisms involved in stars’ functioning are gradually introduced. The activities combine previously learned laws in mechanics, thermodynamics, and electromagnetism, in order to get a complete picture of processes occurring in stars. The module was piloted with two intact classes of secondary school students (N = 59 students, 17–18 years old) and its efficacy in addressing students’ misconceptions and wrong ideas was tested using a ten-question multiple choice questionnaire. Results support the effectiveness of the proposed activities. Implications for the teaching of advanced physics topics using stars as a fruitful context are briefly discussed. -

Stellar Evolution Microcosm of Astrophysics

Nature Vol. 278 26 April 1979 Spring books supplement 817 soon realised that they are neutron contrast of the type. In the first half stars. It now seems certain that neutron Stellar of the book there are only a small stars rather than white dwarfs are a number of detailed alterations but later normal end-product of a supernova there are much more substantial explosion. In addition it has been evolution changes, particularly dn chapters 6, 7 realised that sufficiently massive stellar and 8. The book is essentially un remnants will be neither white dwarfs R. J. Tayler changed in length, the addition of new nor neutron stars but will be black material being balanced by the removal holes. Rather surprisingly in view of Stellar Evolution. Second edition. By of speculative or unimportant material. the great current interest in close A. J. Meadows. Pp. 171. (Pergamon: Substantial changes in the new binary stars and mass exchange be Oxford, 1978.) Hardback £7.50; paper edition include the following. A section tween their components, the section back £2.50. has been added on the solar neutrino on this topic has been slightly reduced experiment, the results of which are at in length, although there is a brief THE subject of stellar structure and present the major question mark mention of the possible detection of a evolution is believed to be the branch against the standard view of stellar black hole in Cygnus X-1. of astrophysics which is best under structure. There is a completely revised The revised edition of this book stood. -

Spectra of Individual Stars! • Stellar Spectra Reflect:! !Spectral Type (OBAFGKM)!

Stellar Populations of Galaxies-" 2 Lectures" some of this material is in S&G sec 1.1 " see MBW sec 10.1-10.3 for stellar structure theory- will not cover this! Top level summary! • stars with M<0.9M! have MS-lifetimes>tHubble! 8 • M>10M!are short-lived:<10 years~1torbit! • Only massive stars are hot enough to produce HI–ionizing radiation !! • massive stars dominate the luminosity of a young SSP (simple stellar population)! see 'Stellar Populations in the Galaxy Mould 1982 ARA&A..20, 91! and sec 2 of the "Galaxy Mass! H-R(CMD) diagram of! " review paper by Courteau et al! region near sun! arxiv 1309.3276! H-R is theoretical! CMD is in observed units! (e.g.colors)! 1! Spectra of Individual Stars! • Stellar spectra reflect:! !spectral type (OBAFGKM)! • effective temperature Teff! • chemical (surface )abundance! – [Fe/H]+much more e.g [α/Fe]! – absorp'on)line)strengths)depend)on)Teff)and[Fe/ H]! – surface gravity, log g! – Line width (line broadening)! – yields:size at a given mass! ! – dwarf-giant distinction ! !for GKM stars! • no easyage-parameter! – Except e.g. t<t MS! Luminosity • the structure of a star, in hydrostatic and thermal equilibrium with all energy derived H.Rix! from nuclear reactions, is determined by its 2! mass distribution of chemical elements and spin! Range of Stellar Parameters ! • For stars above 100M! the outer layers are not in stable equilibrium, and the star will begin to shed its mass. Very few stars with masses above 100M are known to exist, ! • At the other end of the mass scale, a mass of about 0.1M!is required to produce core temperatures and densities sufficient to provide a significant amount of energy from nuclear processes.