University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction of Médicinal Leeches Into the West Indies in the Nineteenth Century

A study in médical history: introduction of médicinal leeches into the West Indies in the nineteenth century Roy T. SAWYER Biopharm (UK) Ltd, 2 Bryngwili Road, Hendy, Carms. SA4 1XB (UK) 102364.1027® compuserve.com Fred O. P. HECHTEL School of Biological Sciences, University of Wales, Swansea SA2 8PP (UK) James W. HAGY Department of History, University of Charleston, Charleston, SC 29424 (USA) Emanuela SCACHERI Department of Biotechnology, Pharmacia & Upjohn, Viale Pasteur 10,1-20014 Nerviano, Milano (Italy) Sawyer R. T., Hechtel F. O. P., Hagy J. W. & Scacheri E. 1998. — A study in médical histo ry: introduction of médicinal leeches into the West Indies in the nineteenth century. Zoosystema 20 (3) : 451-470. ABSTRACT Médicinal leeches were not found in the West Indies prior to 1822, but by the turn of the century, a large, aggressive leech abounded on Puerto Rico, St Lucia, Martinique and other islands. The authors conclude that this "Caribbean leech", described as Hirudinaria {Poecilobdella) blanchardi Moore, 1901, is a junior synonym of the "buffalo" leech Hirudinaria manillensis (Lesson, 1842), the médicinal leech of India and neighbouring countries of South-East Asia. The final proof of the true identity of this West Indian leech came from comparison of the nucleotide séquences of the cDNAs of the hirudin polypeptide from leeches from St Lucia and from Bangladesh. The authors présent évidence that this leech arrived from ships carrying labourers from colonial India starting in the mid-1840's. Each of thèse ships were required to have leeches on board for médicinal purposes. KEY WORDS Hirudinea, During this study, the existence of a second introduced leech species in the Hirudinaria, West Indies was unexpectedly discovered, in Guadeloupe. -

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sitaram Asur, B.E., M.Sc. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Prof. Srinivasan Parthasarathy, Adviser Prof. Gagan Agrawal Adviser Prof. P. Sadayappan Graduate Program in Computer Science and Engineering c Copyright by Sitaram Asur 2009 ABSTRACT Data originating from many different real-world domains can be represented mean- ingfully as interaction networks. Examples abound, ranging from gene expression networks to social networks, and from the World Wide Web to protein-protein inter- action networks. The study of these complex networks can result in the discovery of meaningful patterns and can potentially afford insight into the structure, properties and behavior of these networks. Hence, there is a need to design suitable algorithms to extract or infer meaningful information from these networks. However, the challenges involved are daunting. First, most of these real-world networks have specific topological constraints that make the task of extracting useful patterns using traditional data mining techniques difficult. Additionally, these networks can be noisy (containing unreliable interac- tions), which makes the process of knowledge discovery difficult. Second, these net- works are usually dynamic in nature. Identifying the portions of the network that are changing, characterizing and modeling the evolution, and inferring or predict- ing future trends are critical challenges that need to be addressed in the context of understanding the evolutionary behavior of such networks. To address these challenges, we propose a framework of algorithms designed to detect, analyze and reason about the structure, behavior and evolution of real-world interaction networks. -

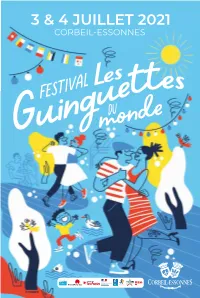

3 & 4 Juillet 2021

3 & 4 JUILLET 2021 CORBEIL-ESSONNES À L’ENTRÉE DU SITE, UNE FÊTE POPULAIRE POUR D’UNE RIVE À L’AUTRE… RE-ENCHANTER NOTRE TERRITOIRE Pourquoi des « guinguettes » ? à établir une relation de dignité Le 3 juillet Le 4 juillet Parce que Corbeil-Essonnes est une avec les personnes auxquelles nous 12h 11h30 ville de tradition populaire qui veut nous adressons. Rappelons ce que le rester. Parce que les guinguettes le mot culture signifie : « les codes, Parade le long Association des étaient des lieux de loisirs ouvriers les normes et les valeurs, les langues, des guinguettes originaires du Portugal situés en bord de rivière et que nous les arts et traditions par lesquels une avons cette chance incroyable d’être personne ou un groupe exprime SAMBATUC Bombos portugais son humanité et les significations Départ du marché, une ville traversée par la Seine et Batucada Bresilienne l’Essonne. qu’il donne à son existence et à son place du Comte Haymont développement ». Le travail culturel 15h Pourquoi « du Monde » ? vers l’entrée du site consiste d’abord à vouloir « faire Parce qu’à Corbeil-Essonnes, 93 Super Raï Band humanité ensemble ». le monde s’est donné rendez-vous, Maghreb brass band 12h & 13h30 108 nationalités s’y côtoient. Notre République se veut fraternelle. 16h15 Aquarela Nous pensons que cela est On ne peut concevoir une humanité une chance. fraternelle sans des personnes libres, Association des Batucada dignes et reconnues comme telles Alors pourquoi une fête des originaires du Portugal dans leur identité culturelle. 15h « guinguettes du monde » Bombos portugais Association Scène à Corbeil-Essonnes ? À travers cette manifestation, 18h Parce que c’est tellement bon de c’est le combat éthique de Et Sonne faire la fête. -

Jocelyne Guilbault, with Gage Averill, Édouard Benoit, and Gregory Rabess. Zouk: World Music in the West Indies. Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 22:08 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Jocelyne Guilbault, with Gage Averill, Édouard Benoit, and Gregory Rabess. Zouk: World Music in the West Indies. Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993. xxv, 279 pp., compact disc included. ISBN 0-226-31041-8 (hardcover), ISBN 0-226-31042-6 (paperback) Robert Witmer Numéro 15, 1995 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014408ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014408ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce compte rendu Witmer, R. (1995). Compte rendu de [Jocelyne Guilbault, with Gage Averill, Édouard Benoit, and Gregory Rabess. Zouk: World Music in the West Indies. Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993. xxv, 279 pp., compact disc included. ISBN 0-226-31041-8 (hardcover), ISBN 0-226-31042-6 (paperback)]. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, (15), 194–198. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014408ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des des universités canadiennes, 1995 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. -

Coopération Culturelle Caribéenne : Construire Une Coopération Autour Du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel Anaïs Diné

Coopération culturelle caribéenne : construire une coopération autour du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel Anaïs Diné To cite this version: Anaïs Diné. Coopération culturelle caribéenne : construire une coopération autour du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-01730691 HAL Id: dumas-01730691 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01730691 Submitted on 13 Mar 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Sous le sceau de l’Université Bretagne Loire Université Rennes 2 Equipe de recherche ERIMIT Master Langues, cultures étrangères et régionales Les Amériques – Parcours PESO Coopération culturelle caribéenne Construire une coopération autour du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel Anaïs DINÉ Sous la direction de : Rodolphe ROBIN Septembre 2017 0 1 REMERCIEMENTS Je tiens à remercier toutes les personnes avec lesquelles j’ai pu échanger et qui m’ont aidé à la rédaction de ce mémoire. Je remercie tout d’abord mon directeur de recherches Rodolphe Robin pour m’avoir accompagné et soutenu depuis mes premières années à l’Université Rennes 2. Je remercie grandement l’Université Rennes 2 et l’Université de Puerto Rico (UPR) pour la formation et toutes les opportunités qu’elles m’ont offertes. -

Graham Nessler

A Failed Emancipation? The Struggle for Freedom in Hispaniola during the Haitian Revolution, 1789-1809 by Graham Townsend Nessler A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Richard L. Turits, Chair Professor Marlyse Baptista Professor Jean M. Hébrard Professor Rebecca J. Scott Professor Laurent M. Dubois, Duke University © Graham Townsend Nessler, 2011 To my mother and father ii Acknowledgements Almost every winter when I was growing up, our family would travel by car from our home in Bryan/College Station, Texas, to Clemson and Greenville, South Carolina, a journey of approximately one thousand miles. These treks to see extended family for Christmas gave me an appreciation for long journeys, which becomes even stronger when one reaches the finish line. My path to the doctorate in History has likewise entailed long journeys in both geographical and other senses. Though a complete acknowledgement of those who have supported and encouraged me in the five countries where I have studied, taught, researched, written, and presented over the past six years would be almost as long as the work that follows, I offer here a more condensed version that tries to include those who have been especially instrumental in ensuring the success of this project and my graduate studies as a whole. I regret any omissions. Any such list must begin with the five scholars who have overseen this project: Richard Turits, Rebecca Scott, Jean Hébrard, Marlyse Baptista, and Laurent Dubois (Professor of History and Romance Studies at Duke University). -

Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean

Peter Manuel 1 / Introduction Contradance and Quadrille Culture in the Caribbean region as linguistically, ethnically, and culturally diverse as the Carib- bean has never lent itself to being epitomized by a single music or dance A genre, be it rumba or reggae. Nevertheless, in the nineteenth century a set of contradance and quadrille variants flourished so extensively throughout the Caribbean Basin that they enjoyed a kind of predominance, as a common cultural medium through which melodies, rhythms, dance figures, and per- formers all circulated, both between islands and between social groups within a given island. Hence, if the latter twentieth century in the region came to be the age of Afro-Caribbean popular music and dance, the nineteenth century can in many respects be characterized as the era of the contradance and qua- drille. Further, the quadrille retains much vigor in the Caribbean, and many aspects of modern Latin popular dance and music can be traced ultimately to the Cuban contradanza and Puerto Rican danza. Caribbean scholars, recognizing the importance of the contradance and quadrille complex, have produced several erudite studies of some of these genres, especially as flourishing in the Spanish Caribbean. However, these have tended to be narrowly focused in scope, and, even taken collectively, they fail to provide the panregional perspective that is so clearly needed even to comprehend a single genre in its broader context. Further, most of these pub- lications are scattered in diverse obscure and ephemeral journals or consist of limited-edition books that are scarcely available in their country of origin, not to mention elsewhere.1 Some of the most outstanding studies of individual genres or regions display what might seem to be a surprising lack of familiar- ity with relevant publications produced elsewhere, due not to any incuriosity on the part of authors but to the poor dissemination of works within (as well as 2 Peter Manuel outside) the Caribbean. -

Creolization on the Move in Francophone Caribbean Literature

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University World Languages and Cultures Faculty Publications Department of World Languages and Cultures 1-2015 Creolization on the Move in Francophone Caribbean Literature Gladys M. Francis Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/mcl_facpub Part of the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Francis, Gladys M. "Creolization on the Move in Francophone Caribbean Literature." The Oxford Diasporas Programme. Oxford: The University of Oxford (2015): 1-15. http://www.migration.ox.ac.uk/odp/pdfs/ Francis,%20G,%202015%20Creolization%20on%20the%20Move-1.pdf This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of World Languages and Cultures at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages and Cultures Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Working Papers Paper 01, January 2015 Creolization on the Move in Francophone Caribbean Literature Dr Gladys M. Francis This paper is published as part of the Oxford Diasporas Programme (www.migration.ox.ac.uk/odp). The Oxford Diasporas Programme (ODP) is funded by the Leverhulme Trust. ODP does not have an institutional view and does not aim to present one. The views expressed in this document are those of its independent author. Abstract In this paper I explore the particular use of dance and music observed in the writings of Maryse Condé, Ina Césaire, and Gerty Dambury. I examine how their use of orality, oral literature, and the body in movement create complex levels of textuality, meaning, and reading. -

Beyond Créolité and Coolitude, the Indian on the Plantation: Recreolization in the Transoceanic Frame

Middle Atlantic Review of Latin American Studies, 2020 Vol. 4, No. 2, 174-193 Beyond Créolité and Coolitude, the Indian on the Plantation: Recreolization in the Transoceanic Frame Ananya Jahanara Kabir Kings College London [email protected] This essay explores the ways in which Caribbean artists of Indian heritage memorialize the transformation of Caribbean history, demography, and lifeways through the arrival of their ancestors, and their transformation, in turn, by this new space. Identifying for this purpose an iconic figure that I term “the Indian on the Plantation,” I demonstrate how the influential theories of Caribbean identity-formation that serve as useful starting points for explicating the play of memory and identity that shapes Indo-Caribbean artistic praxis—coolitude (as coined by Mauritian author Khal Torabully) and créolité (as most influentially articulated by the Martinican trio of Jean Barnabé, Patrick Chamoiseau, and Raphaël Confiant)—are nevertheless constrained by certain discursive limitations. Unpacking these limitations, I offer instead evidence from curatorial and quotidian realms in Guadeloupe as a lens through which to assess an emergent artistic practice that cuts across Francophone and Anglophone constituencies to occupy the Caribbean Plantation while privileging signifiers of an Indic heritage. Reading these attempts as examples of decreolization that actually suggest an ongoing and unpredictable recreolization of culture, I situate this apparent paradox within a transoceanic heuristic frame that brings -

Prestructuring Multilayer Perceptrons Based on Information-Theoretic

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2011 Prestructuring Multilayer Perceptrons based on Information-Theoretic Modeling of a Partido-Alto- based Grammar for Afro-Brazilian Music: Enhanced Generalization and Principles of Parsimony, including an Investigation of Statistical Paradigms Mehmet Vurkaç Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Vurkaç, Mehmet, "Prestructuring Multilayer Perceptrons based on Information-Theoretic Modeling of a Partido-Alto-based Grammar for Afro-Brazilian Music: Enhanced Generalization and Principles of Parsimony, including an Investigation of Statistical Paradigms" (2011). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 384. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.384 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Prestructuring Multilayer Perceptrons based on Information-Theoretic Modeling of a Partido-Alto -based Grammar for Afro-Brazilian Music: Enhanced Generalization and Principles of Parsimony, including an Investigation of Statistical Paradigms by Mehmet Vurkaç A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical and Computer Engineering Dissertation Committee: George G. Lendaris, Chair Douglas V. Hall Dan Hammerstrom Marek Perkowski Brad Hansen Portland State University ©2011 ABSTRACT The present study shows that prestructuring based on domain knowledge leads to statistically significant generalization-performance improvement in artificial neural networks (NNs) of the multilayer perceptron (MLP) type, specifically in the case of a noisy real-world problem with numerous interacting variables. -

Kesha's 'High Road' Is a “Defiant Reclamation of Lightness”

Kesha’s ‘High Road’ Is a “Defiant Reclamation of Lightness” New Album OUT TODAY via Kemosabe/RCA Records LISTEN HERE Today, Kesha drops her new album ‘High Road’ (Kemosabe/RCA Records), reclaiming her throne as “the badass of pop” (Billboard). A delicious mix of debaucherous odes to living life to the fullest, reflections on self-love, and folk-tinged moments embracing all that makes us human, ‘High Road’ is the GRAMMY-nominated popstar’s most eclectic collection to date. Whether discussing topics of self-identity, free love, best friendship, heartbreak or childhood longing, ‘High Road’ expertly encompasses Kesha’s knack for heartfelt vulnerability, her wild child energy, and oddball sense of humor all with major modern pop integrity. It’s an album about not taking life too seriously, but it is done seriously well. For 'High Road', Kesha enlisted a diverse roster of collaborators / songwriters / producers including John Hill, Dan Reynolds, Stuart Crichton, Jeff Bhasker, Drew Pearson, Brian Wilson, Sturgill Simpson, Nate Ruess, Justin Tranter, Stint, Wrabel, and Pebe Sebert among others to help her make this celebratory chapter of her career a reality. Today’s album release follows last night’s incredible performance of “Resentment” on The Late Late Show with James Corden, and the recent announcement of her forthcoming North American spring tour. ‘High Road’ has already delighted critics, with Stereogum saying it “strikes a believable balance between vulnerability and the bluster she made her name on,” The Independent praising it as “a mature and defiant reclamation of lightness,” and AllMusic calling it “a heady good time”. Album standout tracks like “Tonight” (“100 percent your new night-out anthem” – MTV), “Father Daughter Dance” (“a crushing vocal showcase that no one could have expected” – American Songwriter), “Raising Hell” (feat. -

Music 10378 Songs, 32.6 Days, 109.89 GB

Page 1 of 297 Music 10378 songs, 32.6 days, 109.89 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Ma voie lactée 3:12 À ta merci Fishbach 2 Y crois-tu 3:59 À ta merci Fishbach 3 Éternité 3:01 À ta merci Fishbach 4 Un beau langage 3:45 À ta merci Fishbach 5 Un autre que moi 3:04 À ta merci Fishbach 6 Feu 3:36 À ta merci Fishbach 7 On me dit tu 3:40 À ta merci Fishbach 8 Invisible désintégration de l'univers 3:50 À ta merci Fishbach 9 Le château 3:48 À ta merci Fishbach 10 Mortel 3:57 À ta merci Fishbach 11 Le meilleur de la fête 3:33 À ta merci Fishbach 12 À ta merci 2:48 À ta merci Fishbach 13 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 3:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 14 ’¡¢ÁÔé’ 2:29 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 15 ’¡à¢Ò 1:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 16 ¢’ÁàªÕ§ÁÒ 1:36 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 17 à¨éÒ’¡¢Ø’·Í§ 2:07 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 18 ’¡àÍÕé§ 2:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 19 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 4:00 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 20 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:49 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 21 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 22 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡â€ÃÒª 1:58 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 23 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ÅéÒ’’Ò 2:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 24 Ë’èÍäÁé 3:21 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 25 ÅÙ¡’éÍÂã’ÍÙè 3:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 26 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 2:10 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 27 ÃÒËÙ≤˨ђ·Ãì 5:24 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’…