UK Ngos Against Racism CERD Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three the Hard Way Wilfred Limonious: in Fine Style Alex Bartsch: Covers Maxine Walters: Serious Things a Go Happen

HVW8 BERLIN — HVW8 Gallery Berlin in collaboration with One Love Books presents THREE THE HARD WAY WILFRED LIMONIOUS: IN FINE STYLE ALEX BARTSCH: COVERS MAXINE WALTERS: SERIOUS THINGS A GO HAPPEN Cover illustration from the LP Dance Hall Time by Various Artistes (Scar Face Music, 1986) In Fine Style: The Dancehall Art of Wilfred Limonious, is the first solo exhibition of work by prolific Jamaican illustrator Wilfred Limonious (1949–99) in Germany, and includes reproductions of work from the early 1970s through the mid-1990s, spanning three key phases in his career: his comic strips for the Jamaican newspapers, his illustrations for the publications of JAMAL (the Jamaican Movement for the Advancement of Literacy), and his distinctive artwork for the burgeoning dancehall scene coming out of 1980s Jamaica. The exhibition is curated by Al “Fingers” Newman and Christopher Bateman and is produced by One Love Books with the support of the Limonious Estate, to accompany their book, In Fine Style: The Dancehall Art of Wilfred Limonious, the first study into the artist’s life and work. London-based photographer Alex Bartsch makes his debut at HVW8 Gallery Berlin with photographs from his book, Covers: Retracing Reggae Record Sleeves in London, forthcoming on One Love Books. After researching various reggae LPs and twelve-inches from his record collection, Bartsch has re-photographed fifty sleeves in their original London locations, holding them up at arm’s-length so that they blend in with their surroundings, decades later. Presented in this way, the photographs document the transition of time, with the album cover serving as a window into the past, juxtaposed against today’s backdrop. -

United Reggae Magazine #5

MAGAZINE #6 - March 2011 Lady Saw Maikal X Wayne Smith Wayne Wonder Earl 16 Andrew Tosh Richie Spice INTERVIEW London's Passing Clouds Ken Boothe and Big Youth in Paris Jah Mason and Lyricson in France Reggae Month 2011 EME Awards 2011 United Reggae Mag #6 - March 2011 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS 3 - 21 2/ INTERVIEWS • Richie Spice 23 • Maikal X 28 • Lady Saw 34 • Wayne Smith 37 • Andrew Tosh 43 • Earl 16 47 3/ REVIEWS • The Small Axe Guide to Reggae 68-70 51 • Book Of Job by Richie Spice 52 • Tiger Most Wanted 53 • Heat by Little Roy 54 • Sheya Mission - Nine Signs and Heavy Bliss 55 4/ ARTICLES • In The Spotlight: Bizot Bar Opens, RIDDIM speaks, LEGENDary Eats 57 • Wayne Wonder’s Unplanned Hit 60 5/ PHOTOS • Ken Boothe and Big Youth in Paris 63 • Giddeon Family, Natty and Babylon at London’s Passing Clouds 64 • Reggae Month 2011 66 • EME Awards 2011 69 • Jah Mason and Lyricson in France 72 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com. This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/. Not for resale. United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Any reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. NEWS News 4 18th Annual 9 Mile Music Festival four cans of food. -

1 Introduction: Plato's Challenge

Notes 1 Introduction: Plato’s Challenge 1. A key difference being that Steiner does not consider this move to be a cause for pessimism, but of hope and modern progress. 2. Halliwell is referring here to Aristotle’s displacement of the religious with the secular and to those disposed toward a secular reading of the fifth-cen- tury Attic playwright, Euripides. 3. Steiner is not suggesting that suffering is absent from modernity. His point rather is that as a form of drama, tragedy is particular to the classical Western tradition. He argues, for example, that the death of a Christian hero can be an occasion of sorrow, but not of tragedy because it leads the soul toward justice and resurrection (1961: 332). This move from fatalism toward hope is exemplified by the treatment of tragedy in Dante’s Divine Comedy where all ends well. Steiner’s assertion has been the cause of much debate, as dem- onstrated by Raymond Williams’s provocative text entitled, Modern Tragedy (1966). 4. This is not to suggest that the hero’s decline is simply the result of exter- nal forces. The notion of hamartia—used here to denote a missing of the mark—is suggestive of the fact that the hero is responsible for their suffer- ing, even if their downfall occurs through ignorance, human blindness, or an error of judgment (see Williams on Shame and Necessity (1993)). 5. From this perspective, to benefit from the security and perceived advantages of the “social contract,” “enlightened” rational individuals were required to submit to a common sovereign power and, in so doing, bridle their passions and renounce the “brutish” appetites that comprised their biological psychic condition—the “State of nature.” 6. -

Read Extract

First published in the UK in 2021 by Faber & Faber Limited Bloomsbury House, 74–77 Great Russell Street London, wc1b 3da faberchildrens.co.uk Typeset by M Rules in Mr Eaves This font has been specially chosen to support reading The chapter fonts have been selected to match those used by the artists themselves Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, cr0 4yy All rights reserved Text © Jeffrey Boakye, 2021 Illustrations © Ngadi Smart, 2021 The right of Jeffrey Boayke and Ngadi Smart to be identified as author and illustrator respectively of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978–0–571–36648–4 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Playlist Introduction 5 ‘London Is the Place for Me’ – Lord Kitchener (1948) 15 ‘Let’s Have Another Party’ – Winifred Atwell (1954) 23 ‘No Carnival in Britain’ – Mighty Terror (1954) 29 ‘Sweets for my Sweet’ – The Searchers (1963) 35 ‘Sweet Mother’ – Prince Nico Mbarga (1976) 43 ‘Sonny’s Lettah’ – Linton Kwesi Johnson (1979) 47 ‘Ghost Town’ – The Specials (1981) 55 ‘Pass the Dutchie’ – Musical Youth (1982) 61 ‘Electric Avenue’ – Eddy -

KOLA E-Zine March 2011

KOLA E-ZINE Black Knight Communication http://kolanetwork.wordpress.com March 2011 Issue 41 Articles :- Editorial An inconvenient truth – A Midsomer murder 2 Smiley Culture 3 Elizabeth “Bessie” Coleman 5 Dates to remember for Black History (March) 10 England's smartest family 15 Former Customs & Excise Senior Officer receives New Year's David Victor Emanuel Honour 16 also known as Political Correctness 'Smiley Culture' Don't call animals “it” in 1963 - 2011 the Bible 17 Tories pose with golliwogs in PC stunt 20 What does KOLA mean? 21 KOLA E-Zine March 2011 Issue 4 1 http://kolanetwork.wordpress.com politically correct." I am sure this is not news to any Black and ethnic minority audience member where we continue to search for faces that reflect our own, EDITORIAL only to find them in stereotypical roles of drug dealers and hood rats. However, Mr True May spoke an inconvenient truth that could be a metaphor for the rest of society. An inconvenient truth – A Midsomer murder I don’t know about you, but I found the actions of the Yes society should be more inclusive, but for the program makers of Midsomer murder’s in suspending large part those in control/power probably also producer, Brian True-May, the height of hypocrisy. perceive that these all white bastions they preside over work. His fellow producers or TV network could not have slept walked through these past 14 years and not notice they have only employed one person of colour, a mixed race actress by the name of Indria Ove, an actress with natural blonde tousled hair and green eyes. -

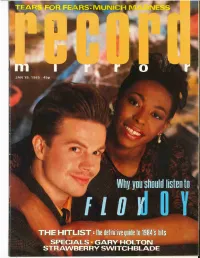

Record-Mirror-1985-0

w. TEAR Why you should listen to fig y' THE HITLIST the definitittuide to 1984's hits SPECIALS* GARY HOLTON STRAWBERRYWorldRadioHistory SWITCHBLADE 2 January 19, 1985 UNCHING IT out with Smiley Culture at the top of the reggae charts is Maxi pPriest and his burning piece of level vibes 'Should l'. A blues dance performer since the age of 14. Maxi learnt his sweet tongued stuff with the Saxon Studio International sound alongside wicked operators like Philip Levi. Now those rhythms are hitting success and Maxi is set to really celebrate with an album 'Can You Feel The Vibes' released in February. UST TO prov that the Irish export more things than Guinness, the band vote 'best newcomers' in the country s leading music paper's poll is releasing a single here on Januar 18. 'Slipway' is the rirst British release for Les Enfants although their debut was a track brought out in Ireland last year. Deric: Lead voc. Is, Ronan O'Hanlon: Guitar, Mich el Cosgrove: Keyboards, Derek yan: Bass, Niall Power: Drums, ent down well supporting Paul Y ung before Christmas and sound 'Ice a cross between Talk Talk and Talking Heads, with a Duran duran pose thrown in for goo measure. Parlez vous Fra cais? NOTHER GIANT step for the medical profession as Dr Calculus takes to the turntables with an unusual, yet Aintriguing, semi-instrumental electro single. RA VING THE critics are Simon Toulson Clarke and Julian Close, 'Programme 7' is already denting the lower reaches ofthe collectively known as Red Box, whose interest in Aboriginal and chart for the Brummie duo, who met by chance in London's BAmerican Indian music forms has led to their truly wonderful Piccadilly. -

'Jafaican' : the Discoursal Embedding of Multicultural London English In

This is a repository copy of The objectification of ‘Jafaican’ : the discoursal embedding of Multicultural London English in the British media. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/93713/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Kerswill, Paul orcid.org/0000-0002-6540-9312 (2014) The objectification of ‘Jafaican’ : the discoursal embedding of Multicultural London English in the British media. In: Androutsopoulos, Jannis, (ed.) The Media and Sociolinguistic Change. Walter De Gruyter , Berlin , 428–455. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Paul Kerswill, York The objectification of ‘Jafaican’. The discoursal embedding of Multicultural London English in the British media1 1 Introduction: Mediatization of new urban youth varieties Since the 1980s, both lay commentators and academic experts have shown an intense interest in apparently new linguistic practices among young people living in multiethnic neighbourhoods in the major cities of northern Europe. Both kinds of observer note that the version of the national language used by these young people is a departure from what is ‘normal’ in that language. -

Jamaica, Home of All Right

Issue No. 12 BRUCE ANDERSON’S RISING TORY STARS BILL KNOTT ON FORAGING FOCUS ON WILLIAM RUSSIA GENERAL SIR PETER WALL SITWELL & CON COUGHLIN WINE AT ROGER BOOTLE ALTITUDE ON TRUMP STANLEY JOHNSON’S RUMBLE IN THE JUNGLE THE NEW Jamaica, ASTON MARTIN THE INTERVIEWS MELANIE C home of All Right MARCELLA DETROIT RITA COOLIDGE £4.95 KATZ ON $7.40 €6.70 SAXON SOUND ¥880 If there had to be only one Toric Chronomètre Manufactured entirely in Switzerland parmigiani.com ATELIER PARMIGIANI 97 Mount Street, Mayfair, London W1K 2TD Tel. +44 20 7495 5172 Parmigiani_HQ • Visual: Toric • Magazine: Boisdale 4 (GB) • Language: English • Issue: 08/12/2017 • Doc size: 420 x 297 mm • Calitho #: 12-17-126733 • AOS #: PF_03180 • EB 08/12/2017 If there had to be only one Toric Chronomètre Manufactured entirely in Switzerland parmigiani.com ATELIER PARMIGIANI 97 Mount Street, Mayfair, London W1K 2TD Tel. +44 20 7495 5172 Parmigiani_HQ • Visual: Toric • Magazine: Boisdale 4 (GB) • Language: English • Issue: 08/12/2017 • Doc size: 420 x 297 mm • Calitho #: 12-17-126733 • AOS #: PF_03180 • EB 08/12/2017 The new Continental GT. Be Extraordinary. The new Continental GT fuel consumption – EU Drive Cycle in mpg (l/100 km): Urban 16.0 (17.7); Innovation and exhilaration in equal measure. Discover more at BentleyMotors.com/Continental Extra Urban 31.7 (8.9); Combined 23.2 (12.2). CO2 Emissions 278 g/km. The name ‘Bentley’ and the ‘B’ in wings device are registered trademarks. © 2018 Bentley Motors Limited. Model shown: Continental GT. Bentley_Boisdale_Life_1105_297x420.indd All Pages 02/05/2018 10:34 The new Continental GT. -

Nichola Smalley Ucl

CONTEMPORARY URBAN VERNACULARS IN RAP, LITERATURE AND IN TRANSLATION IN SWEDEN AND THE UK NICHOLA SMALLEY UCL PHD 1 2 Declaration I, Nichola Smalley confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: ____________________________________________________________ 3 4 Abstract This thesis explores the use of contemporary urban vernaculars in creative writing in Sweden and the UK. Contemporary urban vernaculars can be defined as varieties of informal speech that have emerged in urban areas with high ethnic and linguistic diversity, and have come to index social affiliation and identity. The thesis examines the form these varieties take when represented in selected examples of creative writing including rap lyrics, poetry, prose, drama, and translation. It also looks at the way such varieties progress from one form to another, arguing that there is a translation effect in operation as spoken language is codified through oral and written forms both within, and between, languages. In order to do all this, the study progresses through a number of steps. First it describes the linguistic phenomena in question; identifying potential equivalences between occurrences of these phenomena in Swedish and English. It then investigates the ways these forms of spoken language have found their way into rap, and then literature, as well as exploring the connections and disparities between these creative verbal forms, both in terms of their formal qualities and their social ones. The main literary corpus consists of a small number of works in Swedish published from 2001 to 2008, including a play, poems, short stories and novels. -

King's Research Portal

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/03007766.2018.1471774 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Adams, R. (2019). “Home sweet home, that’s where I come from, where I got my knowledge of the road and the flow from”: Grime music as an expression of identity in postcolonial London. Popular Music & Society, 42(4), 438-455. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2018.1471774 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Dancecult 5(2) Reviews

Reviews Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture Ytasha L. Womack Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2013. ISBN: 978-1-61374-796-4 (paperback) RRP: US $$16.95 (paperback) DOI:10.12801/1947-5403.2013.05.02.08 tobias c. van Veen McGill University (Canada) Following upon her accessible and personable book documenting the transformation of “race” in the late 20th century African American context, Post-Black: How a New Generation is Redefining African American Identity(2010), Ytasha Womack has written a similarly enlightening and readable survey of Afrofuturism. Womack provides several useful definitions of Afrofuturism, notably as “an intersection of imagination, technology, the future, and liberation”, in which “Afrofuturists redefine culture and notions of blackness for today and the future” by combining “elements of science fiction, historical fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy, Afrocentricity, and magic realism with non-Western beliefs” (9). With its first-person narrative, easy-going interview quotes from Afrofuturist artists, musicians, writers and scholars, overview of Afrofuturism’s scholarly history, artistic and musical traditions, and numerous references to past and contemporary Afrofuturist works, the book is useful for newcomers and adherents alike. Womack’s chapters are prefaced by full-page black-and-white comic-style artwork from John Jennings and James Marshall, an added touch that greatly aids in visualizing the futurist hybridity of black identity and technology. Let me not curb my enthusiasm: Ytasha Womack has successfully accomplished the long- overdue and challenging task of writing the first book-length overview of Afrofuturism. Through her concise and self-reflective reportage, Womack has explicated Afrofuturism’s concepts, artists and works with ease and sophistication. -

Dying for Justice

Dying forJustice Edited by Harmit Athwal and Jenny Bourne Dying for Justice Edited by Harmit Athwal and Jenny Bourne Institute of Race Relations Notes and acknowledgements Chapters 1-5 have been written by Harmit Athwal, Jenny Bourne and Frances Webber. Other sections have been written by the authors indicated on each piece. Numerous individual families and their campaigns have, over the years, provided the inspiration and impetus for this report and the IRR’s onging work on the issue. We are also indebted to a host of volunteers, too many to name, who have helped us over the years. But we owe a special debt to Betsy Barkas, Ann Dryden, Trevor Hemmings and Mike Higgs. All pictures are copyright of IRR News unless otherwise specified. Cover: Vigil for Mikey Powell in September 2012. (© Ken Fero/Migrant Media) Pages 42-43: Top row, left-to-right Marcia Rigg and Stephanie Lightfoot-Bennett at a demonstration outside the CPS in August 2014. United Families and Friends annual remembrance procession in October 2013. Middle row, left-to-right Demonstration outside Yarl's Wood removal centre following death of Manuel Bravo in 2005. Demonstration outside Yarl's Wood removal centre following death of Manuel Bravo in 2005. Demonstration outside Harmondsworth removal centre in 2006. Adrienne Makenda Kambana, with Deborah Coles (INQUEST) and friends outside Isleworth Crown Court at the end of the inquest into the death of Jimmy Mubenga in 2013. Birthday vigil for Habib ‘Paps' Ullah in High Wycombe in December 2014. Bottom row, left-to-right Stafford Scott at a demonstration outside the offices of the IPCC in 2012.