Ethnic Minority Radio: Interactions and Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcast and on Demand Bulletin Issue Number 377 29/04/19

Issue 377 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 29 April 2019 Issue number 377 29 April 2019 Issue 377 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 29 April 2019 Contents Introduction 3 Notice of Sanction City News Network (SMC) Pvt Limited 6 Broadcast Standards cases In Breach Sunday Politics BBC 1, 30 April 2017, 11:24 7 Zee Companion Zee TV, 18 January 2019, 17:30 26 Resolved Jeremy Vine Channel 5, 28 January 2019, 09:15 31 Broadcast Licence Conditions cases In Breach Provision of information Khalsa Television Limited 34 In Breach/Resolved Provision of information: Diversity in Broadcasting Various licensees 36 Broadcast Fairness and Privacy cases Not Upheld Complaint by Symphony Environmental Technologies PLC, made on its behalf by Himsworth Scott Limited BBC News, BBC 1, 19 July 2018 41 Complaint by Mr Saifur Rahman Can’t Pay? We’ll Take It Away!, Channel 5, 7 September 2016 54 Complaint Mr Sujan Kumar Saha Can’t Pay? We’ll Take It Away, Channel 5, 7 September 2016 65 Tables of cases Investigations Not in Breach 77 Issue 377 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 29 April 2019 Complaints assessed, not investigated 78 Complaints outside of remit 89 BBC First 91 Investigations List 94 Issue 377 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 29 April 2019 Introduction Under the Communications Act 2003 (“the Act”), Ofcom has a duty to set standards for broadcast content to secure the standards objectives1. Ofcom also has a duty to ensure that On Demand Programme Services (“ODPS”) comply with certain standards requirements set out in the Act2. -

WMCSA Brochure 2016

2016 West Midlands Community Sports Awards Partnership Opportunities The West Midlands Community Sports Awards An inspirational Awards Ceremony recognising and celebrating sporting achievements across the region Organised by the 6 County Sports Partnerships in West Midlands - Sport Birmingham, Sport Across Staffordshire & Stoke on Trent (SASSOT), Herefordshire & Worcestershire, Coventry, Solihull & Warwickshire Sport, Black Country BeActive Partnership and Energize Shropshire, Telford & Wrekin nominate the very best newcomer’s, coaches, community clubs and projects at this high profile, star studded event. This celebration of local community sport recognises the quality and importance of grassroots sport across the region highlighting the commitment of local people and their inspirational journeys. BBC Midlands Today will be broadcasting live on the night linking into BBC Midlands Today News and showing highlight’s the following day. There will also be extensive coverage across the BBC West Midlands Radio network, regional newspapers and social media. 1 Audience Profile Our audience includes sports development professionals and local leaders in sport, health & education sectors, community and voluntary organisations. There will also be influencers in sport across the six County Sports Partnerships, National Governing Bodies and of course our nominees in the following award categories: Unsung Hero – led and coordinated by BBC West Midlands Power of Sport – supported by BBC Local Radio Community Club of the Year Community Coach of the Year -

Data by BBC Region

ESTIMATED OUTCOME OF COUNCIL TAX DEMANDS AND PRECEPTS 2020/21 BY BBC REGION TABLE C Local Requirement Police Precepts Fire Precepts Other Major Precepts (e.g. County) Total Precepts Average Band D Equivalent of which: (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (including Parish / Community) ASC Precept Percentage Percentage Percentage Percentage Percentage Percentage Total Increase / Increase / Increase / Increase / Increase / Increase / Increase / 2019/20 2020/21 (Decrease) 2019/20 2020/21 (Decrease) 2019/20 2020/21 (Decrease) 2019/20 2020/21 (Decrease) 2019/20 2020/21 (Decrease) 2019/20 2020/21 (Decrease) (Decrease) 2020/21 £ p £ p £ p £ p £ p £ p £ p £ p £ p £ p £ p £ p £ p £ p BBC London 1,008.73 1,047.23 3.8% 233.96 243.80 4.2% 8.75 8.90 1.7% 318.13 328.96 3.4% 560.84 581.66 3.7% 1,569.57 1,628.89 3.8% 59.32 17.21 BBC North West 1,256.82 1,303.25 3.7% 200.70 210.68 5.0% 45.45 46.36 2.0% 300.30 315.37 5.0% 546.45 572.41 4.8% 1,803.27 1,875.66 4.0% 72.39 20.17 BBC Yorkshire 1,133.13 1,172.56 3.5% 205.99 214.14 4.0% 69.32 70.69 2.0% 347.37 358.63 3.2% 622.68 643.46 3.3% 1,755.81 1,816.02 3.4% 60.21 14.12 BBC North East & Cumbria 1,260.69 1,308.38 3.8% 201.83 208.85 3.5% 63.18 64.42 2.0% 347.39 360.16 3.7% 612.40 633.43 3.4% 1,873.09 1,941.81 3.7% 68.72 21.42 BBC West Midlands 945.58 979.05 3.5% 191.24 200.68 4.9% 63.94 65.24 2.0% 534.36 556.65 4.2% 789.54 822.57 4.2% 1,735.12 1,801.62 3.8% 66.50 16.93 BBC West 1,104.14 1,149.05 4.1% 223.13 232.51 4.2% 62.20 63.25 1.7% 451.64 469.30 3.9% 736.97 765.06 3.8% 1,841.11 1,914.11 4.0% 73.00 19.44 BBC East 513.04 -

New Report Reveals Public Service Impact of Commercial Radio

May 16, 2011 NEW REPORT REVEALS PUBLIC SERVICE IMPACT OF COMMERCIAL RADIO RadioCentre, the industry body for commercial radio, today (May 16) released a new report, Action Stations: The Output and Impact of Commercial Radio, which highlights the industry’s investment in vital public service broadcasting such as news and information; cultural and social action; community involvement and charitable activities. The report is being backed by a nation-wide advertising campaign on commercial radio, highlighting the valuable contribution the industry makes to communities and local businesses. It follows on from commercial radio’s best–ever haul of 14 Golds at this year’s Sony Radio Academy Awards and record audience reach figures announced last week. The Action Stations report, which is the result of a substantial audit conducted across more than 160 commercial radio stations, shows that on average, some eight and a half hours of public service content are broadcast each week by commercial radio stations. Andrew Harrison, Chief Executive of RadioCentre said: “Commercial radio has been through some big changes in the last few years, with the launch of new national and regional brands offering a genuine alternative to the BBC. However, this report shows that is only part of the story. The vast majority of commercial stations are locally-focused and are still making a vital contribution to their communities by offering real public value. “Commercial radio achieved its biggest ever audience over the last quarter, with the potent combination of national networks and local services proving hugely successful in attracting listeners. This survey shows that these stations not only entertain, but also have a real impact on people’s lives.” The radio advertising campaign, which will be offered to all RadioCentre’s members, emphasises the importance of the stations’ relationships with their listeners, using the theme of ‘commercial radio, your radio’ to promote the notion and importance of a strong, thriving, local and regional commercial radio sector. -

BBC Local Radio, Local News & Current Affairs Quantitative Research

BBC Local Radio, Local News & Current Affairs Quantitative Research August - September 2015 A report by ICM on behalf of the BBC Trust Creston House, 10 Great Pulteney Street, London W1F 9NB [email protected] | www.icmunlimited.com | +44 020 7845 8300 (UK) | +1 212 886 2234 (US) ICM Research Ltd. Registered in England No. 2571387. Registered Address: Creston House, 10 Great Pulteney Street, London W1F 9NB A part of Creston Unlimited BBC Trust Local Services Review, 2015 - Report Contents Executive summary .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Background and methodology ................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Methodology ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Presentation and interpretation of the data ......................................................................... 7 2. BBC Local Radio ...................................................................................................................... 9 2.3 Types of local news and information consumed – unprompted ......................................... 11 2.4 Times of day BBC Local Radio is listened to, tenure with station and hours per week listened .......................................................................................................................................... -

BBC Radio Post-1967

1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Operated by BBC Radio 1 BBC Radio 1 Dance BBC Radio 1 relax BBC 1Xtra BBC Radio 1Xtra BBC Radio 2 BBC Radio 3 National BBC Radio 4 BBC Radio BBC 7 BBC Radio 7 BBC Radio 4 Extra BBC Radio 5 BBC Radio 5 Live BBC Radio Five Live BBC Radio 5 Live BBC Radio Five Live Sports Extra BBC Radio 5 Live Sports Extra BBC 6 Music BBC Radio 6 Music BBC Asian Network BBC World Service International BBC Radio Cymru BBC Radio Cymru Mwy BBC Radio Cymru 2 Wales BBC Radio Wales BBC Cymru Wales BBC Radio Wales BBC Radio Wales BBC Radio Wales BBC Radio Gwent BBC Radio Wales Blaenau Gwent, Caerphilly, Monmouthshire, Newport & Torfaen BBC Radio Deeside BBC Radio Clwyd Denbighshire, Flintshire & Wrexham BBC Radio Ulster BBC Radio Foyle County Derry BBC Northern Ireland BBC Radio Ulster Northern Ireland BBC Radio na Gaidhealtachd BBC Radio nan Gàidheal BBC Radio nan Eilean Scotland BBC Radio Scotland BBC Scotland BBC Radio Orkney Orkney BBC Radio Shetland Shetland BBC Essex Essex BBC Radio Cambridgeshire Cambridgeshire BBC Radio Norfolk Norfolk BBC East BBC Radio Northampton BBC Northampton BBC Radio Northampton Northamptonshire BBC Radio Suffolk Suffolk BBC Radio Bedfordshire BBC Three Counties Radio Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire & North Buckinghamshire BBC Radio Derby Derbyshire (excl. -

BBC English Regions Management Review 2013/14 Management Review 2013/14 – English Regions

BBC English Regions Management Review 2013/14 Management Review 2013/14 – English Regions If you wish to find out more about the BBC’s year – including full financial statements and performance against other public commitment – then please visit: www.bbc.co.uk/annualreport Contents 01 Introduction 02 Two minute summary Front cover 04 Service performance As part of BBC Radio Cumbria’s 40th 11 Future Strategy anniversary, the radio station linked up 11 Contacts with the BBC Philharmonic, BBC Outreach 12 Senior management team and the Cumbria Music Service to create a 13 Heads of regional and local programming Cumbria Community Orchestra and Chorus Management Review 2013/14 – English Regions Management Review 2013/14 – English Regions Controller’s introduction ‘‘ We want to do all we can to play our part in helping all forms of local journalism to flourish not only inside the BBC, but outside it too.’’ Throughout the mayhem of the winter rain, the storms and In the year ahead, our specialist network of political journalists the flood surges audiences depended on our teams for news will report on, aim to make sense of, and seek to engage people and crucial information. It was a strong example of the special in the stories which matter to local communities ahead of next responsibility we have in keeping communities in touch, but year’s General Election. We will reflect the excitement of the it was also another demonstration of the unique, and highly Commonwealth Games and other major sports events. And we prized emotional bond we have with our audiences. -

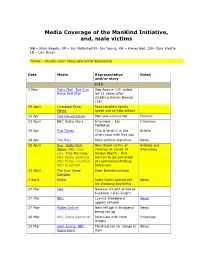

Media Coverage of the Mankind Initiative, And, Male Victims

Media Coverage of the ManKind Initiative, and, male victims MB – Mark Brooks, IM – Ian McNicholl,IY- Ian Young, KB – Kieron Bell, SW- Sara Westle LB – Lori Busch Yellow – denote court cases and initial disclosures Date Media Representative Detail and/or story 2018 3 May Daily Mail, The Sun, Zoe Adams (19) jailed News and Star for 11 years after stabbing Kieran Bewick (18) 29 April Liverpool Echo, Paul Lavelle’s family Metro speak out to help others 26 Apr The Conversation Men are victims too Feature 23 April BBC Radio Worc Interview – Ian Interview McNicholl 19 Apr The Times This is what it is like Article when your wife hits you 18 Apr The Sun Male victims statistics News 16 April Sun, Daily Mail, Alex Skeel victim of Articles and Metro, BBC Five violence at hands of interviews Live, This Morning, Jordan Worth - first BBC Radio Scotland, woman to be convicted BBC Three Counties, of coercive/controlling BBC Breakfast behaviour 13 April The Sun (Dear Dear Deirdre column Deirdre) 7 April Mirror Jodie Owen spared jail News for stabbing boyfriend 29 Mar Mail Nasreen Knight attacked husband Julian knight 27 Mar BBC Lavinia Woodward News appeal refused 27 Mar Wales Online New refuge in Bridgend News being set up 26 Mar BBC Radio Somerset Interview with Mark Interview Brooks 23 Mar Kent online, BBC ManKind call for refuge in News Radio Kent Kent 14-16 Mar Stoke Sentinel, BBC Pete Davegun fundraiser Radio Stoke, Crewe Guardian, Staffs Live 19 Mar Victoria Derbyshire Mark Brooks interview Interview 12 Mar Somerset Live ManKind Initiative appeal -

RISHI SUNAK SARATHA RAJESWARAN a Portrait of Modern Britain Rishi Sunak Saratha Rajeswaran

A PORTRAIT OF MODERN BRITAIN RISHI SUNAK SARATHA RAJESWARAN A Portrait of Modern Britain Rishi Sunak Saratha Rajeswaran Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. We are an educational charity whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas that will deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy. Registered charity no: 1096300. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development. We work in partnership with academics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy outcomes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Trustees Daniel Finkelstein (Chairman of the Board), Richard Ehrman (Deputy Chair), Theodore Agnew, Richard Briance, Simon Brocklebank-Fowler, Robin Edwards, Virginia Fraser, David Frum, Edward Heathcoat Amory, David Meller, Krishna Rao, George Robinson, Robert Rosenkranz, Charles Stewart-Smith and Simon Wolfson About the Authors Rishi Sunak is Head of Policy Exchange’s new Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) Research Unit. Prior to joining Policy Exchange, Rishi worked for over a decade in business, co-founding a firm that invests in the UK and abroad. He is currently a director of Catamaran Ventures, a family-run firm, backing and serving on the boards of various British SMEs. He worked with the Los Angeles Fund for Public Education to use new technology to raise standards in schools. He is a Board Member of the Boys and Girls Club in Santa Monica, California and a Governor of the East London Science School, a new free school based in Newham. -

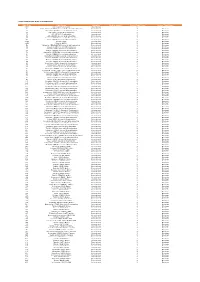

Codes Used in D&M

CODES USED IN D&M - MCPS A DISTRIBUTIONS D&M Code D&M Name Category Further details Source Type Code Source Type Name Z98 UK/Ireland Commercial International 2 20 South African (SAMRO) General & Broadcasting (TV only) International 3 Overseas 21 Australian (APRA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 36 USA (BMI) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 38 USA (SESAC) Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 39 USA (ASCAP) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 47 Japanese (JASRAC) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 48 Israeli (ACUM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 048M Norway (NCB) International 3 Overseas 049M Algeria (ONDA) International 3 Overseas 58 Bulgarian (MUSICAUTOR) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 62 Russian (RAO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 74 Austrian (AKM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 75 Belgian (SABAM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 79 Hungarian (ARTISJUS) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 80 Danish (KODA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 81 Netherlands (BUMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 83 Finnish (TEOSTO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 84 French (SACEM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 85 German (GEMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 86 Hong Kong (CASH) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 87 Italian (SIAE) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 88 Mexican (SACM) General & Broadcasting -

Three the Hard Way Wilfred Limonious: in Fine Style Alex Bartsch: Covers Maxine Walters: Serious Things a Go Happen

HVW8 BERLIN — HVW8 Gallery Berlin in collaboration with One Love Books presents THREE THE HARD WAY WILFRED LIMONIOUS: IN FINE STYLE ALEX BARTSCH: COVERS MAXINE WALTERS: SERIOUS THINGS A GO HAPPEN Cover illustration from the LP Dance Hall Time by Various Artistes (Scar Face Music, 1986) In Fine Style: The Dancehall Art of Wilfred Limonious, is the first solo exhibition of work by prolific Jamaican illustrator Wilfred Limonious (1949–99) in Germany, and includes reproductions of work from the early 1970s through the mid-1990s, spanning three key phases in his career: his comic strips for the Jamaican newspapers, his illustrations for the publications of JAMAL (the Jamaican Movement for the Advancement of Literacy), and his distinctive artwork for the burgeoning dancehall scene coming out of 1980s Jamaica. The exhibition is curated by Al “Fingers” Newman and Christopher Bateman and is produced by One Love Books with the support of the Limonious Estate, to accompany their book, In Fine Style: The Dancehall Art of Wilfred Limonious, the first study into the artist’s life and work. London-based photographer Alex Bartsch makes his debut at HVW8 Gallery Berlin with photographs from his book, Covers: Retracing Reggae Record Sleeves in London, forthcoming on One Love Books. After researching various reggae LPs and twelve-inches from his record collection, Bartsch has re-photographed fifty sleeves in their original London locations, holding them up at arm’s-length so that they blend in with their surroundings, decades later. Presented in this way, the photographs document the transition of time, with the album cover serving as a window into the past, juxtaposed against today’s backdrop. -

United Reggae Magazine #5

MAGAZINE #6 - March 2011 Lady Saw Maikal X Wayne Smith Wayne Wonder Earl 16 Andrew Tosh Richie Spice INTERVIEW London's Passing Clouds Ken Boothe and Big Youth in Paris Jah Mason and Lyricson in France Reggae Month 2011 EME Awards 2011 United Reggae Mag #6 - March 2011 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS 3 - 21 2/ INTERVIEWS • Richie Spice 23 • Maikal X 28 • Lady Saw 34 • Wayne Smith 37 • Andrew Tosh 43 • Earl 16 47 3/ REVIEWS • The Small Axe Guide to Reggae 68-70 51 • Book Of Job by Richie Spice 52 • Tiger Most Wanted 53 • Heat by Little Roy 54 • Sheya Mission - Nine Signs and Heavy Bliss 55 4/ ARTICLES • In The Spotlight: Bizot Bar Opens, RIDDIM speaks, LEGENDary Eats 57 • Wayne Wonder’s Unplanned Hit 60 5/ PHOTOS • Ken Boothe and Big Youth in Paris 63 • Giddeon Family, Natty and Babylon at London’s Passing Clouds 64 • Reggae Month 2011 66 • EME Awards 2011 69 • Jah Mason and Lyricson in France 72 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com. This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/. Not for resale. United Reggae. All Rights Reserved. Any reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited. NEWS News 4 18th Annual 9 Mile Music Festival four cans of food.