Racism, Temporality, Narcissism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

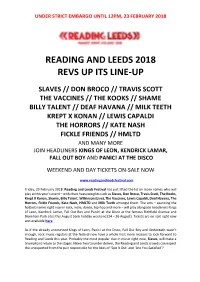

Reading and Leeds 2018 Revs up Its Line-Up

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 READING AND LEEDS 2018 REVS UP ITS LINE-UP SLAVES // DON BROCO // TRAVIS SCOTT THE VACCINES // THE KOOKS // SHAME BILLY TALENT // DEAF HAVANA // MILK TEETH KREPT X KONAN // LEWIS CAPALDI THE HORRORS // KATE NASH FICKLE FRIENDS // HMLTD AND MANY MORE JOIN HEADLINERS KINGS OF LEON, KENDRICK LAMAR, FALL OUT BOY AND PANIC! AT THE DISCO WEEKEND AND DAY TICKETS ON-SALE NOW www.readingandleedsfestival.com Friday, 23 February 2018: Reading and Leeds Festival has just lifted the lid on more names who will play at this year’s event – with chart heavyweights such as Slaves, Don Broco, Travis Scott, The Kooks, Krept X Konan, Shame, Billy Talent, Wilkinson (Live), The Vaccines, Lewis Capaldi, Deaf Havana, The Horrors, Fickle Friends, Kate Nash, HMLTD and Milk Teeth amongst them. The acts – spanning the hottest names right now in rock, indie, dance, hip-hop and more – will play alongside headliners Kings of Leon, Kendrick Lamar, Fall Out Boy and Panic! at the Disco at the famous Richfield Avenue and Bramham Park sites this August bank holiday weekend (24 – 26 August). Tickets are on-sale right now and available here. As if the already announced Kings of Leon, Panic! at the Disco, Fall Out Boy and Underøath wasn’t enough, rock music regulars at the festival now have a whole host more reasons to look forward to Reading and Leeds this year. Probably the most popular duo in music right now, Slaves, will make a triumphant return to the stages. Never two to under deliver, the Reading and Leeds crowds can expect the unexpected from the pair responsible for the likes of ‘Spit It Out’ and ‘Are You Satisfied’? UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 With another top 10 album, ‘Technology’, under their belt, Don Broco will be joining the fray this year. -

Grime + Gentrification

GRIME + GENTRIFICATION In London the streets have a voice, multiple actually, afro beats, drill, Lily Allen, the sounds of the city are just as diverse but unapologetically London as the people who live here, but my sound runs at 140 bpm. When I close my eyes and imagine London I see tower blocks, the concrete isn’t harsh, it’s warm from the sun bouncing off it, almost comforting, council estates are a community, I hear grime, it’s not the prettiest of sounds but when you’ve been raised on it, it’s home. “Grime is not garage Grime is not jungle Grime is not hip-hop and Grime is not ragga. Grime is a mix between all of these with strong, hard hitting lyrics. It's the inner city music scene of London. And is also a lot to do with representing the place you live or have grown up in.” - Olly Thakes, Urban Dictionary Or at least that’s what Urban Dictionary user Olly Thake had to say on the matter back in 2006, and honestly, I couldn’t have put it better myself. Although I personally trust a geezer off of Urban Dictionary more than an out of touch journalist or Good Morning Britain to define what grime is, I understand that Urban Dictionary may not be the most reliable source due to its liberal attitude to users uploading their own definitions with very little screening and that Mr Thake’s definition may also leave you with more questions than answers about what grime actually is and how it came to be. -

Scotland's Creative Writing Centre 2016 Programme

SCOTLAND’S CREATIVE WRITING CENTRE 2016 PROGRAMME WWW.MONIACKMHOR.ORG.UK MONIACK MHOR Something is dealing from a deck of cards, face up, seven, a week of mornings, today’s revealing the hills at Moniack Mhor, shrugging off their mists. A sheepdog barks six fields away; I see the farm from here. Twelve-month cards, each one thumbed, flipped, weathered in its way – this the eighth, harvest-time, a full moon like a trump, a magic trick. It rose last night above this house, affirmative. I sensed your answer – hearts. Or a single hour is a smiling Jack, a diamond, or a spade learning a grave; charms or dark lessons. Something is shuffling; the soft breath of Moniack Mhor on the edge of utterance, I know it, the verbs of swifts riffling the air and the road turning itself into the loch, a huge ace into which everything folds. Here is the evening, displayed then dropped to drift to the blazon of barley, bracken, heather. Something is gifting this great gold gathering of cloud; a continual farewell. CAROL ANN DUFFY WELCOME Dear all, Welcome to Moniack Mhor Creative Writing Centre, based in the beautiful highlands of Scotland. Perched at 1000ft, just a stone’s throw from Loch Ness, the centre commands dramatic views of the mountain ranges of Ben Wyvis and Glen Strathfarrar. Our cosy converted croft is an inspiring atmosphere for doing what we love best, writing. 2015 was a thrilling and creative year in the life of the newly fledged, independent Moniack Mhor. We’ve been visited by many writers from all walks of life, each sharing a different story, breathing energy into the walls of the building. -

4 November 2011 Page 1 of 17

Radio 4 Listings for 29 October – 4 November 2011 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 29 OCTOBER 2011 SAT 06:30 Farming Today (b016k6xb) 60 years ago the vision of a united Europe burned brightly as an Farming Today This Week inspiration to keep the peace after two world wars. But attitudes SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b016869m) have changed since then, and a new generation of Euro sceptics The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. Plans to expand two National Parks in England have re-ignited has emerged. Followed by Weather. the debate over whether the authorities that control the parks Lord Hannay former European Diplomat, Ben Page of the are striking the right balance between preservation and polling organisation Ipsos Mori, and George Eustice de facto modernisation. The proposals being considered by the Secretary leader of the new wave of Conservative Euroscpetic MPs SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b016g4wr) of State, would see the boundaries stretch around the Lake discuss the background to these changes. State of the Union District and Yorkshire Dales parks. There has been a mixed response from the people who could soon be living and working While Europe twists and turns over bailouts the Scottish Episode 5 under the jurisdiction of a Park Authority for the first time. Caz Nationalist party is working towards independence. But why are Graham visits one village, Orton in East Cumbria where some they not calling a referendum now? Stewart Hosie of the SNP Five prominent thinkers from five EU countries offer personal are delighted with the possibility of more tourism whilst others talks to Labour MP Tom Harris -a candidate for the Scottish reflections on the idea of Europe at this critical moment in its are concerned about restrictions on planning and development. -

Jihad.De Jihadistische Online-Propaganda: Empfehlungen Für Gegenmaßnahmen in Deutschland

SWP-Studie Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik Deutsches Institut für Internationale Politik und Sicherheit Asiem El Difraoui jihad.de Jihadistische Online-Propaganda: Empfehlungen für Gegenmaßnahmen in Deutschland S 5 Februar 2012 Berlin Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Abdruck oder vergleichbare Verwendung von Arbeiten der Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik ist auch in Aus- zügen nur mit vorheriger schriftlicher Genehmigung gestattet. SWP-Studien unterliegen einem Begutachtungsverfah- ren durch Fachkolleginnen und -kollegen und durch die Institutsleitung (peer review). Sie geben ausschließlich die persönliche Auffassung der Autoren und Autorinnen wieder. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2012 SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik Deutsches Institut für Internationale Politik und Sicherheit Ludwigkirchplatz 34 10719 Berlin Telefon +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1611-6372 Eine Studie im Rahmen des von der Gerda-Henkel-Stiftung geförderten Projekts »Jihadismus im Internet: Die Internationalisierung von Gewaltdiskursen im World Wide Web« Inhalt 5 Problemstellung und Empfehlungen 7 Vorbemerkung: Islamismus, Salafismus und Jihadismus 10 Entwicklung, Struktur und Inhalte des jihadistischen Internet 10 Vom Hindukusch nach Neukölln – die Geschichte 10 Phase 1: Die Vorgeschichte des Online-Jihad am Hindukusch (1979–1989) 11 Phase 2: Londonistan – Jihadismus im Herzen Europas (1990–2001) 11 Phase 3: Die Globalisierung des Cyberjihad (2001–2006) 13 Phase 4: Web 2.0 – Facebook- und YouTube-Jihad (seit 2006) -

Language and Ethnic Identity in a Multi-Ethnc High School in Wales

LANGUAGE AND ETHNIC IDENTITY IN A MULTI- ETHNC HIGH SCHOOL IN WALES A case study A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social Sciences Cardiff University Author: Hayat Graoui July 2019 Acknowledgements All praise be to Allah whose providence blessed my steps throughout this research project from start to finish, and peace and blessings be upon Mohammed, his last messenger. Words have very often failed me throughout the process of writing this thesis, but they seem even harder to find when trying to acknowledge the kind contribution of people whose support shored up my research journey and helped to bring this project to light. Thank you mum and dad! Every letter and breath in this work was graced with the belief you always had in me. You both are hardly able to read or write, but knew very well how to teach me the value of education and the power of words. Mum, I’m sorry I could only cry and pray when your disease came by, I love you and miss you every day, and I’m so sorry we never had a proper goodbye when I left that day. May you live longer dad, even if all you could recall of now me is taking me to school holding my hand. I wish you could understand that I am doing well and hope that I have made you both proud. I am deeply grateful to my supervisors, Dr Raya Jones and Dr Dawn Mannay, for helping me identify my skills and for consistently increasing my potential to grasp difficult ideas. -

Countering Violent Extremism Scientific Methods & Strategies

TOPICAL STRATEGIC MULTI-LAYER ASSESSMENT AND AIR FORCE RESEARCH LABORATORY MULTI-DISCIPLINARY WHITE PAPER IN SUPPORT OF COUNTER-TERRORISM AND COUNTER-WMD Countering Violent Extremism Scientific Methods & Strategies Revised & Updated1 July 2015 The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the organizations with which they are associated. Editor: Laurie Fenstermacher (Air Force Research Laboratory) Contributing Authors: Lt. Gen John N. “Jack” Shanahan, Ziad Alahdad, Latéfa Belarouci, Cheryl Benard, Kurt Braddock, William Casebeer, Steve Corman, Paul Davis, Karl DeRouen, Diane DiEuliis, Evelyn Early, Alexis Everington, Dipak Gupta, Tawfik Hamid, John Horgan, Qamar-ul Huda, Eric Larson, Anthony Lemieux, Robert Nill, Paulina Pospieszna, Tom Rieger, Marc Sageman, Anne Speckhard, Troy Thomas, Lorenzo Vidino Integration Editors: Sarah Canna & George Popp NSI, Inc. [email protected] 1 Originally Published September 2011 1 NOTE FROM THE EDITOR Why are we reissuing the paper collection, “Countering Violent Extremism: Scientific Methods and Strategies”? The answer is simple. Five years later, violent extremism is still an issue. In September 2014, President Obama spoke at the United Nations, calling on member nations to do more to address violent extremism. This was followed by a three-day summit in February 2015 to bring together local, federal, and international leaders to discuss approaches to counter violent extremism. The wisdom contained in this paper collection is more relevant than ever. I encourage everyone to read it, again or for the first time, in whole or in part. 2 CONTENTS Foreword (Lt. Gen. John N. “Jack” Shanahan) ............................................................................................................... 1 Preface (Diane DiEuiliis) ............................................................................................................................................... -

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List Australia FOX Sport 502 FOX LEAGUE HD Australia FOX Sport 504 FOX FOOTY HD Australia 10 Bold Australia SBS HD Australia SBS Viceland Australia 7 HD Australia 7 TV Australia 7 TWO Australia 7 Flix Australia 7 MATE Australia NITV HD Australia 9 HD Australia TEN HD Australia 9Gem HD Australia 9Go HD Australia 9Life HD Australia Racing TV Australia Sky Racing 1 Australia Sky Racing 2 Australia Fetch TV Australia Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Rugby League 1 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 2 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 3 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 1HD Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 2HD Australia -

Phil Sumpter Dir

Contact: Phil Sumpter Dir. of Marketing & Communications 215.925.9914 ext. 15 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 16, 2011 UK’S SOWETO KINCH TOURS US/DEBUTS PHILLY WITH LATEST BEBOP- HIP-HOP HYBRID; SHOW SERVES AS BRIDE’S SEASON FINALE Philadelphia, PA – Painted Bride Art Center presents award-winning British-based saxophonist and MC Soweto Kinch and his latest bebop/ hip-hop hybrid release The New Emancipation. Soweto leads his quartet to the Bride’s stage to perform on Saturday, June 11 at 8pm serving as the venue’s 2011 season finale. WRTI’s J. Michael Harrison, host to the cutting- edge jazz program The Bridge, joins the Bride’s for this special presentation. “Soweto Kinch raps like a champion and plays like a dream.” – London Evening Standard Birmingham-raised, Oxford-educated saxophonist and rapper Soweto Kinch is considered the most exciting and versatile young musicians in both the British jazz and hip hop scenes. This is because of his bar none ability to weave together such diverse influences as Charlie Parker, Madlib, Ornette Coleman, Stevie Wonder and Duke Ellington with high energy and polished style. His impressive list of accolades and awards includes a Mercury Music Prize nomination, two UMA Awards, and two MOBO Awards for best Jazz Act. At the O2 Arena, London he was announced as the winner in the Best Jazz Act category- fending off stiff competition from the likes of Wynton Marsalis. His skills as a hip hop MC and producer are highly respected by the likes of KRS ONE, Dwele and TY, and he is being championed by the likes of Mos Def, Rodney P and BBC 1-Xtra’s Twin B. -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson, -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 131 “New Silk Road: Business Cooperation and Prospective of Economic Development” (NSRBCPED 2019) The Analysis of UK and US Migration Policies in Relation to the Middle East Countries Aleksander Eremin Irina Kuprieva The faculty of intercultural communications and The faculty of Linguistics international relations A.S. Griboedov Institute of International Law and Belgorod National Research University Economics Belgorod, Russia The School of Education [email protected] Far Eastern Federal University Moscow, Russia [email protected] Abstract— Of course, the influx of migrants to the countries unskilled ones) to which is so great that it begins to threaten mentioned above comes not only from the Middle East and not not only cultural identity, but also the safety of people who only to the UK and the US, but as part of this study, we are originally lived in these territories due to the emerging social interested particularly in the problem of the interaction of the tension. Arabic-speaking and English-speaking peoples. The article analyzes the current situation in the field of In the article, we will try to analyze this problem using the migration policy in the United States and Great Britain, as well example of the United States of America and Great Britain as as the circumstances that led to this. Analysis data may be used continental leaders in terms of the number of incoming to better understand the situation of immigrants from Arab migrants, and consider their situation with migrants from the countries to countries where the official language is English. -

INDIAN OTT PLATFORMS REPORT 2019 New Regional Flavours, More Entertaining Content

INDIAN OTT PLATFORMS REPORT 2019 New Regional Flavours, more Entertaining Content INDIAN TRENDS 2018-19 Relevant Statistics & Insights from an Indian Perspective. Prologue Digital technology has steered the third industrial revolution and influenced human civilization as a whole. A number of industries such as Media, Telecom, Retail and Technology have witnessed unprecedented disruptions and continue to evolve their existing infrastructure to meet the challenge. The telecom explosion in India has percolated to every corner of the country resulting in easy access to data, with Over-The-Top (OTT) media services changing how people watch television. The Digital Media revolution has globalized the world with 50% of the world’s population going online and around two-thirds possessing a mobile phone. Social media has penetrated into our day-to-day life with nearly three billion people accessing it in some form. India has the world’s second highest number of internet users after China and is fully digitally connected with the world. There is a constant engagement and formation of like-minded digital communities. Limited and focused content is the key for engaging with the audience, thereby tapping into the opportunities present, leading to volumes of content creation and bigger budgets. MICA, The School of Ideas, is a premier Management Institute that integrates Marketing, Branding, Design, Digital, Innovation and Creative Communication. MICA offers specializations in Digital Communication Management as well as Media & Entertainment Management as a part of its Two Year Post Graduate Diploma in Management. In addition to this, MICA offers an online Post-Graduate Certificate Programme in Digital Marketing and Communication.