Grime + Gentrification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nick Cage Direction

craft production just because of what it does with sampling technology and that alone. It’s got quite a conservative form and quite a pop form as well just at the moment, in terms of the clarity of the sonics. When those elements are added to hip-hop tracks it must be difficult to make the vocal stand out. The biggest challenge is always getting the vocal heard on top of the track — the curse of the underground is an ill-defined vocal. When I went to bigger studios and used 1176s and LA2s it was a revelation, chucking one of them on gets the vocal up a bit. That’s how we were able to blag our way through Dizzee’s first album. What do you use in Dizzee’s vocal chain? With the budget we were on when I did Boy In Da Corner I used a Neumann TLM103B. When I bought it, £500 seemed a hell of a lot of money for a microphone. Then it goes to my Drawmer 1960 — I exchanged a couple of my keyboards for that. Certainly with Showtime, the new desk improved the vocal sound. It would be interesting to just step the gear up a notch, now we have the deal with XL, and see what happens. Do you have a label deal for Dirty Stank records with XL? I Love You came out first on Dirty Stank on the underground, plus other tunes like Ho and some beats. XL has licensed the albums from Dirty Stank so it’s not a true label deal in that sense, although with our first signings, it’s starting to move in that Nick Cage direction. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Risktaking Behavior in Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

FULL-LENGTH ORIGINAL RESEARCH Risk-taking behavior in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy *†Britta Wandschneider, *†Maria Centeno, *†‡Christian Vollmar, *†Jason Stretton, §Jonathan O’Muircheartaigh, *†Pamela J. Thompson, ¶Veena Kumari, *†Mark Symms, §Gareth J. Barker, *†John S. Duncan, #Mark P. Richardson, and *†Matthias J. Koepp Epilepsia, 0(0):1–8, 2013 doi: 10.1111/epi.12413 SUMMARY Objective: Patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) often present with risk-tak- ing behavior, suggestive of frontal lobe dysfunction. Recent studies confirm functional and microstructural changes within the frontal lobes in JME. This study aimed at char- acterizing decision-making behavior in JME and its neuronal correlates using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Methods: We investigated impulsivity in 21 JME patients and 11 controls using the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT), which measures decision making under ambiguity. Perfor- mance on the IGT was correlated with activation patterns during an fMRI working memory task. Results: Both patients and controls learned throughout the task. Post hoc analysis revealed a greater proportion of patients with seizures than seizure-free patients hav- ing difficulties in advantageous decision making, but no difference in performance between seizure-free patients and controls. Functional imaging of working memory networks showed that overall poor IGT performance was associated with an increased Dr. Wandschneider is activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in JME patients. Impaired registrar in neurology learning during the task and ongoing seizures were associated with bilateral medial and is pursuing a PhD prefrontal cortex (PFC) and presupplementary motor area, right superior frontal at the UCL Institute of gyrus, and left DLPFC activation. Neurology. -

Ebook Download This Is Grime Ebook, Epub

THIS IS GRIME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hattie Collins | 320 pages | 04 Apr 2017 | HODDER & STOUGHTON | 9781473639270 | English | London, United Kingdom This Is Grime PDF Book The grime scene has been rapidly expanding over the last couple of years having emerged in the early s in London, with current grime artists racking up millions of views for their quick-witted and contentious tracks online and filling out shows across the country. Sign up to our weekly e- newsletter Email address Sign up. The "Daily" is a reference to the fact that the outlet originally intended to release grime related content every single day. Norway adjusts Covid vaccine advice for doctors after admitting they 'cannot rule out' side effects from the Most Popular. The awkward case of 'his or her'. Definition of grime. This site uses cookies. It's all fun and games until someone beats your h Views Read Edit View history. During the hearing, David Purnell, defending, described Mondo as a talented musician and sportsman who had been capped 10 times representing his country in six-a-side football. Fernie, aka Golden Mirror Fortunes, is a gay Latinx Catholic brujx witch — a combo that is sure to resonate…. Scalise calls for House to hail Capitol Police officers. Drill music, with its slower trap beats, is having a moment. Accessed 16 Jan. This Is Grime. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. More On: penn station. Police are scrambling to recover , pieces of information which were WIPED from records in blunder An unwillingness to be chained to mass-produced labels and an unwavering honesty mean that grime is starting a new movement of backlash to the oppressive systems of contemporary society through home-made beats and backing tracks and enraged lyrics. -

Slang in American and British Hip-Hop/Rap Song Lyrics

LEXICON Volume 5, Number 1, April 2018, 84-94 Slang in American and British Hip-Hop/Rap Song Lyrics Tessa Zelyana Hidayat*, Rio Rini Diah Moehkardi Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia *Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This research examines semantic changes and also the associative patterns of slang, focusing primarily on common topics, i.e., people and drugs. The data were slang terms taken from the lyrics of hip-hop/rap songs sung by four singers, two from the U.S.A and two from the U.K. A total of 105 slang terms were found, 45 of which belong to the people category and 16 to the drugs category in the American hip-hop/rap song lyrics, and in the British hip-hop/rap song lyrics, 26 of which belong to the people category and 18 to the drugs category. Bitch and nigga were found to be the most frequently used slang terms in the people category. In terms of semantic changes, broadening, amelioration, and narrowing were found, and in terms of associative patterns, effect, appearance, way of consuming, constituent, and container associative patterns were found. In addition, a new associative pattern was found, i.e., place of origin. Keywords: associative patterns, people and drugs slang, semantic change, slang. mislead people outside their group. Then, the INTRODUCTION usage of Cant began to slowly develop. Larger “This party is just unreal!” Imagine a person groups started to talk Cant in their daily life. It saying this sentence in the biggest New Year’s Eve was even used for entertainment purposes, such as party in his/her town, with the largest crowd, the in literature. -

Liste CD / Vinyle Collection En Vente Reggae Ragga Dancehall… 2 Achetés = 1 Offert Lot Possible Et Négociable Contactez Hip Hop Music Museum

1 Liste CD / Vinyle Collection en vente Reggae Ragga dancehall… 2 achetés = 1 offert Lot possible et négociable Contactez hip hop music museum Type Prix Nom de l’artiste Nom de l’album de Genre Année Etat Qté média 100% Ragga Dj Ewone CD 2005 1 5 Reggaetton Admiral T Touchez l’horizon Vinyl Dancehall 2006 1 9,50 Admiral T Instinct admiral CD Dancehall 2010 1 6,99 Digipack Alpha Blondy Revolution CD Reggae 1987 0 2,90 Alpha Blondy Masada CD Reggae 1992 1 25 Alpha Blondy Yitzhak rabin CD Reggae 2010 1 25 Alpha Blondy Vision CD Reggae 2011 1 6,99 And why not Move your skin CD Reggae 1990 1 3,99 Anthony B Universal struggle CD Reggae 1997 1 6,99 ASWAD Not Satisfied CD Reggae 1994 0 9,90 Baaba maal Yela CD Single Reggae 1993 1 29,99 promo Bad manners Inner London violence CD Reggae 1994 1 20,99 Baobab Reggae social club CD Reggae 2001 1 9,99 Beyond the front line Various CD Reggae 1990 1 2,55 Big Red RED emption /respect or die CD Single Reggae 1999 1 6,99 Big Red Big Redemption CD Ragga 1999 3 1,98 2 Big RED REDsistance CD Reggae 2001 1 2,40 Black Uhuru RED CD Reggae 1981 1 1,80 Bob Marley Natty Dread Vinyl Reggae 1974 0 18 Bob Marley Survival CD Reggae 1979 1 10 Bob Marley Saga CD Reggae 1990 1 4,40 Bob Marley Iron lion zion Reggae 1992 1 1,99 Bob Marley Dont rock my boat CD Reggae 1993 1 4,50 Bob Marley Talkin blues CD Reggae 1995 1 10 BoB Marley Keep on moving CD Reggae 1996 1 6 Bob Marley Bob MARLEY CD Reggae 1997 1 8,20 Bob Marley Chant down Babylon CD Reggae 1999 1 3 Bob Marley One love best of CD Reggae 2001 1 10 Bob Marley Thank you -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

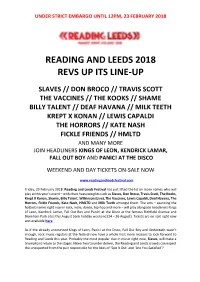

Reading and Leeds 2018 Revs up Its Line-Up

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 READING AND LEEDS 2018 REVS UP ITS LINE-UP SLAVES // DON BROCO // TRAVIS SCOTT THE VACCINES // THE KOOKS // SHAME BILLY TALENT // DEAF HAVANA // MILK TEETH KREPT X KONAN // LEWIS CAPALDI THE HORRORS // KATE NASH FICKLE FRIENDS // HMLTD AND MANY MORE JOIN HEADLINERS KINGS OF LEON, KENDRICK LAMAR, FALL OUT BOY AND PANIC! AT THE DISCO WEEKEND AND DAY TICKETS ON-SALE NOW www.readingandleedsfestival.com Friday, 23 February 2018: Reading and Leeds Festival has just lifted the lid on more names who will play at this year’s event – with chart heavyweights such as Slaves, Don Broco, Travis Scott, The Kooks, Krept X Konan, Shame, Billy Talent, Wilkinson (Live), The Vaccines, Lewis Capaldi, Deaf Havana, The Horrors, Fickle Friends, Kate Nash, HMLTD and Milk Teeth amongst them. The acts – spanning the hottest names right now in rock, indie, dance, hip-hop and more – will play alongside headliners Kings of Leon, Kendrick Lamar, Fall Out Boy and Panic! at the Disco at the famous Richfield Avenue and Bramham Park sites this August bank holiday weekend (24 – 26 August). Tickets are on-sale right now and available here. As if the already announced Kings of Leon, Panic! at the Disco, Fall Out Boy and Underøath wasn’t enough, rock music regulars at the festival now have a whole host more reasons to look forward to Reading and Leeds this year. Probably the most popular duo in music right now, Slaves, will make a triumphant return to the stages. Never two to under deliver, the Reading and Leeds crowds can expect the unexpected from the pair responsible for the likes of ‘Spit It Out’ and ‘Are You Satisfied’? UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 With another top 10 album, ‘Technology’, under their belt, Don Broco will be joining the fray this year. -

With Alcohol

Faculty of Health Sciences National Drug Research Institute An ethnographic study of recreational drug use and identity management among a network of electronic dance music enthusiasts in Perth, Western Australia Rachael Renee Green This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University September 2012 i Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: …………………………………………. Date: ………………………... ii Abstract This thesis explores the social contexts and cultural significance of amphetamine- type stimulant (ATS) and alcohol use among a social network of young adults in Perth, Western Australia. The study is positioned by the “normalisation thesis” (Parker et al . 1998), a body of scholarly work proposing that certain “sensible” forms of illicit drug use have become more culturally acceptable or normal among young people in the United Kingdom (UK) population since the 1990s. Academic discussion about cultural processes of normalisation is relevant in the Australian context, where the prevalence of illicit drug use among young adults is comparable to the UK. This thesis develops the work of Sharon Rødner Sznitman (Rødner, 2005, 2006; Rødner Sznitman, 2008), who argued that normalisation researchers have neglected the “micro-politics that drug users might be engaged in when trying to challenge the stigma attached to them” (Rødner Sznitman, 2008, pp.456-457). Ethnographic fieldwork was conducted among ‘scenesters’ – members of a social network that was based primarily on involvement in Perth’s electronic dance music (EDM) ‘scene’. -

Connotative Meanings in Ed Sheeran's Song Lyrics

CONNOTATIVE MEANINGS IN ED SHEERAN’S SONG LYRICS THESIS Submitted as a Partial Requirements for the degree of Sarjana in English Letters Department Written By: WAHYU KUSUMANINGRUM SRN. 163 211 050 ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT CULTURES AND LANGUAGES FACULTY THE STATE ISLAMIC INSTITUTE OF SURAKARTA 2020 CONNOTATIVE MEANINGS IN ED SHEERAN’S SONG LYRICS THESIS Submitted as a Partial Requirements for the degree of Sarjana in English Letters Department Written By: WAHYU KUSUMANINGRUM SRN. 163 211 050 ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT CULTURES AND LANGUAGES FACULTY THE STATE ISLAMIC INSTITUTE OF SURAKARTA 2020 i ADVISOR SHEET Subject : Thesis of Wahyu Kusumaningrum SRN : 163211050 To: The Dean of Cultures and Languages Faculty IAIN Surakarta In Surakarta \ Assalamu’alaikum Wr. Wb. After reading thoroughly and giving necessary advices, herewith, as the advisors, we state that the thesis of Name : Wahyu Kusumaningrum SRN : 16.32.1.1.050 Title : Connotative Meanings in Ed Sheeran’s Song Lyrics has already fulfilled the requirements to be presented before the board of Examiners (munaqosyah) to gain Bachelor Degree in English Letters. Thank you for the attention Wassalamu’alaikum Wr. Wb. Surakarta, November 2, 2020 Advisor Robith Khoiril Umam S.S., M.Hum. NIP. 19871011 201503 1 006 ii iii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to: 1. Myself 2. My beloved parents 3. My beloved family 4. English Letters 2016 5. English Letters Department 6. My Almamater IAIN Surakarta iv MOTTO “Dan (ingatlah juga), tatkala Tuhanmu memaklumkan; "Sesungguhnya jika kamu bersyukur, pasti Kami akan menambah (nikmat) kepadamu, dan jika kamu mengingkari (nikmat-Ku), maka sesungguhnya azab-Ku sangat pedih.” (Q.S. -

The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 122–135 Research Article Adam de Paor-Evans* The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0012 Received January 27, 2018; accepted June 2, 2018 Abstract: In the early 1980s, an important facet of hip hop culture developed a style of music known as electro-rap, much of which carries narratives linked to science fiction, fantasy and references to arcade games and comic books. The aim of this article is to build a critical inquiry into the cultural and socio- political presence of these ideas as drivers for the productions of electro-rap, and subsequently through artists from Newcleus to Strange U seeks to interrogate the value of science fiction from the 1980s to the 2000s, evaluating the validity of science fiction’s place in the future of hip hop. Theoretically underpinned by the emerging theories associated with Afrofuturism and Paul Virilio’s dromosphere and picnolepsy concepts, the article reconsiders time and spatial context as a palimpsest whereby the saturation of digitalisation becomes both accelerator and obstacle and proposes a thirdspace-dromology. In conclusion, the article repositions contemporary hip hop and unearths the realities of science fiction and closes by offering specific directions for both the future within and the future of hip hop culture and its potential impact on future society. Keywords: dromosphere, dromology, Afrofuturism, electro-rap, thirdspace, fantasy, Newcleus, Strange U Introduction During the mid-1970s, the language of New York City’s pioneering hip hop practitioners brought them fame amongst their peers, yet the methods of its musical production brought heavy criticism from established musicians. -

Dancehall Dossier.Cdr

DANCEHALL DOSSIER STOP M URDER MUSIC DANCEHALL DOSSIER Beenie Man Beenie Man - Han Up Deh Hang chi chi gal wid a long piece of rope Hang lesbians with a long piece of rope Beenie Man Damn I'm dreaming of a new Jamaica, come to execute all the gays I'm dreaming of a new Jamaica, come to execute all the gays Beenie Man Beenie Man - Batty Man Fi Dead Real Name: Anthony M Davis (aka ‘Weh U No Fi Do’) Date of Birth: 22 August 1973 (Queers Must Be killed) All batty man fi dead! Jamaican dancehall-reggae star Beenie All faggots must be killed! Man has personally denied he had ever From you fuck batty den a coppa and lead apologised for his “kill gays” music and, to If you fuck arse, then you get copper and lead [bullets] prove it, performed songs inciting the murder of lesbian and gay people. Nuh man nuh fi have a another man in a him bed. No man must have another man in his bed In two separate articles, The Jamaica Observer newspaper revealed Beenie Man's disavowal of his apology at the Red Beenie Man - Roll Deep Stripe Summer Sizzle concert at James Roll deep motherfucka, kill pussy-sucker Bond Beach, Jamaica, on Sunday 22 August 2004. Roll deep motherfucker, kill pussy-sucker Pussy-sucker:a lesbian, or anyone who performs cunnilingus. “Beenie Man, who was celebrating his Tek a Bazooka and kill batty-fucker birthday, took time to point out that he did not apologise for his gay-bashing lyrics, Take a bazooka and kill bum-fuckers [gay men] and went on to perform some of his anti- gay tunes before delving into his popular hits,” wrote the Jamaica Observer QUICK FACTS “He delivered an explosive set during which he performed some of the singles that have drawn the ire of the international Virgin Records issued an apology on behalf Beenie Man but within gay community,” said the Observer.