Subcultural Identities in British Reggae Lyrics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

The Arts of Resistance in the Poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson1

Revista África e Africanidades - Ano 3 - n. 11, novembro, 2010 - ISSN 1983-2354 www.africaeafricanidades.com The arts of resistance in the poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson1 Jair Luiz França Junior2 Resumo: Este artigo analisa insubordinação e resistência manifestas na poesia pós-colonial contemporânea como forma de subverter os discursos dominantes no ocidente. Mais especificamente, a análise centra-se em estratégias textuais de resistência no trabalho do poeta britânico-jamaicano Linton Kwesi Johnson (também conhecido como LKJ). A qualidade sincretista na obra desse poeta relaciona-se com diáspora, hibridismo e crioulização como formas de re[escre]ver discursos hegemônicos com bases (neo)coloniais. Críticas pós- coloniais, em geral, irão enquadrar esta análise de estratégias de dominação e resistência, mas algumas discussões a partir do domínio de história, sociologia e estudos culturais também poderão entrar no debate. Neste sentido, há uma grande variedade de teorias e argumentos que lidam com as contradições e incongruências na questão das relações de poder interligada à dominação e resistência. Para uma visão geral do debate, este estudo compõe uma tarefa tríplice. Primeiramente, proponho-me a fazer um breve resumo autobiográfico do poeta e as preocupações sócio-políticas em sua obra. Em seguida, apresento algumas leituras críticas de seus poemas a fim de embasar teorias que lidam com estratégias de dominação e resistência no âmbito da literatura. Por fim, investigo como estratégias de resistência diaspórica e hibridismo cultural empregados na poesia de Linton Kwesi Johnson podem contribuir para o distanciamento das limitações de dicotomias e também subverter o poder hegemônico. Além disso, este debate está preocupado com a crescente importância de estudos acadêmicos voltado às literaturas pós-coloniais. -

Media and Advertising Information Why Advertise on Bigup Radio? Ranked in the Top 50,000 of All Sites According to Amazon’S Alexa Service

Media and Advertising Information Why Advertise on BigUp Radio? Ranked in the top 50,000 of all sites according to Amazon’s Alexa service Audience 16-34 year-old trend-setters and early adopters of new products. Our visitors purchase an average of $40–$50 each time they buy music on bigupradio.com and more than 30% of those consumers are repeat customers. Typical Traffic More than 1,000,000 unique page views per month Audience & Traffic 1.5 million tune-ins to the BigUp Radio stations Site Quick Facts Over 75,000 pod-cast downloads each month of BigUp Radio shows Our Stations Exclusive DJ Shows A Strong Image in the Industry Our Media Player BigUp Radio is in touch with the biggest artists on the scene as well as the Advertising Opportunities hottest upcoming new artists. Our A/R Dept listens to every CD that comes in selecting the very best tracks for airplay on our 7 stations. Among artists that Supporting Artists’ Rights have been on BigUp Radio for interviews and special guest appearances are: Rate Card Beenie Man Tanya Stephens Anthony B Contact Information: Lil Jon I Wayne TOK Kyle Russell Buju Banton Gyptian Luciano (617) 771.5119 Bushman Collie Buddz Tami Chynn [email protected] Cutty Ranks Mr. Vegas Delly Ranx Damian Marley Kevin Lyttle Gentleman Richie Spice Yami Bolo Sasha Da’Ville Twinkle Brothers Matisyahu Ziggi Freddie McGregor Jr. Reid Worldwide Reggae Music Available to anyone with an Internet connection. 7 Reggae Internet Radio Stations Dancehall, Roots, Dub, Ska, Lovers Rock, Soca and Reggaeton. -

The Arts of Resistance in the Poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson

THE ARTS OF RESISTANCE IN THE POETRY OF LINTON KWESI JOHNSON AS ARTES DA RESISTÊNCIA NA POESIA DE LINTON KWESI JOHNSON JLFrança Junior* Resumo Este artigo analisa insubordinação e resistência manifestas na poesia pós-colonial contemporânea como forma de subverter os discursos dominantes no ocidente. Mais especificamente, a análise centra-se em estratégias textuais de resistência no trabalho do poeta britânico-jamaicano Linton Kwesi Johnson. A qualidade sincretista em sua obra relaciona-se com diáspora, hibridismo e crioulização como formas de re[escre]ver discursos hegemônicos com bases (neo)coloniais. Críticas pós-coloniais, em geral, irão enquadrar esta análise. Este estudo está organizado em três debates fundamentais: um breve relato biográfico do autor e a contextualização sociopolítica em que sua obra se insere, alguns exames críticos da poesia de LKJ e um estudo das estratégias de resistência diaspórica e hibridismo cultural empregados na sua poesia. Este artigo visa, portanto, a fazer uma análise literária de poemas pós-coloniais como técnicas estratégicas de descentramento da retórica ocidental dominante, a qual tenta naturalizar desigualdades e injustiças em ambos os contextos local e global. Palavras-chave: Poesia Contemporânea, Crítica Pós-colonial, Diáspora, Crioulização, Resistência. Abstract This paper analyses insubordination and resistance manifested in contemporary postcolonial poetry as ways of subverting dominant Western discourses. More specifically, I focus my analysis on textual strategies of resistance in the works of the British-Jamaican poet Linton Kwesi Johnson. The syncretistic quality in his oeuvre is related to diaspora, hybridity and creolisation as forms of writ[h]ing against (neo)colonially-based hegemonic discourses. Thus postcolonial critiques at large will frame this analysis. -

Linton Kwesi Johnson: Poetry Down a Reggae Wire

LINTON KWESI JOHNSON: POETRY DOWN A REGGAE WIRE by Robert J. Stewart for "Poetry, Motion, and Praxis: Caribbean Writers" panel XVllth Annual Conference CARIBBEAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION St. George's, Grenada 26-29 May, 1992 LINTON KWESI JOHNSON: POETRY DOWN fl RE66flE WIRE Linton Kwesi Johnson had been writing seriously for about four years when his first published poem appeared in 1973. There had been nothing particularly propitious in his experience up to then to indicate that within a relatively short period of time he would become an internationally recognized writer and performer. Now, at thirty-nine years of age, he has published four books of poetry, has recorded seven collections of his poems set to music, and has appeared in public readings and performances of his work in at least twenty-one countries outside of England. He has also pursued a parallel career as a political activist and journalist. Johnson was born in Chapelton in the parish of Clarendon on the island of Jamaica in August 1952. His parents had moved down from the mountains to try for a financially better life in the town. They moved to Kingston when Johnson was about seven years old, leaving him with his grandmother at Sandy River, at the foot of the Bull Head Mountains. He was moved from Chapelton All-Age School to Staceyville All-Age, near Sandy River. His mother soon left Kingston for England, and in 1963, at the age of eleven, Linton emigrated to join her on Acre Lane in Brixton, South London.1 The images of black and white Britain immediately impressed young Johnson. -

Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-18-2007 Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984 Caree Banton University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Banton, Caree, "Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984" (2007). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 508. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/508 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974 – 1984 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History By Caree Ann-Marie Banton B.A. Grambling State University 2005 B.P.A Grambling State University 2005 May 2007 Acknowledgement I would like to thank all the people that facilitated the completion of this work. -

The Performance of Accents in the Work of Linton Kwesi Johnson and Lemn Sissay

Thamyris/Intersecting No. 14 (2007) 51-68 “Here to Stay”: The Performance of Accents in the Work of Linton Kwesi Johnson and Lemn Sissay Cornelia Gräbner Introduction In his study Accented Cinema, Hamid Naficy uses the term “accent” to designate a new cinematic genre. This genre, which includes diasporic, ethnic and exilic films, is char- acterized by a specific “accented” style. In his analysis of “accented style,” Naficy broad- ens the term “accent” to refer not only to speech but also to “the film’s deep structure: its narrative visual style, characters, subject matter, theme, and plot” (Naficy 23). Thus, the term “accent” describes an audible characteristic of speech but can also be applied to describe many characteristics of artistic products that originate in a par- ticular community. “Accented films” reflect the dislocation of their authors through migration or exile. According to Naficy, the filmmakers operate “in the interstices of cultures and film practices” (4). Thus, Naficy argues, “accented films are interstitial because they are created astride and in the interstices of social formations and cinematic practices” (4). Naficy’s use of the term interstice refers back to Homi Bhabha, who argues that cultural change originates in the interstices between different cultures. Interstices are the result of “the overlap and displacement of domains of difference” (Bhabha 2). In the interstice, “social differences are not simply given to experience through an already authenticated cultural tradition” (3). Thus, the development of alternative styles and models of cultures, and the questioning of the cultures that dominate the space outside the interstice is encouraged. -

Jah Free 2016

JAH FREE 2016 THE DUB ACTIVIST The unique sounds of JAH FREE MUSIC seems to have no boundaries, he really can’t contain or control the movement of his music or where it will take him next. The people really do have the power and it is their love, vibes and support which keeps Jah Free Music very much alive and well today. The man himself never having had a plan, tries to take a natural musical path of progression, following the vibes and trying to always stand for the positive, his most important aim is to bring a ‘one love’ message in his musical works and live shows for anyone who cares to listen. Jah Free has been involved in the UK, European and now global reggae music scene for some 35 years with Roots, Dub, Digital productions and remixes. He first started out playing keys, percussion and singing in his band Tallowah back in the late to early 70s/80s, the band was formed by himself and his musically talented friends. The band’s name was later to become “Bushfire”, remembered by most as a highly successful UK Roots band for its time. Even now people mention those times and the live shows they enjoyed. Bushfire were asked to perform outside of the UK in Europe at festivals notably taking its own Wango Riley Stage on the road with its own mixing desk and P.A included, this being where Jah Free first learnt his many skills in live mixing. Worth mentioning that the Wango Rileys stage went on to become a very well known stage on the festival circuit over its many years, but sadly burnt down in the 90s. -

Ghost Gig: Redskins Programme

13th December 2019 marks slick, The Redskins were Chris Dean was not keen the anniversary of the highly your band’ and lead singer on broader pop and politics politically charged band Chris Dean once claimed allegiances. Discussing Red Redskins playing our New that his ambition was to Wedge, the Labour Party SETLIST Cavendish Street site. The have his band ‘sing like affiliated movement, he noted original concert took place the Supremes and walk that ‘if the Labour Party are in 1985, only a week after like the clash’ (from NWNM organising a tour, the one thing Lean on Me (second single on CNT, 1982)* 6.15 New Order played the same reissue sleevenotes). Their you can be sure about is that Reds strike the blues* 4.34 venue, and were the subject first single Lev Bronstein it’ll sell out’. He in fact talked Hold on!* 3.18 of a ghost gig last year. As (Trotsky’s real name) was about setting up a Redder Unionise (b side of Lean on Me) 4.53 we noted then, 1985 was a released in 1982, followed by Wedge. Certainly they would Kick over the statues! (single, Decca/London 1985)* 2.27 curious and eclectic musical Lean on Me (‘a love song to have not been interested in decade. For Redskins though workers’ solidarity’ said the the Live Aid event that took Ninety nine and a half won’t do (reissue NWNM) 4.20 1985 would have been seen NME) before the band signed place earlier that summer. Take no heroes!* 5.33 as the year of the SDP/ for Decca/London Records. -

What Questions Should Historians Be Asking About UK Popular Music in the 1970S? John Mullen

What questions should historians be asking about UK popular music in the 1970s? John Mullen To cite this version: John Mullen. What questions should historians be asking about UK popular music in the 1970s?. Bernard Cros; Cornelius Crowley; Thierry Labica. Community in the UK 1970-79, Presses universi- taires de Paris Nanterre, 2017, 978-2-84016-287-2. hal-01817312 HAL Id: hal-01817312 https://hal-normandie-univ.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01817312 Submitted on 17 Jun 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. What questions should historians be asking about UK popular music in the 1970s? John Mullen, Université de Rouen Normandie, Equipe ERIAC One of the most important jobs of the historian is to find useful and interesting questions about the past, and the debate about the 1970s has partly been a question of deciding which questions are important. The questions, of course, are not neutral, which is why those numerous commentators for whom the key question is “Did the British people become ungovernable in the 1970s?” might do well to balance this interrogation with other equally non-neutral questions, such as, perhaps, “Did the British elites become unbearable in the 1970s?” My reflection shows, it is true, a preoccupation with “history from below”, but this is the approach most suited to the study of popular music history. -

Copyright by Jessica Lyle Anaipakos 2012

Copyright by Jessica Lyle Anaipakos 2012 The Thesis Committee for Jessica Lyle Anaipakos Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Celebrity and Fandom on Twitter: Examining Electronic Dance Music in the Digital Age APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Shanti Kumar Janet Staiger Celebrity and Fandom on Twitter: Examining Electronic Dance Music in the Digital Age by Jessica Lyle Anaipakos, B.S. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2012 Dedication To G&C and my twin. Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the guidance, encouragement, knowledge, patience, and positive energy of Dr. Shanti Kumar and Dr. Janet Staiger. I am sincerely appreciative that they agreed to take this journey with me. I would also like to give a massive shout out to the Radio-Television-Film Department. A big thanks to my friends Branden Whitehurst and Elvis Vereançe Burrows and another thank you to Bob Dixon from Seven Artist Management for allowing me to use Harper Smith’s photograph of Skrillex from Electric Daisy Carnival. v Abstract Celebrity and Fandom on Twitter: Examining Electronic Dance Music in the Digital Age Jessica Lyle Anaipakos, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2012 Supervisor: Shanti Kumar This thesis looks at electronic dance music (EDM) celebrity and fandom through the eyes of four producers on Twitter. Twitter was initially designed as a conversation platform, loosely based on the idea of instant-messaging but emerged in its current form as a micro-blog social network in 2009. -

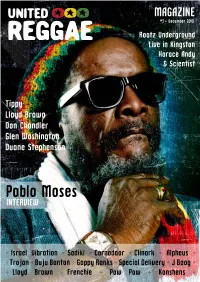

Pablo Moses INTERVIEW

MAGAZINE #3 - December 2010 Rootz Underground Live in Kingston Horace Andy & Scientist Tippy Lloyd Brown Don Chandler Glen Washington Duane Stephenson Pablo Moses INTERVIEW * Israel Vibration * Sadiki * Cornadoor * Clinark * Alpheus * * Trojan * Buju Banton * Gappy Ranks * Special Delivery * J Boog * * Lloyd Brown * Frenchie * Pow Pow * Konshens * United Reggae Mag #3 - December 2010 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month.. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS •Lloyd Brown - Special Delivery - Own Mission Records - Calabash J Boog - Konshens - Trojan - Alpheus - Racer Riddim - Everlasting Riddim London International Ska Festival - Jamaican-roots.com - Buju Banton, Gappy Ranks, Irie Ites, Sadiki, Tiger Records 3 - 9 2/ INTERVIEWS •Interview: Tippy 11 •Interview: Pablo Moses 15 •Interview: Duane Stephenson 19 •Interview: Don Chandler 23 •Interview: Glen Washington 26 3/ REVIEWS •Voodoo Woman by Laurel Aitken 29 •Johnny Osbourne - Reggae Legend 30 •Cornerstone by Lloyd Brown 31 •Clinark - Tribute to Michael Jackson, A Legend and a Warrior •Without Restrictions by Cornadoor 32 •Keith Richards’ sublime Wingless Angels 33 •Reggae Knights by Israel Vibration 35 •Re-Birth by The Tamlins 36 •Jahdan Blakkamoore - Babylon Nightmare 37 4/ ARTICLES •Is reggae dying a slow death? 38 •Reggae Grammy is a Joke 39 •Meet Jah Turban 5/ PHOTOS •Summer Of Rootz 43 •Horace Andy and Scientist in Paris 49 •Red Strip Bold 2010 50 •Half Way Tree Live 52 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com.This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/.