Diplomacy's Value: Creating Security in 1920S Europe and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gamer's Guide, Experimenting with the Intriguing Suggestions All an Relied Will Find Tile Pt:Llalli~ for Mh:Takes Less in One Package

2 ADVANCED CIVILIZATION Preface CIVlLlZA110N is an outstanding game, ADVANCED CNlLlZA1TON" (p.17), which sets which has been played by many who could not out the differences between CIVlLIZA110N and be considered by any stretch of the imagination ADVANCED CIVlLIZA110N. Readers who arc to be ~wargamers". Articles suggesting rule unfamiliar with either game will still find Gar) changes for CIVlL1ZA110N have occasionally Rapanos' article interesting for historical reas been published, and house rules abound, but no ons, but CIVILlZAllON players will fUld ill systemic revision of CJVJUZAI10N has been invaluable in helping them know what to remem attempted. Until now. ber and what to forget. WEST T¥IO articles which should be of genenJ "Advanced" CIVILIZATION interest are -The Wrath of the Gods· (p.26) and -Civilization Cards" (p.31), which discuss EXTENSION The term ~advanced- is likely Il misnomer. "Enhanced" might have been more accurate, but several essential aspects of the game. The ADVANCED CNTUZAI10N follows a tradition insights in these articles are definitely not which is already established at Avalon Hill. exhaustive, but provide food for thought. MAP A somewbat different approach to the game is When a product is based on an existing game, found in -Through the Labyrinth - (p .20) and • A but goes beyond it, it is appropriate to use the For some time players of the popular Study in Contrasts- (p.28), which discuss the term "advanced-, as in ADVANCED SQUAD CIV1LfZATIONhave been looking for ways LEADER or ADVANCED TlURD RETCH. This pili)' of Crete, Egypt and Africa. ADVANCED to impro'Ve this already~classic game. -

BATTLE-SCARRED and DIRTY: US ARMY TACTICAL LEADERSHIP in the MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, 1942-1943 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial

BATTLE-SCARRED AND DIRTY: US ARMY TACTICAL LEADERSHIP IN THE MEDITERRANEAN THEATER, 1942-1943 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Steven Thomas Barry Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Allan R. Millett, Adviser Dr. John F. Guilmartin Dr. John L. Brooke Copyright by Steven T. Barry 2011 Abstract Throughout the North African and Sicilian campaigns of World War II, the battalion leadership exercised by United States regular army officers provided the essential component that contributed to battlefield success and combat effectiveness despite deficiencies in equipment, organization, mobilization, and inadequate operational leadership. Essentially, without the regular army battalion leaders, US units could not have functioned tactically early in the war. For both Operations TORCH and HUSKY, the US Army did not possess the leadership or staffs at the corps level to consistently coordinate combined arms maneuver with air and sea power. The battalion leadership brought discipline, maturity, experience, and the ability to translate common operational guidance into tactical reality. Many US officers shared the same ―Old Army‖ skill sets in their early career. Across the Army in the 1930s, these officers developed familiarity with the systems and doctrine that would prove crucial in the combined arms operations of the Second World War. The battalion tactical leadership overcame lackluster operational and strategic guidance and other significant handicaps to execute the first Mediterranean Theater of Operations campaigns. Three sets of factors shaped this pivotal group of men. First, all of these officers were shaped by pre-war experiences. -

STRATEGIC APPRAISAL the Changing Role of Information in Warfare

STRATEGIC APPRAISAL The Changing Role of Information in Warfare Edited by ZALMAY M. KHALILZAD JOHN P. WHITE Foreword by ANDREW W. MARSHALL R Project AIR FORCE The research reported here was sponsored by the United States Air Force under contract F49642-96-C-0001. Further information may be obtained from the Strategic Planning Division, Directorate of Plans, Hq USAF. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The changing role of information in warfare / Zalmay M. Khalilzad, John P. White, editors. p. cm. “Prepared for the United States Air Force by RAND's Project AIR FORCE.” “MR-1016-AF.” Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 0-8330-2663-1 1. Military art and science—Automation. I. Khalilzad, Zalmay M. II. White, John P. UG478.C43 1999 355.3 ' 43—dc21 99-24933 CIP RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and deci- sionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opin- ions or policies of its research sponsors. © Copyright 1999 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopy- ing, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permis- sion in writing from RAND. Cover design by Eileen Delson La Russo Published 1999 by RAND 1700 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138 1333 H St., N.W., Washington, D.C. 20005-4707 RAND URL: http://www.rand.org/ To order RAND documents or to obtain additional information, contact Distribution Services: Telephone: (310) 451-7002; Fax: (310) 451-6915; Internet: [email protected] PREFACE The effects of new information technologies are all around us. -

The German Center Party and the League of Nations: International Relations in a Moral Dimension

InSight: RIVIER ACADEMIC JOURNAL, VOLUME 4, NUMBER 2, FALL 2008 THE GERMAN CENTER PARTY AND THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS: INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS IN A MORAL DIMENSION Martin Menke, Ph.D.* Associate Professor, Department of History, Law, and Political Science, Rivier College During the past two decades, scholarly interest in German political Catholicism, specifically in the history of the German Center Party has revived.1 As a spate of recent publication such as Stathis Kalyvas’s The Rise of Christian Democracy in Europe and the collection of essays, Political Catholicism in Europe, 1918-1965, 2 show, this renewed interest in German political Catholicism is part of a larger trend. All of these works, however, show how much work remains to be done in this field. While most research on German political Catholicism has focused on the period before 1918, the German Center Party’s history during the Weimar period remains incompletely explored. One of the least understood areas of Center Party history is its influence on the Weimar government’s foreign policy. After all, the Center led nine of the republic’s twenty cabinets. Karsten Ruppert, for example, relies almost exclusively on Peter Krüger’s Die Außenpolitik der Republik von Weimar,3 which emphasizes the role of Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann almost to the exclusion of all other domestic decision-makers. Weimar’s foreign policy largely consisted of a series of responses to crises caused by political and economic demands made by the victors of the First World War. These responses in turn were determined by the imperatives of German domestic politics. -

Chronik Eines Richtlinienstreites Zwischen Dem Reichskanzler Luther Und Dem Reichsminister Des Auswärtigen, Stresemann, 1925. Z

THEODOR ESCHENBURG CHRONIK EINES RICHTLINIENSTREITES ZWISCHEN DEM REICHSKANZLER LUTHER UND DEM REICHSMINISTER DES AUSWÄRTIGEN, STRESEMANN, 1925 Zur Technik des Regierens im parlamentarischen System 1. Gleich nach Bismarcks Sturz im Jahre 1890 hatte Hugo Preuss, Privatdozent für öffentliches Recht an der Handelshochschule Berlin, in einer Aufsatzreihe eine Reform der Regierungsorganisation im Reich und in Preußen vorgeschlagen. Damals war der Reichskanzler gleichzeitig preußischer Ministerpräsident. Im Reich war er der alleinverantwortliche Minister, dem die Ressortchefs als Staatssekretäre unterstanden, in Preußen hingegen lediglich Vorsitzender einer Kollegialregierung und an deren Beschlüsse gebunden, also auch einer Mehrheitsentscheidung unter worfen. Preuss wollte mit seinem Vorschlag die Nachfolger Bismarcks von der ver antwortlichen Aufsicht über die bei den wachsenden Reichsaufgaben sich rasch und stark ausdehnenden Ressorts entlasten und andererseits ihn in Preußen vom Druck altkonservativer Minister befreien. Deshalb sollten Staatssekretäre im Reich und nunmehr auch in Preußen unter eigener Verantwortung ihre Ressorts leiten. Der Reichs- und preußische Staatskanzler sollte aber die „politische Richtung" be stimmen. Dem Kanzler sollte das Recht des Einblicks in die gesamte Geschäfts führung und eines Vetos gegen jede Maßregel der Ressortverwaltung zustehen. Modell für diesen Vorschlag war nach einem Wort Otto Hintzes das englische Premierministersystem, das sich mehr und mehr in eine „populäre Diktatur um wandelte". Nach -

Squander Cover

The importance and vulnerability of the world’s protected areas Squandering THREATS TO PROTECTED AREAS SQUANDERING PARADISE? The importance and vulnerability of the world’s protected areas By Christine Carey, Nigel Dudley and Sue Stolton Published May 2000 By WWF-World Wide Fund For Nature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund) International, Gland, Switzerland Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must mention the title and credit the above- mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. © 2000, WWF - World Wide Fund For Nature (Formerly World Wildlife Fund) ® WWF Registered Trademark WWF's mission is to stop the degradation of the planet's natural environment and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature, by: · conserving the world's biological diversity · ensuring that the use of renewable natural resources is sustainable · promoting the reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption Front cover photograph © Edward Parker, UK The photograph is of fire damage to a forest in the National Park near Andapa in Madagascar Cover design Helen Miller, HMD, UK 1 THREATS TO PROTECTED AREAS Preface It would seem to be stating the obvious to say that protected areas are supposed to protect. When we hear about the establishment of a new national park or nature reserve we conservationists breathe a sigh of relief and assume that the biological and cultural values of another area are now secured. Unfortunately, this is not necessarily true. Protected areas that appear in government statistics and on maps are not always put in place on the ground. Many of those that do exist face a disheartening array of threats, ranging from the immediate impacts of poaching or illegal logging to subtle effects of air pollution or climate change. -

Klassenkompromiß Und Wiederkehr Des Klassenkonfliktes in Der Weimarer Republik''

David Abraham Klassenkompromiß und Wiederkehr des Klassenkonfliktes in der Weimarer Republik'' Aus der Perspektive der Linken scheint die Geschichte des Sozialismus und der organisier ten Arbeiterbewegung während der Weimarer Republik zumeist eine kurze und schmerzli che Episode - eine permanente Abwä1tskurve, die durch V errat, Niederlage, Repression und schließlich durch den Triumph des Faschismus gekennzeichnet ist. Die Unter drückung einer verkümmerten Arbeiterrevolution von 1918-19, der gleichzeitige reformi stische »Ausverkauf« durch die überwältigende Mehrheit der SPD, eine Reihe selbstzerstö• rerischer Unternehmungen einer unreifen Kommunistischen Partei, die früh von der Komintern »koordiniert« wurde, Heerscharen von pauperisierten Brechtschen Arbeitern, die die Rechnung für die Niederlage des Deuschten Imperialismus zu begleichen haben, und letztlich der Aufstieg und Sieg des Nationalsozialismus - alle diese Vorstellungen ha ben unsere Sicht des tatsächlichen Status der organisierten Arbei.terbewegung während der Weimarer Jahre verschwimmen lassen, insbesondere während der stabilen Jahre der Repu blik zwischen 1924-30. Tatsächlich war die politische und ökonomische Situation vieler deutscher Arbeiter während dieser Jahre zwischen der endgültigen Niederlage verschiede ner linker Aufstände und dem Aufstieg des Massenfaschismus viel günstiger als allgemein angenommen wird. Von liberalen Beobachtern, die sich mit dem augenscheinlichen Phä• nomen des Korporatismus und unserer eigenen »neokorporatistischen« Ära beschäftigen, -

Corporate Diplomacy

Corporate Diplomacy The Strategy for a Volatile, Fragmented Business Environment Ulrich Steger International Institute for Management Development (IMD) withaforewordby Antony Burgmans CEO, Unilever Corporate Diplomacy Corporate Diplomacy The Strategy for a Volatile, Fragmented Business Environment Ulrich Steger International Institute for Management Development (IMD) withaforewordby Antony Burgmans CEO, Unilever Copyright#2003JohnWiley&SonsLtd,TheAtrium,SouthernGate,Chichester, WestSussexPO198SQ,England Telephone(+44)1243779777 Email(forordersandcustomerserviceenquiries):[email protected] VisitourHomePageonwww.wileyeurope.comorwww.wiley.com AllRightsReserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedinaretrieval systemortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronic,mechanical,photocopying, recording,scanningorotherwise,exceptunderthetermsoftheCopyright,Designsand PatentsAct1988orunderthetermsofalicenceissuedbytheCopyrightLicensingAgency Ltd,90TottenhamCourtRoad,LondonW1T4LP,UK,withoutthepermissioninwritingof thePublisher.RequeststothePublishershouldbeaddressedtothePermissionsDepartment, JohnWiley&SonsLtd,TheAtrium,SouthernGate,Chichester,WestSussexPO198SQ, England,[email protected],orfaxedto(+44)1243770620. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional -

Natural & Cultural Resources Master Plan

Visionary leaders a century ago realized how important it was to set aside natural, Message from the open space to be enjoyed by everyone. Though our county has grown into one of the densest urban areas in the country, we are never more than a short trip away from President nature. We are benefactors of what has grown into 69,000 acres of land containing some of the most diverse plant and wildlife species in North America. I have spent a lot time over the years learning about the prairies, wetlands, savannas and forest habitats that surround us. Each time I enjoy an activity with my grandchildren surrounded by nature, it is clear we have a responsibility not to squander this rich inheritance, especially for future generations. The Natural and Cultural Resources Master Plan was created to guide our restoration efforts into the next century. This document provides an assessment of the preserves and the framework needed to implement our ambitious goals of restoring 30,000 acres of land in 25 years. I want to thank the Prairie Research Institute at the University of Illinois for developing this comprehensive plan in partnership with the Forest Preserves of Cook County. PRI is a leading organization with researchers from multiple disciplines who work to promote natural and cultural resource sustainability. Their skills and perspective have helped us realize these first steps and I look forward to our ongoing partnership. Toni Preckwinkle President, Forest Preserves of Cook County The Natural and Cultural Resources Master Plan is an invaluable tool that will help steer Message from the the Forest Preserves of Cook County into a new era. -

Modell Deutschland As an Interdenominational Compromise

Program for the Study of Germany and Europe Working Paper No. 00.3 Modell Deutschland as an Interdenominational Compromise Philip Manow Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies Cologne [email protected] Abstract: Usually, Germany’s social market economy is understood to embody a compromise between a liberal market order and a corporatist welfare state. While this reading of the German case is certainly not entirely wrong, this paper argues that only if we account for the close intellectual correspondence between lutheran Protestantism and economic liberalism on the one hand and between Catholicism and welfare corporatism on the other, can we fully comprehend the nature of the German post-war compromise. In particular, this perspective allows to better explain the anti-liberal undercurrents of Germany’s soziale Marktwirtschaft. It was especially the role which Protestant Ordoliberals ascribed to the state in upholding economic order and market discipline which accounts for the major difference between ‘classic’ and ‘German-style’ economic liberalism. Yet, the postwar economic order did not represent a deliberately struck compromise between the two major Christian denominations. Rather, Germany’s social market economy was the result of the failure of German Protestant Ordoliberals to prevent the reconstruction of the catholic Bismarckian welfare state after the authoritarian solution, which Ordoliberals had endorsed so strongly up until 1936 and from which they had hoped the re-inauguration of Protestant hegemony, had so utterly failed. Since the ordoliberal doctrine up to the present day lacks a clear understanding of the role of the corporatist welfare state within the German political economy, its insights into the functioning logic of German capitalism have remained limit. -

Dissertationcarinasimon.Pdf (3.051Mb)

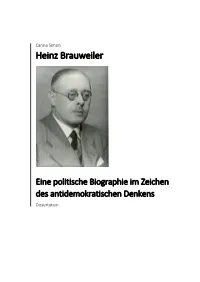

Carina Simon Heinz Brauweiler Eine politische Biographie im Zeichen des antidemokratischen Denkens Dissertation Heinz Brauweiler Eine politische Biographie im Zeichen des antidemokratischen Denkens Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades der Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) eingereicht im Fachbereich Gesellschaftswissenschaften an der Universität Kassel vorgelegt von Carina Simon 2016 Disputation am 22.5.2017 Danksagung Ich möchte an dieser Stelle die Gelegenheit nutzen, einigen Menschen meinen Dank auszusprechen, ohne deren Hilfe die Abgabe meiner Doktorarbeit nur schwer vorstellbar gewesen wäre. An erster Stelle danke ich meinen Betreuern Professor Dr. Winfried Speitkamp und Professor Dr. Jens Flemming. Letzterer hat mich von Beginn meines Studiums an begleitet. Ohne Professor Dr. Flemming wäre meine Begeisterung für das Studium der Geschichte und die Entscheidung für eine Dissertation nie in dem Maße vorstellbar gewesen. Er hat mir immer mit Rat und Tat zur Seite gestanden, mir geholfen, auch wenn es einmal schwerere Phasen gab. Darüber hinaus danke ich Herrn Professor Dr. Dietmar Hüser und Herrn Professor Dr. Friedhelm Boll sowie den Mitarbeitern und Mitarbeiterinnen des Fachbereichs Geschichte der Universität Kassel, hier ganz besonders Silke Stoklossa-Metz. Darüber hinaus möchte ich mich bei Dr. Christian Wolfsberger (✝) und Gerd Lamers vom Stadtarchiv Mönchengladbach für ihre Hilfe bedanken; sowie bei allen Mitarbeitern und Mitarbeiterinnen der verschiedenen Archive und Bibliotheken, die ich zu Recherchezwecken aufgesucht habe. Weiterhin danken möchte ich der B. Braun Melsungen AG für ihre finanzielle Unterstützung im Rahmen meines Stipendiums, was mir über einen langen Zeitraum ein sorgenfreies Arbeiten ermöglichte. Danken möchte ich vor allem meiner Familie, hier vor allem meinen Eltern, Hella und Alexander Simon und meinem Bruder Christopher Simon. -

Choosing Lesser Evils: the Role of Business in the Development of the German Welfare State from the 1880S to the 1990S

Department of Political and Social Sciences Choosing Lesser Evils: The Role of Business in the Development of the German Welfare State from the 1880s to the 1990s Thomas Paster Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Florence, June 2009 EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE Department of Political and Social Sciences Choosing Lesser Evils: The Role of Business in the Development of the German Welfare State from the 1880s to the 1990s Thomas Paster Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Examining Board: Professor Sven Steinmo, EUI (supervisor) Professor Martin Rhodes, Univ. of Denver & ex-EUI (co-supervisor) Professor Colin Crouch, Univ. of Warwick Business School Professor Anke Hassel, Hertie School of Governance, Berlin © 2009, Thomas Paster No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author. b Acknowledgements This thesis has been long in the making and it seems almost like a miracle that I am now finally bringing this big project to an end. Late in my second year at the EUI I returned from a field mission with a disillusioning sense that my original hypotheses, which centered on presumed sectoral variations in interests, were either untestable or unfounded. What I found empirically turned out to be at odds with my initial expectations in important ways and pointed me to the possibility that the organizations I intended to study were following a very different logic of reasoning than what I had initially assumed.