Honda Lake Elsinore Project CULTURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Right Thing to Do: Returning Land to the Wiyot Tribe

THE RIGHT THING TO DO: RETURNING LAND TO THE WIYOT TRIBE by Karen Elizabeth Nelson A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts In Sociology May, 2008 THE RIGHT THING TO DO: RETURNING LAND TO THE WIYOT TRIBE by Karen Elizabeth Nelson Approved by the Master’s Thesis Committee: Jennifer Eichstedt, Committee Chair Date Elizabeth Watson, Committee Member Date Judith Little, Committee Member Date Jennifer Eichstedt, Graduate Coordinator Date Chris Hopper, Interim Dean for Research and Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT THE RIGHT THING TO DO: RETURNING LAND TO THE WIYOT TRIBE Karen Elizabeth Nelson In 2004, the Eureka City Council legally returned forty acres of Indian Island to the Wiyot tribe. This return occurred one hundred and forty four years after the Indian Island massacre. This research explores the returning of sacred tribal land in the context of collective apologies and reconciliations after generations of Native genocide. The significance of this case study includes a detailed narration of how the land transfer occurred and more importantly why it was labeled “the right thing to do” by Eureka City Council members and staff. This case study was examined with a grounded theory methodology. Using no hypotheses, the research and the research methodology unfolded in a non-linear process, letting the research speak for itself. Detailed interviews and a review of documents were used to qualify and quantify this unique community based social act. The results of this case study include how and why the Eureka City Council returned forty acres of Indian Island to the Wiyot people. -

1917 Gossip Column & News Articles

TEMECULA VALLEY HISTORICAL SOCIETY 1917 Gossip Column & News Articles January 5, 1917 After spending a few days in Los Angeles, Paul Clark of the Pauba Ranch returned home the first of the week. Eila Kolb, who is attending the Riverside business college, spent the holidays at home. After spending a very pleasant visit with his parents Frank Ramos returned to Riverside last Saturday to continue his studies. Dr. L. L. Roripaugh of Auld was in town the other day treating his friends to cigars. The doctor being newly wed his many friends wish him and his bride a very happy future. Curtis Stevenson and wife of Pechanga were first of the week visitors at the Ventura Arviso home. Francis McCarrell drove over here after freight for the Aguanga store. E. C. Tripp of Aguanga was in town the last of the week hauling lumber. Mrs. John B. Kelly returned home Saturday from Los Angeles where she had a pleasant two weeks' visit with her sister, Mrs. John N. Carr. Charles Swain and Juan Munoa have moved to the Harvey place, where they will plant barley this winter. The dance given at the Bank hall Saturday night was attended by several from the surrounding country. D. S. Woosley of Escondido was in town the first of the week doing some missionary work. A large number of the young people from town attended the dance at the Murrieta Hot Springs. George Studley has succeeded J. S. Felix as foreman of the cowboys at the Pauba Ranch. Mr. Studley has been a steady hand at the ranch for four years. -

Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/59b7c0n9 Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 9(1) ISSN 0191-3557 Author Cohen, Bill Publication Date 1987-07-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of California and Great Basin Antliropology Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 4-34 (1987). Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California BILL COHEN, 746 Westholme Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90024. OANDPAINTINGS created by native south were similar in technique to the more elab ern Californians were sacred cosmological orate versions of the Navajo, they are less maps of the universe used primarily for the well known. This is because the Spanish moral instruction of young participants in a proscribed the religion in which they were psychedelic puberty ceremony. At other used and the modified native culture that times and places, the same constructions followed it was exterminated by the 1860s. could be the focus of other community ritu Southern California sandpaintings are among als, such as burials of cult participants, the rarest examples of aboriginal material ordeals associated with coming of age rites, culture because of the extreme secrecy in or vital elements in secret magical acts of which they were made, the fragility of the vengeance. The "paintings" are more accur materials employed, and the requirement that ately described as circular drawings made on the work be destroyed at the conclusion of the ground with colored earth and seeds, at the ceremony for which it was reproduced. -

Carmel Canine Sports Center Project Environmental Impact Report (PLN13052)

Proposal to Prepare the Carmel Canine Sports Center Project Environmental Impact Report (PLN13052) Prepared by: Prepared for: AMEC Environment & Infrastructure, Inc. Monterey County 104 West Anapamu Street, Suite 204A RMA – Planning Department Santa Barbara, California, 93101 168 West Alisal Street, 2nd Floor Phone (805) 962-0992 Fax (805) 966-1706 Salinas, California, 93901 amec.com June 13, 2014 2 | P a g e June 13, 2014 Mr. Steve Mason, Associate Planner RMA – Planning Department County of Monterey 168 West Alisal Street, 2nd Floor Salinas, CA 93901-2439 Subject: Proposal to Prepare an Environmental Impact Report for the Carmel Canine Sports Center Project – PLN130352 Dear Mr. Mason: AMEC Environment & Infrastructure, Inc. (AMEC) is pleased to provide the attached revised proposal to prepare an Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for the Carmel Canine Sports Center project. AMEC has assembled a strong team with directly relevant experience for this type of project. Highlights of our team’s capabilities and strengths include: . A Project Manager with substantial experience in environmental review and permitting of controversial projects in jurisdictions with high constituency involvement, including current management of a Project EIR in the Del Monte Forest Planning Area of Monterey County. A team with substantial experience preparing EIRs addressing controversial and complex development projects, including innovative approaches to water resource management, habitat and sensitive species compliance, and noise and traffic mitigation. A team with in-depth knowledge of federal, state, and local regulatory standards, processes, and requirements. AMEC’s team would conduct work from our Santa Barbara and San Francisco offices, while Central Coast Transportation Consulting, AMEC’s subconsultant for traffic analysis, would be based in Morro Bay. -

Thomas Coulter's 1832 Visits

Thomas Coulter’s Visits in 1832 the “narrow valley” of the San Luis Rey River, then crossed the Lake Hen- shaw plain and proceeded down the San Felipe valley to Vallecitos. En- Thomas Coulter (1793-1843) first came to the San Diego region in during hot days without water or much forage, the group finally passed April 1832, accompanying a group of Americans who purchased mules the Algodones Dunes and arrived south of the confluence of the Gila and and horses from the California missions and were driving them east to Colorado Rivers around May 8, 1832. Coulter camped ten days near pres- be sold in the United States [43]. He was 38 years old. He had arrived in ent-day Yuma while the Americans worked strenuously to ford the river Monterey six months earlier after working for five years in Mexico. at its seasonal height. From there he wrote a letter to de Candolle’s son, Coulter grew up Presbyterian in northeast Ireland and in 1820 be- dated May 16, 1832, saying “...here is nothing, nothing. This is truly the came a medical doctor or surgeon [44]. In 1822 he studied botany at kingdom of desolation” [49]. He then turned back west, accompanying the Jardin des Plantes in Paris and in Geneva under Augustin-Pyramus de Young, Warner, Kit Carson’s older brother Moses Carson, Isaac Williams Candolle (1778–1841), his mentor. In 1824 he took a position as surgeon and a few other men, reaching Pala around May 27. He returned to San for a British mining company and moved to central Mexico. -

General Plan Amendment No. 1208 Lakeland Village Community Plan

FINAL INITIAL STUDY/MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION General Plan Amendment No. 1208 Lakeland Village Community Plan State Clearinghouse No. 2020050501 Lead Agency: RIVERSIDE COUNTY Planning Department 4080 Lemon Street, 12th Floor, Riverside, CA 92501 Contact: Mr. Robert Flores 951.955.1195 Prepared by: MICHAEL BAKER INTERNATIONAL 3536 Concours Street Ontario, California 91764 Contact: Mr. Peter Minegar, CEP-IT 951.506.3523 June 2020 JN 155334 This document is designed for double-sided printing to conserve natural resources. Section I Initial Study/ Mitigated Negative Declaration General Plan Amendment No. 1208 Lakeland Village Community Plan COUNTY OF RIVERSIDE ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FORM: INITIAL STUDY Environmental Assessment (CEQ / EA) Number: N/A Project Case Type (s) and Number(s): General Plan Amendment No. 1208 (GPA No. 1208) Lead Agency Name: Riverside County Planning Department Address: 4080 Lemon Street, P.O. Box 1409, Riverside, CA 92502-1409 Contact Person: Robert Flores (Urban and Regional Planner IV) Telephone Number: 951-955-1195 Applicant’s Name: N/A Applicant’s Address: N/A I. PROJECT INFORMATION Project Description: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT The County of Riverside is composed of approximately 7,300 square miles, bounded by Orange County to the west, San Bernardino County to the north, the State of Arizona to the east, and San Diego and Imperial Counties to the south. Development for the unincorporated County is guided by the Riverside County General Plan, which was last comprehensively updated and adopted in December 2015. The Riverside County General Plan is divided into 19 Area Plans covering most of the County (refer to Exhibit 1, Riverside County Area Plans). -

Waterman 1934: 3-4

a state society (i.e., Euro-American) in the historic past, manu- factured either by direct political or indirect economic pressures (1975). Thus, the concept "triblet" may, indeed, describe the situation in the entire Country. To reiterate, in California, triblets were organized around a central community for a number of nearby sub-ordinate settlements. However, in northwestern California, political organization was characterized by extreme fractionalism; the triblet was a loosely connected set of separate settlements, and people clustered in a town or village which did not have the sense of cohesiveness and continuity of other areas. Individualism, or atomism, was the rule for the Tolowa, Hupa, Chil- ula, Wiyot, Karok, and Yurok. Within certain class boundaries, north- western California was characterized by a man struggling for himself and his immediate family--competition rather than cooperation was the ideal (Bean 1974). Factionalism of the typical triblet pattern was reflected in other aspects of northwestern California culture. For instance in regard to marriage practices: ... apart from the generic tendency to seek wives 'downstream,' the Tolowa and Karok sought wives not only in the immediately adjacent Yurok dis- tricts, but also to some degree in farther ones; and the Yurok reciprocated correspondingly. The Hupa and Chilula, on the contrary, exchanged wives and husbands with the Yurok almost exclu- sively in the Weitspus district. This differ- ence seems to be connected with the Tolowa and Karok being on the upstream-downstream line, as the Yurok construe the world, but the Hupa and Chilula living in a 'side-stream' or 'up-hill' direction. Intercourse and relations evidently flowed most freely along the main thoroughfare of the Klamath and its coastwise 'continuation' (Waterman 1934: 3-4). -

FY 2019-2020 and FY 2020-21 Budget

BUDGET Elsinore Valley Municipal Water District FISCAL YEAR 2020 AND 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL MANAGER BUDGET HIGHLIGHTS 4 GFOA Distinguished Budget Presentation Award 15 CSMFO Certificate of Award for Excellence in Operating Budget 16 BUDGET NARRATIVE 17 Description of the District and the Budget Process 18 Operating Revenues and Expenditures 24 Non-Operating Revenues and Expenditures 29 AUTHORIZED POSITIONS 36 Organization Chart 37 Summary of Changes in Authorized Positions 38 Authorized Position Listing 41 STRATEGIC PLAN & DEPARTMENT ACCOMPLISHMENTS 46 Strategic Plan 47 General Management 49 Business Services Division 53 Engineering & Operations Division 58 CAPITAL OUTLAYS 63 Significant Capital Outlays 64 Fiscal Year 2020 65 Fiscal Year 2021 66 CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROJECTS 67 Capital Improvement Projects 68 Fiscal Year 2020 & 2021 76 BUDGET STATEMENTS 79 Fund Structure 80 List of Funds/Programs 82 Elsinore Valley Municipal Water District 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Relationship between Divisions, Departments, Sections, and Funds 87 Summary of Revenues & Operating Transfers In/Out All Funds 88 Consolidated Statement of Sources and Uses 89 Statement of Sources and Uses of Funds Fiscal Year 2020 90 Statement of Sources and Uses of Funds Fiscal Year 2021 106 Consolidated Statement of Income 122 Computation of Debt Coverage 123 Debt Repayment Requirements & Sources Fiscal Year 2020 & 2021 124 Funding and Cash Flow Diagram 127 Significant Changes in Fund Balances 128 Schedule of Changes in Fund Balance, Fiscal Year 2020 129 Schedule of Changes -

Notice Concerning Copyright Restrictions

NOTICE CONCERNING COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS This document may contain copyrighted materials. These materials have been made available for use in research, teaching, and private study, but may not be used for any commercial purpose. Users may not otherwise copy, reproduce, retransmit, distribute, publish, commercially exploit or otherwise transfer any material. The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specific conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be "used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research." If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. Geothermal Resources Council, TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 10, September 1986 GEOTHERMAL EXPLORATION IN THE VICINITY OF LAKE ELSINORE, SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Brian N. Damiata and Tien-Chang Lee Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics University of California, Riverside, CA 92521 ABSTRACT Geothermal exploration in the Lake Elsinore area has primarily focused near a cross fault which acts as a conduit for thermal water. Flow testing of an exploratory hole indicates an ani- sotropic aquifer with a maximum transmissivity IO mi axis oriented along the fault striking N 11" E. Thermal water migrates laterally throughout the downtown area along a zone of enhanced transmissivity associated with the fault. -

SAN DIEGO COUNTY NATIVE PLANTS in the 1830S

SAN DIEGO COUNTY NATIVE PLANTS IN THE 1830s The Collections of Thomas Coulter, Thomas Nuttall, and H.M.S. Sulphur with George Barclay and Richard Hinds James Lightner San Diego Flora San Diego, California 2013 SAN DIEGO COUNTY NATIVE PLANTS IN THE 1830s Preface The Collections of Thomas Coulter, Thomas Nuttall, and Our knowledge of the natural environment of the San Diego region H.M.S. Sulphur with George Barclay and Richard Hinds in the first half of the 19th century is understandably vague. Referenc- es in historical sources are limited and anecdotal. As prosperity peaked Copyright © 2013 James Lightner around 1830, probably no more than 200 inhabitants in the region could read and write. At most one or two were trained in natural sciences or All rights reserved medicine. The best insights we have into the landscape come from nar- No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form ratives of travelers and the periodic reports of the missions’ lands. They without permission in writing from the publisher. provide some idea of the extent of agriculture and the general vegeta- tion covering surrounding land. ISBN: 978-0-9749981-4-5 The stories of the visits of United Kingdom naturalists who came in Library of Congress Control Number: 2013907489 the 1830s illuminate the subject. They were educated men who came to the territory intentionally to examine the flora. They took notes and col- Cover photograph: lected specimens as botanists do today. Reviewing their contributions Matilija Poppy (Romneya trichocalyx), Barrett Lake, San Diego County now, we can imagine what they saw as they discovered plants we know. -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 98/Monday, May 24, 2021/Notices

27892 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 98 / Monday, May 24, 2021 / Notices 225. Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of 273. Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation Commission (‘‘Commission’’) Michigan 274. Tonkawa Tribe of Oklahoma determines, pursuant to the Tariff Act of 226. Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian 275. Tonto Apache Tribe 1930 (‘‘the Act’’), that revocation of the Community 276. Torres Martinez Desert Cahuilla countervailing duty and antidumping 227. Samish Indian Tribe Indians duty orders on certain steel grating from 228. San Carlos Apache Tribe 277. Tulalip Tribes of Washington China would be likely to lead to 229. San Manual Band of Mission 278. Tule River Tribe continuation or recurrence of material Indians 279. Tunica-Biloxi Indians of Louisiana injury to an industry in the United 230. San Pasqual Band of Diegueno 280. Tuolumne Band of Me-Wuk States within a reasonably foreseeable Mission Indians Indians time. 231. Santa Rosa Rancheria Tachi-Yokut 281. Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Tribe Indians Background 232. Santa Ynez Band of Chumash 282. Twenty-Nine Palms Band of The Commission instituted these Mission Indians Mission Indians reviews on October 1, 2020 (85 FR 233. Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe 283. United Auburn Indian Community 61981) and determined on January 4, 234. Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa 284. Upper Sioux Community 2021 that it would conduct expedited Indians 285. Upper Skagit Indian Tribe of reviews (86 FR 19286, April 13, 2021). 235. Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians Washington The Commission made these 236. Seminole Nation of Oklahoma 286. Ute Mountain Ute Tribe determinations pursuant to section 237. -

Sample Ballot

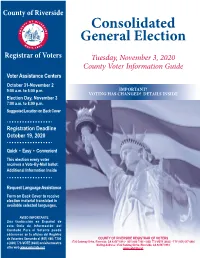

County of Riverside Consolidated General Election Registrar of Voters Tuesday, November 3, 2020 County Voter Information Guide Voter Assistance Centers October 31-November 2 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. IMPORTANT! VOTING HAS CHANGED! DETAILS INSIDE Election Day, November 3 7:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. Suggested Location on Back Cover Registration Deadline October 19, 2020 Quick • Easy • Convenient This election every voter receives a Vote-By-Mail ballot. Additional Information Inside Request Language Assistance Form on Back Cover to receive election material translated in available selected languages. AVISO IMPORTANTE Una traducción en Español de esta Guía de Información del Condado Para el Votante puede obtenerse en la oficina del Registro de Votantes llamando al (951) 486- 7200 COUNTY OF RIVERSIDE REGISTRAR OF VOTERS o (800) 773-VOTE (8683) o visite nuestro 2720 Gateway Drive, Riverside, CA 92507-0918 • (951) 486-7200 • (800) 773-VOTE (8683) • TTY (951) 697-8966 Mailing Address: 2724 Gateway Drive, Riverside, CA 92507-0918 sitio web www.voteinfo.net www.voteinfo.net THIS ELECTION VOTING IS DIFFERENT VOTE-BY-MAIL Vote at home using your Vote-By-Mail ballot No Postage Required Quick, easy, convenient... from the comfort of your home! OR BALLOT DROP-OFF LOCATION Drop off your ballot at any of the Ballot Drop-off locations in Riverside County No Postage Required See inside... for a list of drop-off locations throughout Riverside County! OR VOTER ASSISTANCE CENTER Vote in-person at any of the Voter Assistance Centers in Riverside County October 31-November 2, from 9:00 a.m.