ADINKU-THESIS-2020.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Floyd's Death and Impact ABC News

Timeline: George Floyd’s Death and Impact ABC News - June 3rd 2020 May 25th • George Floyd Dies in Police Custody -George Floyd, 46, is arrested shortly after 8 p.m. after allegedly using a fake $20 bill at a local Cup Foods. He dies while in police custody. A disturbing cellphone video later posted to Facebook shows an officer pinning Floyd to the ground with his knee on Floyd’s neck while a handcuffed Floyd repeats “I can’t breathe.” The video goes viral. 26th • Responding Officers are fired as Pro- tests begin in Minneapolis 27th • Protests begin in other cities, including Los Angeles and Memphis 28th • Minnesota Governer Activates the Na- tional Guard 29th • An officer, Derek Chauvin, is arrested and charged with third degree murder June in Floyd’s death 1st • Results of an independent autopsy find that Floyd’s death was due to asphyx- iation - this runs contrary to the police autopsy, which said the death was due to underlying health conditions Floyd had • A Civil Rights Charge is filed against 2nd Minneapolis Police • three more officers are charged for 3rd aiding and abetting second degree murder. Chauvin’s charge is adjusted to second de- gree murder What’s next? Demonstrators continue to bat- tle white supremacy and police brutality. Groups call to defund, divest, and abolish po- lice across the U.S. and abroad. Abolitionists continue to call for the Abolition of prisons. Why The Small Protests In Small Towns Across America Matter by Anne Petersen Dorian Miles arrived in Havre, Montana — a windy farm town, population 9,700, along what’s known as Montana’s Hi-Line — just five months ago, a young man from Georgia coming to play football for Montana State University–Northern. -

Dismantling Racism Task Force

CHRIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH Dismantling Racism Task Force Resource Materials 10/25/2020 The Dismantling Racism Task Force has compiled a list of recommended educational materials in the form of books, film, videos, podcasts, et.al. These materials are categorized based on their subject matter using a legend of color-coded, geometric icons which is included with this collection. For convenience, a terminology section is also included. History, despite its wrenching pain, Cannot be unlived, and if faced with courage, Need not be lived again. - Maya Angelou, “On the Pulse of Morning” 1 Books Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents Author: Isabel Wilkerson (2020) 388 pages (469 pages with notes, etc.) Brilliant, revealing, and impressively-researched, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents is an eye-opening story of people and history and how lives and behaviors are influenced by the rigid hierarchy of caste. Pulitzer Prize winning author, instructor and lecturer Isabel Wilkerson uses the stories of real people to show how America throughout its history, and still today, has been shaped by a hidden caste system. This rigid hierarchy of human rankings not only influences people’s lives but the nation’s fate. She shows us that racism, which resides within the invisible caste structure in America, is so ingrained that it is autonomic in expression and mostly goes unnoticed or unchallenged. Gifted with great narrative and literary power, Isabel Wilkerson offers a new perspective on American history while linking and illustrating the caste systems of America, India and Nazi Germany. That Germany used America as a model for its treatment of Jewish people is chilling. -

Black Panther Toolkit! We Are Excited to Have You Here with Us to Talk About the Wonderful World of Wakanda

1 Fandom Forward is a project of the Harry Potter Alliance. Founded in 2005, the Harry Potter Alliance is an international non-profit that turns fans into heroes by making activism accessible through the power of story. This toolkit provides resources for fans of Black Panther to think more deeply about the social issues represented in the story and take action in our own world. Contact us: thehpalliance.org/fandomforward [email protected] #FandomForward This toolkit was co-produced by the Harry Potter Alliance, Define American, and UndocuBlack. @thehpalliance @defineamerican @undocublack Contents Introduction................................................................................. 4 Facilitator Tips............................................................................. 5 Representation.............................................................................. 7 Racial Justice.............................................................................. 12 » Talk It Out.......................................................................... 17 » Take Action............................................................................ 18 Colonialism................................................................................... 19 » Talk It Out.......................................................................... 23 » Take Action............................................................................24 Immigrant Justice........................................................................25 » -

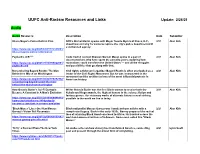

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21 Audio Audio Resource Description Date Submitter Ithaca Mayor's Police Reform Plan NPR's Michel Martin speaks with Mayor Svante Myrick of Ithaca, N.Y., 2/21 Alan Kirk about how and why he wants to replace the city's police department with a civilian-led agency. https://www.npr.org/2021/02/27/972145001/ ithaca-mayors-police-reform-plan Payback's A B**** Code Switch co-host Shereen Marisol Meraji spoke to a pair of 2/21 Alan Kirk documentarians who have spent the past two years exploring how https://www.npr.org/2021/01/14/956822681/ reparations could transform the United States — and all the struggles paybacks-a-b and possibilities that go along with that. Remembering Bayard Rustin: The Man Civil rights activist and organizer Bayard Rustin is often overlooked as a 2/21 Alan Kirk Behind the March on Washington leader of the Civil Rights Movement. But he was instrumental in the movement and the architect of one of the most influential protests in https://www.npr.org/2021/02/22/970292302/ American history. remembering-bayard-rustin-the-man- behind-the-march-on-washington How Octavia Butler's Sci-Fi Dystopia Writer Octavia Butler was the first Black woman to receive both the 2/21 Alan Kirk Became A Constant In A Man's Evolution Nebula and Hugo awards, the highest honors in the science fiction and fantasy genres. Her visionary works of alternate futures reveal striking https://www.npr.org/2021/02/16/968498810/ parallels to the world we live in today. -

Fall 2017 Best-Selling Titles IPG – Fall 2017

Fall 2017 Best-Selling Titles IPG – Fall 2017 9789888341030 9789888240654 9789888341184 9789888341207 9781936669479 9781936669455 9780975958001 9781936261376 9782924217795 9781936261277 9780996099936 9781933916972 9781405266710 9781405279291 9781936607365 9789888341016 99781940842011 99781940842097 99789888240494 9781629631103 9781555917241 9789888240937 9789888341047 9789888341375 9781884734724 IPG – Fall 2017 Best-Selling Titles 9781613749418 9781613736012 9781613736371 9781613734308 9781613731789 9781556520747 9781613743416 9781613735329 9781892005281 9781613736791 9780996864916 9781786695697 9780918172020 9781936218219 9781613731024 9781629371580 9781629371146 9781629373478 9781629374444 9781629372839 9781613734995 9781926760681 9781910496596 9781910904121 9781910904053 Fall 2017 Entertainment ����������������������������������������� 1–10 Pop Culture & Science ������������������������� 11–13 History & Politics ����������������������������������� 14–30 Sports ��������������������������������������������������� 31–50 Travel ���������������������������������������������������� 51–56 Religion ������������������������������������������������ 57–62 Biography & Autobiography ������������������� 63–66 Graphic Novels �������������������������������������� 67–75 Fiction �������������������������������������������������� 76–98 Poetry ���������������������������������������������������������99 Cooking �������������������������������������������� 100–104 Crafts & Hobbies ������������������������������� 105–113 Textile & Design �������������������������������� -

In Absentia: the Lost Ones of America's/Motown's

IN ABSENTIA: THE LOST ONES OF AMERICA’S/MOTOWN’S REVOLUTION(S) By Joyce-Zoë Farley A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of African American and African Studies — Doctor of Philosophy 2020 ABSTRACT IN ABSENTIA: THE LOST ONES OF AMERICA’S/MOTOWN’S REVOLUTION(S) By Joyce-Zoë Farley In Absentia: The Lost Ones of America’s/Motown’s Revolution(s) is a non-traditional documentary dissertation film contesting and adding to the history of Sunday, July 23, 1967— the 1967 Detroit Insurrection—from Black residents and eyewitnesses using their oral history testimonies. This unorthodox undertaking uses a collection of detailed video-recorded, critical ethnographic, thematic life history oral histories from thirty residents, with ten participants selected for the first part, who survived, participated, chronicled, and/or attempted to restore law and order during the chaos. Interviewees assess, challenge, correct, and add to the metanarrative of urban uprising and the Detroit rebellion, which is overshadowed by an abundance of misinterpretations of Black life in the city, media perversions of Black agency and performance, and critiques of rioting rhetoric. Copyright by JOYCE-ZOË FARLEY 2020 This is for the city of Detroit, the summer interning at WXYZ ABC 7 Detroit, and its wonderful residents who provided me with an education, a project, and a career for a lifetime. To my incredible village of family, friends, fictive kin, loved ones, and the list goes on. THANK YOU! In remembrance of The ancestors Maggie Ward (my paternal grandmother) Egbert M. Kirnon, Jr. (my maternal grandfather) Lenora Greene Morris (my fictive kin grandmother and childhood babysitter in Brooklyn, NY) Edward Brazelton Jr. -

October 2020 Volume 86, Number 5 Topics September–October 2020

Talking Book Topics Free Matter for the PIMMS Blind or Handicapped ISSN 0039‑9183 PO Box 9150 Melbourne, FL 32902-9150 Talking Book September–October 2020 Volume 86, Number 5 Topics September–October 2020 November–December 2015 10/01/20: CA5173 Like us on www.loc.gov/nls TBTSepOct2020_coverFinal.indd 1 8/17/2020 4:00:42 PM Need help? Your local cooperating library is always the place to start. For general information and to order books, call 1-888-NLS-READ (1-888-657-7323) to be connected to your local cooperating library. To find your library, turn to the email and phone numbers on thefinal pages of this publication, or visit www.loc.gov/nls and select “Find Your Library.” To change your Talking Book Topics subscription, complete the form on the inside back cover and mail it to your local cooperating library. Get books fast from BARD About Talking Book Topics Most books and magazines listed in Talking Book Topics, published in audio, large Talking Book Topics are available to print, and online, is distributed free to people eligible readers for download on the unable to read regular print and is available NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download in an abridged form in braille. Talking Book (BARD) site. To use BARD, contact Topics lists a selection of titles recently added your local cooperating library or visit to the NLS collection. The entire collection, nlsbard.loc.gov for more information. with hundreds of thousands of titles, is The free BARD Mobile app is available available at www.loc.gov/nls. -

Black Panther As Spirit Trip Laurel Zwissler Central Michigan University, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 22 Article 41 Issue 1 April 2018 3-30-2018 Black Panther as Spirit Trip Laurel Zwissler Central Michigan University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Zwissler, Laurel (2018) "Black Panther as Spirit Trip," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 22 : Iss. 1 , Article 41. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol22/iss1/41 This Film Review is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Black Panther as Spirit Trip Abstract This is one of a series of film reviews of Black Panther (2018), directed by Ryan Coogler. This review analyzes engagement with the movie as a religious experience and considers some political implications of both its storyline and reception. In particular, the piece focuses on constructions of race, especially in relationship to Africa and African Americans, as well as practical tensions around commodifying dissent. Keywords Black Panther, Marvel, Race, Superheroes, African-American, Disney, Social Justice, Wakanda, Colonialism, America Author Notes Laurel Zwissler is an assistant professor of Religion at Central Michigan University, USA. Her new book, Religious, Feminist, Activist: Cosmologies of Interconnection (University of Nebraska, Anthropology of North America Series), focuses on global justice activists and investigates contemporary intersections between religion, gender, and social justice politics, relating these to theoretical debates about religion in the public sphere. She is now building on this work with ethnographic research within the North American fair- trade movement, as well as occasional visits with contemporary Witchcraft ommc unities. -

Directory Who Is Who?

COMMUNITY INNOVATION GROUP FOR THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Directory Who150 Organizationsis who? 30 Countries Inspire, connect and move forward Referents of transformation and future Organize Support “(…) the history of the black people is to make possible what seems impossible”. Richard Wright Afroinnova is a Manos Visibles initiative that, with the -erating and changing narratives, building global and support of the Spanish Cooperation Agency, diverse audiences. promotes strategic connections between organiza- (vi) Afro Tourism. Organizations focused on promot- tions and innovative leaders of the African diaspora. ing Afro tourism and space mobility with purpose. We seek to share experiences, build common refer- (vii) Health. Organizations that seek to improve the ents and share similar development models to physical and / or emotional well-being of the Afro-de- evidence the advancement of the afro-descendant scendant. population in the world as an exercise of increasing (viii)Activism and mobilization. Organizations dedi- power. cated to protecting the rights and advances of the Afro-descendant community in the world. Afroinnova sees innovative initiatives by organiza- (ix) Development. Organizations that are responsible tions, leaders of Africa and its diaspora worldwide. for promoting the economic and cultural well-being of Our objective is to break the stereotypes and collec- their communities. tive imaginaries about Afro-descendants, thus (x) Afro-fem. Organizations whose main objective is demonstrating the creative processes, the vindication to defend the rights and interests of afro-descendant of African roots and heritage, and stimulating a women. discourse that associates ethnicity with innovation, development and power. Who is who has been the communication strategy of the program AFROINNOVA (www.manosvisi- bles.org), that has weekly shared profiles of African and afrodescendent organizations. -

Lesson 2 for Grades 3-5 by Linda Dukes LESSON OVERVIEW INTRODUCTION Thoughts to Ponder

Growing Anti-racist UU’s: A Curriculum for Children www.uucharlottesville.org/anti-racist-curriculum/ Identity - Lesson 2 for Grades 3-5 by Linda Dukes LESSON OVERVIEW INTRODUCTION Thoughts to Ponder: Imagine being forced to suppress one such ingredient that you openly acknowledge and value. Imagine, for example, being forced to let go of your religion. For people whose faith is a fundamental part of their lives, such a thought is unfathomable. Yet doing so for race makes no more sense. The comment “I don’t see color; I just see people” carries with it one huge implication: It implies that color is a problem, arguably synonymous with “I can see who you are despite your race.” As evidence, note that the phrase is virtually never applied to White people. In over 40 years of life and nearly 15 years as an anti-racist educator, I have yet to hear a White person say in reference to another White person, “I don’t see your color; I just see you.” In my experience, it is always applied to people of color (nearly always by White people). For the students of color whose race is core to their identities, the comment effectively causes many to feel “invisible.” “Then you don’t see me,” one student of color once responded. - Jon Greenberg, “7 Reasons Why ‘Colorblindness’ Contributes to Racism Instead of Solves It” http://everydayfeminism.com/2015/02/colorblindness-adds- to-racism/ Big Questions: Who am I? What do I want others to recognize in me? What do others want me to recognize in them? This session explores the second Unitarian Universalist Principle. -

Blackness Narratives in Technology, Speculative Fiction, and Digital

Black Cyborgs: Blackness Narratives in Technology, Speculative Fiction, and Digital Cultures A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Caitlin Gunn IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Catherine Squires and Dr. Annie Hill June 2020 © Copyright by Caitlin Gunn 2020 Acknowledgments I would like to express my gratitude to those who have helped shape the growth and development of this project. My advisors, Dr. Catherine Squires and Dr. Annie Hill, have helped me develop as a scholar and a person through this project. I cannot thank them enough for their time and their eyes on my work. I’d like to express my gratitude to my committee members for your support and encouragement: Dr. Jigna Desai, Dr. Duchess Harris, and Dr. Zenzele Isoke. Particular thanks to my interview participants, talented writers who took time to talk to me about their lives, process, and deeply important work: Walidah Imarisha, adrienne maree brown, Brittney Morris, K. Tempest Bradford, and LaShawn Wanak. This would not have been possible without your contributions and time. My family and friends have been endlessly supportive. An incomplete list of those I’d like to thank: my father Paul Gunn, my grandmother Clementine Simpson, and my aunt Linda Welch. Thank you to Andrew Schumacher Bethke, Sarah Clinton- McCausland, Dr. Tia-Simone Gardner, Caty Taborda-Whitt, Dr. Lars Mackenzie, Paula Diamond, Dr. Garrett Hoffman, Dr. Darrah Chavey, and Sally Wiedenbeck. Many thanks to my personal mentors, Dr. Nicole Truesdell, Naomi Scheman, and Dr. Aida Martinez-Freeman. i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my mother: Dr. -

Mcs & Marx: Examining Rap from a Historical Materialistic Approach

MCs & Marx: Examining Rap from a Historical Materialistic Approach Ryan “Mac” Keith McCann Plan II Honors Program & Religious Studies Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin April 29, 2016 _______________________________ Chad Seales, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Religious Studies Supervising Professor 1 Abstract: Author: Ryan “Mac” Keith McCann Title: MCs & Marx: Examining Rap from a Historical Materialistic Approach Supervising Professor: Chad Seales, Ph.D. Hip-Hop culture, and especially the genre of rap music, is too often dismissed and denounced without being properly examined and understood. However, if engaged respectfully and thoughtfully, rap music can help us understand some of the complexities of American culture, especially with regards to race, economics, and consumerist religion. In this thesis, I inspect rap using Karl Marx’s historical materialism. This approach assumes that a society’s economic base, its material conditions, determines its superstructure, like culture, politics, religion, etc. Utilizing this methodological approach, in addition to studying other academic works on hip-hop, I analyzed a variety of rappers and their lyrics. After months of research, I have concluded that hip-hop is largely a reflection of its originators’ economic situations – or, in Marxist terms, hip-hop is a superstructure of its pioneers’ economic base. Because a culture’s values reflect its economic base, I believe that hip-hop and its consumerism have, in a sense, replaced the role of religion as one of the primary ways to present and define oneself. 2 Table of Contents While many of the topics intertwine and overlap, this essay is generally organized in the following order: 1.