Black Panther, Killmonger, and Pan-Africanist African-American Identity 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Cat Chronicles a USDA Licensed Facility for “The Vanishing Breeds of Big Cats”

Non-Profit Org. Turpentine Creek Foundation, Inc. U.S. Postage Paid Spring 2018 239 Turpentine Creek Lane Print Group Inc. Eureka Springs, AR. 72632 BIG CAT CHRONICLES A USDA Licensed Facility for “The Vanishing Breeds of Big Cats” Kenny, the true face Spyke, “I am not a pet, I am not a prop.” of white tiger breeding. [email protected] ||| 479.253.5841 ||| www.turpentinecreek.org youtube.com/TurpentineCreek ||| Find us on Facebook! In Memory 2001-2018of Thor A LetterTanya Smith, from President the & Co-Founder President The hardest thing we have to do at the Refuge is bid farewell to the animals we love. Each of them is an individual who Spring Greetings to all of our friends! What a relief it is to see warmer weather coming our way after such a cold has carved a permanent place in our hearts; having to say a final goodbye brings an incredible sense of grief. What snap. We had our work cut out for us this winter as we fought to keep all of the residents of Turpentine Creek brings us solace is the knowledge that we and our supporters have worked tirelessly to ensure that their remaining Wildlife Refuge nice and warm. Some days were harder than others, but we did it! years were full of joy, good food, play, and an abundance of love. With this thought we look back on how our lion Thor, This past winter I reflected on my experience as the director of a sanctuary. In this role I witness many aspects despite having a very difficult start to life, came to live his remaining years to the very fullest at TCWR- bringing joy of a rescued animal’s life – I see them before being rescued, during the rescue process, and after, and I mourn as and a sense of belonging to those around him. -

Aliens of Marvel Universe

Index DEM's Foreword: 2 GUNA 42 RIGELLIANS 26 AJM’s Foreword: 2 HERMS 42 R'MALK'I 26 TO THE STARS: 4 HIBERS 16 ROCLITES 26 Building a Starship: 5 HORUSIANS 17 R'ZAHNIANS 27 The Milky Way Galaxy: 8 HUJAH 17 SAGITTARIANS 27 The Races of the Milky Way: 9 INTERDITES 17 SARKS 27 The Andromeda Galaxy: 35 JUDANS 17 Saurids 47 Races of the Skrull Empire: 36 KALLUSIANS 39 sidri 47 Races Opposing the Skrulls: 39 KAMADO 18 SIRIANS 27 Neutral/Noncombatant Races: 41 KAWA 42 SIRIS 28 Races from Other Galaxies 45 KLKLX 18 SIRUSITES 28 Reference points on the net 50 KODABAKS 18 SKRULLS 36 AAKON 9 Korbinites 45 SLIGS 28 A'ASKAVARII 9 KOSMOSIANS 18 S'MGGANI 28 ACHERNONIANS 9 KRONANS 19 SNEEPERS 29 A-CHILTARIANS 9 KRYLORIANS 43 SOLONS 29 ALPHA CENTAURIANS 10 KT'KN 19 SSSTH 29 ARCTURANS 10 KYMELLIANS 19 stenth 29 ASTRANS 10 LANDLAKS 20 STONIANS 30 AUTOCRONS 11 LAXIDAZIANS 20 TAURIANS 30 axi-tun 45 LEM 20 technarchy 30 BA-BANI 11 LEVIANS 20 TEKTONS 38 BADOON 11 LUMINA 21 THUVRIANS 31 BETANS 11 MAKLUANS 21 TRIBBITES 31 CENTAURIANS 12 MANDOS 43 tribunals 48 CENTURII 12 MEGANS 21 TSILN 31 CIEGRIMITES 41 MEKKANS 21 tsyrani 48 CHR’YLITES 45 mephitisoids 46 UL'LULA'NS 32 CLAVIANS 12 m'ndavians 22 VEGANS 32 CONTRAXIANS 12 MOBIANS 43 vorms 49 COURGA 13 MORANI 36 VRELLNEXIANS 32 DAKKAMITES 13 MYNDAI 22 WILAMEANIS 40 DEONISTS 13 nanda 22 WOBBS 44 DIRE WRAITHS 39 NYMENIANS 44 XANDARIANS 40 DRUFFS 41 OVOIDS 23 XANTAREANS 33 ELAN 13 PEGASUSIANS 23 XANTHA 33 ENTEMEN 14 PHANTOMS 23 Xartans 49 ERGONS 14 PHERAGOTS 44 XERONIANS 33 FLB'DBI 14 plodex 46 XIXIX 33 FOMALHAUTI 14 POPPUPIANS 24 YIRBEK 38 FONABI 15 PROCYONITES 24 YRDS 49 FORTESQUIANS 15 QUEEGA 36 ZENN-LAVIANS 34 FROMA 15 QUISTS 24 Z'NOX 38 GEGKU 39 QUONS 25 ZN'RX (Snarks) 34 GLX 16 rajaks 47 ZUNDAMITES 34 GRAMOSIANS 16 REPTOIDS 25 Races Reference Table 51 GRUNDS 16 Rhunians 25 Blank Alien Race Sheet 54 1 The Universe of Marvel: Spacecraft and Aliens for the Marvel Super Heroes Game By David Edward Martin & Andrew James McFayden With help by TY_STATES , Aunt P and the crowd from www.classicmarvel.com . -

George Floyd's Death and Impact ABC News

Timeline: George Floyd’s Death and Impact ABC News - June 3rd 2020 May 25th • George Floyd Dies in Police Custody -George Floyd, 46, is arrested shortly after 8 p.m. after allegedly using a fake $20 bill at a local Cup Foods. He dies while in police custody. A disturbing cellphone video later posted to Facebook shows an officer pinning Floyd to the ground with his knee on Floyd’s neck while a handcuffed Floyd repeats “I can’t breathe.” The video goes viral. 26th • Responding Officers are fired as Pro- tests begin in Minneapolis 27th • Protests begin in other cities, including Los Angeles and Memphis 28th • Minnesota Governer Activates the Na- tional Guard 29th • An officer, Derek Chauvin, is arrested and charged with third degree murder June in Floyd’s death 1st • Results of an independent autopsy find that Floyd’s death was due to asphyx- iation - this runs contrary to the police autopsy, which said the death was due to underlying health conditions Floyd had • A Civil Rights Charge is filed against 2nd Minneapolis Police • three more officers are charged for 3rd aiding and abetting second degree murder. Chauvin’s charge is adjusted to second de- gree murder What’s next? Demonstrators continue to bat- tle white supremacy and police brutality. Groups call to defund, divest, and abolish po- lice across the U.S. and abroad. Abolitionists continue to call for the Abolition of prisons. Why The Small Protests In Small Towns Across America Matter by Anne Petersen Dorian Miles arrived in Havre, Montana — a windy farm town, population 9,700, along what’s known as Montana’s Hi-Line — just five months ago, a young man from Georgia coming to play football for Montana State University–Northern. -

Fantastic Four Compendium

MA4 6889 Advanced Game Official Accessory The FANTASTIC FOUR™ Compendium by David E. Martin All Marvel characters and the distinctive likenesses thereof The names of characters used herein are fictitious and do are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. not refer to any person living or dead. Any descriptions MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS including similarities to persons living or dead are merely co- are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. incidental. PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION and the ©Copyright 1987 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Game Design Rights Reserved. Printed in USA. PDF version 1.0, 2000. ©1987 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 A Brief History of the FANTASTIC FOUR . 2 The Fantastic Four . 3 Friends of the FF. 11 Races and Organizations . 25 Fiends and Foes . 38 Travel Guide . 76 Vehicles . 93 “From The Beginning Comes the End!” — A Fantastic Four Adventure . 96 Index. 102 This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc., and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. All characters appearing in this gamebook and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. -

Dismantling Racism Task Force

CHRIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH Dismantling Racism Task Force Resource Materials 10/25/2020 The Dismantling Racism Task Force has compiled a list of recommended educational materials in the form of books, film, videos, podcasts, et.al. These materials are categorized based on their subject matter using a legend of color-coded, geometric icons which is included with this collection. For convenience, a terminology section is also included. History, despite its wrenching pain, Cannot be unlived, and if faced with courage, Need not be lived again. - Maya Angelou, “On the Pulse of Morning” 1 Books Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents Author: Isabel Wilkerson (2020) 388 pages (469 pages with notes, etc.) Brilliant, revealing, and impressively-researched, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents is an eye-opening story of people and history and how lives and behaviors are influenced by the rigid hierarchy of caste. Pulitzer Prize winning author, instructor and lecturer Isabel Wilkerson uses the stories of real people to show how America throughout its history, and still today, has been shaped by a hidden caste system. This rigid hierarchy of human rankings not only influences people’s lives but the nation’s fate. She shows us that racism, which resides within the invisible caste structure in America, is so ingrained that it is autonomic in expression and mostly goes unnoticed or unchallenged. Gifted with great narrative and literary power, Isabel Wilkerson offers a new perspective on American history while linking and illustrating the caste systems of America, India and Nazi Germany. That Germany used America as a model for its treatment of Jewish people is chilling. -

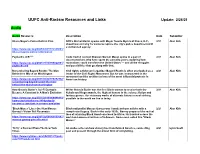

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21

UUFC Anti-Racism Resources and Links Update: 2/28/21 Audio Audio Resource Description Date Submitter Ithaca Mayor's Police Reform Plan NPR's Michel Martin speaks with Mayor Svante Myrick of Ithaca, N.Y., 2/21 Alan Kirk about how and why he wants to replace the city's police department with a civilian-led agency. https://www.npr.org/2021/02/27/972145001/ ithaca-mayors-police-reform-plan Payback's A B**** Code Switch co-host Shereen Marisol Meraji spoke to a pair of 2/21 Alan Kirk documentarians who have spent the past two years exploring how https://www.npr.org/2021/01/14/956822681/ reparations could transform the United States — and all the struggles paybacks-a-b and possibilities that go along with that. Remembering Bayard Rustin: The Man Civil rights activist and organizer Bayard Rustin is often overlooked as a 2/21 Alan Kirk Behind the March on Washington leader of the Civil Rights Movement. But he was instrumental in the movement and the architect of one of the most influential protests in https://www.npr.org/2021/02/22/970292302/ American history. remembering-bayard-rustin-the-man- behind-the-march-on-washington How Octavia Butler's Sci-Fi Dystopia Writer Octavia Butler was the first Black woman to receive both the 2/21 Alan Kirk Became A Constant In A Man's Evolution Nebula and Hugo awards, the highest honors in the science fiction and fantasy genres. Her visionary works of alternate futures reveal striking https://www.npr.org/2021/02/16/968498810/ parallels to the world we live in today. -

Vision Vol. 1: Little Worse Than a Man Kindle

VISION VOL. 1: LITTLE WORSE THAN A MAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tom King,Gabriel Hernandez Walta | 136 pages | 28 Jul 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785196570 | English | New York, United States Vision Vol. 1: Little Worse Than A Man PDF Book Personaje de Marvel Comics. All the pressure of having a family on present here and then some. The books are also available in paperback, but given their inseparability and being the same combined price as the hardcover, you should really get that instead. Vision and his family are synthezoids but Vision, in this series, seems to desperately want acceptance among humans as one of them, despite the impossibility of ever being human. Comic superstar-in-the-making Tom King teams with talented artist Gabriel H. Well, he decided to create himself a happy family, and it's gone very, very wrong. Also, one who is very powerful, but also deeply misunderstood. Iron Man The Mighty Avengers. The story has a narrative by a mysterious person. Return to Book Page. And in addition, can a family survive if its members are building their relationships on a series of lies? Walta and fan-favourite colourist J I don't usually review any of the series I follow in single issues until they're released in trade, but I'm making an exception for The Vision as it's one of the best comic books I've ever read. At which point does our mind string together meaningless letters to create in our minds a word to which we as a society have assigned a meaning to, decided upon, and then stifled individuality out of? Clayton Cowles Letterer ,. -

Black Panther

MOVIE DISCUSSION GUIDE Black Panther The first Marvel movie to have a black director, a black lead actor and a majority black supporting cast, “Black Panther” made history for more than just its record-breaking box office numbers. The complex characters and strong storyline marks the first time many demographics were able to see themselves on the big screen in a big way. Use this powerful film to discuss race, power and gender roles with your audiences. Plot Summary: “Black Panther” follows T’Challa who, after the events of “Captain America: Civil War,” returns home to the isolated, technologically advanced African nation of Wakanda to take his place as King. However, when an old enemy reappears on the radar, T’Challa’s mettle as King and Black Panther is tested when he is drawn into a conflict that puts the entire fate of Wakanda and the world at risk. © 2019 Marvel Programming Suggestions This discussion guide is designed to facilitate educational programs after viewing the film “Black Panther.” Its purpose is to generate discussion based on social issues found within the movie and for program participants to reflect on themes that might be pertinent to them. Therefore, there are no “right” or “wrong” Issues answers to questions in this guide. The discussion facilitator may choose to utilize one of the following Black History activities as a means of developing discussion: Gender Roles • Teach patrons about the “real” Wakanda – Africa. Invite an International Studies professor to come provide a mini refresher course on Africa’s Diversity/ history and current affairs before the film, including the lasting effects of Multiculturalism colonialism in Africa, the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade and more. -

Understanding the Roles of Vision in the Control of Human Locomotion

Gait & Posture 5 (1997) 54-69 Review article Understanding the roles of vision in the control of human locomotion Aftab E. Patla* Neural Conrrol Lab. Department cf Kimsiology, Uniwrsit~~ of Waterloo, Waterloo. Ont. N2L Xl, Carmln Accepted 31 October 1996 Abstract This review focuses on advances in our understanding of the roles played by vision in the control of human locomotion. Vision is unique in its ability to provide information about near and far environment almost instantaneously: this information is used to regulate locomotion on a local level (step by step basis) and a global level (route planning). Basic anatomy and neurophysiology of the sensory apparatus. the neural substrate involved in processing this visual input, descending pathways involved in effecting control and mechanisms for controlling gaze are discussed. Characteristics of visual perception subserving control of locomotion include the following: (a) intermittent visual sampling is adequate for safe travel over various terrains; (b) information about body posture and movement from the visual system is given higher priority over information from the other two sensory modalities; (c) exteroceptive information about the environment is used primarily in a feedforward sampled control mode rather than on-line control mode; (d) knowledge acquired through past experience influences the interpretation of the exteroceptive information; (e) exproprioceptive information about limb position and movement is used on-line to fine tune the swing limb trajectory; (f) exproprioceptive -

Ecology and Evolution of Melanism in Big Cats

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.69558 Provisional chapter Chapter 6 Ecology and Evolution of Melanism in Big Cats: Case EcologyStudy with and Black Evolution Leopards of Melanism and Jaguars in Big Cats: Case Study with Black Leopards and Jaguars Lucas Gonçalves da Silva Lucas Gonçalves da Silva Additional information is available at the end of the chapter Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.69558 Abstract Variations in animal coloration have intrigued evolutionary biologists for a long time. Among the observed pigmentation polymorphisms, melanism has been reported in multiple organisms (influencing several biological factors), and classical hypothesis has suggested that such variant can present adaptive advantages under certain ecological conditions. In leopards (Panthera pardus) and jaguars (Panthera onca), melanism is caused by recessive and dominant mutations in the ASIP and MC1R genes, respectively. This chapter is focused on melanism in these two species, aiming to analyze its geographic pattern. About 623 leopard and 980 jaguar records that were used as baseline for model- ing and statistical analyses were obtained. The frequency of melanism was 10% for both species. In leopards, melanism was present in five subspecies and strongly associated with moist forests, especially in Southeast Asia. In jaguars, melanism was totally absent from open and periodically flooded landscapes; in contrast, forests displayed a frequency that was similar to the expectations. The analyses of the environmental predictors sug- gest a relevant role for factors such as moisture and temperature. These observations sup- port the hypothesis that melanism in big cats is not a neutral polymorphism (influenced by natural selection), leading to a nonrandom geographic distribution of this coloration phenotype. -

Test 29 HISTORY FULL SYLLABUS

IASbaba’s 60 DAY PLAN 2021 UPSC HISTORY [DAY 3] 2021 Q.1) Consider the following statements with reference to the Charter Act of 1813: 1. Continental system by Napoleon, by which the European ports were closed for Britain, was one of the reasons for bringing or introducing this Act. 2. Christian missionaries were permitted to come to India and preach their religion. 3. The regulations made by the Councils of Madras, Bombay and Calcutta were now required to be laid before the British Parliament. Which of the following statements is/are correct? a) 2 and 3 only b) 1 and 2 only c) 1 and 3 only d) 1, 2 and 3 Q.1) Solution (d) Explanation The Charter Act of 1813: Why this Act was brought? In England, the business interests were pressing for an end to the Company’s monopoly over trade in India because of a spirit of laissez-faire and the continental system by Napoleon by which the European ports were closed for Britain. Provisions of the Act The Company’s monopoly over trade in India ended, but the Company retained the trade with China and the trade in tea. The Company’s shareholders were given a 10.5 per cent dividend on the revenue of India. The regulations made by the Councils of Madras, Bombay and Calcutta were now required to be laid before the British Parliament. The Company was to retain the possession of territories and the revenue for 20 years more, without prejudice to the sovereignty of the Crown. Powers of the Board of Control were further enlarged. -

September 2016 Dear Freedom of Information Request Reference No

Norfolk Constabulary Freedom of Information Department Jubilee House Falconers Chase Wymondham Norfolk NR18 0WW September 2016 Tel: 01953 425699 Ext: 2803 Email: [email protected] Dear Freedom of Information Request Reference No: FOI 002950/16 I write in connection with your request for information received by the Norfolk Constabulary on the 4th August 2016 in which you sought access to the following information: Please could you inform me of the following. How many sightings of big cats have been reported to your force during the previous six calendar years. These years are: 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Norfolk Constabulary holds information relevant to your request. Response to your Request Norfolk Constabulary has located the following information as relevant to your request. The Joint Performance and Analysis Department has undertaken research of incidents reported to the Constabulary using the following keywords:- Big cat Leopard Lynx Lion Tiger Panther Jaguar Cougar Puma Incidents that are not relevant to your request have been removed, for example those referring to a Jaguar type car, etc. Date Location Details 15/03/2010 Norwich Dog attacked by large black cat like animal 15/05/2010 Bradwell Very large striped cat sitting in road, looks like a tiger (Toy) Report of possible attack by a ‘big cat’. Labrador sized, black, 05/07/2010 Downham Market made wheezing/growling sound. Reports a very large cat – 3’ tall, 3-4’ tail, black, carrying a hare in 23/07/2010 Coltishall its mouth. May be a puma 24/07/2010 Coltishall Saw a black puma, watched it for 30 mins Saw a cat bigger than a dog with really long tail, feel it was a 25/07/2010 Hopton panther, black.