Asplenium Bradleyi) D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Revised February 24, 2017 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Guidance Document Pohakuloa Training Area Plant Guide

GUIDANCE DOCUMENT Recovery of Native Plant Communities and Ecological Processes Following Removal of Non-native, Invasive Ungulates from Pacific Island Forests Pohakuloa Training Area Plant Guide SERDP Project RC-2433 JULY 2018 Creighton Litton Rebecca Cole University of Hawaii at Manoa Distribution Statement A Page Intentionally Left Blank This report was prepared under contract to the Department of Defense Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP). The publication of this report does not indicate endorsement by the Department of Defense, nor should the contents be construed as reflecting the official policy or position of the Department of Defense. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the Department of Defense. Page Intentionally Left Blank 47 Page Intentionally Left Blank 1. Ferns & Fern Allies Order: Polypodiales Family: Aspleniaceae (Spleenworts) Asplenium peruvianum var. insulare – fragile fern (Endangered) Delicate ENDEMIC plants usually growing in cracks or caves; largest pinnae usually <6mm long, tips blunt, uniform in shape, shallowly lobed, 2-5 lobes on acroscopic side. Fewer than 5 sori per pinna. Fronds with distal stipes, proximal rachises ocassionally proliferous . d b a Asplenium trichomanes subsp. densum – ‘oāli’i; maidenhair spleenwort Plants small, commonly growing in full sunlight. Rhizomes short, erect, retaining many dark brown, shiny old stipe bases.. Stipes wiry, dark brown – black, up to 10cm, shiny, glabrous, adaxial surface flat, with 2 greenish ridges on either side. Pinnae 15-45 pairs, almost sessile, alternate, ovate to round, basal pinnae smaller and more widely spaced. -

Spring 2015 (23:1) (PDF)

Contents NATIVE NOTES Page Field Trip announcements 1-2 Walnut Twig Beetle 3 Viburnum leaf Beetle Ferns and Workshop 4-5 Kate’s Mountain Clover* This and That 6 WEST VIRGINIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY NEWSLETTER News of WVNPS 7 Events, Resources VOLUME 23:1 SPRING 2015 Dues Form 8 Judy Dumke-Editor: [email protected] Phone 740-894-6859 e e e visit us at www.wvnps.org e e e . Field Trip McDowell County Panther Wildlife Management Area April 24-26 The West Virginia Native Plant Society will conduct a field trip to Panther Wildlife Management Area, in McDowell County. The area consists of a very old second growth hardwood forest dominated with hemlock. Spring wildflowers such as Fern-Leaf Phacelia, Large Yellow Lady’s Slipper, Long-Flowered Alumroot, Showy Orchis, Mandarin, Galax, Whorled Pogonia, and Recurved Fetterbush should be near their peak in this southern tip of West Virginia. A board meeting will be held at the Group Camp Recurved fetterbush © Kevin Campbell Lodge on 4/25/2015 from 6:00 to 8:00 pm. Location: Panther is located in the rugged mountains near the southern border of West Virginia, Virginia, and Kentucky. From Route 52, one mile north of Iaegar, turn at the sign to Panther. At the Panther Post Office, turn left at the sign and follow the road approximately 3.5 miles to the area entrance. The Group Camp Lodge is approximately two miles south of the entrance on the right. Lodging: Group Camp Lodge. Large bunk area for $20.00 for one night or $30.00 for two nights payable to Judi White, © Kevin Campbell photo WVNPS Treasurer, 148 Wellesley Dr., Washington, WV 26181. -

Ferns Robert H

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Illustrated Flora of Illinois Southern Illinois University Press 10-1999 Ferns Robert H. Mohlenbrock Southern Illinois University Carbondale Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/siupress_flora_of_illinois Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Mohlenbrock, Robert H., "Ferns" (1999). Illustrated Flora of Illinois. 3. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/siupress_flora_of_illinois/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Southern Illinois University Press at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illustrated Flora of Illinois by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF ILLINOIS ROBERT H. MOHLENBROCK, General Editor THE ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF ILLINOIS s Second Edition Robert H. Mohlenbrock SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY PRESS Carbondale and Edwardsville COPYRIGHT© 1967 by Southern Illinois University Press SECOND EDITION COPYRIGHT © 1999 by the Board of Trustees, Southern Illinois University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 02 01 00 99 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mohlenbrock, Robert H., 1931- Ferns I Robert H. Mohlenbrock. - 2nd ed. p. em.- (The illustrated flora of Illinois) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Ferns-Illinois-Identification. 2. Ferns-Illinois-Pictorial works. 3. Ferns-Illinois-Geographical distribution-Maps. 4. Botanical illustration. I. Title. II. Series. QK525.5.I4M6 1999 587'.3'09773-dc21 99-17308 ISBN 0-8093-2255-2 (cloth: alk. paper) CIP The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.§ This book is dedicated to Miss E. -

Mississippi Natural Heritage Program Special Plants - Tracking List -2018

MISSISSIPPI NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM SPECIAL PLANTS - TRACKING LIST -2018- Approximately 3300 species of vascular plants (fern, gymnosperms, and angiosperms), and numerous non-vascular plants may be found in Mississippi. Many of these are quite common. Some, however, are known or suspected to occur in low numbers; these are designated as species of special concern, and are listed below. There are 495 special concern plants, which include 4 non- vascular plants, 28 ferns and fern allies, 4 gymnosperms, and 459 angiosperms 244 dicots and 215 monocots. An additional 100 species are designated “watch” status (see “Special Plants - Watch List”) with the potential of becoming species of special concern and include 2 fern and fern allies, 54 dicots and 44 monocots. This list is designated for the primary purposes of : 1) in environmental assessments, “flagging” of sensitive species that may be negatively affected by proposed actions; 2) determination of protection priorities of natural areas that contain such species; and 3) determination of priorities of inventory and protection for these plants, including the proposed listing of species for federal protection. GLOBAL STATE FEDERAL SPECIES NAME COMMON NAME RANK RANK STATUS BRYOPSIDA Callicladium haldanianum Callicladium Moss G5 SNR Leptobryum pyriforme Leptobryum Moss G5 SNR Rhodobryum roseum Rose Moss G5 S1? Trachyxiphium heteroicum Trachyxiphium Moss G2? S1? EQUISETOPSIDA Equisetum arvense Field Horsetail G5 S1S2 FILICOPSIDA Adiantum capillus-veneris Southern Maidenhair-fern G5 S2 Asplenium -

Oakes and Camptosorus Rhizophyllus

A STUDY OF As?lenium platyneuron (L.) Oakes AND Camptosorus rhizophyllus (L.) Link \-l1TH AN .SllPH..t::..2IS em SPOiC:': 10Rl.~HOLOGY A Senior Paper Submitted to Or. J. C. r.falayer of Ball State University by Lois A. I(inder In Partial Fulfillment of the Requiren.ents for graduation on The Honors Program l'.J:ay I, 1966 :;;rCo~1 7he:! ii ":'"\ J-i-t.:., (.~1 ~ ' ..... -, ~--~ ~: i,~ , '")6 t, ,k ,~-r;0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ••••••••••.••••.••••••••••••••.••..• iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. .. .. .. .. iv INTRODUCTION •••••••••••••••• .. .. .. 1 REVIE\~ OF irH~~ LI Ir .2.PJ.l.TUl<'E •••••••••••••••••••••••••• 2 Morphology ••••.•••••..•••••••••••••••••••••••••• 2 Taxonomic Realtionships •• ••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 NETrIODS MATERlii.LS •• .. .. .. .. .. 6 General 1>1orphology •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 6 :-")pore }forphology •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 7 '[lATA ••••••••••••••••• . .. 15 General Horphology.............................. 15 Spore Morphology................................ 30 DISCUSSION. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 39 sm~J~y........................................... 46 BIBLIOGRAPHY...................................... 47 iii LIST OF TABLES Page Table I. Gross morphological calculations of Gamptosorus rhizophyllus (L.) Link I. A Specimen measurements ••••••••••••••••• 8 I. B Leaf height analysis •••••••••••••••••• 19 II. Gross morphological calculations of iisplenium platyneuron (L.) C.akes II. A Specimen measurements................. 9 II. B Leaf height analysis ••••••••••••••••• 24 III. :}ross morphological -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

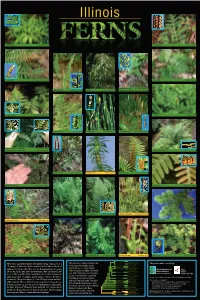

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

Asplenium Rhizophyllum L

Asplenium rhizophyllum L. walking fern Photos by Michael R. Penskar State Distribution Best Survey Period Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Status: State threatened Niagara Escarpment. Elsewhere, this species occurs locally on alkaline bedrock outcrops in Dickinson, Global and state rank: G5/S2S3 Schoolcraft, and Houghton counties, with additional Family: Aspleniaceae (spleenwort family) local populations found in the Lower Peninsula on South Manitou Island (Leleenau County). It is also Synonyms: Camptosorus rhizophyllus (L.) Link known from a sinkhole in Alpena County, and from an unusual occurrence in Berrien County where a small Taxonomy: This very distinctive species has been but vigorous colony was discovered on a limestone segregated by several authors and placed in the genus boulder along a stream. Camptosorus (Morin et al. 1993), a name under which it is known in many manuals and other publications. It Recognition: Asplenium rhizophyllum is an extremely forms part of a complex of Appalachian spleenworts distinctive fern, characterized by its tendency to form researched by Wagner (1954) in a well-known study of dense colonies by reproducing via tip-rooting on hybridization and backcrossing. moss-covered dolomite boulders and other types of rock outcrops. Individual plants consist of clumps of Total range: Walking fern occurs in eastern North fronds (leaves) arising from short, scaly rhizomes. The America, ranging from southern Ontario and Quebec small, 1-3 cm wide fronds, which have net-like (reticu- in Canada south to Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, late) veins and may range up to ca. 30 cm in length, occurring west to Wisconsin, Iowa, Kansas, and are stalked, and have slender, long-tapering, lance- Oklahoma. -

A List of the Ferns of Mahoning County with Special Reference to Mill Creek Park

86 The Ohio Naturalist. [Vol. X, No. 4, A LIST OF THE FERNS OF MAHONING COUNTY WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO MILL CREEK PARK. EARNEST W. VICKERS. Lying toward the north-eastern corner of the state and belonging to a group known as the Highland Counties of Ohio, Mahoning presents variations of soil and surface which find natural expression in its flora. The erosions of the Mahoning River which flows up the west side of the County and again down across the north-east corner, as well as numerous smaller streams have left steep banks, glens, ledges and cliffs and in the case of Mill Creek—which gives the park its name—at Lautermain Falls, near Youngstown, a gorge has been cut seventy-three feet in depth. It is in these places that the rock loving ferns find congenial habitat. There are rich wet woods—remnants of noble forests— where the sylvan groups are well represented; while swamps of greater or less area are scattered over the county where ferns of the marsh or bog flourish. In its remarkably varied character in such small compass, Mill Creek Park represents the whole county so faithfully that the botanist may expect, and without disappointment, to find therein almost a complete living index to the fern flora of Mahoning County. The ferns listed below have been verified by Prof. J. H. Schaffner and are represented by specimens deposited in the State Herbarium at Columbus, Ohio. Polypodium vulgare L. Common Polypody. Commonest on rocks and ledges, its natural home, but also found on stumps and logs. -

100 Years of Change in the Flora of the Carolinas

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, Georgia, and surrounding areas Working Draft of 11 January 2007 by Alan S. Weakley University of North Carolina Herbarium (NCU) North Carolina Botanical Garden University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Campus Box 3280 Chapel Hill NC 27599-3280 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents THE FLORA .................................................................................................................................................................................................................6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................................................................................................9 FERNS AND “FERN ALLIES”............................................................................................................................................................................10 ASPLENIACEAE Frank 1877 (Spleenwort Family) ........................................................................................................................................17 AZOLLACEAE Wettstein 1903 (Mosquito Fern Family) .................................................................................................................................20 BLECHNACEAE (C. Presl) Copeland 1947 (Deer Fern Family) ...................................................................................................................21 DENNSTAEDTIACEAE Pichi Sermolli 1970 (Bracken Family) ....................................................................................................................22 -

Journal the New York Botanical Garden

VOL. XXXV SEPTEMBER, 1934 No. 417 JOURNAL OF THE NEW YORK BOTANICAL GARDEN FERNS WITHIN ONE HUNDRED MILES OF NEW YORK CITY JOHN K. SMALL TRIFOLIUM VIRGINICUM IN CULTIVATION T. H. EVERETT THE ELIZABETH GERTRUDE BRITTON MOSS HERBARIUM IS ESTABLISHED E. D. MERRILL SCIENCE COURSE FOR PROFESSIONAL GARDENERS ENTERS THIRD YEAR PUBLIC LECTURES SCHEDULED FOR SEPTEMBER, OCTOBER, AND NOVEMBER A GLANCE AT CURRENT LITERATURE CAROL H. WOODWARD NOTES, NEWS, AND COMMENT PUBLISHED FOR THE GARDEN AT LIME AND GREEN STREETS, LANCASTER, PA. THE SCIENCE PRESS PRINTING COMPANY Entered at the post-office in Lancaster, Pa., as second-class matter. Annual subscription $1.00 Single copies 10 cents Free to members of the Garden THE NEW YORK BOTANICAL GARDEN BOARD OF MANAGERS I. ELECTIVE MANAGERS Until 1935: L. H. BAILEY, THOMAS J. DOLEN, MARSHALL FIELD, MRS. ELON HUNTINGTON HOOKER, KENNETH K. MACKENZIE, JOHN L. MERRILL (Vice-presi dent and Treasurer), and H. HOBART PORTER. Until 1936: ARTHUR M. ANDERSON, HENRY W. DE FOREST (President), CLARENCE LEWIS, E. D. MERRILL (Director and Secretary), HENRY DE LA MON TAGNE, JR. (Assistant Treasurer & Business Manager), and LEWIS RUTHER- FURD MORRIS. Until 1937: HENRY DE FOREST BALDWIN (Vice-president), GEORGE S. BREWSTER, CHILDS FRICK, ADOLPH LEWISOHN, HENRY LOCKHART, JR., D. T. MACDOUGAL, and JOSEPH R. SWAN. II. EX-OFFICIO MANAGERS FIORELLO H. LAGUARDIA, Mayor of the City of New York. ROBERT MOSES, Park Commissioner. GEORGE J. RYAN, President of the Board of Education. III. APPOINTIVE MANAGERS A. F. BLAKESLEE, appointed by the Torrey Botanical Club. R. A. HARPER, SAM F. TRELEASE, EDMUND W. SINNOTT, and MARSTON T.