Aspleniaceae) in a Brazilian Atlantic Forest Fragment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2015 (23:1) (PDF)

Contents NATIVE NOTES Page Field Trip announcements 1-2 Walnut Twig Beetle 3 Viburnum leaf Beetle Ferns and Workshop 4-5 Kate’s Mountain Clover* This and That 6 WEST VIRGINIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY NEWSLETTER News of WVNPS 7 Events, Resources VOLUME 23:1 SPRING 2015 Dues Form 8 Judy Dumke-Editor: [email protected] Phone 740-894-6859 e e e visit us at www.wvnps.org e e e . Field Trip McDowell County Panther Wildlife Management Area April 24-26 The West Virginia Native Plant Society will conduct a field trip to Panther Wildlife Management Area, in McDowell County. The area consists of a very old second growth hardwood forest dominated with hemlock. Spring wildflowers such as Fern-Leaf Phacelia, Large Yellow Lady’s Slipper, Long-Flowered Alumroot, Showy Orchis, Mandarin, Galax, Whorled Pogonia, and Recurved Fetterbush should be near their peak in this southern tip of West Virginia. A board meeting will be held at the Group Camp Recurved fetterbush © Kevin Campbell Lodge on 4/25/2015 from 6:00 to 8:00 pm. Location: Panther is located in the rugged mountains near the southern border of West Virginia, Virginia, and Kentucky. From Route 52, one mile north of Iaegar, turn at the sign to Panther. At the Panther Post Office, turn left at the sign and follow the road approximately 3.5 miles to the area entrance. The Group Camp Lodge is approximately two miles south of the entrance on the right. Lodging: Group Camp Lodge. Large bunk area for $20.00 for one night or $30.00 for two nights payable to Judi White, © Kevin Campbell photo WVNPS Treasurer, 148 Wellesley Dr., Washington, WV 26181. -

Ferns Robert H

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Illustrated Flora of Illinois Southern Illinois University Press 10-1999 Ferns Robert H. Mohlenbrock Southern Illinois University Carbondale Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/siupress_flora_of_illinois Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Mohlenbrock, Robert H., "Ferns" (1999). Illustrated Flora of Illinois. 3. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/siupress_flora_of_illinois/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Southern Illinois University Press at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illustrated Flora of Illinois by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF ILLINOIS ROBERT H. MOHLENBROCK, General Editor THE ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF ILLINOIS s Second Edition Robert H. Mohlenbrock SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY PRESS Carbondale and Edwardsville COPYRIGHT© 1967 by Southern Illinois University Press SECOND EDITION COPYRIGHT © 1999 by the Board of Trustees, Southern Illinois University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 02 01 00 99 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mohlenbrock, Robert H., 1931- Ferns I Robert H. Mohlenbrock. - 2nd ed. p. em.- (The illustrated flora of Illinois) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Ferns-Illinois-Identification. 2. Ferns-Illinois-Pictorial works. 3. Ferns-Illinois-Geographical distribution-Maps. 4. Botanical illustration. I. Title. II. Series. QK525.5.I4M6 1999 587'.3'09773-dc21 99-17308 ISBN 0-8093-2255-2 (cloth: alk. paper) CIP The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.§ This book is dedicated to Miss E. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

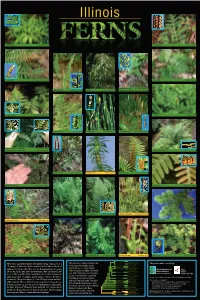

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

A Revised Family-Level Classification for Eupolypod II Ferns (Polypodiidae: Polypodiales)

TAXON 61 (3) • June 2012: 515–533 Rothfels & al. • Eupolypod II classification A revised family-level classification for eupolypod II ferns (Polypodiidae: Polypodiales) Carl J. Rothfels,1 Michael A. Sundue,2 Li-Yaung Kuo,3 Anders Larsson,4 Masahiro Kato,5 Eric Schuettpelz6 & Kathleen M. Pryer1 1 Department of Biology, Duke University, Box 90338, Durham, North Carolina 27708, U.S.A. 2 The Pringle Herbarium, Department of Plant Biology, University of Vermont, 27 Colchester Ave., Burlington, Vermont 05405, U.S.A. 3 Institute of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, National Taiwan University, No. 1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Road, Taipei, 10617, Taiwan 4 Systematic Biology, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Norbyv. 18D, 752 36, Uppsala, Sweden 5 Department of Botany, National Museum of Nature and Science, Tsukuba 305-0005, Japan 6 Department of Biology and Marine Biology, University of North Carolina Wilmington, 601 South College Road, Wilmington, North Carolina 28403, U.S.A. Carl J. Rothfels and Michael A. Sundue contributed equally to this work. Author for correspondence: Carl J. Rothfels, [email protected] Abstract We present a family-level classification for the eupolypod II clade of leptosporangiate ferns, one of the two major lineages within the Eupolypods, and one of the few parts of the fern tree of life where family-level relationships were not well understood at the time of publication of the 2006 fern classification by Smith & al. Comprising over 2500 species, the composition and particularly the relationships among the major clades of this group have historically been contentious and defied phylogenetic resolution until very recently. Our classification reflects the most current available data, largely derived from published molecular phylogenetic studies. -

New and Noteworthy Additions to the Arkansas Fern Flora

Peck, J.H. 2011. New and noteworthy additions to the Arkansas fern flora. Phytoneuron 2011-30: 1–33. NEW AND NOTEWORTHY ADDITIONS TO THE ARKANSAS FERN FLORA JAMES H. PECK Department Biology University of Arkansas at Little Rock 2801 S. University Ave. Little Rock, AR 72204 [email protected] ABSTRACT Since 1995, 11 fern taxa have been added to the Arkansas flora as new and native, including Asplenium montanum , A. ruta-muraria , A. septentrianale , A. ×trudellii , Athyrium angustum , Azolla caroliniana , Dryopteris goldiana , D. celsa × goldiana , Marsilea macropoda , Palhinhaea cernua , and Trichomanes intracatum . Of the reported Arkansas native ferns, one was deleted (Azolla caroliniana ), being subsumed by Azolla mexicana and now correctly known as Azolla microphylla . Since 1995, 20 fern taxa have been added to the Arkansas fern flora as new and naturalized, including Arachnioides simplicior , Athyrium nipponicum ‘Pictum’, Cyrtomium falcatum , C. fortunei , Dryopteris erythrospora , Hypolepis tenuifolia , Marsilea mutica , M. quadrifolia , Matteuccia struthiopteris , Nephrolepis exaltata , Polystichum tsus-sinense , Phegopteris decursive-pinnata , Salvinia minima , S. molesta , Selaginella braunii , S. kraussiana , S. k. ‘Aurea’, S. k. ‘Brownii’, S. k. ‘Goldtips’, and S. uncinata . Of the reported Arkansas naturalized ferns, one was deleted (C. fortunei ), being without a known voucher. There are now 97 native and 24 naturalized fern taxa known and documented in the Arkansas fern flora. The total Arkansas fern flora is now 121 taxa documented with 3019 county-level occurrence records. Noteworthy update records and comments are reported for 79 of 97 Arkansas native species and 25 Arkansas naturalized species. KEY WORDS : Arkansas, ferns, county distribution Over the last 30 years, studies have been conducted to document the diversity and abundance of the Arkansas fern [pteridophyte] flora. -

Asplenium Platyneuron, a New Pteridophyte for Europe

Preslia 82: 357–364, 2010 357 Asplenium platyneuron, a new pteridophyte for Europe Asplenium platyneuron (Aspleniaceae, Pteridophyta), druh nově zaznamenaný v Evropě Libor E k r t1 & Richard H r i v n á k2 1Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Branišovská 31, CZ-370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic, email: [email protected]; 2Institute of Botany, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Dúbravská cesta 9, SK-845 23 Bratislava, Slovakia Ekrt L. & Hrivnák R. (2010): Asplenium platyneuron, a new pteridophyte for Europe. – Preslia 82: 357–364. Eleven plants of Asplenium platyneuron (ebony spleenwort) were found in disturbed serpentine woodland in south-central Slovakia (Central Europe). This find represents a new addition to the fern flora of Europe. It is probably the result of long-distance spore dispersal. The nearest known sites for this species are those in eastern North America, about 6500 km away. The important determina- tion characters of A. platyneuron are described, the Slovakian locality characterized and an over- view of the ecology and a map of the worldwide distribution of this species provided. K e y w o r d s: alien species, Appalachian Asplenium complex, Central Europe, ferns, long distance dispersal, serpentines, Slovakia Introduction Ferns and lycophytes are capable of dispersing over long distances by wind-blown spores, as evidenced by the facts that they are common elements of the floras of isolated oceanic islands and are often among the first colonizers of open and newly available habitats. The extent to which species are effective dispersers depends on a wide range of factors such as life-history, adaptive, genetic characteristics and their interplay with the biotic and physi- cal environments (Tryon 1970, Smith 1972, Moran & Smith 2001, Perrie & Brownsey 2007, Ranker & Geiger 2008). -

Yatabe Et Al., 2009

Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society,2009,160,42–63.With10figures Patterns of hybrid formation among cryptic species of bird-nest fern, Asplenium nidus complex (Aspleniaceae), in West Malesia YOKO YATABE1*, WATARU SHINOHARA2, SADAMU MATSUMOTO1 and NORIAKI MURAKAMI3 1Department of Botany, National Museum of Nature and Science, Amakubo, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-0005, Japan 2Department of Botany, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8224, Japan 3Makino Herbarium, Tokyo Metropolitan University, Hachioji, Tokyo 192-0397, Japan Received 7 August 2008; accepted for publication 5 March 2009 In order to clarify patterns of hybrid formation in the Asplenium nidus complex, artificial crossing experiments were performed between individuals of genetically differentiated groups based on the sequence of the rbcL gene, including A. australasicum from New Caledonia, A. setoi from Japan and several cryptic species in the A. nidus complex. No hybrid plants were obtained in crosses between nine of the 16 pairs. Even for pairs that generated hybrids, the frequency of hybrid formation was lower than expected given random mating, or only one group was able to act as the maternal parent, when the genetic distance (Kimura’s two parameter) between parental individuals was at least 0.006. Sterile hybrids were produced by three pairs that were distantly related but capable of forming hybrids. Considering the results of the crosses together with the genetic distance between the parental individuals, it seems that the frequency of hybrid formation decreases rapidly with increasing divergence. The frequency of hybrid formation has not been previously examined in homosporous ferns, but it seems that a low frequency of hybrid formation can function as an important mechanism of reproductive isolation between closely related pairs of species in the A. -

TAXON:Asplenium Antiquum Makino SCORE:1.0 RATING:Low Risk

TAXON: Asplenium antiquum SCORE: 1.0 RATING: Low Risk Makino Taxon: Asplenium antiquum Makino Family: Aspleniaceae Common Name(s): ƃͲƚĂŶŝͲǁĂƚĂƌŝ Synonym(s): Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 27 Aug 2018 WRA Score: 1.0 Designation: L Rating: Low Risk Keywords: Epiphytic, Subtropical, Ornamental, Shade Tolerant, Wind-Dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 ? outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 n 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals 405 Toxic -

Conservation Assessment for Black-Stem Spleenwort (Asplenium Resiliens) Kunze

Conservation Assessment for Black-stem Spleenwort (Asplenium resiliens) Kunze Photo: Jerry Evans USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region January 6, 2003 Steven R. Hill, Ph.D. Illinois Natural History Survey Center for Biodiversity 607 East Peabody Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 This document is undergoing peer review, comments welcome Conservation Assessment for Black-stem Spleenwort (Asplenium resiliens) Kunze This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on the subject taxon or community; or this document was prepared by another organization and provides information to serve as a Conservation Assessment for the Eastern Region of the Forest Service. It does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if you have information that will assist in conserving the subject taxon, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service - Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 580 Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. Conservation Assessment for Black-stem Spleenwort (Asplenium resiliens) Kunze Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................4 NOMENCLATURE -

PTERIDOPHYTES ASPLENIACEAE. the Spleenwort Family. Asplenium

1 PTERIDOPHYTES ?D. celsa (W.Palmer) Knowlton D. goldiana (Hook.) A.Gray. Goldie’s w. f. ♦ ASPLENIACEAE. The Spleenwort Family. D. intermedia (Muhl. ex Willd.) A.Gray. Evergreen w. f. !D. ludoviciana (Kunze) Small. Southern w. f. Asplenium L. Spleenwort. D. marginalis (L.) A.Gray. Marginal w. f. A. bradleyi D.C.Eat. Bradley’s s. A. montanum Willd. Mountain s. Onoclea L. A. pinnatifidum Nutt. Lobed s. O. sensibilis L. Sensitive fern. A. platyneuron (L.) BSP. Ebony s. A. resiliens Kunze. Black-stalked s. Polystichum Roth. A. rhizophyllum L. Walking fern. P. acrostichoides (Michx.) Schott. Christmas fern. A. ruta-muraria L. Wall-rue. A. trichomanes L. Maidenhair s. Woodsia R. Br. Cliff fern. W. obtusa (Spreng.) Torr. Blunt c. f. ♦ AZOLLACEAE. The Mosquito Fern Family. !W. scopulina D.C.Eaton. Mountain c. f. Azolla Lam. ♦ EQUISETACEAE. The Horsetail Family. A. caroliniana Willd. Mosquito fern. ?A. mexicana C.Presl. Equisetum L. Horsetail, scouring-rush. E. arvense L. Field h. ♦ BLECHNACEAE. The Chain Fern Family. E. Xferrissii Clute. E. hyemale L. Common s.-r. Woodwardia Sm. Chain fern. W. areolata (L.) T.Moore. Netted c. f. ♦ HYMENOPHYLLACEAE. The Filmy Fern Family. ♦ DENNSTAEDTIACEAE. The Bracken Family. Trichomanes L. Bristle fern. T. boschianum Sturm. Appalachian b. f. Dennstaedtia Bernh. T. intricatum Farrar. Appalachian trichomanes. D. punctilobula (Michx.) T.Moore. Hay-scented fern. ♦ ISOETACEAE. The Quillwort Family. Pteridium Gled. ex Scop. P. aquilinum (L.) Kuhn. Bracken fern. Isoetes L. Quillwort. var. latiusculum (Desv.) Underw. ex A.Heller !I. butleri Engelm. Butler’s q. var. pseudocaudatum (Clute) A.Heller I. engelmannii A.Braun. Engelmann’s q. -

Flora of New Zealand Ferns and Lycophytes

FLORA OF NEW ZEALAND FERNS AND LYCOPHYTES ATHYRIACEAE P.J. BROWNSEY & L.R. PERRIE Fascicle 24 – OCTOBER 2018 © Landcare Research New Zealand Limited 2018. Unless indicated otherwise for specific items, this copyright work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence Attribution if redistributing to the public without adaptation: “Source: Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research” Attribution if making an adaptation or derivative work: “Sourced from Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research” See Image Information for copyright and licence details for images. CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Brownsey, P. J. (Patrick John), 1948– Flora of New Zealand : ferns and lycophytes. Fascicle 24, Athyriaceae / P.J. Brownsey and L.R. Perrie. -- Lincoln, N.Z.: Manaaki Whenua Press, 2018. 1 online resource ISBN 978-0-9 47525-46-0 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-478-34761-6 (set) 1.Ferns -- New Zealand – Identification. I. Perrie, L. R. (Leon Richard). II. Title. III. Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd. UDC 582.394.742(931) DC 587.30993 DOI: 10.7931/B1XC9M This work should be cited as: Brownsey, P.J. & Perrie, L.R. 2018: Athyriaceae. In: Breitwieser, I.; Wilton, A.D. Flora of New Zealand – Ferns and Lycophytes. Fascicle 24. Manaaki Whenua Press, Lincoln. http://dx.doi.org/10.7931/B1XC9M Cover image: Deparia petersenii subsp. congrua. Mature deeply 1-pinnate-pinnatifid frond. Contents Introduction..............................................................................................................................................1 Taxa -

A Classification for Extant Ferns

55 (3) • August 2006: 705–731 Smith & al. • Fern classification TAXONOMY A classification for extant ferns Alan R. Smith1, Kathleen M. Pryer2, Eric Schuettpelz2, Petra Korall2,3, Harald Schneider4 & Paul G. Wolf5 1 University Herbarium, 1001 Valley Life Sciences Building #2465, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-2465, U.S.A. [email protected] (author for correspondence). 2 Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708-0338, U.S.A. 3 Department of Phanerogamic Botany, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stock- holm, Sweden. 4 Albrecht-von-Haller-Institut für Pflanzenwissenschaften, Abteilung Systematische Botanik, Georg-August- Universität, Untere Karspüle 2, 37073 Göttingen, Germany. 5 Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, Utah 84322-5305, U.S.A. We present a revised classification for extant ferns, with emphasis on ordinal and familial ranks, and a synop- sis of included genera. Our classification reflects recently published phylogenetic hypotheses based on both morphological and molecular data. Within our new classification, we recognize four monophyletic classes, 11 monophyletic orders, and 37 families, 32 of which are strongly supported as monophyletic. One new family, Cibotiaceae Korall, is described. The phylogenetic affinities of a few genera in the order Polypodiales are unclear and their familial placements are therefore tentative. Alphabetical lists of accepted genera (including common synonyms), families, orders, and taxa of higher rank are provided. KEYWORDS: classification, Cibotiaceae, ferns, monilophytes, monophyletic. INTRODUCTION Euphyllophytes Recent phylogenetic studies have revealed a basal dichotomy within vascular plants, separating the lyco- Lycophytes Spermatophytes Monilophytes phytes (less than 1% of extant vascular plants) from the euphyllophytes (Fig.