^ CTEP WRITINGS Edited and Introduced Bv ARTHUR LEHNING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Communist Manifesto

The Communist Manifesto A Study Guide These notes are designed to help new comrades to understand some of the basic ideas of Marxism and how they relate to the politics of the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty (AWL). More experienced comrades leading the educationals can use the tutor notes to expand on certain key ideas and to direct comrades to other reading. Paul Hampton September 2006 1 The Communist Manifesto A Study Guide Contents Background to the Manifesto 3 Questions 5 Further reading 6 Title, preface, preamble 7 I: Bourgeois and Proletarians 9 II: Proletarians and Communists 19 III: Socialist and Communist Literature 27 IV: Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Existing Opposition Parties 32 Glossary 35 2 Background to the Manifesto The text Karl Marx wrote the Manifesto of the Communist Party in German. It was first published in February 1848. It has sometimes been misdated 1847, including in Marx and Engels’ own writings, by Kautsky, Lenin and others. The standard English translation was done by Samuel Moore in 1888 and authorised by Frederick Engels. It can be downloaded from the Marxist Internet Archive http://www.marxists.org.uk/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/index.htm There are scores of other editions by different publishers and with other translations. Between 1848 and 1918, the Manifesto was published in more than 35 languages, in some 544 editions, (Beamish 1998 p.233) The text is also in the Marx and Engels Collected Works (MECW), Volume 6, along with other important articles, drafts and reports from the time. http://www.marxists.org.uk/archive/marx/works/cw/volume06/index.htm The context The Communist Manifesto was written for and published by the Communist League, an organisation founded less than a year before it was written. -

Cannibals and Animals of Capital1

Page 1 of 33 Cannibals and Animals of Capital1 Magnus Møller Ziegler2 Second draft; Spring 2019 For theſe incloſures be the cauſes why rich men eat vp poore men, as beaſts doo eat graſſe : Theſe, I ſay, are the Caterpillers and deuouring locuſtes that maſſacre the poore, & eat vp the whole realme to the deſtruction of the ſame : The Lorde mooue them ! —Philip Stubbes, Anatomy of the Abuses in England (1583)3 INTRODUCTION Years ago, while flicking through the index to Karl Marx’s Capital volume 1, I came across a peculiar entry: ‘cannibalism’. Though there is only one reference—which is found in the chapter on ‘Absolute and Relative Surplus Value’— as any sane person would do, I of course immediately looked it up and forgot all about what it was I had actually been looking for. In the relevant section, Marx writes that, [There] is no natural obstacle absolutely preventing one man from lifting himself from the burden of the labour necessary to maintain his own existence, and imposing it on another, just as there is no unconquerable natural obstacle to the consumption of the flesh of one man by another.4 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at a Ph.D. masterclass with William Clare Roberts at Aarhus University in June 2018. I would like to thank William Clare Roberts, Søren Mau, Jonas Ross Kjærgård, and Signe Leth Gammelgaard for their useful comments, criticisms, and proposals. Thank you also to David Leopold who kindly discussed this paper with me at great length. 2 Ph.D. -

'The Italians and the IWMA'

Levy, Carl. 2018. ’The Italians and the IWMA’. In: , ed. ”Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth”. The First International in Global Perspective. 29 The Hague: Brill, pp. 207-220. ISBN 978-900-4335-455 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/23423/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] chapter �3 The Italians and the iwma Carl Levy Introduction Italians played a significant and multi-dimensional role in the birth, evolution and death of the First International, and indeed in its multifarious afterlives: the International Working Men's Association (iwma) has also served as a milestone or foundation event for histories of Italian anarchism, syndicalism, socialism and communism.1 The Italian presence was felt simultaneously at the national, international and transnational levels from 1864 onwards. In this chapter I will first present a brief synoptic overview of the history of the iwma (in its varied forms) in Italy and abroad from 1864 to 1881. I will then exam- ine interpretations of aspects of Italian Internationalism: Mazzinian Repub- licanism and the origins of anarchism, the Italians, Bakunin and interactions with Marx and his ideas, the theory and practice of propaganda by the deed and the rise of a third-way socialism neither fully reformist nor revolutionary, neither Marxist nor anarchist. -

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939 Sam Dolgoff (editor) 1974 Contents Preface 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introductory Essay by Murray Bookchin 9 Part One: Background 28 Chapter 1: The Spanish Revolution 30 The Two Revolutions by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 30 The Bolshevik Revolution vs The Russian Social Revolution . 35 The Trend Towards Workers’ Self-Management by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 36 Chapter 2: The Libertarian Tradition 41 Introduction ............................................ 41 The Rural Collectivist Tradition by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 41 The Anarchist Influence by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 44 The Political and Economic Organization of Society by Isaac Puente ....................................... 46 Chapter 3: Historical Notes 52 The Prologue to Revolution by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 52 On Anarchist Communism ................................. 55 On Anarcho-Syndicalism .................................. 55 The Counter-Revolution and the Destruction of the Collectives by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 56 Chapter 4: The Limitations of the Revolution 63 Introduction ............................................ 63 2 The Limitations of the Revolution by Gaston Leval ....................................... 63 Part Two: The Social Revolution 72 Chapter 5: The Economics of Revolution 74 Introduction ........................................... -

Inspiration for the Struggle . Fr Ull W

Page Six THE DAILY WORKER THE DAILY WORKER. A Wise Fool Speaketh - Published by the DAILY WORKER PUBLISHING 00. It is said somewhere in the bible that the “truth Inspiration for the Struggle . fr Ull W. Washington Bird.. Chicago, QL shall be spoken out of the mouths of fools.” Per- it to the affiliated clubs tor discussion. , Manifesto’; fully (Phone: Monroe 4712) for inasmuch as It must prepared document Each one of haps in biblical days as today only those to whom Introduction to Engels’ “The Prin- This draft also reached Paris, where i deal more or less with history, the its sentences stands out like a work ciples of Communism,” No. 3 Moses Hess, a “philosophical” social- previously accepted style does not fit SUBSCRIPTION RATES truth was dearer than ■ of art hewn in granite. Altho a docu- material success said what of the Little Red Library. ist, made what he thought im- at I’ll bring with me the By mall: were ■ all. one that ment prepared for the political strug- Ed. Note. ! they wanted —This booklet of the Little provements and prevailed upon the here. ~ It-tS par year 93.50....A months »100._.i months I to say instead of what should be I made J begin: What is gles of the hour of Its publication and Red Library can be had from the Faris club to accept this document. , Communism? And then right after problems By mail (In Chicago only): said. The biblical quotation above seems to fit tho dealing with character- f 1.06 per year months $2.50._9 months DAILY WORKER Publishing Co.— But in a later meeting the decision . -

The Italians and the Iwma

chapter �3 The Italians and the iwma Carl Levy Introduction Italians played a significant and multi-dimensional role in the birth, evolution and death of the First International, and indeed in its multifarious afterlives: the International Working Men's Association (iwma) has also served as a milestone or foundation event for histories of Italian anarchism, syndicalism, socialism and communism.1 The Italian presence was felt simultaneously at the national, international and transnational levels from 1864 onwards. In this chapter I will first present a brief synoptic overview of the history of the iwma (in its varied forms) in Italy and abroad from 1864 to 1881. I will then exam- ine interpretations of aspects of Italian Internationalism: Mazzinian Repub- licanism and the origins of anarchism, the Italians, Bakunin and interactions with Marx and his ideas, the theory and practice of propaganda by the deed and the rise of a third-way socialism neither fully reformist nor revolutionary, neither Marxist nor anarchist. This chapter will also include some brief words on the sociology and geography of Italian Internationalism and a discussion of newer approaches that transcend the rather stale polemics between parti- sans of a Marxist or anarchist reading of Italian Internationalism and incorpo- rates themes that have enlivened the study of the Risorgimento, namely, State responses to the International, the role of transnationalism, romanticism, 1 The best overviews of the iwma in Italy are: Pier Carlo Masini, La Federazione Italiana dell’Associazione Internazionale dei Lavoratori. Atti ufficiali 1871–1880 (atti congressuali; indirizzi, proclaim, manifesti) (Milan, 1966); Pier Carlo Masini, Storia degli Anarchici Ital- iani da Bakunin a Malatesta, (Milan, (1969) 1974); Nunzio Pernicone, Italian Anarchism 1864–1892 (Princeton, 1993); Renato Zangheri, Storia del socialismo italiano. -

Left Hegelianism, Arab Nationalism, and Labor Zionism

Left Hegelianism, Arab Nationalism, and Labor Zionism by Stephen P. Halbrook Virginia State Bar A significant portion of the conflicting leftist ideologies of the contem- porary Middle East -in particular, the socialist philosophies of both Arabs and Israelis-is an outgrowth of nineteenth-century social theories and philosophies of history originating from a group of individuals who at one point constituted the Young Hegelians. Moses Hess, Michael Bakunin, Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, the respective founders of Zionist socialism, anarchist socialism, and Marxist socialism, were associates in Berlin and Paris in the 1840's who attempted to apply the thought of Hegel to revolu- tionary, democratic, and communist ideas. While traditional and modern- istic interpretations of Jewish and Arab world views obviously influenced the development of Zionism and Arab nationalism, the ideological roots of the socialist varieties of these philosophies may be traced in part to the con- tributions of the left Hegelians. A key to the comprehension of the philo- sophical outlooks of political forces as diverse as the Labor Party of Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization may be found in the comparison and contrast of the thought of Hess, Bakunin, Marx and Engels. Hegel's philosophy of history not only expressed prevailing European perceptions of Middle Eastern peoples but also influenced some (but not all) of the left Heeelians in respect to the auestion of colonialism as a modern- izing force. ~h~omo~vineii, perhaps ;he most significant Marxist Zionist philospher and whose interpretations of Marxism contribute to the central ihesis of this essay, has sumharized Hegel's earliest analysis of the Oriental world in these terms: The oriental nations are characterized. -

SAR M. Le Mouvement Anarchiste En Espagne. Pouvoir Et RÉ

502 Book reviews Lorenzo, Ce´sar M. Le mouvement anarchiste en Espagne. Pouvoir et re´volution sociale. Les E´ ditions Libertaires, S.l. 2006. 559 pp. A 35.00. DOI: S0020859007023267 This is a revised, updated, and considerably expanded edition of a study which first appeared in 1969. The bulk of it is divided into four parts, which provide a more or less chronological account. Part 1 covers the rise of a libertarian workers’ movement, analysing its ideological foundations, and tracing its development from the September Revolution of 1868 to the CNT’s Saragossa conference of May 1936. Part 2 provides a ‘‘panorama’’ of the revolution of July 1936, each chapter analysing the revolutionary political structures thrown up in different parts of the country, and the role played within them by the CNT. Part 3 concentrates on ‘‘the civil war within the civil war’’, from the autumn of 1936 through the counter-revolution of May 1937 to the CNT’s relations with the Negrin government; it also examines the strengths and weaknesses of the collectivizations (still a seriously under-researched area). The shorter Part 4 analyses what the author calls the ‘‘period of decadence and retreat’’ from the defeat of 1939 through to the experience of exile and the divisions of the post-Franco era. In a thirty-seven-page ‘‘appendix’’, Lorenzo addresses critically the various more or less dubious attempts to explain why there has been, as the French anarchist Louis Lecoin once put it, ‘‘no other country where Anarchism has put down such deep roots as in Spain’’.1 Whilst rejecting what he bluntly dismisses as ‘‘racist’’ attempts at explanation and praising the work of some Marxist historians (Pierre Vilar, notably), Lorenzo goes on to analyse Spanish culture and the set of values and attitudes which, he argues, left their mark on what would become a distinctively Spanish anarchism. -

Alberto Corsín Jiménez

CHAPTER FOUR AUTONOMIA ETHNOGRAPHICA Liberal Designs, Designs for Liberation, and the Liberation of Design Alberto Corsín Jiménez This chapter develops an argument about the relation between autonomy and ethnography—in particular, about autonomy as an experimental design in political and anthropological praxis. I am interested in what I call autonomia ethnographica: the pressures and challenges confronting the mise-en-scénes of anthropological fieldwork today and the sometimes troubled, sometimes conflictive, yet ultimately liberating arrangements in complicity and complexity through which anthropologists construct the conditions for ethnographic practice and description. The concept of autonomy I am summoning here needs a little unpacking. In some respects, autonomy is undergoing somewhat of a comeback in social and political theory (Nelson and Braun 2017; Luisetti et al. 2015). Most famously deployed by the Italian operaist (workers) movement in the 1950s in the context of accelerating and exploitative labor conditions in the automobile industry, “autonomia” was invoked at the time to describe a revolutionary impulse for the ontological self-determination of workers’ power—the power, as it was referred to at the time, to “refuse to work” (Virno 1996) and in this capacity to disengage from, and invent novel imaginative alternatives to, the spatial and temporal matrices of the state-capital nexus (Aureli 2008). Throughout the 1970s, however, “autonomia” gradually lost its attachment to workers’ power, leaving the factory floor for the street protests of students, feminists, and environmental activists. Thus, a second generation of “diffuse autonomy” was born, a new wave of insurrectional and intersectional politics (Cuninghame 2013), which, in the wake of the alter- globalization movement in the late 1990s, entered also the Anglophone academy under the 1 liberation aesthetics of networked-mediated multitudes and commons (Hardt and Negri 2005; 2009). -

DARI ZIONISME KE TEORI KONSPIRASI: Survey Bibliografis Karya Sarjana Muslim Indonesia Kontemporer Tentang Agama Dan Umat Yahudi

LAPORAN AKHIR PENELITIAN KOMPETITIF DARI ZIONISME KE TEORI KONSPIRASI: Survey Bibliografis Karya Sarjana Muslim Indonesia Kontemporer tentang Agama dan Umat Yahudi Oleh: Ismatu Ropi Dadi Darmadi Rifqi Muhammad Fatkhi 2013 LAPORAN AKHIR PENELITIAN KOMPETITIF DARI ZIONISME KE TEORI KONSPIRASI: Survey Bibliografis Karya Sarjana Muslim Indonesia Kontemporer tentang Agama dan Umat Yahudi Diserahkan Kepada: Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian kepada Masyarakat (LP2M) Pusat Penelitian dan Penerbitan UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta Oleh: Ismatu Ropi Dadi Darmadi Rifqi Muhammad Fatkhi 2013 KATA PENGANTAR Segala puji dipanjatkan kepada Allah SWT sebagai ungkapan rasa syukur atas rahmatnya kepada kita semua. Salawat dan salam juga dihaturkan kepada Nabi Muahmmad SAW yang telah memberikan bimbingan kepada kita semua. Laporan berkenaan dengan penelitian Dari Zionisme Ke Teori Konspirasi: Survey Bibliografis Karya Sarjana Muslim Indonesia Kontemporer tentang Agama dan Umat Yahudi ini merupakan bagian dari penguatan dan pengembangan sumber dana manusia dalam bentuk riset dan pengkajian di lingkungan UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta tahun 2013. Penelitian ini dapat dilakukan sebagai bagian dari hibah penelitian kompetitif bagi para dosen dan tenaga pengajar di UIN Jakarta melalui Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian kepada Masyarakat (LP2M) UIN Jakarta c.q. Pusat Penelitian dan Penerbitan tahun anggaran 2012-2013. Oleh karena itu, kami mengucapkan banyak terima kasih kepada Rektor UIN Syarif Hidayatullah atas segala bantuan dan dukungan yang diberikan sehingga penelitian ini bisa berjalan dengan sebaik-baiknya. Ucapan terima kasih juga disampaikan kepada Kepala dan para staf di kantor Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian kepada Masyarakat (LP2M) c.q. Pusat Penelitian dan Penerbitan UIN Jakarta yang memberikan banyak kemudahan dan bantuan teknis bagi pelaksanaan penelitian ini. Terima kasih juga disampaikan i kepada berbagai pihak yang membantu baik dalam pengumpulan data maupun saran untuk penyempurnaan penelitian ini. -

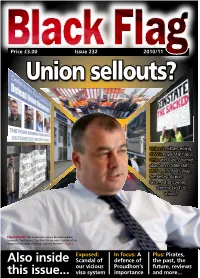

Also Inside This Issue

PricePrice £3.00 £3.00 IssueIssue 232 229 Mid 2010/11 2009 Union sellouts? Unison’s militant exiling, CWU’s Royal Mail fiasco, Unite and Gate Gourmet, abandoned Mitie staff, NUT and St Paul’s Way, the Belfast Airport farce... what’s wrong with the big TUC unions? Figurehead: TUC general secretary Brendan Barber lambasts “bad bosses,” but do the member unions of his organisation really stand up when it matters? Page 7 Exposed: In focus: A Plus: Pirates, Also inside Scandal of defence of the past, the our vicious Proudhon’s future, reviews this issue... visa system importance and more... Editorial Welcome to issue 232 of Black Flag, which coincides once again with the annual London Anarchist Bookfair, the largest and longest-running event of its kind in the world. Now that this issue is the 7th published by the “new” collective we can safely drop the “new” bit! We believe that we have come a long way with Black Flag. As a very small collective we have managed to publish and sustain a consistent and high-quality, twice yearly, class- struggle anarchist publication on a shoe-string budget and limited personnel. Before proceeding further, we would like to make our usual appeal for more people to get involved with the editorial group. The more people who get involved, the more Black Flag will grow with increased frequency and wider distribution etc. This issue includes our usual eclectic mix of libertarian-left theory, history, debate, analysis and reportage. Additionally, this issue is again somewhat of an anniversary issue, which acknowledges two significant events. -

Karl Marx and the Iwma Revisited 299 Jürgen Herres

“Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth” <UN> Studies in Global Social History Editor Marcel van der Linden (International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Editorial Board Sven Beckert (Harvard University, Cambridge, ma, usa) Dirk Hoerder (University of Arizona, Phoenix, ar, usa) Chitra Joshi (Indraprastha College, Delhi University, India) Amarjit Kaur (University of New England, Armidale, Australia) Barbara Weinstein (New York University, New York, ny, usa) volume 29 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/sgsh <UN> “Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth” The First International in a Global Perspective Edited by Fabrice Bensimon Quentin Deluermoz Jeanne Moisand leiden | boston <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Cover illustration: Bannière de la Solidarité de Fayt (cover and back). Sources: Cornet Fidèle and Massart Théophile entries in Dictionnaire biographique du mouvement ouvrier en Belgique en ligne : maitron-en -ligne.univ-paris1.fr. Copyright : Bibliothèque et Archives de l’IEV – Brussels. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bensimon, Fabrice, editor. | Deluermoz, Quentin, editor. | Moisand, Jeanne, 1978- editor. Title: “Arise ye wretched of the earth” : the First International in a global perspective / edited by Fabrice Bensimon, Quentin Deluermoz, Jeanne Moisand. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2018] | Series: Studies in global social history, issn 1874-6705 ; volume 29 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018002194 (print) | LCCN 2018004158 (ebook) | isbn 9789004335462 (E-book) | isbn 9789004335455 (hardback : alk.