Left Hegelianism, Arab Nationalism, and Labor Zionism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Communist Manifesto

The Communist Manifesto A Study Guide These notes are designed to help new comrades to understand some of the basic ideas of Marxism and how they relate to the politics of the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty (AWL). More experienced comrades leading the educationals can use the tutor notes to expand on certain key ideas and to direct comrades to other reading. Paul Hampton September 2006 1 The Communist Manifesto A Study Guide Contents Background to the Manifesto 3 Questions 5 Further reading 6 Title, preface, preamble 7 I: Bourgeois and Proletarians 9 II: Proletarians and Communists 19 III: Socialist and Communist Literature 27 IV: Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Existing Opposition Parties 32 Glossary 35 2 Background to the Manifesto The text Karl Marx wrote the Manifesto of the Communist Party in German. It was first published in February 1848. It has sometimes been misdated 1847, including in Marx and Engels’ own writings, by Kautsky, Lenin and others. The standard English translation was done by Samuel Moore in 1888 and authorised by Frederick Engels. It can be downloaded from the Marxist Internet Archive http://www.marxists.org.uk/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/index.htm There are scores of other editions by different publishers and with other translations. Between 1848 and 1918, the Manifesto was published in more than 35 languages, in some 544 editions, (Beamish 1998 p.233) The text is also in the Marx and Engels Collected Works (MECW), Volume 6, along with other important articles, drafts and reports from the time. http://www.marxists.org.uk/archive/marx/works/cw/volume06/index.htm The context The Communist Manifesto was written for and published by the Communist League, an organisation founded less than a year before it was written. -

Cannibals and Animals of Capital1

Page 1 of 33 Cannibals and Animals of Capital1 Magnus Møller Ziegler2 Second draft; Spring 2019 For theſe incloſures be the cauſes why rich men eat vp poore men, as beaſts doo eat graſſe : Theſe, I ſay, are the Caterpillers and deuouring locuſtes that maſſacre the poore, & eat vp the whole realme to the deſtruction of the ſame : The Lorde mooue them ! —Philip Stubbes, Anatomy of the Abuses in England (1583)3 INTRODUCTION Years ago, while flicking through the index to Karl Marx’s Capital volume 1, I came across a peculiar entry: ‘cannibalism’. Though there is only one reference—which is found in the chapter on ‘Absolute and Relative Surplus Value’— as any sane person would do, I of course immediately looked it up and forgot all about what it was I had actually been looking for. In the relevant section, Marx writes that, [There] is no natural obstacle absolutely preventing one man from lifting himself from the burden of the labour necessary to maintain his own existence, and imposing it on another, just as there is no unconquerable natural obstacle to the consumption of the flesh of one man by another.4 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at a Ph.D. masterclass with William Clare Roberts at Aarhus University in June 2018. I would like to thank William Clare Roberts, Søren Mau, Jonas Ross Kjærgård, and Signe Leth Gammelgaard for their useful comments, criticisms, and proposals. Thank you also to David Leopold who kindly discussed this paper with me at great length. 2 Ph.D. -

Inspiration for the Struggle . Fr Ull W

Page Six THE DAILY WORKER THE DAILY WORKER. A Wise Fool Speaketh - Published by the DAILY WORKER PUBLISHING 00. It is said somewhere in the bible that the “truth Inspiration for the Struggle . fr Ull W. Washington Bird.. Chicago, QL shall be spoken out of the mouths of fools.” Per- it to the affiliated clubs tor discussion. , Manifesto’; fully (Phone: Monroe 4712) for inasmuch as It must prepared document Each one of haps in biblical days as today only those to whom Introduction to Engels’ “The Prin- This draft also reached Paris, where i deal more or less with history, the its sentences stands out like a work ciples of Communism,” No. 3 Moses Hess, a “philosophical” social- previously accepted style does not fit SUBSCRIPTION RATES truth was dearer than ■ of art hewn in granite. Altho a docu- material success said what of the Little Red Library. ist, made what he thought im- at I’ll bring with me the By mall: were ■ all. one that ment prepared for the political strug- Ed. Note. ! they wanted —This booklet of the Little provements and prevailed upon the here. ~ It-tS par year 93.50....A months »100._.i months I to say instead of what should be I made J begin: What is gles of the hour of Its publication and Red Library can be had from the Faris club to accept this document. , Communism? And then right after problems By mail (In Chicago only): said. The biblical quotation above seems to fit tho dealing with character- f 1.06 per year months $2.50._9 months DAILY WORKER Publishing Co.— But in a later meeting the decision . -

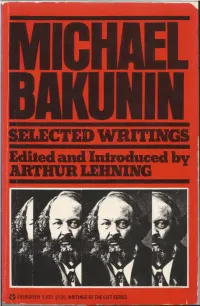

^ CTEP WRITINGS Edited and Introduced Bv ARTHUR LEHNING

IGHAEL ^■ CTEP WRITINGS Edited and Introduced bv ARTHUR LEHNING ^ EVERGREEN E-629 $4.95 WRITINGS OF THE LEFT SERIES WRITINGS OF THE LEFT General Editor: ralph miliband Professor o f Politics at Leeds University MICHAEL BAKUNIN SELECTED WRITINGS MICHAEL BAKUNIN SELECTED WRITINGS Edited and Introduced by ARTHUR LEHNING Editor Archives Bakounine, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam Translations from the French by STEVEN cox Translations from the Russian by OLIVE STEVENS JONATHAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON THIS COMPILATION FIRST PUBLISHED 1973 INTRODUCTION AND COMPILATION © 1973 BY ARTHUR LEHNING TRANSLATIONS BY STEVEN COX AND OLIVE STEVENS © 1973 BY JONATHAN CAPE LTD JONATHAN CAPE LTD, 30 BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON WCI Hardback edition isb n o 224 00893 5 Paperback edition isb n o 224 00898 6 Condition o f Sale This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated with out the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition in cluding this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY EBENEZER BAYLIS AND SON LTD THE TRINITY PRESS, WORCESTER AND LONDON GENERAL EDITOR’S PREFACE It is often claimed nowadays that terms like Left and Right have ceased to mean very much. This is not true: the distinc tion endures, in as sharp a form as ever, between those who, on the one hand, accept as given the framework, if not all the features, of capitalist society; and those who, on the other, are concerned with and work for the establishment of a socialist alternative to the here and now. -

DARI ZIONISME KE TEORI KONSPIRASI: Survey Bibliografis Karya Sarjana Muslim Indonesia Kontemporer Tentang Agama Dan Umat Yahudi

LAPORAN AKHIR PENELITIAN KOMPETITIF DARI ZIONISME KE TEORI KONSPIRASI: Survey Bibliografis Karya Sarjana Muslim Indonesia Kontemporer tentang Agama dan Umat Yahudi Oleh: Ismatu Ropi Dadi Darmadi Rifqi Muhammad Fatkhi 2013 LAPORAN AKHIR PENELITIAN KOMPETITIF DARI ZIONISME KE TEORI KONSPIRASI: Survey Bibliografis Karya Sarjana Muslim Indonesia Kontemporer tentang Agama dan Umat Yahudi Diserahkan Kepada: Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian kepada Masyarakat (LP2M) Pusat Penelitian dan Penerbitan UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta Oleh: Ismatu Ropi Dadi Darmadi Rifqi Muhammad Fatkhi 2013 KATA PENGANTAR Segala puji dipanjatkan kepada Allah SWT sebagai ungkapan rasa syukur atas rahmatnya kepada kita semua. Salawat dan salam juga dihaturkan kepada Nabi Muahmmad SAW yang telah memberikan bimbingan kepada kita semua. Laporan berkenaan dengan penelitian Dari Zionisme Ke Teori Konspirasi: Survey Bibliografis Karya Sarjana Muslim Indonesia Kontemporer tentang Agama dan Umat Yahudi ini merupakan bagian dari penguatan dan pengembangan sumber dana manusia dalam bentuk riset dan pengkajian di lingkungan UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta tahun 2013. Penelitian ini dapat dilakukan sebagai bagian dari hibah penelitian kompetitif bagi para dosen dan tenaga pengajar di UIN Jakarta melalui Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian kepada Masyarakat (LP2M) UIN Jakarta c.q. Pusat Penelitian dan Penerbitan tahun anggaran 2012-2013. Oleh karena itu, kami mengucapkan banyak terima kasih kepada Rektor UIN Syarif Hidayatullah atas segala bantuan dan dukungan yang diberikan sehingga penelitian ini bisa berjalan dengan sebaik-baiknya. Ucapan terima kasih juga disampaikan kepada Kepala dan para staf di kantor Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian kepada Masyarakat (LP2M) c.q. Pusat Penelitian dan Penerbitan UIN Jakarta yang memberikan banyak kemudahan dan bantuan teknis bagi pelaksanaan penelitian ini. Terima kasih juga disampaikan i kepada berbagai pihak yang membantu baik dalam pengumpulan data maupun saran untuk penyempurnaan penelitian ini. -

Nur Sayyid Santoso Kristeva, M.A

Sekolah Analisis Sosial (SAS) Pergerakan Mahasiswa Islam Indonesia (PMII) NUR SAYYID SANTOSO KRISTEVA, M.A. Diterbitkan atas solidaritas, dukungan dan kerjasama: Institute for Philosophical and Social Studies (INSPHISOS), Komunitas Diskusi Progressif: Eye On The Revolution & Revolusi Demokratik, Jaringan Inti Ideologis Pergerakan Mahasiswa Islam Indonesia (PMII). Anti-Copyright © 2014, dicetak, diterbitkan dan disebarkan untuk kebutuhan amunisi intelektual Kader Inti Ideologis dan kebutuhan gerakan sosial. 1 Sekolah Analisis Sosial (SAS) Pergerakan Mahasiswa Islam Indonesia (PMII) BUKU PANDUAN SEKOLAH ANALISIS SOSIAL PERGERAKAN MAHASISWA ISLAM INDONESIA (PMII) Nur Sayyid Santoso Kristeva,M.A. © Insphisos, Eye On The Revolution & Revdem, PMII, 2014. [PARADIGMA ILMU-ILMU SOSIAL & PERUBAHAN SOSIALDINAMIKA PERUBAHAN SOSIAL INDONESIAPROTES SOSIAL, REFORMASI POLITIK DAN GERAKAN SOSIALSTRATEGI GERAKAN SOSIAL: MEMBEDAH RELASI NEGARA & MASYARAKATMARXISME, IDEOLOGI KAPITALISME, SOSIALISME, KOMUNISMEKERANGKA PIKIR REVOLUSI SOSIAL & REVOLUSI POLITIKANALISIS GEO-EKONOMI, SOSIAL DAN POLITIKPETA DAN LANGKAH PRAXIS ANALISIS SOSIALSTUDI DASAR ADVOKASIMANAJEMEN DAN RESOLUSI KONFLIKANALISIS WACANA MEDIA (MEDIA DISCOURSE ANALYSIS)PARADIGMA ANALISIS WACANA MEDIA (MODEL TEUN A VAN DIJK)TEHNIK AGITASI, ORASI & PROPAGANDATEHNIK DAN MANAJEMEN AKSI MASSATEHNIK LOBBY DAN NEGOSIASIPENGORGANISASIAN MASYARAKAT (CO)] Disusun Oleh: Nur Sayyid Santoso Kristeva, M.A. HP. 085 647 634 312/ E-Mail: [email protected]. Alumnus (S.1) UIN Sunan Kalijaga Jogjakarta, Alumnus -

PHILOSOPHICAL (PRE)OCCUPATIONS and the PROBLEM of IDEALISM: from Ideology to Marx’S Critique of Mental Labor

PHILOSOPHICAL (PRE)OCCUPATIONS AND THE PROBLEM OF IDEALISM: From Ideology to Marx’s Critique of Mental Labor by Ariane Fischer Magister, 1999, Freie Universität Berlin M.A., 2001, The Ohio State University M.Phil., 2005, The George Washington University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2010 Dissertation directed by Andrew Zimmerman Associate Professor of History The Columbian College of The George Washington University certifies that Ariane Fischer has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 25, 2009. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. PHILOSOPHICAL (PRE)OCCUPATIONS AND THE PROBLEM OF IDEALISM: From Ideology to Marx’s Critique of Mental Labor Ariane Fischer Dissertation Research Committee: Andrew Zimmerman, Associate Professor of History, Dissertation Director Peter Caws, University Professor of Philosophy, Committee Member Gail Weiss, Professor of Philosophy, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2010 by Ariane Fischer All rights reserved iii Acknowledgments The author wishes to thank her dissertation advisor Andrew Zimmerman, who has been a continuous source of support and encouragement. His enthusiastic yet demanding guidance has been invaluable. Both his superior knowledge of history and theory as well as his diligence in reviewing drafts have been crucial in the successful completion of the research and writing process. Further, many thanks are extended to Gail Weiss and Peter Caws for joining the dissertation committee, and to Dan Moschenberg and Paul Smith for agreeing to be readers. -

The Rise and Fall of Communism

The Rise and Fall of Communism archie brown To Susan and Alex, Douglas and Tamara and to my grandchildren Isobel and Martha, Nikolas and Alina Contents Maps vii A Note on Names viii Glossary and Abbreviations x Introduction 1 part one: Origins and Development 1. The Idea of Communism 9 2. Communism and Socialism – the Early Years 26 3. The Russian Revolutions and Civil War 40 4. ‘Building Socialism’: Russia and the Soviet Union, 1917–40 56 5. International Communism between the Two World Wars 78 6. What Do We Mean by a Communist System? 101 part two: Communism Ascendant 7. The Appeals of Communism 117 8. Communism and the Second World War 135 9. The Communist Takeovers in Europe – Indigenous Paths 148 10. The Communist Takeovers in Europe – Soviet Impositions 161 11. The Communists Take Power in China 179 12. Post-War Stalinism and the Break with Yugoslavia 194 part three: Surviving without Stalin 13. Khrushchev and the Twentieth Party Congress 227 14. Zig-zags on the Road to ‘communism’ 244 15. Revisionism and Revolution in Eastern Europe 267 16. Cuba: A Caribbean Communist State 293 17. China: From the ‘Hundred Flowers’ to ‘Cultural Revolution’ 313 18. Communism in Asia and Africa 332 19. The ‘Prague Spring’ 368 20. ‘The Era of Stagnation’: The Soviet Union under Brezhnev 398 part four: Pluralizing Pressures 21. The Challenge from Poland: John Paul II, Lech Wałesa, and the Rise of Solidarity 421 22. Reform in China: Deng Xiaoping and After 438 23. The Challenge of the West 459 part five: Interpreting the Fall of Communism 24. -

An Anthropology of Marxism

An Anthropology of Marxism CEDRIC J. ROBINSON University of California at Santa Barbara, USA Ash gate Aldershot • Burlington USA • Singapore • Sydney qzgr;; tr!'W"Ulr:!!PW Wf' I • rtft"lrt ri!W:t!ri:!tlu • nw i!HI*oo · " • , ., © Cedric J. Robinson 2001 Contents All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or othetwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Preface Published by Coming to Terms with Marxian Taxonomy Ashgate Publishing Limited 23 Gower House 2 The Social Origins ofMaterialism and Socialism Croft Road 75 Aldershot 3 German Critical Philosophy and Marx Hampshire GUll 3HR llJ England 4 The Discourse on Economics !51 Ash gate Publishing Company 5 Reality and its Representation 13 I Main Street 161 Burlington, VT 05401-5600 USA Index IAshgate website: http://www.ashgate.com j British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Robinson, Cedric J. An anthropology of Marxism.- (Race and representation) !.Communism 2.Socialism I. Title 335.4 Library of Congress Control Number: 00-111546 ISBN 1 84014 700 8 Printed and bound in Great Brit~in by MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall v qzgr;; tr!'W"Ulr:!!PW Wf' I • rtft"lrt ri!W:t!ri:!tlu • nw i!HI*oo · " • , ., © Cedric J. Robinson 2001 Contents All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or othetwise without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Requiem for Marx and the Social and Economic Systems Created in His Name

REQUIEM for RX Edited with an introduction by Yuri N. Maltsev ~~G Ludwig von Mises Institute l'VIISes Auburn University, Alabama 36849-5301 INSTITUTE Copyright © 1993 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute All rights reserved. Written permission must be secured from the publisher to use or reproduce any part of this book, except for brief quotations in critical review or articles. Published by Praxeology Press of the Ludwig von Mises Institute, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama 36849. Printed in the United States ofAmerica. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 93-083763 ISBN 0-945466-13-7 Contents Introduction Yuri N. Maltsev ........................... 7 1. The Marxist Case for Socialism David Gordon .......................... .. 33 2. Marxist and Austrian Class Analysis Hans-Hermann Hoppe. .................. .. 51 3. The Marx Nobody Knows Gary North. ........................... .. 75 4. Marxism, Method, and Mercantilism David Osterfeld ........................ .. 125 5. Classical Liberal Roots ofthe Marxist Doctrine of Classes Ralph Raico ........................... .. 189 6. Karl Marx: Communist as Religious Eschatologist Murray N. Rothbard 221 Index 295 Contributors 303 5 The Ludwig von Mises Institute gratefully acknowledges the generosity ofits Members, who made the publication of this book possible. In particular, it wishes to thank the following Patrons: Mark M. Adamo James R. Merrell O. P. Alford, III Dr. Matthew T. Monroe Anonymous (2) Lawrence A. Myers Everett Berg Dr. Richard W. Pooley EBCO Enterprises Dr. Francis Powers Burton S. Blumert Mr. and Mrs. Harold Ranstad John Hamilton Bolstad James M. Rodney Franklin M. Buchta Catherine Dixon Roland Christopher P. Condon Leslie Rose Charles G. Dannelly Gary G. Schlarbaum Mr. and Mrs. William C. Daywitt Edward Schoppe, Jr. -

In Socialism's Twilight: Michael Walzer and the Politics of the Long New

In Socialism’s Twilight: Michael Walzer and the Politics of the Long New Left David Marcus Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 ©2019 David Marcus All Rights Reserved Abstract “In Socialism’s Twilight: Michael Walzer and the Politics of the Long New Left” David Marcus In Socialism’s Twilight is a study of the thought and politics of Michael Walzer and the travails of “democratic socialism” in the second half of the twentieth century. Using the methods of intel- lectual and political history, it situates Walzer’s political theory and criticism in the context of what might be called the “long New Left,” the overlapping generations of radicals that stretched from the beginning of the Cold War to its end and that supplemented the left’s traditional com- mitments to socialism with a politics of national liberation, radical democracy, and liberalism. By doing so, the dissertation hopes to trace the development not only of Walzer’s own commit- ments but also those of the socialist left. Caught in a period of frequent defeat and bitter contro- versy, socialists found themselves forced into a state of constant revision, as they moved from the libertarian socialism of the 1950s and 60s to the social democratic coalitions of the 1970s and 80s to the liberalism and humanitarianism of the 1990s and 2000s. Opening with the collapse of the Popular Front after World War II, the study follows Walzer’s search for a new left with radi- cals around Dissent and through his involvement in civil rights and antiwar activism. -

From Eco-Marxism to Ecological Civilisation, Part 2

1 Capitalism, Nature, Socialism. Published online 3rd Sept. 2020 https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2020.1811364 After Neoliberalism: From Eco-Marxism to Ecological Civilisation, Part 2 Arran Gare Philosophy and Cultural Inquiry, Department of Social Sciences, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, Australia [email protected] Abstract This is Part 2 of an article aimed at defending Marx against orthodox Marxists to reveal the possibilities for overcoming capitalism. It is argued that Marx’s general theory of history is inconsistent with his profound insights into alienation and commodity fetishism as the foundations of capitalism. Humanist Marxists focused on the latter in opposition to Orthodox Marxists, but without fully acknowledging this inconsistency and its implications, failed to realize the full potential of Marx’s work. The outcome has been the triumph of “neoliberalism”, effectively a synthesis of the worst aspects of capitalism with Soviet managerialism. In Part 1 of this article I critiqued orthodox Marxism and utilized recent scholarship examining the penultimate drafts of Capital to reinterpret his work. The legacy of orthodox Marxism is still standing in the way of efforts to replace capitalism, however. In Part 2 I argue that the call for an “ecological civilization” brings into focus what is required: a realistic vision of the future based on ecological concepts. Keywords Eco-Marxism; Eco-socialism; Eco-civilisation; Ecology; Human ecology Introduction: Eco-Marxism and Process Philosophy In Part I of this paper I argued that to realize the full potential of Marx’s work it is necessary to free it from the influence of orthodox Marxism.