Luis Araquistáin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Italians and the IWMA'

Levy, Carl. 2018. ’The Italians and the IWMA’. In: , ed. ”Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth”. The First International in Global Perspective. 29 The Hague: Brill, pp. 207-220. ISBN 978-900-4335-455 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/23423/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] chapter �3 The Italians and the iwma Carl Levy Introduction Italians played a significant and multi-dimensional role in the birth, evolution and death of the First International, and indeed in its multifarious afterlives: the International Working Men's Association (iwma) has also served as a milestone or foundation event for histories of Italian anarchism, syndicalism, socialism and communism.1 The Italian presence was felt simultaneously at the national, international and transnational levels from 1864 onwards. In this chapter I will first present a brief synoptic overview of the history of the iwma (in its varied forms) in Italy and abroad from 1864 to 1881. I will then exam- ine interpretations of aspects of Italian Internationalism: Mazzinian Repub- licanism and the origins of anarchism, the Italians, Bakunin and interactions with Marx and his ideas, the theory and practice of propaganda by the deed and the rise of a third-way socialism neither fully reformist nor revolutionary, neither Marxist nor anarchist. -

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939 Sam Dolgoff (editor) 1974 Contents Preface 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introductory Essay by Murray Bookchin 9 Part One: Background 28 Chapter 1: The Spanish Revolution 30 The Two Revolutions by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 30 The Bolshevik Revolution vs The Russian Social Revolution . 35 The Trend Towards Workers’ Self-Management by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 36 Chapter 2: The Libertarian Tradition 41 Introduction ............................................ 41 The Rural Collectivist Tradition by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 41 The Anarchist Influence by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 44 The Political and Economic Organization of Society by Isaac Puente ....................................... 46 Chapter 3: Historical Notes 52 The Prologue to Revolution by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 52 On Anarchist Communism ................................. 55 On Anarcho-Syndicalism .................................. 55 The Counter-Revolution and the Destruction of the Collectives by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 56 Chapter 4: The Limitations of the Revolution 63 Introduction ............................................ 63 2 The Limitations of the Revolution by Gaston Leval ....................................... 63 Part Two: The Social Revolution 72 Chapter 5: The Economics of Revolution 74 Introduction ........................................... -

The Italians and the Iwma

chapter �3 The Italians and the iwma Carl Levy Introduction Italians played a significant and multi-dimensional role in the birth, evolution and death of the First International, and indeed in its multifarious afterlives: the International Working Men's Association (iwma) has also served as a milestone or foundation event for histories of Italian anarchism, syndicalism, socialism and communism.1 The Italian presence was felt simultaneously at the national, international and transnational levels from 1864 onwards. In this chapter I will first present a brief synoptic overview of the history of the iwma (in its varied forms) in Italy and abroad from 1864 to 1881. I will then exam- ine interpretations of aspects of Italian Internationalism: Mazzinian Repub- licanism and the origins of anarchism, the Italians, Bakunin and interactions with Marx and his ideas, the theory and practice of propaganda by the deed and the rise of a third-way socialism neither fully reformist nor revolutionary, neither Marxist nor anarchist. This chapter will also include some brief words on the sociology and geography of Italian Internationalism and a discussion of newer approaches that transcend the rather stale polemics between parti- sans of a Marxist or anarchist reading of Italian Internationalism and incorpo- rates themes that have enlivened the study of the Risorgimento, namely, State responses to the International, the role of transnationalism, romanticism, 1 The best overviews of the iwma in Italy are: Pier Carlo Masini, La Federazione Italiana dell’Associazione Internazionale dei Lavoratori. Atti ufficiali 1871–1880 (atti congressuali; indirizzi, proclaim, manifesti) (Milan, 1966); Pier Carlo Masini, Storia degli Anarchici Ital- iani da Bakunin a Malatesta, (Milan, (1969) 1974); Nunzio Pernicone, Italian Anarchism 1864–1892 (Princeton, 1993); Renato Zangheri, Storia del socialismo italiano. -

SAR M. Le Mouvement Anarchiste En Espagne. Pouvoir Et RÉ

502 Book reviews Lorenzo, Ce´sar M. Le mouvement anarchiste en Espagne. Pouvoir et re´volution sociale. Les E´ ditions Libertaires, S.l. 2006. 559 pp. A 35.00. DOI: S0020859007023267 This is a revised, updated, and considerably expanded edition of a study which first appeared in 1969. The bulk of it is divided into four parts, which provide a more or less chronological account. Part 1 covers the rise of a libertarian workers’ movement, analysing its ideological foundations, and tracing its development from the September Revolution of 1868 to the CNT’s Saragossa conference of May 1936. Part 2 provides a ‘‘panorama’’ of the revolution of July 1936, each chapter analysing the revolutionary political structures thrown up in different parts of the country, and the role played within them by the CNT. Part 3 concentrates on ‘‘the civil war within the civil war’’, from the autumn of 1936 through the counter-revolution of May 1937 to the CNT’s relations with the Negrin government; it also examines the strengths and weaknesses of the collectivizations (still a seriously under-researched area). The shorter Part 4 analyses what the author calls the ‘‘period of decadence and retreat’’ from the defeat of 1939 through to the experience of exile and the divisions of the post-Franco era. In a thirty-seven-page ‘‘appendix’’, Lorenzo addresses critically the various more or less dubious attempts to explain why there has been, as the French anarchist Louis Lecoin once put it, ‘‘no other country where Anarchism has put down such deep roots as in Spain’’.1 Whilst rejecting what he bluntly dismisses as ‘‘racist’’ attempts at explanation and praising the work of some Marxist historians (Pierre Vilar, notably), Lorenzo goes on to analyse Spanish culture and the set of values and attitudes which, he argues, left their mark on what would become a distinctively Spanish anarchism. -

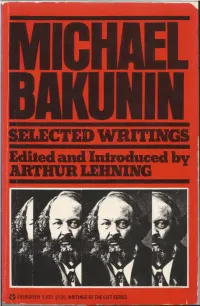

^ CTEP WRITINGS Edited and Introduced Bv ARTHUR LEHNING

IGHAEL ^■ CTEP WRITINGS Edited and Introduced bv ARTHUR LEHNING ^ EVERGREEN E-629 $4.95 WRITINGS OF THE LEFT SERIES WRITINGS OF THE LEFT General Editor: ralph miliband Professor o f Politics at Leeds University MICHAEL BAKUNIN SELECTED WRITINGS MICHAEL BAKUNIN SELECTED WRITINGS Edited and Introduced by ARTHUR LEHNING Editor Archives Bakounine, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam Translations from the French by STEVEN cox Translations from the Russian by OLIVE STEVENS JONATHAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON THIS COMPILATION FIRST PUBLISHED 1973 INTRODUCTION AND COMPILATION © 1973 BY ARTHUR LEHNING TRANSLATIONS BY STEVEN COX AND OLIVE STEVENS © 1973 BY JONATHAN CAPE LTD JONATHAN CAPE LTD, 30 BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON WCI Hardback edition isb n o 224 00893 5 Paperback edition isb n o 224 00898 6 Condition o f Sale This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated with out the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition in cluding this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY EBENEZER BAYLIS AND SON LTD THE TRINITY PRESS, WORCESTER AND LONDON GENERAL EDITOR’S PREFACE It is often claimed nowadays that terms like Left and Right have ceased to mean very much. This is not true: the distinc tion endures, in as sharp a form as ever, between those who, on the one hand, accept as given the framework, if not all the features, of capitalist society; and those who, on the other, are concerned with and work for the establishment of a socialist alternative to the here and now. -

Alberto Corsín Jiménez

CHAPTER FOUR AUTONOMIA ETHNOGRAPHICA Liberal Designs, Designs for Liberation, and the Liberation of Design Alberto Corsín Jiménez This chapter develops an argument about the relation between autonomy and ethnography—in particular, about autonomy as an experimental design in political and anthropological praxis. I am interested in what I call autonomia ethnographica: the pressures and challenges confronting the mise-en-scénes of anthropological fieldwork today and the sometimes troubled, sometimes conflictive, yet ultimately liberating arrangements in complicity and complexity through which anthropologists construct the conditions for ethnographic practice and description. The concept of autonomy I am summoning here needs a little unpacking. In some respects, autonomy is undergoing somewhat of a comeback in social and political theory (Nelson and Braun 2017; Luisetti et al. 2015). Most famously deployed by the Italian operaist (workers) movement in the 1950s in the context of accelerating and exploitative labor conditions in the automobile industry, “autonomia” was invoked at the time to describe a revolutionary impulse for the ontological self-determination of workers’ power—the power, as it was referred to at the time, to “refuse to work” (Virno 1996) and in this capacity to disengage from, and invent novel imaginative alternatives to, the spatial and temporal matrices of the state-capital nexus (Aureli 2008). Throughout the 1970s, however, “autonomia” gradually lost its attachment to workers’ power, leaving the factory floor for the street protests of students, feminists, and environmental activists. Thus, a second generation of “diffuse autonomy” was born, a new wave of insurrectional and intersectional politics (Cuninghame 2013), which, in the wake of the alter- globalization movement in the late 1990s, entered also the Anglophone academy under the 1 liberation aesthetics of networked-mediated multitudes and commons (Hardt and Negri 2005; 2009). -

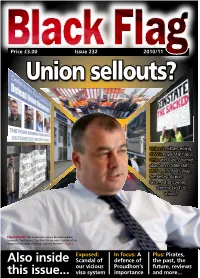

Also Inside This Issue

PricePrice £3.00 £3.00 IssueIssue 232 229 Mid 2010/11 2009 Union sellouts? Unison’s militant exiling, CWU’s Royal Mail fiasco, Unite and Gate Gourmet, abandoned Mitie staff, NUT and St Paul’s Way, the Belfast Airport farce... what’s wrong with the big TUC unions? Figurehead: TUC general secretary Brendan Barber lambasts “bad bosses,” but do the member unions of his organisation really stand up when it matters? Page 7 Exposed: In focus: A Plus: Pirates, Also inside Scandal of defence of the past, the our vicious Proudhon’s future, reviews this issue... visa system importance and more... Editorial Welcome to issue 232 of Black Flag, which coincides once again with the annual London Anarchist Bookfair, the largest and longest-running event of its kind in the world. Now that this issue is the 7th published by the “new” collective we can safely drop the “new” bit! We believe that we have come a long way with Black Flag. As a very small collective we have managed to publish and sustain a consistent and high-quality, twice yearly, class- struggle anarchist publication on a shoe-string budget and limited personnel. Before proceeding further, we would like to make our usual appeal for more people to get involved with the editorial group. The more people who get involved, the more Black Flag will grow with increased frequency and wider distribution etc. This issue includes our usual eclectic mix of libertarian-left theory, history, debate, analysis and reportage. Additionally, this issue is again somewhat of an anniversary issue, which acknowledges two significant events. -

Karl Marx and the Iwma Revisited 299 Jürgen Herres

“Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth” <UN> Studies in Global Social History Editor Marcel van der Linden (International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Editorial Board Sven Beckert (Harvard University, Cambridge, ma, usa) Dirk Hoerder (University of Arizona, Phoenix, ar, usa) Chitra Joshi (Indraprastha College, Delhi University, India) Amarjit Kaur (University of New England, Armidale, Australia) Barbara Weinstein (New York University, New York, ny, usa) volume 29 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/sgsh <UN> “Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth” The First International in a Global Perspective Edited by Fabrice Bensimon Quentin Deluermoz Jeanne Moisand leiden | boston <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Cover illustration: Bannière de la Solidarité de Fayt (cover and back). Sources: Cornet Fidèle and Massart Théophile entries in Dictionnaire biographique du mouvement ouvrier en Belgique en ligne : maitron-en -ligne.univ-paris1.fr. Copyright : Bibliothèque et Archives de l’IEV – Brussels. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bensimon, Fabrice, editor. | Deluermoz, Quentin, editor. | Moisand, Jeanne, 1978- editor. Title: “Arise ye wretched of the earth” : the First International in a global perspective / edited by Fabrice Bensimon, Quentin Deluermoz, Jeanne Moisand. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2018] | Series: Studies in global social history, issn 1874-6705 ; volume 29 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018002194 (print) | LCCN 2018004158 (ebook) | isbn 9789004335462 (E-book) | isbn 9789004335455 (hardback : alk. -

Ukraine, L9l8-21 and Spain, 1936-39: a Comparison of Armed Anarchist Struggles in Europe

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Fall 2020 Ukraine, l9l8-21 and Spain, 1936-39: A Comparison of Armed Anarchist Struggles in Europe Daniel A. Collins Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Collins, Daniel A., "Ukraine, l9l8-21 and Spain, 1936-39: A Comparison of Armed Anarchist Struggles in Europe" (2020). Honors Theses. 553. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/553 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ukraine, 1918-21 and Spain, 1936-39: A Comparison of Armed Anarchist Struggles in Europe by Daniel A. Collins An Honors Thesis Submitted to the Honors Council For Honors in History 12/7/2020 Approved by: Adviser:_____________________________ David Del Testa Second Evaluator: _____________________ Mehmet Dosemeci iii Acknowledgements Above all others I want to thank Professor David Del Testa. From my first oddly specific question about the Austro-Hungarians on the Italian front in my first week of undergraduate, to here, three and a half years later, Professor Del Testa has been involved in all of the work I am proud of. From lectures in Coleman Hall to the Somme battlefield, Professor Del Testa has guided me on my journey to explore World War I and the Interwar Period, which rapidly became my topics of choice. -

Anarchism : a History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements

Anarchism : A History Of Libertarian Ideas And Movements GEORGE WOODCOCK Meridian Books The World Publishing Company Cleveland and New York -3- AN ORIGINAL MERIDIAN BOOK Published by The World Publishing Company 2231 West 110th Street, Cleveland 2, Ohio First printing March 1962 CP362 Copyright © 1962 by The World Publishing Company All rights reserved Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 62-12355 Printed in the United States of America -4- AN ORIGINAL MERIDIAN BOOK Published by The World Publishing Company 2231 West 110th Street, Cleveland 2, Ohio First printing March 1962 CP362 Copyright © 1962 by The World Publishing Company All rights reserved Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 62-12355 Printed in the United States of America -4- Contents 1. PROLOGUE 9 I. The Idea 2. THE FAMILY TREE 37 3. THE MAN OF REASON 60 4. THE EGOIST 94 5. THE MAN OF PARADOX 106 6. THE DESTRUCTIVE URGE 145 7. THE EXPLORER 184 8. THE PROPHET 222 II. The Movement 9. INTERNATIONAL ENDEAVORS 239 10. ANARCHISM IN FRANCE 275 11. ANARCHISM IN ITALY 327 12. ANARCHISM IN SPAIN 356 -5- 13. ANARCHISM IN RUSSIA 399 14. VARIOUS TRADITIONS: ANARCHISM IN LATIN AMERICA, NORTHERN EUROPE, BRITAIN, AND THE UNITED STATES 425 15. EPILOGUE 468 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 479 INDEX 491 -6- Anarchism A HISTORY OF LIBERTARIAN IDEAS AND MOVEMENTS -7- [This page intentionally left blank.] -8- I. Prologue "Whoever denies authority and fights against it is an anarchist," said Sébastien Faure. The definition is tempting in its simplicity, but simplicity is the first thing to guard against in writing a history of anarchism. -

Italian Anarchists in London (1870-1914)

1 ITALIAN ANARCHISTS IN LONDON (1870-1914) Submitted for the Degree of PhD Pietro Dipaola Department of Politics Goldsmiths College University of London April 2004 2 Abstract This thesis is a study of the colony of Italian anarchists who found refuge in London in the years between the Paris Commune and the outbreak of the First World War. The first chapter is an introduction to the sources and to the main problems analysed. The second chapter reconstructs the settlement of the Italian anarchists in London and their relationship with the colony of Italian emigrants. Chapter three deals with the activities that the Italian anarchists organised in London, such as demonstrations, conferences, and meetings. It likewise examines the ideological differences that characterised the two main groups in which the anarchists were divided: organisationalists and anti-organisationalists. Italian authorities were extremely concerned about the danger represented by the anarchists. The fourth chapter of the thesis provides a detailed investigation of the surveillance of the anarchists that the Italian embassy and the Italian Minster of Interior organised in London by using spies and informers. At the same time, it describes the contradictory attitude held by British police forces toward political refugees. The following two chapters are dedicated to the analysis of the main instruments of propaganda used by the Italian anarchists: chapter five reviews the newspapers they published in those years, and chapter six reconstructs social and political activities that were organised in their clubs. Chapter seven examines the impact that the outbreak of First World Word had on the anarchist movement, particularly in dividing it between interventionists and anti- interventionists; a split that destroyed the network of international solidarity that had been hitherto the core of the experience of political exile. -

Passage to Mode ... France Italy and Spain.Pdf

Working Paper — Comments Welcome PASSAGE TO MODERNITY: THINKING THEORETICALLY ABOUT THE EXPERIENCE OF FRANCE, ITALY AND SPAIN Filippo Sabetti McGill University [email protected] It is hard to imagine many countries so similar and dissimilar - at times amici/nemici all at once - as France, Italy and Spain. In addition to physical proximity and characteristics, they share common linguistic and cultural roots, have for the most part genuflected at the same altar, and assimilated, emulated and, at times, sought to avoid each another's customs, institutions and ways of life. The movement of ideas, people and goods between them, seldom severed for long, proceeded over the centuries through mutual consent, rivalry, imitation, alliance, dynastic or territorial aggrandizement and force. The network of relations became more fixed, but no less complex to understand, with the Enlightenment, the French Revolution and their respective reverberations. Just consider. A Neapolitan Bourbon monarch and Neapolitan advisers in the eighteenth century helped to make Spain a nation state, but it was Napoleon's brother who was truly the first king of Spain. Before becoming king of France in 1830, Louis Philippe sat as a peer in the Sicilian parliament. The Spaniards fought against the Napoleonic state being created in France and Italy but undertook to create a more centralized and more egalitarian constitutional arrangement of their own in 1812, in the process giving the world the term "liberal" and setting a precedent for modern military intervention in constitutional and institutional reforms (the so called pronunciamientos) that was to afflict Spanish public life until the Franco regime.