The Italians and the Iwma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Heather Marlene Bennett University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Heather Marlene, "Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 734. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Abstract The traumatic legacies of the Paris Commune and its harsh suppression in 1871 had a significant impact on the identities and voter outreach efforts of each of the chief political blocs of the 1870s. The political and cultural developments of this phenomenal decade, which is frequently mislabeled as calm and stable, established the Republic's longevity and set its character. Yet the Commune's legacies have never been comprehensively examined in a way that synthesizes their political and cultural effects. This dissertation offers a compelling perspective of the 1870s through qualitative and quantitative analyses of the influence of these legacies, using sources as diverse as parliamentary debates, visual media, and scribbled sedition on city walls, to explicate the decade's most important political and cultural moments, their origins, and their impact. -

The Socialist Minority and the Paris Commune of 1871 a Unique Episode in the History of Class Struggles

THE SOCIALIST MINORITY AND THE PARIS COMMUNE OF 1871 A UNIQUE EPISODE IN THE HISTORY OF CLASS STRUGGLES by PETER LEE THOMSON NICKEL B.A.(Honours), The University of British Columbia, 1999 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of History) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2001 © Peter Lee Thomson Nickel, 2001 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Hi'sio*" y The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date AkgaS-f 30. ZOO I DE-6 (2/88) Abstract The Paris Commune of 1871 lasted only seventy-two days. Yet, hundreds of historians continue to revisit this complex event. The initial association of the 1871 Commune with the first modern socialist government in the world has fuelled enduring ideological debates. However, most historians past and present have fallen into the trap of assessing the Paris Commune by foreign ideological constructs. During the Cold War, leftist and conservative historians alike overlooked important socialist measures discussed and implemented by this first- ever predominantly working-class government. -

The State and Revolution: Theory and Practice Contents

The State and Revolution: Theory and Practice Iain McKay This is almost my chapter in the anthology Bloodstained: One Hundred Years of Leninist Counterrrevolution (Oakland/Edinburgh: AK Press, 2017). Some revisions were made during the editing process which are not included here. In addition, references to the 1913 French edition of Kropotkin’s Modern Science and Anarchy have been replaced with those from the 2018 English-language translation. However, the bulk of the text is the same, as is the message and its call to learn from history rather than repeat it. I would, of course, urge you to buy the book. Contents The State and Revolution: Theory and Practice ......................................................... 2 Theory .................................................................................................................... 2 The Paris Commune ........................................................................................... 4 Opportunism ....................................................................................................... 7 Anarchism ......................................................................................................... 10 Socialism ........................................................................................................... 18 The Party .......................................................................................................... 20 Practice ................................................................................................................ -

'The Italians and the IWMA'

Levy, Carl. 2018. ’The Italians and the IWMA’. In: , ed. ”Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth”. The First International in Global Perspective. 29 The Hague: Brill, pp. 207-220. ISBN 978-900-4335-455 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/23423/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] chapter �3 The Italians and the iwma Carl Levy Introduction Italians played a significant and multi-dimensional role in the birth, evolution and death of the First International, and indeed in its multifarious afterlives: the International Working Men's Association (iwma) has also served as a milestone or foundation event for histories of Italian anarchism, syndicalism, socialism and communism.1 The Italian presence was felt simultaneously at the national, international and transnational levels from 1864 onwards. In this chapter I will first present a brief synoptic overview of the history of the iwma (in its varied forms) in Italy and abroad from 1864 to 1881. I will then exam- ine interpretations of aspects of Italian Internationalism: Mazzinian Repub- licanism and the origins of anarchism, the Italians, Bakunin and interactions with Marx and his ideas, the theory and practice of propaganda by the deed and the rise of a third-way socialism neither fully reformist nor revolutionary, neither Marxist nor anarchist. -

Socialism in Europe and the Russian Revolution India and the Contemporary World Society Ofthefuture

Socialism in Europe and II the Russian Revolution Chapter 1 The Age of Social Change In the previous chapter you read about the powerful ideas of freedom and equality that circulated in Europe after the French Revolution. The French Revolution opened up the possibility of creating a dramatic change in the way in which society was structured. As you have read, before the eighteenth century society was broadly divided into estates and orders and it was the aristocracy and church which controlled economic and social power. Suddenly, after the revolution, it seemed possible to change this. In many parts of the world including Europe and Asia, new ideas about individual rights and who olution controlled social power began to be discussed. In India, Raja v Rammohan Roy and Derozio talked of the significance of the French Revolution, and many others debated the ideas of post-revolutionary Europe. The developments in the colonies, in turn, reshaped these ideas of societal change. ian Re ss Not everyone in Europe, however, wanted a complete transformation of society. Responses varied from those who accepted that some change was necessary but wished for a gradual shift, to those who wanted to restructure society radically. Some were ‘conservatives’, others were ‘liberals’ or ‘radicals’. What did these terms really mean in the context of the time? What separated these strands of politics and what linked them together? We must remember that these terms do not mean the same thing in all contexts or at all times. We will look briefly at some of the important political traditions of the nineteenth century, and see how they influenced change. -

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939 Sam Dolgoff (editor) 1974 Contents Preface 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introductory Essay by Murray Bookchin 9 Part One: Background 28 Chapter 1: The Spanish Revolution 30 The Two Revolutions by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 30 The Bolshevik Revolution vs The Russian Social Revolution . 35 The Trend Towards Workers’ Self-Management by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 36 Chapter 2: The Libertarian Tradition 41 Introduction ............................................ 41 The Rural Collectivist Tradition by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 41 The Anarchist Influence by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 44 The Political and Economic Organization of Society by Isaac Puente ....................................... 46 Chapter 3: Historical Notes 52 The Prologue to Revolution by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 52 On Anarchist Communism ................................. 55 On Anarcho-Syndicalism .................................. 55 The Counter-Revolution and the Destruction of the Collectives by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 56 Chapter 4: The Limitations of the Revolution 63 Introduction ............................................ 63 2 The Limitations of the Revolution by Gaston Leval ....................................... 63 Part Two: The Social Revolution 72 Chapter 5: The Economics of Revolution 74 Introduction ........................................... -

Levy, Carl. 2017. Malatesta and the War Interventionist Debate 1914-1917: from the ’Red Week’ to the Russian Revolutions

Levy, Carl. 2017. Malatesta and the War Interventionist Debate 1914-1917: from the ’Red Week’ to the Russian Revolutions. In: Matthew S. Adams and Ruth Kinna, eds. Anarchism, 1914-1918: Internationalism, Anti-Militarism and War. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 69-92. ISBN 9781784993412 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/20790/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] 85 3 Malatesta and the war interventionist debate 1914–17: from the ‘Red Week’ to the Russian revolutions Carl Levy This chapter will examine Errico Malatesta’s (1853–1932) position on intervention in the First World War. The background to the debate is the anti-militarist and anti-dynastic uprising which occurred in Italy in June 1914 (La Settimana Rossa) in which Malatesta was a key actor. But with the events of July and August 1914, the alliance of socialists, republicans, syndicalists and anarchists was rent asunder in Italy as elements of this coalition supported intervention on the side of the Entente and the disavowal of Italy’s treaty obligations under the Triple Alliance. Malatesta’s dispute with Kropotkin provides a focus for the anti-interventionist campaigns he fought internationally, in London and in Italy.1 This chapter will conclude by examining Malatesta’s discussions of the unintended outcomes of world war and the challenges and opportunities that the fracturing of the antebellum world posed for the international anarchist movement. -

SAR M. Le Mouvement Anarchiste En Espagne. Pouvoir Et RÉ

502 Book reviews Lorenzo, Ce´sar M. Le mouvement anarchiste en Espagne. Pouvoir et re´volution sociale. Les E´ ditions Libertaires, S.l. 2006. 559 pp. A 35.00. DOI: S0020859007023267 This is a revised, updated, and considerably expanded edition of a study which first appeared in 1969. The bulk of it is divided into four parts, which provide a more or less chronological account. Part 1 covers the rise of a libertarian workers’ movement, analysing its ideological foundations, and tracing its development from the September Revolution of 1868 to the CNT’s Saragossa conference of May 1936. Part 2 provides a ‘‘panorama’’ of the revolution of July 1936, each chapter analysing the revolutionary political structures thrown up in different parts of the country, and the role played within them by the CNT. Part 3 concentrates on ‘‘the civil war within the civil war’’, from the autumn of 1936 through the counter-revolution of May 1937 to the CNT’s relations with the Negrin government; it also examines the strengths and weaknesses of the collectivizations (still a seriously under-researched area). The shorter Part 4 analyses what the author calls the ‘‘period of decadence and retreat’’ from the defeat of 1939 through to the experience of exile and the divisions of the post-Franco era. In a thirty-seven-page ‘‘appendix’’, Lorenzo addresses critically the various more or less dubious attempts to explain why there has been, as the French anarchist Louis Lecoin once put it, ‘‘no other country where Anarchism has put down such deep roots as in Spain’’.1 Whilst rejecting what he bluntly dismisses as ‘‘racist’’ attempts at explanation and praising the work of some Marxist historians (Pierre Vilar, notably), Lorenzo goes on to analyse Spanish culture and the set of values and attitudes which, he argues, left their mark on what would become a distinctively Spanish anarchism. -

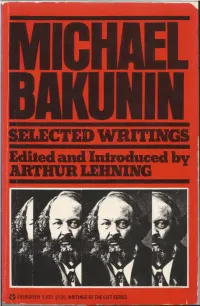

^ CTEP WRITINGS Edited and Introduced Bv ARTHUR LEHNING

IGHAEL ^■ CTEP WRITINGS Edited and Introduced bv ARTHUR LEHNING ^ EVERGREEN E-629 $4.95 WRITINGS OF THE LEFT SERIES WRITINGS OF THE LEFT General Editor: ralph miliband Professor o f Politics at Leeds University MICHAEL BAKUNIN SELECTED WRITINGS MICHAEL BAKUNIN SELECTED WRITINGS Edited and Introduced by ARTHUR LEHNING Editor Archives Bakounine, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam Translations from the French by STEVEN cox Translations from the Russian by OLIVE STEVENS JONATHAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON THIS COMPILATION FIRST PUBLISHED 1973 INTRODUCTION AND COMPILATION © 1973 BY ARTHUR LEHNING TRANSLATIONS BY STEVEN COX AND OLIVE STEVENS © 1973 BY JONATHAN CAPE LTD JONATHAN CAPE LTD, 30 BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON WCI Hardback edition isb n o 224 00893 5 Paperback edition isb n o 224 00898 6 Condition o f Sale This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated with out the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition in cluding this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY EBENEZER BAYLIS AND SON LTD THE TRINITY PRESS, WORCESTER AND LONDON GENERAL EDITOR’S PREFACE It is often claimed nowadays that terms like Left and Right have ceased to mean very much. This is not true: the distinc tion endures, in as sharp a form as ever, between those who, on the one hand, accept as given the framework, if not all the features, of capitalist society; and those who, on the other, are concerned with and work for the establishment of a socialist alternative to the here and now. -

The Italian Communist Party 1921--1964: a Profile

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1966 The Italian Communist Party 1921--1964: A profile. Aldo U. Marchini University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Marchini, Aldo U., "The Italian Communist Party 1921--1964: A profile." (1966). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6438. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6438 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript and are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was scanned as received. it This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE ITALIAN COkkUNIST PARTY 1921 - 196A: A PROPILE by ALDO U. -

Finding Aid Prepared by David Kennaly Washington, D.C

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISION THE RADICAL PAMPHLET COLLECTION Finding aid prepared by David Kennaly Washington, D.C. - Library of Congress - 1995 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK ANtI SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISIONS RADICAL PAMPHLET COLLECTIONS The Radical Pamphlet Collection was acquired by the Library of Congress through purchase and exchange between 1977—81. Linear feet of shelf space occupied: 25 Number of items: Approx: 3465 Scope and Contents Note The Radical Pamphlet Collection spans the years 1870-1980 but is especially rich in the 1930-49 period. The collection includes pamphlets, newspapers, periodicals, broadsides, posters, cartoons, sheet music, and prints relating primarily to American communism, socialism, and anarchism. The largest part deals with the operations of the Communist Party, USA (CPUSA), its members, and various “front” organizations. Pamphlets chronicle the early development of the Party; the factional disputes of the 1920s between the Fosterites and the Lovestoneites; the Stalinization of the Party; the Popular Front; the united front against fascism; and the government investigation of the Communist Party in the post-World War Two period. Many of the pamphlets relate to the unsuccessful presidential campaigns of CP leaders Earl Browder and William Z. Foster. Earl Browder, party leader be—tween 1929—46, ran for President in 1936, 1940 and 1944; William Z. Foster, party leader between 1923—29, ran for President in 1928 and 1932. Pamphlets written by Browder and Foster in the l930s exemplify the Party’s desire to recruit the unemployed during the Great Depression by emphasizing social welfare programs and an isolationist foreign policy. -

Anarchism and the State in Portugal (1890-1911): a Preliminary Approach’

Diogo DUARTE, ‘Anarchism and the State in Portugal (1890-1911): A preliminary approach’ I could not start without thanking the invitation for me to be present here, in particular to Professor David Berry and the Anarchism Research Group. It’s a particularly generous invitation, since what I intend to present here is part of an ongoing work for my doctorate thesis, which is still in a phase that can be considered initial. As such, my presence here and the opportunity to share this work and these ideas with all of you is especially exciting for me, as I may benefit from your commentary, critique and questions. This is why I am particularly grateful for this opportunity. As the title of my talk indicates, I don’t intend to look solely at anarchism, or to anarchism in itself, but to insert it in a broader context and set of relations that marked it in a period of Portuguese history in which anarchism registered a very significant presence, especially due to its influence in the midst of the working class in the big cities, as well as in some intellectual circles. I don’t know if you are familiar with the history of anarchism in Portugal, or even with the dimension of that presence – a presence which may be compared, with no exaggeration, to that which was registered in Spain during the same period –, however, assuming that the majority isn’t familiar, during the course of this presentation I will attempt to briefly introduce a few aspects of the history of anarchism in Portugal, or accompany some of the ideas that I want to share here with commentary that may aid in explaining some aspects of that history.