The Etymologic Structure of Romanian Mythonyms (Ii)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Modern Bulgarian Literature

The History ol , v:i IL Illlllf iM %.m:.:A Iiiil,;l|iBif| M283h UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES COLLEGE LIBRARY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/historyofmodernbOOmann Modern Bulgarian Literature The History of Modern Bulgarian Literature by CLARENCE A. MANNING and ROMAN SMAL-STOCKI BOOKMAN ASSOCIATES :: New York Copyright © 1960 by Bookman Associates Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 60-8549 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY UNITED PRINTING SERVICES, INC. NEW HAVEN, CONN. Foreword This outline of modern Bulgarian literature is the result of an exchange of memories of Bulgaria between the authors some years ago in New York. We both have visited Bulgaria many times, we have had many personal friends among its scholars and statesmen, and we feel a deep sympathy for the tragic plight of this long-suffering Slavic nation with its industrious and hard-working people. We both feel also that it is an injustice to Bulgaria and a loss to American Slavic scholarship that, in spite of the importance of Bulgaria for the Slavic world, so little attention is paid to the country's cultural contributions. This is the more deplorable for American influence in Bulgaria was great, even before World War I. Many Bulgarians were educated in Robert Col- lege in Constantinople and after World War I in the American College in Sofia, one of the institutions supported by the Near East Foundation. Many Bulgarian professors have visited the United States in happier times. So it seems unfair that Ameri- cans and American universities have ignored so completely the development of the Bulgarian genius and culture during the past century. -

Úvod ...4. 1 . Slované ...7. 2. Rozdělení Bohů

Obsah: Úvod . 4. 1. Slované . 7. 1.1 Příchod Slovanů . 7. 1.1 Slované a jejich víra v božstvo ( polyteizmus) . 7. 1.2 Kult uctívání božstva . 9. 2. Rozdělení bohů podle významu lidstva . 11. 2.1 Hlavní bohové . 11. Svarog . 12. Svarožic – Dažbog. 12. Perun . 12. Veles . 13. 2.2 Ruský okruh – bohové východních Slovanů. 14. Stribog . 15. Chors . 15. Simargl . 15. Mokoš . 16. Trojan . 16. 2.3 Polabsko pobaltský okruh – západní Slované . 17. Svarožic – Radogost . 17. Svantovít . 18. Triglav . 19. 2.4 Další božstvo uctívané Polabany a Pobalťany . 20. Prove . 20. Podala . 20. Živa . 20. Černoboh . 20. Pripegala . 20. 1 Rugievit . 21. Polevit . 21. Porenutius . 21. Gerovit . 21. Morana . 21. 2.5 Nepodložení bohové . 22. Lada . 22. Baba . 22. Děvana . 22. 3. Duchovno starých Slovanů . 23. 3.1 Kult uctívání zvířat, rostlin a věcí . 23. 3.2 Oslavy roku . 23. 3.3 Duchové a démoni . 24. 3.4 Lesní bytosti . 26. 3.5 Polní bytosti . 27. 3.6 Duchové času . 27. 4. Báje, balady, pověsti a pověry . 28. 4.1 Báje o Svarogovi . 28. 4.2 Báje o Svarožicovi . 28. 4.3 Báje o Radegastovi . 29. 4.4 Zrození Dažboga . 30. 4.5 Mokoš . 31. 4.6 Balady – Polednice, Vodník (Karel Jaromír Erben) . 33. 4.7 Pověry – Světlonoši, Zlatobaba . 36. 5. Vlastní tvorba . 39. 5.1 Zobrazování božstva . 39. 2 5.2 Pohled na svět Slovanských Bohů ve výtvarné výchově . 40. 5.3 Vlastní tvorba . 41. 6. Slovanství a Bohové očima dnešních umělců . 44. 6.1 Jak vidí Slovanské bohy Oldřich Unar . 44. 6.2 Smysl Slovanství pro Lojzu Baránka . -

CAC 4 Grupa 01 FCI 15 Chien De Berger Belge

Nr.start Numele cainelui / Name COR Data nast./D.o.b. CAC 4 Grupa 01 F.C.I. 15 Chien de berger belge - Tervueren Campioni / Champion Femele/Bitches 9 BLACK CARAMBAS AQUA FI50644\/13 20/09/2013 Heracles Of The Home Port && Ce Demetra Av Nangijala Cr/B: Sonja Enlund Pr/O: Siru Heinonen SF F.C.I. 332 Ceskoslovensky Vlcak Pui / Puppy Masculi/Dogs 10 O'TARIS MALY BYSTEREC LO1795122 16/12/2016 Gunner Maly Bysterec && Connie Vlci Tlapka Cr/B: Marek Medvecky Pr/O: Motta Stefania I Campioni / Champion Masculi/Dogs 11 CHARON SRDCERVAC COR A 264-15\/332 06/12/2014 CHEWBE && ANNE LEE SRDCERVAC Cr/B: DANIELA CILOVA Pr/O: FOCK RODICA RO 12 DEVIL MAVERICK LOI11\/33252 01/01/2011 Wakan Arimminum && Ch. Ombra Passo de Lupo Cr/B: Bonfiglioli Alessandra Pr/O: Degli Esposti Barbara I Juniori / Junior Femele/Bitches 13 WINDESPRESS MIRAGE LOI16178231 26/08/2016 Ch. Devil Maverick && Kyra Cr/B: Pacifici Mauro Pr/O: Degli Esposti Barbara I Campioni / Champion Femele/Bitches 14 FOLLIA DEI LUPI DI GUBBIO LO1416139 07/11/2013 Induk PDL && Chakra di Gubbio Cr/B: Masci Germano Pr/O: Stefania Motta I Munca / Working Femele/Bitches 15 ATHENA SHADOW OF THE PHOENIX RSR 14\/29729 25/12/2013 Zenith Od Uhoste && Nan\u00e0 di Villa Doria Cr/B: Alessia Pasquali Pr/O: Alessia Pasquali I F.C.I. 166 Deutscher Schaferhund Short-haired Baby / Baby Masculi/Dogs 16 HANNO AV THORARINN NO45151\/17 30/04/2017 Hugh Vom Eichenplatz && Ugana Av Thorarinn Cr/B: Hamgaard Per Pr/O: Paivi Pulkkinen SF Juniori / Junior Masculi/Dogs 17 SCHULTZ VON BISTRITZ A 30998-16\/166 25/09/2016 GERO VON -

45 Natalya GOLANT MYTHOLOGICAL IDEAS of VLACHS of EASTERN

ЖУРНАЛ ЭТНОЛОГИИ И КУЛЬТУРОЛОГИИ Том XVIII 45 oficiale a timpului. Ключевые слова: А. А. Скальковский, историо- Cuvinte-cheie: A. A. Skalkovsky, istoriografie, Novo- графия, Новороссия, Бессарабия, краеведение. rosye, Basarabia, studii regionale. Summary Резюме The article deals with the contribution of Apollon В статье рассматривается вклад известного ис- Skalkovsky (1808–1898), the outstanding researcher of следователя юга России XIX в. Аполлона Александро- Southern Russia in the XIXth century, to historical stud- вича Скальковского, оставившего яркий след в деле ies of Novorossiya and Bessarabia in trarist Russia. His- изучения истории новороссийских земель и Бессара- toriographical analysis of this scholar’s works represents бии периода царской России. Историографический groundwork in the field of historical heritage as well as анализ трудов ученого представляет собой широкий demography, statistics and ethnography, a scientific direc- спектр его наработок не только в области истори- tion that was making its first steps, the area of Southern ческого наследия, но и в демографии, статистике, а Russia being of peculiar interest from the point of view of также в зарождающейся этнографической науке, для the official historiography. которой земли южной России представляли особый Key words: A. Skalkovsky, historiography, Novoros- интерес с точки зрения официальной историографии siya, historiography, area studies. того времени. Natalya GOLANT MYTHOLOGICAL IDEAS OF VLACHS OF EASTERN SERBIA (BASED ON MATERIALS OF EXPEDITIONS OF 2013–2014) This -

Velimir Chlebnikov 1885-1985

Sagners Slavistische Sammlung ∙ Band 11 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Johannes Holthusen, Johanna Renata Döring-Smirnov, Walter Koschmal, Peter Stobbe (Hrsg.) Velimir Chlebnikov 1885-1985 Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein ImprintJohannes Holthusen,der Kubon Johanna & SagnerRenata Döring-Smirnov GmbH. and Walter Koschmal - 9783954790135 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:42:39AM via free access SAGNERS SLAVISTICHE SAMMLUNG herausgegeben von PETER REHDER Band 11 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER München 1986 Johannes Holthusen, Johanna Renata Döring-Smirnov and Walter Koschmal - 9783954790135 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:42:39AM via free access C h l e b n ik o V o k in b e l h C E L I M I 1985 R 1885 Herausgegeben von J. Holthusen f J. R. Döring-Smimov • W. Koschmal • P. Stobbe VERLAG OTTO SAGNER München 1986 Johannes Holthusen, Johanna Renata Döring-Smirnov and Walter Koschmal - 9783954790135 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:42:39AM via free access Bayerische cSlBatsb i b 1 iottylK L »MftöftW1 J ISBN 3-87690-3300 С by Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1986 Johannes Holthusen, Johanna Renata Döring-Smirnov and Walter Koschmal - 9783954790135 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:42:39AM via free access Johannes Holthusen, Johanna Renata Döring-Smirnov and Walter Koschmal - 9783954790135 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:42:39AM via free access Johannes Holthusen, Johanna Renata Döring-Smirnov and Walter Koschmal - 9783954790135 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:42:39AM via free access Ge l e i t w o r t Aus Anlaß des 100. -

Univerza V Mariboru Filozofska Fakulteta

UNIVERZA V MARIBORU FILOZOFSKA FAKULTETA ODDELEK ZA SOCIOLOGIJO DIPLOMSKO DELO Sara Gabrič Januar, 2010 UNIVERZA V MARIBORU FILOZOFSKA FAKULTETA ODDELEK ZA SOCIOLOGIJO Diplomsko delo ŢENSKI LIKI V SLOVANSKI MITOLOGIJI Mentor: Kandidatka: red. prof. dr. Sergej Flere Sara Gabrič Maribor, 2010 Lektorica: Bojana Kovačič Zemljič, uni. dipl. prof. slo. jezika. Prevajalka: Danijela Kačinari, prof. ang. jezika ZAHVALA Posebna zahvala gre mentorju dr. Sergeju Flereju, tako za njegovo zavzeto delo pri usmerjanju in svetovanju, kakor tudi za njegove konstruktivne kritike, ki so spodbudile moje nadaljnjo razmišljanje in me prisilile k iskanju novih rešitev. Rada bi se zahvalila prijateljem in sorodnikom, ki so me vzpodbujali in mi svetovali ter mi pomagali pri iskanju literature. Najbolj pa se zahvaljujem mami in fantu za moralno podporo in spodbujanje, tako v času študija kot ob pisanju diplomskega dela. IZJAVA O AVTORSTVU Podpisana Sara Gabrič, roj. 14. 03. 1983, študentka Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Mariboru, smer sociologija in filozofija, izjavljam, da je diplomsko delo z naslovom Ţenski liki v slovanski mitologiji, pri mentorju dr. Sergeju Flereju, avtorsko delo. V diplomskem delu so uporabljeni viri in literatura korektno navedeni; teksti niso prepisani brez navedbe avtorjev. Sara Gabrič Maribor, januar, 2010 POVZETEK V diplomskem delu je obravnavan del bogate slovanske mitologije, in sicer različna ţenska mitološka bitja, ki so jih častili Slovani. Cilj diplomskega dela je spoznati del slovanske mitologije. Vedenje o prvotnem verovanju Slovanov je namreč zelo slabo, več se namreč ve o mitologijah Rimljanov ali Grkov. Diplomsko delo je osredotočeno na predstavitev ţenskih likov v slovanskem verovanju ter pokazati njihov vpliv na vsakdanje ţivljenje Slovanov. Poleg teh boginj so obstajala še druga ţenska mitološka bitja, ki so jih Slovani častili, nekatera celo bolj od samih boginj. -

Marché Du Film Court

COURT MARKET FILM FILM DU SHORT TH MARCHÉ 9 E 2 9 2 INDEX CLERMONT-FERRAND 2014 sommaire / contents Statistiques / Figures 1177 - 1178 CONTENTS Index par Société de production française / Index by French production companies 1179 - 1194 Index général par titre / General index by title 1196 - 1271 SOMMAIRE / Remerciements / Acknowledgements 1272 1177 PAYS PROD. PRINCIPALE ANIM. DOC. EXP. FIC. NB INSC. AU MARCHÉ DURÉE SÉLEC. MOYENNE Afghanistan 5 5 5 13’ Afrique du Sud 3 1 6 10 7 13’ Albanie 2 3 5 5 15’ Algérie 1 2 3 3 20’ 1 Allemagne 70 59 57 221 407 366 14’ 3 Andorre 1 1 1 12’ Argentine 7 7 11 66 91 83 13’ 1 Armenie 4 4 4 18’ 1 Australie 15 17 18 127 177 169 11’ 2 Autriche 11 14 17 28 70 65 13’ 1 Azerbaidjan 2 2 15’ Bahamas 1 1 1 10’ Bahrein 1 2 3 3 7’ Bangladesh 1 2 3 2 10’ Barbade 1 1 1 16’ Belgique 38 20 21 98 177 167 14’ 4 Bénin 1 1 1 13’ Bhoutan 2 2 2 27’ Bielorussie 1 1 2 1 10’ Bolivie 1 1 3 5 5 18’ Bosnie-Herzégovine 2 2 2 6 6 14’ Brésil 17 77 47 169 310 292 14’ 3 Bulgarie 5 2 10 17 16 14’ 1 Burkina Faso 1 3 4 3 8’ Burundi 1 1 1 25’ Cambodge 3 3 3 20’ Cameroun 3 3 2 27’ Canada 29 25 37 121 212 191 11’ 4 Canada, Québec 34 28 33 124 219 218 10’ 1 Cap-Vert 1 1 1 14’ Centrafrique 1 1 1 30’ Chili 3 10 4 14 31 29 17’ Chine 7 7 10 28 52 50 18’ 1 Chine, Hong Kong 2 2 13 17 16 20’ 1 Chypre 2 11 13 13 15’ Colombie 5 5 4 38 52 50 15’ 1 Congo, Rep. -

Demonic Beings with the Romanians of Timoc (Serbia)

BABEŞ-BOLYAI UNIVERSITY CLUJ-NAPOCA FACULTY OF LETTERS DEMONIC BEINGS WITH THE ROMANIANS OF TIMOC (SERBIA) ABSTRACT OF THE PHD DISSERTATION PhD supervisor: PhD candidate: Univ. Proff. Ioan Şeuleanu Annemarie Sorescu-Marinković CLUJ-NAPOCA, 2010 Summary 1. THE ROMANIANS OF TIMOC – AN INTRODUCTION 1.1. Vlachs or Romanians 1.2. Geographical disposal 1.3. The dimension of the community 1.4. Origins 1.5. Spoken language 1.5.1. Ethnographic and dialectal groups and their geographical disposition 1.5.1.2. The mining region of North-Eastern Serbia and the origin of the Bufani 1.6. Conclusions 2. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL STUDIES ON THE FOLK CULTURE OF THE ROMANIANS OF TIMOC 2.1. The first researches on the Timoc Valley – 19th century 2.2. Romanian researches and studies on the folk culture of the Romanians of Timoc 2.2.1. The materialization of this question in Romania 2.2.2. Romanian researchers about Timoc until WWII 2.2.3. The communist period 2.2.4. The period after the Romanian Revolution of 1989 2.3. Researches on the Romanians of Timoc carried out in Serbia 2.3.1. The inter-war period 2.3.2. The period after WWII 2.3.3. Recent researches 2.4. The Romanians of Timoc as seen by foreign researchers 2.5. Sensationalistic texts on the Romanians of Timoc 2.6. Conclusions 3. PECULIARITIES OF FIELD WORK WITH THE ROMANIANS OF TIMOC 3.1. The notion of field 2 3.2. Field research method 3.3. Field research proper with the Romanians of Timoc 3.3.1. -

2 War Against the Witch

2 WAR AGAINST THE WITCH The following pages are dedicated to another mythological theme, a military conflict of androcentric elite with an army led by a witch. Though it is textually subtler, less frequently occurring then the former creation matter, it still seems to be attested among different IE traditions significantly enough to be examined in the field of IE mythological studies. From a certain point of view, it could be seen as a variation on the well-known theme of IE “class conflict”; Indra’s quarrel with Aśvinas, Romans’ war against Sabines etc. However, these narrations will not be reflected. Even though the activ- ity of elite woman can be recognised there, it is neither of central importance nor of a military nature. Besides, they have been already well examined so there is no need to bother with them once again. Instead, in this chapter I intend to deal with the less famous variations on “class conflict” theme, in which the struggle takes the form of battle or war against the forces led by a demonic woman. Nevertheless, in spite of (or thanks to?) the narrowed focus of the chapter, some of its conclusions should be useful for interpretation of the class conflict concept as a whole. The military variation seems to contain several of its basic mo- tives, perhaps only hyperbolised, and so more accessible for further examination, through their highly political conceptualisation. Firstly the theme’s possible mezzo-contextual background will be considered. As the myths in question recount the tale of the quarrel between noble warriors and baseborn rebels led by a female witch, evaluated will be especially processes and structures associated with the identity of androcentric military elites and their attitudes towards the members of marginalised social groups. -

Samodiva (Macedonia/Bulgaria) This Is a Macedonian/Bulgarian Dance Taught by Ventsi Sotirov to This Beautiful Recording by Rayna

Samodiva (Macedonia/Bulgaria) This is a Macedonian/Bulgarian dance taught by Ventsi Sotirov to this beautiful recording by Rayna. Samodivas (Bulgarian: Самодиви) are woodland fairies or nymphs found in South and West-Slavic folklore and mythology. Pronunciation: Sah-moh-DEE-vah Music: 7/8 meter (3+2+2) or LONG-short-short ( 1,2,3) Formation: Open circle; hands in W-position. Steps & Styling: Large movements Meas 7/8 meter Pattern 8 meas INTRODUCTION. No action. (Begin on vocal using left foot.) I. TO THE RIGHT, TO THE LEFT 1 Facing diag R and moving to the R: Large step on L in front of R (1), turning to face ctr and bringing R knee up in front of body, bounce on L (2), bounce again (3). 2 Step on R to R (1), step on L behind R (2), hold (3). 3 Step on R to R (1), step on L behind R (2), step on R to R (3). 4-12 Keep repeating this 3 measure phrase 3 more times, but lift R ft to R (instead of stepping on it) on the very last beat of meas 12. (cheat!) 13-24 Repeat meas 1-3 with opp dir and ftwk 4 times (NB! No “cheat step” needed!) II. LESNOTO AND “BLOO-BLOOPS” 1 Facing diag R and moving R: Step on R (1), lift R heel from floor while L ft makes a “bicycle movement” (2), step on L (3). 2 Repeat meas 1. 3 Turning to ctr, lift R knee on “&” in preparation for pumping R ft down in front while bouncing on L (1), bounce on L again while “sweeping” R ft slightly to R (2), step on R (3). -

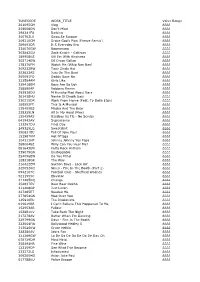

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

CAC 1 Grupa 01 FCI 15 Chien De Berger Belge

Nr.start Numele cainelui / Name COR Data nast./D.o.b. CAC 1 Grupa 01 F.C.I. 15 Chien de berger belge - Malinois Intermediara / Intermediate Masculi/Dogs 9 NERA in asteptare 29/02/2016 Ares && Mara Cr/B: Pop Ion Pr/O: Boiesan Veturia RO Deschisa / Open Femele/Bitches 10 TEA VON GROF BOX A 1968-15\/015 22/05/2015 Visszhang Csapas && Lorette Fly Dogs Attak Cr/B: Morariu Pr/O: Fagaras Claudiu-Dorin RO F.C.I. 15 Chien de berger belge - Tervueren Campioni / Champion Femele/Bitches 11 BLACK CARAMBAS AQUA FI50644\/13 20/09/2013 Heracles Of The Home Port && Ce Demetra Av Nangijala Cr/B: Sonja Enlund Pr/O: Siru Heinonen SF F.C.I. 83 Schipperke Intermediara / Intermediate Femele/Bitches 12 LEYU KURADZH RKF 4516583 06/04/2016 Ebony Sand's In The Black With Seasun AK && Deloran\u0163n\u0163Mardeck\u0163s White Cr/B: Akhtomova E Yu Pr/O: Akhtomova E Yu RU F.C.I. 332 Ceskoslovensky Vlcak Pui / Puppy Masculi/Dogs 13 O'TARIS MALY BYSTEREC LO1795122 16/12/2016 Gunner Maly Bysterec && Connie Vlci Tlapka Cr/B: Marek Medvecky Pr/O: Motta Stefania I Campioni / Champion Masculi/Dogs 14 CHARON SRDCERVAC COR A 264-15\/332 06/12/2014 CHEWBE && ANNE LEE SRDCERVAC Cr/B: DANIELA CILOVA Pr/O: FOCK RODICA RO 15 DEVIL MAVERICK LOI11\/33252 01/01/2011 Wakan Arimminum && Ch. Ombra Passo de Lupo Cr/B: Bonfiglioli Alessandra Pr/O: Degli Esposti Barbara I Juniori / Junior Femele/Bitches 16 WINDESPRESS MIRAGE LOI16178231 26/08/2016 Ch. Devil Maverick && Kyra Cr/B: Pacifici Mauro Pr/O: Degli Esposti Barbara I Campioni / Champion Femele/Bitches 17 FOLLIA DEI LUPI DI GUBBIO LO1416139 07/11/2013 Induk PDL && Chakra di Gubbio Cr/B: Masci Germano Pr/O: Stefania Motta I Munca / Working Femele/Bitches 18 ATHENA SHADOW OF THE PHOENIX RSR 14\/29729 25/12/2013 Zenith Od Uhoste && Nan\u00e0 di Villa Doria Cr/B: Alessia Pasquali Pr/O: Alessia Pasquali I F.C.I.