Architecturedsk 2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© 2008 Hyeong-Jong

© 2011 Elise Soyun Ahn SEEING TURKISH STATE FORMATION PROCESSES: MAPPING LANGUAGE AND EDUCATION CENSUS DATA BY ELISE SOYUN AHN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Policy Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2011 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Pradeep Dhillon, Chair Professor Douglas Kibbee Professor Fazal Rizvi Professor Thomas Schwandt Abstract Language provides an interesting lens to look at state-building processes because of its cross- cutting nature. For example, in addition to its symbolic value and appeal, a national language has other roles in the process, including: (a) becoming the primary medium of communication which permits the nation to function efficiently in its political and economic life, (b) promoting social cohesion, allowing the nation to develop a common culture, and (c) forming a primordial basis for self-determination. Moreover, because of its cross-cutting nature, language interventions are rarely isolated activities. Languages are adopted by speakers, taking root in and spreading between communities because they are legitimated by legislation, and then reproduced through institutions like the education and military systems. Pádraig Ó’ Riagáin (1997) makes a case for this observing that ―Language policy is formulated, implemented, and accomplishes its results within a complex interrelated set of economic, social, and political processes which include, inter alia, the operation of other non-language state policies‖ (p. 45). In the Turkish case, its foundational role in the formation of the Turkish nation-state but its linkages to human rights issues raises interesting issues about how socio-cultural practices become reproduced through institutional infrastructure formation. -

Compare Trabzon and Antalya in Terms of Tourism in My Opinion/To Me,

MIDDLE SCHOOL AND IMAM HATIP MIDDLE SCHOOL UPSWINGUPSWING ENGLISHENGLISH 88 STUDENT’S BOOK AUTHOR Baykal TIRAŞ Bu ki tap, Mil lî Eği tim Ba kan lığı, Ta lim ve Ter bi ye Ku ru lu Baş kan lığı’nın 28.05.2018 ta rih ve 78 sa yı lı (ekli listenin 156’ncı sırasında) ku rul ka ra rıy la 2018-2019 öğ re tim yı lın dan iti ba ren 5 (beş) yıl sü rey le ders ki ta bı ola- rak ka bul edil miş tir. TUTKU Y A Y I N C I L I K Her hak kı sak lı dır ve TUTKU KİTAP YAYIN BİLGİSAYAR DERS ARAÇ GEREÇLERİ TİCARET LİMİTET ŞİRKETİ’ne ait tir. İçin de ki şe kil, ya zı, me tin ve gra fik ler, ya yınevi nin iz ni ol ma dan alı na maz; fo to ko pi, tek sir, film şek lin de ve baş ka hiç bir şe kil de çoğal tı la maz, ba sı la maz ve ya yım la na maz. ISBN: 978-975-8851-91-1 Görsel Tasarım Uzmanı Aysel GÜNEY TÜRKEÇ TUTKU Y A Y I N C I L I K Kavacık Subayevleri Mah. Fahrettin Altay Cad. No.: 4/8 Keçiören/ANKARA tel.: (0.312) 318 51 51- 50 • belgegeçer: 318 52 51 İSTİKLÂL MARŞI Korkma, sönmez bu şafaklarda yüzen al sancak; Bastığın yerleri toprak diyerek geçme, tanı: Sönmeden yurdumun üstünde tüten en son ocak. Düşün altındaki binlerce kefensiz yatanı. O benim milletimin yıldızıdır, parlayacak; Sen şehit oğlusun, incitme, yazıktır, atanı: O benimdir, o benim milletimindir ancak. -

Faculty of Humanities

FACULTY OF HUMANITIES The Faculty of Humanities was founded in 1993 due to the restoration with the provision of law legal decision numbered 496. It is the first faculty of the country with the name of The Faculty of Humanities after 1982. The Faculty started its education with the departments of History, Sociology, Art History and Classical Archaeology. In the first two years it provided education to extern and intern students. In the academic year of 1998-1999, the Department of Art History and Archaeology were divided into two separate departments as Department of Art History and Department of Archaeology. Then, the Department of Turkish Language and Literature was founded in the academic year of 1999-2000 , the Department of Philosophy was founded in the academic year of 2007-2008 and the Department of Russian Language and Literature was founded in the academic year of 2010- 2011. English prep school is optional for all our departments. Our faculty had been established on 5962 m2 area and serving in a building which is supplied with new and technological equipments in Yunusemre Campus. In our departments many research enhancement projects and Archaeology and Art History excavations that students take place are carried on which are supported by TÜBİTAK, University Searching Fund and Ministry of Culture. Dean : Vice Dean : Prof. Dr. Feriştah ALANYALI Vice Dean : Assoc. Prof. Dr. Erkan İZNİK Secretary of Faculty : Murat TÜRKYILMAZ STAFF Professors: Feriştah ALANYALI, H. Sabri ALANYALI, Erol ALTINSAPAN, Muzaffer DOĞAN, İhsan GÜNEŞ, Bilhan -

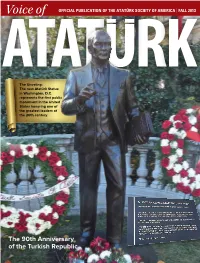

The 90Th Anniversary of the Turkish Republic CHAIRMAN’S COMMENTS the Atatürk Society of America Voice of 4731 Massachusetts Ave

Voice of OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE ATATÜRK SOCIETY OF AMERICA | FALL 2013 The Unveling: The new Atatürk Statue in Washington, D.C. represents the first public monument in the United States honoring one of the greatest leaders of the 20th century. The 90th Anniversary of the Turkish Republic CHAIRMAN’S COMMENTS The Atatürk Society of America Voice of 4731 Massachusetts Ave. NW CONTENTS Washington DC 20016 Phone 202 362 7173 Fax 202 363 4075 Mustafa Kemal’in Askerleriyiz... CHAIRMAN’S COMMENTS E-mail [email protected] 03 www.Ataturksociety.org Reversal of the Atatürk miracle— We are the soldiers of Mustafa Kemal... Destruction of Secular Democracy EXECUTIVE BOARD “There are two Mustafa Kemals. One, the flesh-and-blood Mustafa Kemal who now stands before Hudai Yavalar you and who will pass away. The other is you, all of you here who will go to the far corners of our President land to spread the ideals which must be defended with your lives if necessary. I stand for the nation's Prof. Bülent Atalay PRESIDENT’S COMMENTS dreams, and my life's work is to make them come true.” 04 Vice President —Mustafa Kemal Atatürk 10th of November — A day to Mourn Filiz Odabas-Geldiay Dr. Bulent Atalay Treasurer Members Believing secularism , democracy, science and technology Mirat Yavalar Aynur Uluatam Sumer 06 he year 2013 marked the 90th anniversary of the founding of the Turkish Republic. And ASA NEWS Secretary Ilknur Boray Hudai Yavalar 05 it was also the year of the most significant uprising in the history of Turkey. The chant Lecture by Dr. -

THE GREAT WAR and the TRAGEDY of ANATOLIA ATATURK SUPREME COUNCIL for CULTURE, LANGUAGE and HISTORY PUBLICATIONS of TURKISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY Serial XVI - No

THE GREAT WAR AND THE TRAGEDY OF ANATOLIA ATATURK SUPREME COUNCIL FOR CULTURE, LANGUAGE AND HISTORY PUBLICATIONS OF TURKISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY Serial XVI - No. 88 THE GREAT WAR AND THE TRAGEDY OF ANATOLIA (TURKS AND ARMENIANS IN THE MAELSTROM OF MAJOR POWERS) SALAHi SONYEL TURKISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRINTING HOUSE - ANKARA 2000 CONTENTS Sonyel, Salahi Abbreviations....................................................................................................................... VII The great war and the tragedy of Anatolia (Turks and Note on the Turkish Alphabet and Names.................................................................. VIII Armenians in the maelstrom of major powers) / Salahi Son Preface.................................................................................................................................... IX yel.- Ankara: Turkish Historical Society, 2000. x, 221s.; 24cm.~( Atattirk Supreme Council for Culture, Introduction.............................................................................................................................1 Language and History Publications of Turkish Historical Chapter 1 - Genesis of the 'Eastern Q uestion'................................................................ 14 Society; Serial VII - No. 189) Turco- Russian war of 1877-78......................................................................... 14 Bibliyografya ve indeks var. The Congress of B erlin....................................................................................... 17 ISBN 975 - 16 -

Who's Who in Politics in Turkey

WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY Sarıdemir Mah. Ragıp Gümüşpala Cad. No: 10 34134 Eminönü/İstanbul Tel: (0212) 522 02 02 - Faks: (0212) 513 54 00 www.tarihvakfi.org.tr - [email protected] © Tarih Vakfı Yayınları, 2019 WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY PROJECT Project Coordinators İsmet Akça, Barış Alp Özden Editors İsmet Akça, Barış Alp Özden Authors Süreyya Algül, Aslı Aydemir, Gökhan Demir, Ali Yalçın Göymen, Erhan Keleşoğlu, Canan Özbey, Baran Alp Uncu Translation Bilge Güler Proofreading in English Mark David Wyers Book Design Aşkın Yücel Seçkin Cover Design Aşkın Yücel Seçkin Printing Yıkılmazlar Basın Yayın Prom. ve Kağıt San. Tic. Ltd. Şti. Evren Mahallesi, Gülbahar Cd. 62/C, 34212 Bağcılar/İstanbull Tel: (0212) 630 64 73 Registered Publisher: 12102 Registered Printer: 11965 First Edition: İstanbul, 2019 ISBN Who’s Who in Politics in Turkey Project has been carried out with the coordination by the History Foundation and the contribution of Heinrich Böll Foundation Turkey Representation. WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY —EDITORS İSMET AKÇA - BARIŞ ALP ÖZDEN AUTHORS SÜREYYA ALGÜL - ASLI AYDEMİR - GÖKHAN DEMİR ALİ YALÇIN GÖYMEN - ERHAN KELEŞOĞLU CANAN ÖZBEY - BARAN ALP UNCU TARİH VAKFI YAYINLARI Table of Contents i Foreword 1 Abdi İpekçi 3 Abdülkadir Aksu 6 Abdullah Çatlı 8 Abdullah Gül 11 Abdullah Öcalan 14 Abdüllatif Şener 16 Adnan Menderes 19 Ahmet Altan 21 Ahmet Davutoğlu 24 Ahmet Necdet Sezer 26 Ahmet Şık 28 Ahmet Taner Kışlalı 30 Ahmet Türk 32 Akın Birdal 34 Alaattin Çakıcı 36 Ali Babacan 38 Alparslan Türkeş 41 Arzu Çerkezoğlu -

Biblical World

MAPS of the PAUL’SBIBLICAL MISSIONARY JOURNEYS WORLD MILAN VENICE ZAGREB ROMANIA BOSNA & BELGRADE BUCHAREST HERZEGOVINA CROATIA SAARAJEVO PISA SERBIA ANCONA ITALY Adriatic SeaMONTENEGRO PRISTINA Black Sea PODGORICA BULGARIA PESCARA KOSOVA SOFIA ROME SINOP SKOPJE Sinope EDIRNE Amastris Three Taverns FOGGIA MACEDONIA PONTUS SAMSUN Forum of Appius TIRANA Philippi ISTANBUL Amisos Neapolis TEKIRDAG AMASYA NAPLES Amphipolis Byzantium Hattusa Tyrrhenian Sea Thessalonica Amaseia ORDU Puteoli TARANTO Nicomedia SORRENTO Pella Apollonia Marmara Sea ALBANIA Nicaea Tavium BRINDISI Beroea Kyzikos SAPRI CANAKKALE BITHYNIA ANKARA Troy BURSA Troas MYSIA Dorylaion Gordion Larissa Aegean Sea Hadrianuthera Assos Pessinous T U R K E Y Adramytteum Cotiaeum GALATIA GREECE Mytilene Pergamon Aizanoi CATANZARO Thyatira CAPPADOCIA IZMIR ASIA PHRYGIA Prymnessus Delphi Chios Smyrna Philadelphia Mazaka Sardis PALERMO Ionian Sea Athens Antioch Pisidia MESSINA Nysa Hierapolis Rhegium Corinth Ephesus Apamea KONYA COMMOGENE Laodicea TRAPANI Olympia Mycenae Samos Tralles Iconium Aphrodisias Arsameia Epidaurus Sounion Colossae CATANIA Miletus Lystra Patmos CARIA SICILY Derbe ADANA GAZIANTEP Siracuse Sparta Halicarnassus ANTALYA Perge Tarsus Cnidus Cos LYCIA Attalia Side CILICIA Soli Korakesion Korykos Antioch Patara Mira Seleucia Rhodes Seleucia Malta Anemurion Pieria CRETE MALTA Knosos CYPRUS Salamis TUNISIA Fair Haven Paphos Kition Amathous SYRIA Kourion BEIRUT LEBANON PAUL’S MISSIONARY JOURNEYS DAMASCUS Prepared by Mediterranean Sea Sidon FIRST JOURNEY : Nazareth SECOND -

Ikili Rapor DEIK (Matbaa) Son.Pdf 1 10/4/11 6:25 PM

Ikili Rapor DEIK (Matbaa) Son.pdf 1 10/4/11 6:25 PM October 2011 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Ikili Rapor DEIK (Matbaa) Son.pdf 2 10/4/11 6:25 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Ikili Rapor DEIK (Matbaa) Son.pdf 3 10/4/11 6:25 PM October 2011 C M Y CM MY DEİK Foreign Economic Relations Board & BCG Boston Consulting Group CY All right reserved. CMY No part of this book may be used or reproduced, copied, distributed in any manner K without written permission of DEİK & BCG. Foreign Economic Relations Board (DEİK) TOBB Plaza, Harman Sokak No: 10 Kat: 5 Esentepe - Şişli 34394 İstanbul - Turkey Phone: +90 (212) 339 50 00 (pbx), +90 (212) 270 41 90 (pbx), Fax: +90 (212) 270 30 92 www.deik.org.tr - www.turkey-now.org www.dtik.org.tr - www.healthinturkey.com The Boston Consulting Group Kanyon Ofis, Büyükdere Cad. No: 185 K: 13 Levent 34394 İstanbul - Turkey Phone: +90 (212) 317 80 08 Fax: +90 (212) 317 82 10 www.bcg.com.tr ISBN NO: 978-605-5979-06-5 DEİK Yayınları: 771-2011/9-b1 Küresel Ekonomide Türkiye Serisi Turkey in Global Economy Series Ikili Rapor DEIK (Matbaa) Son.pdf 4 10/4/11 6:25 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Ikili Rapor DEIK (Matbaa) Son.pdf 5 10/4/11 6:25 PM DEİK President’s Message Dear Readers, Turkey has achieved remarkable economic and political development in the new millennium. A sound macroeco- nomic strategy combined with prudent scal policies and major structural reforms have, over a period of 10 years, facilitated Turkey’s successful integration into the global economic system. -

Poor Ottoman Turkish Women During World War I : Women’S Experiences and Politics in Everyday Life, 1914-1923 Ikbal Elif Mahir-Metinsoy

Poor Ottoman Turkish women during World War I : women’s experiences and politics in everyday life, 1914-1923 Ikbal Elif Mahir-Metinsoy To cite this version: Ikbal Elif Mahir-Metinsoy. Poor Ottoman Turkish women during World War I : women’s experiences and politics in everyday life, 1914-1923. History. Université de Strasbourg, 2012. English. NNT : 2012STRAG004. tel-01885891 HAL Id: tel-01885891 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01885891 Submitted on 2 Oct 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITÉ DE STRASBOURG ÉCOLE DOCTORALE SCIENCES HUMAINES ET SOCIALES / PERSPECTIVES EUROPÉENS Cultures et Sociétés en Europe THÈSE présentée par : Ikbal Elif MAHIR METINSOY soutenue le : 29 juin 2012 pour obtenir le grade de : Docteur de l’Université de Strasbourg Discipline/ Spécialité : Histoire contemporaine Les femmes défavorisées ottomanes turques pendant la Première Guerre mondiale Les expériences des femmes et la politique féminine dans la vie quotidienne, 1914-1923 [Poor Ottoman Turkish Women during World War I : Women’s Experiences and Politics in Everyday Life, 1914-1923] THÈSE dirigée par : M. DUMONT Paul Professeur des universités, Université de Strasbourg Mme. KOKSAL Duygu Professeur associé HDR, Université de Boğaziçi RAPPORTEURS : M. -

The Persistence of the Turkish Nation in the Mausoleum of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk Christopher S.Wilson

6 The persistence of the Turkish nation in the mausoleum of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk Christopher S.Wilson Introduction The Republic of Turkey, founded in 1923 after a war of independence, created a history for its people that completely and consciously bypassed its Ottoman predecessor. An ethnie called “the Turks,” existent in the multicultural Ottoman Empire only as a general name used by Europeans, was imagined and given a story linking it with the nomads of Central Asia, the former Hittite and Phrygian civilizations of Anatolia, and even indirectly with the ancient Sumerian and Assyrian civilizations of Mesopotamia. In the early years of the Turkish Republic, linguistic, anthropological, archaeological and historical studies were all conducted in order to formulate and sustain such claims. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the revolutionary responsible for the Turkish Republic, was the driving force behind this state-sponsored construction of “the Turks”—even his surname is a fabrication that roughly translates as “Ancestor/Father of the Turks.” It is no surprise then that the structure built to house the body of Atatürk after his death, his mausoleum called Anitkabir, also works to perpetuate such storytelling. Anitkabir, however, is more than just the final resting place of Atatürk’s body—it is a public monument and stage-set for the nation, and a representation of the hopes and ideals of the Republic of Turkey. Sculptures, reliefs, floor paving and even ceiling patterns are combined in a narrative spatial experience that illustrates, explains and reinforces the imagined history of the Turks, their struggle for independence, and the founding of the Republic of Turkey after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. -

The Politics of Abandoned Property and the Population Exchange in Turkey, 1921-1945

Bamberger 9 Orientstudien The Dowry of the State? The Politics of Abandoned Property and the Population Exchange in Turkey, 1921-1945 Ellinor Morack Izmir and the population exchange: The politics of abandoned property and refugee compensation, 1922 - 1930 Zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades eingereicht am Fachbereich Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin im Jahr 2013 vorgelegt von Sara Ellinor Morack 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Ulrike Freitag 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Christoph Herzog Tag der Disputation: 1. November 2013 9 Bamberger Orientstudien Bamberger Orientstudien hg. von Lale Behzadi, Patrick Franke, Geoffrey Haig, Christoph Herzog, Birgitt Hoffmann, Lorenz ornK und Susanne Talabardon Band 9 2017 The Dowry of the State? The Politics of Abandoned Property and the Population Exchange in Turkey, 1921-1945 Ellinor Morack 2017 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Informationen sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de/ abrufbar. Diese Arbeit hat der Fakultät Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin als Dissertation vorgelegen. 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Ulrike Freitag 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Christoph Herzog Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 01.11.2013 Dieses Werk ist als freie Onlineversion über den Hochschulschriften-Server (OPUS; http://www.opus-bayern.de/uni-bamberg/) der Universitätsbiblio- thek Bamberg erreichbar. Kopien und Ausdrucke -

Nevşehir Haci Bektaş Veli Üniversitesi Fen – Edebiyat Fakültesi

NEVŞEHİR HACI BEKTAŞ VELİ ÜNİVERSİTESİ FEN – EDEBİYAT FAKÜLTESİ İ İ İ Ö İ i 24. INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON MEDIEVAL and TURKISH PERIOD ARCHAEOLOGY AND ART HISTORY STUDIES 24. ULUSLARARASI ORTAÇAĞ ve TÜRK DÖNEMİ KAZILARI ve SANAT TARİHİ ARAŞTIRMALARI SEMPOZYUMU Basıldığı Yer: Basım Tarihi: 2020 Tel: Fax: https://uotk.nevsehir.edu.tr/ ISBN: ii 24. ULUSLARARASI ORTAÇAĞ ve TÜRK DÖNEMİ KAZILARI ve SANAT TARİHİ ARAŞTIRMALARI SEMPOZYUMU 7-9 Ekim 2020 Sempozyum Ana Başlıkları Sanat Tarihi Ortaçağ ve Sonrası Kazı Araştırmaları Kültürel Miras ve Koruma Arkeolojik Alan Yönetimi Arkeometri Restorasyon ve Müzecilik Metodoloji ve Terminoloji Düzenleme Kurulu Prof. Dr. Semih AKTEKİN (NEVÜ. Rektörü) Doç. Dr. Ayşe BUDAK Doç. Dr. Tolga B. UYAR Dr. Öğr. Üy. Alper ALTIN Dr. Öğr. Üy. Savaş MARAŞLI Arş. Gör. Dr. Can ERPEK Öğr. Gör. Dr. Ahmet ARI Arş. Gör. Enes KAVALÇALAN Bilim Kurulu: Onur Kurulu: Ahmet ÇAYCI Gülgün Osman Ayşıl TÜKEL Rüçhan ARIK KÖROĞLU ERAVŞAR YAVUZ Ahmet Ali Haldun ÖZKAN Remzi DURAN Ebru PARMAN Selçuk BAYHAN MÜLAYİM Ali BAŞ Halit ÇAL Rüstem BOZER Filiz Yaşar ÇORUHLU YENİŞEHİRLİOĞLU Ali Osman Hüseyin Sacit PEKAK Gönül CANTAY UYSAL YURTTAŞ Asnu BİLBAN İnci KUYULU Scott REDFORD Gönül ÖNEY YALÇIN ERSOY Ayşe AYDIN İsmail AYTAÇ Sedat Rahmi Hüseyin BAYRAKAL ÜNAL Ayşe ÇAYLAK Kadir PEKTAŞ Sema DOĞAN Hakkı ÖNKAL TÜRKER Bozkurt ERSOY Kenan BİLİCİ Yıldıray ÖZBEK M. Baha TANMAN Candan ÜLKÜ Mehmet Zeliha DEMİREL Mustafa Servet ÖZKARCI GÖKALP AKPOLAT Engin AKYÜREK Nermin ŞAMAN Zeynep Oluş ARIK DOĞAN MERCANGÖZ Fahriye Nilay ÇORAĞAN Sacit PEKAK Ömür BAKIRER BAYRAM iii İÇİNDEKİLER SU ALTINDA KALAN HISN-I KEYFA AŞAĞI ŞEHİRİN’İN ARDINDAN .................. 3 After The Aşağı Şehir Of Hısn-ı Keyfa Left Underwater ...................................................