Pakistan Country Handbook This Handbook Provides Basic Reference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section Iv District Profiles Awaran

SECTION IV DISTRICT PROFILES AWARAN Awaran district lies in the south of the Balochistan province. Awaran is known as oasis of AGRICULTURAL INFORMATION dates. The climate is that of a desert with hot summer and mild winter. Major crops include Total cultivated area (hectares) 23,600 wheat, barley, cotton, pulses, vegetable, fodder and fruit crops. There are three tehsils in the district: Awaran, Jhal Jhao and Mashkai. The district headquarter is located at Awaran. Total non-cultivated area (hectares) 187,700 Total area under irrigation (hectares) 22,725 Major rabi crop(s) Wheat, vegetable crops SOIL ATTRIBUTES Mostly barren rocks with shallow unstable soils Major kharif crop(s) Cotton, sorghum Soil type/parent material material followed by nearly level to sloppy, moderately deep, strongly calcareous, medium Total livestock population 612,006 textured soils overlying gravels Source: Crop Reporting Services, Balochistan; Agriculture Census 2010; Livestock Census 2006 Dominant soil series Gacheri, Khamara, Winder *pH Data not available *Electrical conductivity (dS m-1) Data not available Organic matter (%) Data not available Available phosphorus (ppm) Data not available Extractable potassium (ppm) Data not available Farmers availing soil testing facility (%) 2 (Based on crop production zone wise data) Farmers availing water testing facility (%) 0 (Based on crop production zone wise data) Source: District Soil Survey Reports, Soil Survey of Pakistan Farm Advisory Centers, Fauji Fertilizer Company Limited (FFC) Inputs Use Assessment, FAO (2018) Land Cover Atlas of Balochistan (FAO, SUPARCO and Government of Balochistan) Source: Information Management Unit, FAO Pakistan *Soil pH and electrical conductivity were measured in 1:2.5, soil:water extract. -

Future Technology and International Cooperation a UK Perspective

MAY Future Technology and International Cooperation A UK perspective In 2011, NATO’s Integrated Air Defence (NATINAD) and the supporting NATO Integrated Air Defence System (NATINADS) marked 50 years of safeguarding NATO’s skies. In order to successfully reach future milestones NATO must continue (and in many cases improve) its air defence interoperability across the strategic, operational and tactical domains. In order for this to become reality a combination of exploiting synergies and acknowledging that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts1 is required at all levels. Recent improvements and a greater focus on future capability within the UK’s Joint Ground Based Air Defence (Jt GBAD) will enable the Formation to deploy its units and sub-units in order to operate the latest air defence weapon systems, within a multinational environment, against a near-peer adversary or asymmetric threat, and win. Major Charles W.I. May RA – 14 (Cole’s Kop) Battery Royal Artillery* the strategic direction of the British Armed ‘If I didn‘t have air supremacy, I wouldn‘t be here.’ Forces, and subsequently the operational level (SACEUR, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, June 1944) construct. As the new direction is towards Joint Force 2025 (JF2025) it is pragmatic for this paper to focus on the next 10 years. The his article will highlight the UK military’s purpose is to identify and highlight the Tstrategic situation, perception and under- pertinent capability enhancements and future standing of the air threat before explaining the vision of the UK’s Ground Based Air Defence new military structure to which the Formation Formation and its developing role within the is adapting. -

Mt-2018-2-3.Pdf

2–3/2018 Kr 48,- TIDSAM 1098-02 NORWEGIAN DEFENCE And ECURITY ndUSTRIES ssOCIATION 9 770806 615906 02 S I A RETURUKEReturuke 39 v 12 STYRETS ÅRSBERETNING 2017 GiraffeFlexible protection for mobile forces1X Saab Technologies Norway AS saab.no CONTENTS CONTENTS: MINE CLEARANCE Editor-in-Chief: 2 The future is unmanned M.Sc. Bjørn Domaas Josefsen NSM 6 US Navy selects Naval Strike Missile NORDIC DEFENCE CO- OPERATION; NOT NECESSARILY DOOMED TO FAILURE NORDEFCO 8 NDIS (Nordic Defence Industry Seminar) 2018 Nordic collaboration within the defence sector has for many years been riddled with good intentions, but often with meagre results to show for all the efforts. FSi The Nordic countries are often regarded as a common unit, with 11 Norwegian Defence and Security almost similar languages (except Finland), a great deal of cultural Industries Association (FSi) similarity, and a long-standing tradition for co-operation on a number of different arenas. And yet, there are significant differences between the countries, not 17 ÅRSRAPPORT 2017 least from a security political and military point of view. Two of the Nordic countries are members of NATO, while two are BULLETIN BOARD FOR DEFENCE, alliance-free. Finland has an extended land border to Russia, while INDUSTRY AND TRADE Norway has a short land border as well as a long demarcation line at sea. Neither Sweden nor Denmark have land borders to Russia. 59 Gripen Plant in Brazil Sweden and Finland have huge forest regions, where Norway has 61 Command post shelters for Kongsberg fjords, mountains and deep valleys; Denmark mainly consists of a flat 63 Training Systems for the Swedish Army culture landscape spread across some mainland and a few large islands. -

Adopting Cloud Computing in the Pakistan Navy

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive DSpace Repository Theses and Dissertations 1. Thesis and Dissertation Collection, all items 2015-06 Adopting cloud computing in the Pakistan Navy Asim, Tahir Majeed Monterey, California: Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/45807 Downloaded from NPS Archive: Calhoun NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS ADOPTING CLOUD COMPUTING IN THE PAKISTAN NAVY by Tahir Majeed Asim June 2015 Thesis Advisor: Dan Boger Co-Advisor: Dorothy E. Denning Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2015 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS ADOPTING CLOUD COMPUTING INTHE PAKISTAN NAVY 6. AUTHOR(S) Tahir Majeed Asim 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 9. SPONSORING /MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders (W/Out Cnic) As of December 31, 2017

ASKARI BANK LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS (W/OUT CNIC) AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2017 S. NO. FOLIO NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDERS ADDRESSES OF THE SHAREHOLDERS NO. OF SHARES 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN C/O BANK OF AMERICA, BLUE AREA, ISLAMABAD. 2878 12 68 MR. WASEEM AHMED HOUSE NO.485, STREET NO.17, CHAKLALA SCHEME-III, RAWALPINDI. 5945 13 71 MS. SHAMEEM QUAVI SIDDIQUI 112/1, 13TH STREET, PHASE-VI, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, KARACHI-75500. 2695 14 74 MS. YAZDANI BEGUM HOUSE NO.A-75, BLOCK-13, GULSHAN-E-IQBAL, KARACHI. -

Faunistics of Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Rephalocera) with Some New Records from Quetta, Balochistan, Pakistan

Vol. 3, Issue 1, Pp: (26-35), March, 2019 FAUNISTICS OF BUTTERFLIES (LEPIDOPTERA: REPHALOCERA) WITH SOME NEW RECORDS FROM QUETTA, BALOCHISTAN, PAKISTAN Fariha Mengal1, Imtiaz Ali Khan2, Muhammad Ather Rafi2, Saima Durrani1, Muhammad Qasim3, Gul Makai1, Muhammad Kamal Sheik4, Ghulam Rasul4, Naveed Iftikhar Jajja3 1Department of Zoology, Sardar Bahadur Khan Women University, Quetta. 2 University of Swabi, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. 3Department of Entomology, Faculty of Agriculture, University of the Poonch, Rawalakot, Azad Jammu and KashmiR. 4Planning and Development Division, Pakistan Agricultural Research Council, Islamabad. ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Article History: th This study was conducted to explore the butterfly fauna of Quetta, Balochistan. Received: 10 Jan 2019 A totaling 286 specimens of butterflies have been collected from different Accepted: : 30th June 2019 Published online: 18th Oct 2019 localities of Quetta. Out of 286 collected specimens 27 species from 22 genera Author’s contribution under 4 families Lycaenidae, Nymphalidae Papilionidae and Pieridae have been All authors have contributed equally in identified. Out of 27 identified species, 11 species represented family this study. Lycaenidae, eight (08) species represented family Nymphalidae, seven (07) Key words: species identified under family Pieridae and one (01) species identified under Balochistan, Butterfly Fauna, family Papilionidae. One species, Pseudochazara mamurra recorded first time Lepidoptera, Pakistan, Quetta. from Pakistan. Three (03) species, namely Zizeeria maha, Zizula hylax and Zizina otis are reported first time from Balochistan while five (05) species i.e. Lampides boeticus, Polyommatus bogra, Polyommatus florenciae, Eumenis thelephassa and Eurema hecabe are first time from Quetta. 1. INTRODUCTION The butterfly fauna of Pakistan have been well studies by many authors. -

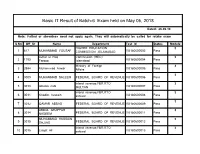

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam Held on May 05, 2018

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam S.No Off_Sr Name Department Test Id Status Module HIGHER EDUCATION 3 1 617 MUHAMMAD YOUSAF COMMISSION ,ISLAMABAD VU180600002 Pass Azhar ul Haq Commission (HEC) 3 2 1795 Farooq Islamabad VU180600004 Pass Ministry of Foreign 3 3 2994 Muhammad Anwar Affairs VU180600005 Pass 3 4 3009 MUHAMMAD SALEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600006 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 5 3010 Ghulan nabi MULTAN VU180600007 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 6 3011 Khadim hussain sahiwal VU180600008 Pass 3 7 3012 QAMAR ABBAS FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600009 Pass ABDUL GHAFFAR 3 8 3014 NADEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600011 Pass MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN 3 9 3015 SAJJAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600012 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 10 3016 Liaqat Ali sahiwal VU180600013 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 11 3017 Tariq javed sahiwal VU180600014 Pass 3 12 3018 AFTAB AHMAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600015 Pass Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Muhammad inam-ul- inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 13 3019 haq MULTAN VU180600016 Pass Ministry of Defense (Defense Division) 3 Rawalpindi. 14 4411 Asif Mehmood VU180600018 Pass 3 15 4631 Rooh ul Amin Pakistan Air Force VU180600022 Pass Finance/Income Tax 3 16 4634 Hammad Qureshi Department VU180600025 Pass Federal Board Of Revenue 3 17 4635 Arshad Ali Regional Tax-II VU180600026 Pass 3 18 4637 Muhammad Usman Federal Board Of Revenue VU180600027 -

*‡Table 5. Ethnic and National Groups

T5 Table[5.[Ethnic[and[National[Groups T5 T5 TableT5[5. [DeweyEthnici[Decimaand[NationalliClassification[Groups T5 *‡Table 5. Ethnic and National Groups The following numbers are never used alone, but may be used as required (either directly when so noted or through the interposition of notation 089 from Table 1) with any number from the schedules, e.g., civil and political rights (323.11) of Navajo Indians (—9726 in this table): 323.119726; ceramic arts (738) of Jews (—924 in this table): 738.089924. They may also be used when so noted with numbers from other tables, e.g., notation 174 from Table 2 In this table racial groups are mentioned in connection with a few broad ethnic groupings, e.g., a note to class Blacks of African origin at —96 Africans and people of African descent. Concepts of race vary. A work that emphasizes race should be classed with the ethnic group that most closely matches the concept of race described in the work Except where instructed otherwise, and unless it is redundant, add 0 to the number from this table and to the result add notation 1 or 3–9 from Table 2 for area in which a group is or was located, e.g., Germans in Brazil —31081, but Germans in Germany —31; Jews in Germany or Jews from Germany —924043. If notation from Table 2 is not added, use 00 for standard subdivisions; see below for complete instructions on using standard subdivisions Notation from Table 2 may be added if the number in Table 5 is limited to speakers of only one language even if the group discussed does not approximate the whole of the -

A Review on Silver Nanoparticles: Classification, Various Methods Of

water Review A Review on Silver Nanoparticles: Classification, Various Methods of Synthesis, and Their Potential Roles in Biomedical Applications and Water Treatment Muhammad Zahoor 1,* , Nausheen Nazir 1 , Muhammad Iftikhar 1, Sumaira Naz 1, Ivar Zekker 2,*, Juris Burlakovs 3 , Faheem Uddin 4, Abdul Waheed Kamran 5, Anna Kallistova 6, Nikolai Pimenov 6 and Farhat Ali Khan 7 1 Department of Biochemistry, University of Malakand, Chakdara 18800, Pakistan; [email protected] (N.N.); [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (S.N.) 2 Faculty of Science, Institute of Chemistry, University of Tartu, 51014 Tartu, Estonia 3 Institute of Forestry and Rural Engineering, Estonian University of Life Sciences, 51006 Tartu, Estonia; [email protected] 4 Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Engineering & Technology, Mardan 23200, Pakistan; [email protected] 5 Department of Chemistry, University of Malakand, Chakdara 18800, Pakistan; [email protected] 6 Research Centre of Biotechnology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Winogradsky Institute of Microbiology, 119071 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (N.P.) 7 Department of Pharmacy, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University, Sheringal 18050, Pakistan; [email protected] Citation: Zahoor, M.; Nazir, N.; * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (I.Z.) Iftikhar, M.; Naz, S.; Zekker, I.; Burlakovs, J.; Uddin, F.; Kamran, A.W.; Kallistova, A.; Pimenov, N.; Abstract: Recent developments in nanoscience have appreciably modified how diseases are pre- et al. A Review on Silver vented, diagnosed, and treated. Metal nanoparticles, specifically silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), are Nanoparticles: Classification, Various widely used in bioscience. From time to time, various synthetic methods for the synthesis of AgNPs Methods of Synthesis, and Their are reported, i.e., physical, chemical, and photochemical ones. -

Group Identity and Civil-Military Relations in India and Pakistan By

Group identity and civil-military relations in India and Pakistan by Brent Scott Williams B.S., United States Military Academy, 2003 M.A., Kansas State University, 2010 M.M.A., Command and General Staff College, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Security Studies College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Abstract This dissertation asks why a military gives up power or never takes power when conditions favor a coup d’état in the cases of Pakistan and India. In most cases, civil-military relations literature focuses on civilian control in a democracy or the breakdown of that control. The focus of this research is the opposite: either the returning of civilian control or maintaining civilian control. Moreover, the approach taken in this dissertation is different because it assumes group identity, and the military’s inherent connection to society, determines the civil-military relationship. This dissertation provides a qualitative examination of two states, Pakistan and India, which have significant similarities, and attempts to discern if a group theory of civil-military relations helps to explain the actions of the militaries in both states. Both Pakistan and India inherited their military from the former British Raj. The British divided the British-Indian military into two militaries when Pakistan and India gained Independence. These events provide a solid foundation for a comparative study because both Pakistan’s and India’s militaries came from the same source. Second, the domestic events faced by both states are similar and range from famines to significant defeats in wars, ongoing insurgencies, and various other events. -

Census of India, 1931

·. ---~ . Census of India, 1931 VOL. I-INDIA Part 1--Report • by J. H. HUTTON, C.J.E., D.Sc., F.A.S.B., Carreapoacllaa Me1nber of the Anthropologieche Gesell-chait of Vlama To which ia annexed an ACTUARIAL REPORT by L S. Vaidyanathan, F. I. A. DELHI: MANAGRR OF' PUBLICATION8 1933 Governmen~ of In~~ ~blications are _obtainable from the Manager of Publica tions, Ctvil Lmes, Old Delhi, a.nd from the following Agents :- EUROPE. U-45.2.St') OJ' OniCE THE HIGH COMMISSIONER F0R INDIA, G1 lNDIA HousE, ALDwYCH, LONDON, W. C. 2. v l• I And at all Booksellers. INDIA AND CEYLON : Provincial Book Depots. 16$l6 2.. ..IAJ,f:Ml :..:._Superintet•dent, Government Press, Mount Road, Madras liOltlHY :--:-.Superir.tendent, Go;-crnment Print ,ng and Stationery, Queen's Road, Bombay. StNL> :- -Ltbrary attad1ed to the Oflice of the Commissioner in Sind, Karachi. H!!:I>'i.\L :-Bengal :-iecretariat Book Deput. Writers' Buildings, Room No. 1, Ground Floor, Calcutta. UNJTEJJ PrrovJ:;CEs OF MRA AND OuDH :-.Superintendent of Government Press, United Provinces of ARra and Oudh, Allahabad. PUNJAB :-Superintendent, Govemment Printing, Punjab, Lahore. BURMA :-Superintendent, Government Printing, Burma, Rangoon. CENTRAL PROVINCES ANL> BERAR :-Superintendent, Government Printing, Central Provinces Nagpur. '.\.ssAM :-Superintendent, Assam Secretariat Press, Shillong. ' BJHAn AND ORISSA :-Superintendent, Government Printing, Bihar altd Orissa, P. 0. Gu!,.u·bagh Patna. NoRTH-\\TE.ST FRONTIER PROVJNC£ :-Manager, Goverument Printing and Stationery, Pe:;haw~. Thacker Spink & Co., Ltd., Calcutta and Simla. The :::\tudents Own Rook Depot, Dharwar. W. Newman & Co., Ltd., Calcutta. Shri Shankar Karnataka Pustal-"a Bhandara, Mala- 8. K. -

Police Organisations in Pakistan

HRCP/CHRI 2010 POLICE ORGANISATIONS IN PAKISTAN Human Rights Commission CHRI of Pakistan Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative working for the practical realisation of human rights in the countries of the Commonwealth Human Rights Commission of Pakistan The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) is an independent, non-governmental organisation registered under the law. It is non-political and non-profit-making. Its main office is in Lahore. It started functioning in 1987. The highest organ of HRCP is the general body comprising all members. The general body meets at least once every year. Executive authority of this organisation vests in the Council elected every three years. The Council elects the organisation's office-bearers - Chairperson, a Co-Chairperson, not more than five Vice-Chairpersons, and a Treasurer. No office holder in government or a political party (at national or provincial level) can be an office bearer of HRCP. The Council meets at least twice every year. Besides monitoring human rights violations and seeking redress through public campaigns, lobbying and intervention in courts, HRCP organises seminars, workshops and fact-finding missions. It also issues monthly Jehd-i-Haq in Urdu and an annual report on the state of human rights in the country, both in English and Urdu. The HRCP Secretariat is headed by its Secretary General I. A. Rehman. The main office of the Secretariat is in Lahore and branch offices are in Karachi, Peshawar and Quetta. A Special Task Force is located in Hyderabad (Sindh) and another in Multan (Punjab), HRCP also runs a Centre for Democratic Development in Islamabad and is supported by correspondents and activists across the country.