The United States Army—Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States Atomic Army, 1956-1960 Dissertation

INTIMIDATING THE WORLD: THE UNITED STATES ATOMIC ARMY, 1956-1960 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paul C. Jussel, B.A., M.M.A.S., M.S.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Advisor Professor John R. Guilmartin __________________ Professor William R. Childs Advisor Department of History ABSTRACT The atomic bomb created a new military dynamic for the world in 1945. The bomb, if used properly, could replace the artillery fires and air-delivered bombs used to defeat the concentrated force of an enemy. The weapon provided the U.S. with an unparalleled advantage over the rest of the world, until the Soviet Union developed its own bomb by 1949 and symmetry in warfare returned. Soon, theories of warfare changed to reflect the belief that the best way to avoid the effects of the bomb was through dispersion of forces. Eventually, the American Army reorganized its divisions from the traditional three-unit organization to a new five-unit organization, dubbed pentomic by its Chief of Staff, General Maxwell D. Taylor. While atomic weapons certainly had an effect on Taylor’s reasoning to adopt the pentomic organization, the idea was not new in 1956; the Army hierarchy had been wrestling with restructuring since the end of World War II. Though the Korean War derailed the Army’s plans for the early fifties, it returned to the forefront under the Eisenhower Administration. The driving force behind reorganization in 1952 was not ii only the reoriented and reduced defense budget, but also the Army’s inroads to the atomic club, formerly the domain of only the Air Force and the Navy. -

January and February

VIETNAM VETERANS OF AMERICA Office of the National Chaplain FOUAD KHALIL AIDE -- Funeral service for Major Fouad Khalil Aide, United States Army (Retired), 78, will be Friday, November 13, 2009, at 7 p.m. at the K.L. Brown Funeral Home and Cremation Center Chapel with Larry Amerson, Ken Rollins, and Lt. Col. Don Hull officiating, with full military honors. The family will receive friends Friday evening from 6-7 p.m. at the funeral home. Major Aide died Friday, November 6, 2009, in Jacksonville Alabama. The cause of death was a heart attack. He is survived by his wife, Kathryn Aide, of Jacksonville; two daughters, Barbara Sifuentes, of Carrollton, Texas, and Linda D'Anzi, of Brighton, England; two sons, Lewis Aide, of Columbia, Maryland, and Daniel Aide, of Springfield, Virginia, and six grandchildren. Pallbearers will be military. Honorary pallbearers will be Ken Rollins, Matt Pepe, Lt. Col. Don Hull, Jim Hibbitts, Jim Allen, Dan Aide, Lewis Aide, VVA Chapter 502, and The Fraternal Order of Police Lodge. Fouad was commissioned from the University of Texas ROTC Program in 1953. He served as a Military Police Officer for his 20 years in the Army. He served three tours of duty in Vietnam, with one year as an Infantry Officer. He was recalled to active duty for service in Desert Shield/Desert Storm. He was attached to the FBI on their Terrorism Task Force because of his expertise in the various Arabic dialects and cultures. He was fluent in Arabic, Spanish and Vietnamese and had a good working knowledge of Italian, Portuguese and French. -

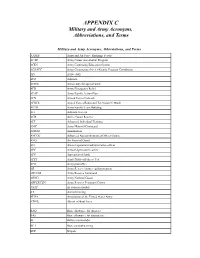

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

Wead Ethics Instructor; Thm, DMIN Command and General Staff College Ft

The Evolution of Military Ethics in the United States Army Ethics and morale leadership are topics with which all Soldiers and especially officers should be familiar. After all, ADP 6-22, Army Leadership, specifies that officer will use ethical reasoning in decision making and commanders will establish an ethical climate in their organization. Nevertheless, officers must also understand that they are not alone in maintaining the ethical standards and climates of the military. A number of organizations and branches support ethics in the military, and it is beneficial for Soldiers to be aware of those organizations and what they do. This article will assist in that endeavor." From 1775 to about 1970 ethics education in the United States Army took the form of moral leadership or moral conduct training for enlisted Soldiers and cadets. These moral leadership classes consisted of instruction in the principles of the Judeo-Christian faiths, values, citizenship, 1 and leadership. 2 The subject of the training reflected American values of the time. Much of this education was mandated by commanders. For example, the United States Military Academy had compulsory attendance at chapel until 19733. Officers, being gentlemen, were understood to be morally formed as a result of both their upbringing and education and therefore excused from moral leadership training.4 Two events happened at the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s to change this paradigm. The first was the My Lai massacre and subsequent trial in which 30 officers were implicated in the massacre and subsequent cover up of the atrocities in the Vietnamese village. -

(ADP) 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession

ADP 6-22 ARMY LEADERSHIP AND THE PROFESSION JULY 2019 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. This publication supersedes ADP 6-22 and ADRP 6-22, dated 1 August 2012 and ADRP 1, dated 14 June 2015. HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https://armypubs.army.mil/) and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard). *ADP 6-22 Army Doctrine Publication Headquarters No. 6-22 Department of the Army Washington, DC, 31 July 2019 ARMY LEADERSHIP AND THE PROFESSION Contents Page PREFACE.................................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... v Chapter 1 THE ARMY ................................................................................................................ 1-1 A Shared Legacy ....................................................................................................... 1-1 The Army Profession ................................................................................................. 1-2 Army Leadership ....................................................................................................... 1-3 Army Leadership Requirements Model ..................................................................... 1-6 Dynamics of Leadership ........................................................................................... -

Military Service Records at the National Archives Military Service Records at the National Archives

R E F E R E N C E I N F O R M A T I O N P A P E R 1 0 9 Military Service Records at the national archives Military Service Records at the National Archives REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 1 0 9 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC Compiled by Trevor K. Plante Revised 2009 Plante, Trevor K. Military service records at the National Archives, Washington, DC / compiled by Trevor K. Plante.— Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, revised 2009. p. ; cm.— (Reference information paper ; 109) 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration —Catalogs. 2. United States — Armed Forces — History — Sources. 3. United States — History, Military — Sources. I. United States. National Archives and Records Administration. II. Title. Front cover images: Bottom: Members of Company G, 30th U.S. Volunteer Infantry, at Fort Sheridan, Illinois, August 1899. The regiment arrived in Manila at the end of October to take part in the Philippine Insurrection. (111SC98361) Background: Fitzhugh Lee’s oath of allegiance for amnesty and pardon following the Civil War. Lee was Robert E. Lee’s nephew and went on to serve in the Spanish American War as a major general of the United States Volunteers. (RG 94) Top left: Group of soldiers from the 71st New York Infantry Regiment in camp in 1861. (111B90) Top middle: Compiled military service record envelope for John A. McIlhenny who served with the Rough Riders during the SpanishAmerican War. He was the son of Edmund McIlhenny, inventor of Tabasco sauce. -

Military Health Care in Transition

from AUSA 's Institute of Land Warfare MILITARY HEALTH CARE IN TRANSITION The long-established ways of providing medical care can also be provided to family members. If care is not for soldiers, militaty retirees, and family members are available or the family member does not live near a mili changing. The bond with career soldiers for lifetime tmy clinic, a statement of nonavailability will be issued, medical care - though not an entitlement in law- is authorizing use of CHAMPUS. When on extended ac being redefined. The historic promise of free lifetime tive duty, reserve component soldiers and their families medical care is coming face to face with the fiscal reali will receive the same health care as active duty soldiers ties of the post-Cold War era. and families. During the Cold War, the Defense Department main In this resource-constrained environment, a militmy tained a large medical infrastructure of personnel and retiree and family members, not yet eligible for Medi- facilities. Providing health care, may recetve space care for service members available care in a military The bond with career soldiers for life-time (and for families and retir clinic or hospital. If care is medical care ... is being redefined. ees on a space-available unavailable at the militaty fa- basis) was a means to cility or the patient lives too maintain medical skills and readiness. It also fulfilled far away, the retiree or family member will have to ob the promise of continuing medical care to retirees. tain care through CHAMPUS. In the post-Cold War era, militaty medical resources When the militaty retiree or family member becomes are more constrained. -

The Korean War

N ATIO N AL A RCHIVES R ECORDS R ELATI N G TO The Korean War R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 1 0 3 COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 N AT I ONAL A R CH I VES R ECO R DS R ELAT I NG TO The Korean War COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 103 N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives records relating to the Korean War / compiled by Rebecca L. Collier.—Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2003. p. ; 23 cm.—(Reference information paper ; 103) 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration.—Catalogs. 2. Korean War, 1950-1953 — United States —Archival resources. I. Collier, Rebecca L. II. Title. COVER: ’‘Men of the 19th Infantry Regiment work their way over the snowy mountains about 10 miles north of Seoul, Korea, attempting to locate the enemy lines and positions, 01/03/1951.” (111-SC-355544) REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 103: NATIONAL ARCHIVES RECORDS RELATING TO THE KOREAN WAR Contents Preface ......................................................................................xi Part I INTRODUCTION SCOPE OF THE PAPER ........................................................................................................................1 OVERVIEW OF THE ISSUES .................................................................................................................1 -

September and October

VIETNAM VETERANS OF AMERICA Office of the National Chaplain LONNIE ABLES - Died Friday, February 6, 2009in Fayetteville, Tennessee at age 60. The cause of death is unknown. He was born October 17, 1948. He was a veteran of the Vietnam War. He was a member of Vietnam Veterans of America – Fayetteville chapter #580. Visitation will be from 5 to 8 p.m. today at Higgins Funeral Home. Funeral services will be at 1 p.m. Monday at the funeral home. CHARLES RANDALL ALDRIDGE – Died Monday, January 26, 2009 at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, DC at the age of 59. He was a resident of Corriganville, Maryland. The cause of death is unknown. He was born October 3, 1949 in Frostburg, Maryland to the late Marcella (Logsdon) Aldridge. In addition to his mother, he was also predeceased by his maternal grandparents, Anna Mae (Bridges) and Marshall Logsdon who helped raise him. He is survived by his loving wife, Susan (Burkett) Aldridge, of the home; his son and daughter-in-law, Randy and Leslie Aldridge, of Cash Valley, Maryland; two daughters, Regina Aldridge, of Australia and Kim Aldridge and her fiancé, John Albright, of Mount Savage, Maryland; five grandchildren, Ryan Aldridge, Ella Sue and Zach Straker, Bailey Ann and Tallon Albright; two sisters and one brother-in-law, Marsha and Barry Phillips and Pam Aldridge; one brother, John Aldridge, and; many other relatives. He served in the United States Marine Corps and was awarded the Purple Heart for wounds sustained in Vietnam. He was a member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars. -

The 108Th Evacuation Hospital Travelogue

1944/1945 Y AN F'vgc.ltep N ica, R E G E F THE 108th EVACUATION HOSPITAL TRAVELOGUE THE FACTS, FIGURES AND SCENES COVERING TEN MONTHS OF OPERATIONS IN THE EUROPEAN THEATRE OF WAR COMPILED AND PUBLISHED THE OFFICERS AND MEN OFTHE 108TH EVACUATION HOSPITAL JUNE 1945 Dedicated to THE COMBAT FORCES OF THE ALLIED NATIONS who stormed the beaches of France and drove the enemy of human liberty into his lair, where they destroyed him. These men suffered and gave their lives, not for an Army or a Nation, but for the principals of decency of mankind. SERVING THEM WAS AN HONOR. IN MEMORIAM RENNES, FRANCE August 1944 TURNER, ORA B. SEX TON, JOHN M. P ATC'A.k ELLO, I, E TT E R I O A. So God loved the world, that he gave his only-begotten Son, to the end that ail that believe in him should not perish, but have everlasting life. St. John m. 16. 2 James E. Yarbrough, Colonel Medical Corps, USA Commanding 3 I wish to express my appreciation to the following members of the 108th in compiling and editing this book: 1st Lt. WALTER R. CHALK Capt. ALANSON HIGBIE Capt. ELLIS JONES 1st Lt. MARGARET T. SADLER (ARC) JANE STEWART (ARC) ISABEL MACGREGOR Pfc FRANK F. BADE Cpl. JAMES H. CAGLE T/Sgt GEORGE E. HUBBARD S/Sgt STEPHEN C. HUDAK Tec 3 RICHARD P. HURLEY Tec 5 PHILIP LA SALA Tec 5 GEORGE E. MICKLE Tec 5 WALTER D. OKRONGLEY Sgt. HARRY RABINOWITZ S/Sgt CLAUDE M. STRANGE Cpl. -

DEPARTMENT of the ARMY the Pentagon, Washington, DC 20310 Phone, 202–545–6700

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY The Pentagon, Washington, DC 20310 Phone, 202±545±6700 SECRETARY OF THE ARMY TOGO D. WEST, JR. Senior Military Assistant COL. T. MICHAEL CREWS Military Assistants COL. ILONA E. PREWITT LT. COL. R. MARK BROWN Aides-de-Camp COL. RANDALL D. BOOKOUT CAPT. CHERYL H. KELLER Assistant to the Secretary PAM JENOFF Under Secretary of the Army JOSEPH R. REEDER Executive to the Under Secretary COL. ROBERT D. GLACEL Military Assistants LT. COL. RALPH BALL, CAPT. RAY BINGHAM, LT. COL. JOHN M. CAL Assistant to the Under Secretary WILLIAM K. TAKAKOSHI Deputy Under Secretary of the Army WALTER W. HOLLIS (Operations Research) Assistant Secretary of the Army (Civil Works) JOHN H. ZIRSCHKY, Acting Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary JOHN H. ZIRSCHKY Executive Officer COL. JOHN A. MILLS Deputy Assistant Secretary for Planning, (VACANCY) Policy and Legislation Deputy Assistant Secretary for Management STEVEN DOLA and Budget Deputy Assistant Secretary for Project ROBERT N. STEARNS Management Assistant for Regulatory Affairs MICHAEL L. DAVIS Assistant for Interagency and International KEVIN V. COOK Affairs Assistant for Water Resources ROBERT J. KAIGHN Assistant Secretary of the Army (Financial HELEN T. MCCOY Management and Comptroller) Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary NEIL R. GINNETTI Executive Officer COL. ROLAND A. ARTEAGA Military Assistant LT. COL. EARL NICKS Deputy Assistant Secretary for Resource ROBERT RAYNSFORD Analysis and Business Practice Deputy Assistant Secretary for Financial ERNEST J. GREGORY Operations Deputy Assistant Secretary for Army Budget MAJ. GEN. ROBERT T. HOWARD Director, US Army Cost and Economic ROBERT W. YOUNG Analysis Center Assistant Secretary of the Army (Installations, ROBERT M. -

A Brief History of the Army Values (As Of: 1 Oct 18)

A Brief History of the Army Values (as of: 1 Oct 18) [T]he most important constant of all-Army values. We must never be complacent about the role of values in our Army. That is why we have made a concerted effort to specify and define the Army values…. Army values are thoroughly consistent with the values of American society. General Dennis Reimer, 33rd Chief of Staff of the Army1 Background The US Army, as America’s land force, promotes national values while defending our national interest. Since its inception in 1775, the US Army has endeavored to instill values within the members of the Army Profession. Guidance from civil authority and military leaders, whether based upon general principle or in response to ethical failures, has attempted to influence both individual and collective values. Through the propagation of laws, codes, regulation, and doctrine they have shaped our shared identity as Army professionals. Beginning in 1981 and clarified in 2012, Army doctrine recognized that the Army Ethic is informed by law, Army Values, beliefs expressed in codes and creeds, and is embedded within our unique Army culture of trust. The moral principles of the Army Ethic and the Army Values inherent within it have always existed and been a point of discussion and honor among the members of the profession. Over the years the Army has repeatedly examined and articulated our individual and institutional values as Army professionals, and we have also continually reviewed and reconsidered our stated and operational values as a profession. This evolving effort continues today. For background on the Army’s past efforts and the evolution of values, our ethic, and character development, please see Information Paper – Analysis of Army’s Past Character Development Efforts – 17 Oct 2016.