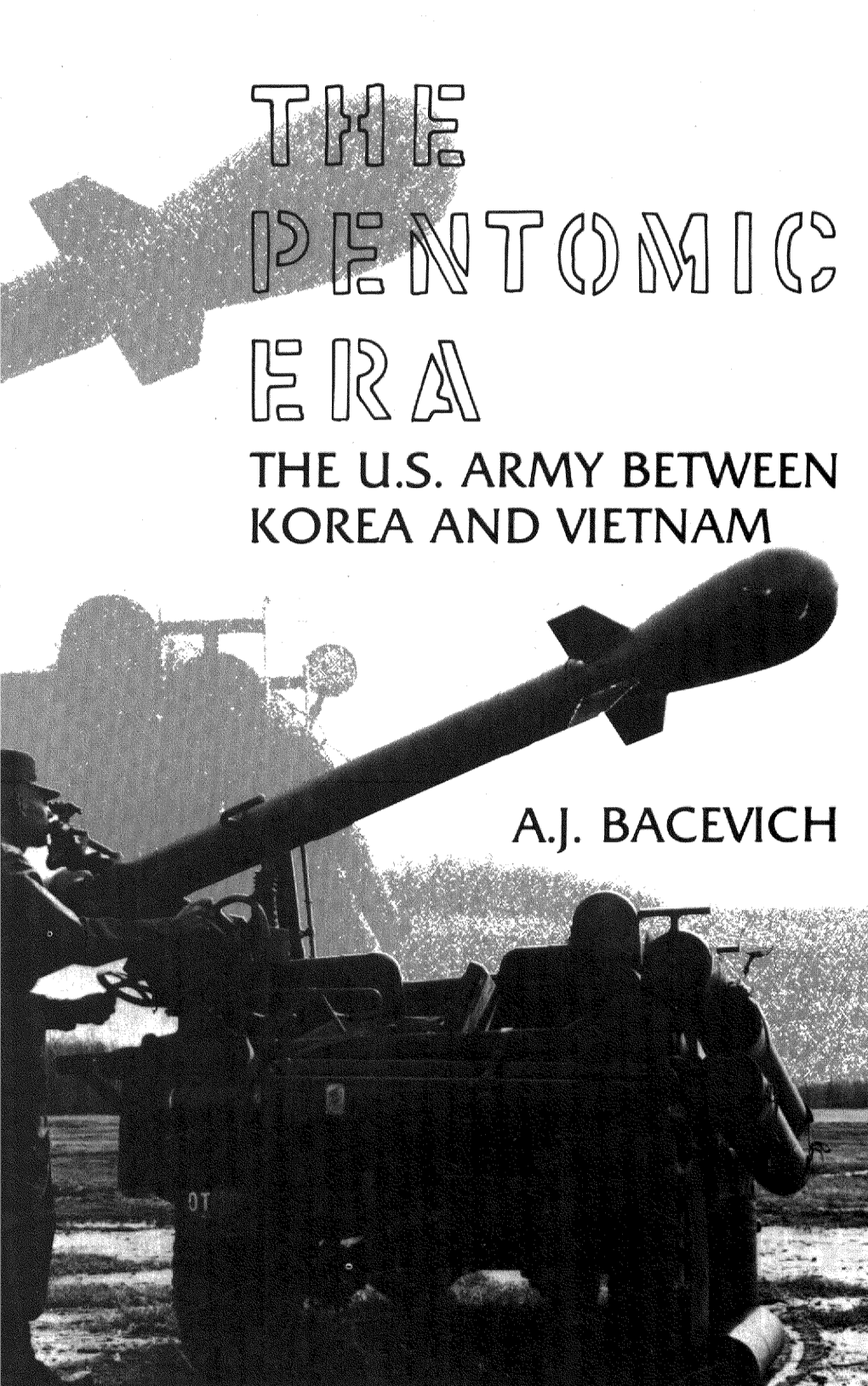

The Pentomic Era: the US Army Between Korea and Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Massive Retaliation Charles Wilson, Neil Mcelroy, and Thomas Gates 1953-1961

Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of MassiveSEPTEMBER Retaliation 2012 Evolution of the Secretary OF Defense IN THE ERA OF Massive Retaliation Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, and Thomas Gates 1953-1961 Special Study 3 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, and Thomas Gates 1953-1961 Cover Photos: Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, Thomas Gates, Jr. Source: Official DoD Photo Library, used with permission. Cover Design: OSD Graphics, Pentagon. Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation Evolution of the Secretary OF Defense IN THE ERA OF Massive Retaliation Charles Wilson, Neil McElroy, and Thomas Gates 1953-1961 Special Study 3 Series Editors Erin R. Mahan, Ph.D. Chief Historian, Office of the Secretary of Defense Jeffrey A. Larsen, Ph.D. President, Larsen Consulting Group Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense September 2012 ii iii Cold War Foreign Policy Series • Special Study 3 Evolution of the Secretary of Defense in the Era of Massive Retaliation Contents Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense, the Historical Office of the Office of Foreword..........................................vii the Secretary of Defense, Larsen Consulting Group, or any other agency of the Federal Government. Executive Summary...................................ix Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. -

Advanced Practice Provider (APRN & PA) Leadership Summit

Hosted by: 12th Annual Advanced Practice Provider (APRN & PA) Leadership Summit September 11 - 14, 2019 Washington DC INTRODUCTION Program Overview The 12th Annual Advanced Practice Provider (APRN & PA) Leadership Summit is a national forum for healthcare leaders and clinicians to share information, develop a consistent platform and map out solutions for universal and reoccurring struggles involving the administrative, managerial, policy and practice aspects of advanced practice providers (advanced practice nursing roles and physician assistants). Continuing Education Attendees will benefit from networking with other healthcare leaders and clinicians and will gain support and resources to enhance advanced practice at their Continuing Education (CE) organizations. Novel strategies and approaches to a Credit: APRNs & RNs variety of advanced practice topics will be shared. Advanced Practice Provider Executives, Interactive discussions with advanced practice leaders will Inc. (APPex) is an approved provider of help attendees learn about state, regional and national continuing nursing education by the challenges, successes and changes. California Board of Registered Nursing (Sacramento, CA). Educational Benefits Provider approved by the California • Network with other healthcare leaders and clinicians Board of Registered Nursing, Provider • Gain support and resources to enhance advanced Number 16233, for 28 contact hours. practice at your organization • Learn novel strategies and approaches to a variety of Continuing Medical advanced practice topics Education (CME) • Learn about state, regional and national challenges, Credit: PAs successes and changes through interactive discussion with advanced practice leaders This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 28 hours of Target Audience AAPA Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. -

Agenda As of 3/9/17

Association of the United States Army Institute of Land Warfare GLOBAL FORCE SYMPOSIUM AND EXPOSITION A Professional Development Forum “Delivering Capabilities for Multi-Domain Battle” 13-15 March 2017 Von Braun Center Huntsville, Alabama NOTE: All participants/speakers/times are subject to change Symposia events take place in the Mark C. Smith Concert Hall, unless otherwise noted SUNDAY, 12 MARCH 2017 1300 – 1700 REGISTRATION (South Hall Foyer) MONDAY, 13 MARCH 2017 0700 – 1830 REGISTRATION (South Hall Foyer) 0700 – 0800 COFFEE SERVICE (Mark C. Smith Concert Hall Foyer) 0800 PRESENTATION OF THE COLORS Lee/New Century JROTC 0800 - 0810 SYMPOSIUM ADMINISTRATION, SAFETY, SECURITY Michael M. Scanlan Senior Director, Meetings Association of the United States Army 0810 - 0820 INTRODUCTION/WELCOME GEN Carter F. Ham United States Army Retired President Association of the United States Army 0820 - 0830 WELCOME TO MADISON/HUNTSVILLE Mayor Tommy Battle Mayor of Huntsville, Alabama 1 Agenda as of 3/9/17 0830 - 0900 TRADOC UPDATE GEN David G. Perkins Commanding General United States Army Training and Doctrine Command 0900 - 0930 ASA(ALT) UPDATE Steffanie B. Easter Acting Assistant Secretary of the Army Acquisition, Logistics and Technology 0930 - 1000 AMC UPDATE GEN Gustave F. Perna Commanding General United States Army Materiel Command 1000 – 1830 EXHIBIT HALL OPEN (South and East Halls) 1000 - 1130 PANEL DISCUSSION Winning in Close Combat: Ground Forces in Multi-Domain Battle Panel Chair: MG Bo Dyess Acting Director Army Capabilities Integration Center United States Army Training and Doctrine Command Panel Moderator: Nina A. Kollars, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Government Franklin & Marshall College Panel Members: Paul Rogers, Ph.D. -

"•"Society Don to Sir Archibald Auldjo Beginning by BETTY BEALE Jamieson

THE EVENING STAR, Washington, D. C. B-7 Mrs. Austin Wed MONDAY. ArFIL IS. IBM In London • ••AAA . EXCLUSIVELY Mrs. Margretta Stroup Aus- tin, formerly of Georgetown, IgP YOURS was married Thursday in Lon- "•"Society don to Sir Archibald Auldjo beginning By BETTY BEALE Jamieson. M.C., K.B.E. Sunday, April 22 Lady Jamieson is. Informa- tion and Cultural Affairs Of- Visiting Canadian Navy Gen. Gruenther Tempted ; ficer in the American Embassy in London She is the daugh- on the occasion of our We will Open Olir doors ter of Mrs. Ner Wallace Starts Wave of Parties Press /or Truman Wedding Stroup of Bethesda and the 11,h Anniversary The story of Gen. Alfred women in journalism will stage sister of Dr. Russell Cartwright Canada's newest antisub- ship are sipping cocktails and for Sunday Dinners Gruenther’s resignation from a big to-do that evening at Stroup, pastor of ,the George- marine destroyer nestled into sampling hors d'oeuvres as guests of and Mrs. supreme command of NATO the Muehlebach Hotel which town Presbyterian Church. a Maine avenue pier this Ambassador • forces and also from the will draw Blevins Davis, Perle Heeney, the crew will be oc- . ,/ from 2 until 10 p.m. | , Sir Archibald Is a director morning, leading quite . nat- cupied with shaking the kinks Army begins with the Presi- Mesta, et al. Blevins will j of Robert Fleming. Invest- / urally in this Nation’s Capital their a /// dent’s heart attack last fall. give a reception Sunday after- ment Bankers, and was, until out of legs at USO Since so many of you hove asked heavy in the YWCA. -

Nuclear Deterrence in the Information Age?

SUMMER 2012 Vol. 6, No. 2 Commentary Our Brick Moon William H. Gerstenmaier Chasing Its Tail: Nuclear Deterrence in the Information Age? Stephen J. Cimbala Fiscal Fetters: The Economic Imperatives of National Security in a Time of Austerity Mark Duckenfield Summer 2012 Summer US Extended Deterrence: How Much Strategic Force Is Too Little? David J. Trachtenberg The Common Sense of Small Nuclear Arsenals James Wood Forsyth Jr. Forging an Indian Partnership Capt Craig H. Neuman II, USAF Chief of Staff, US Air Force Gen Norton A. Schwartz Mission Statement Commander, Air Education and Training Command Strategic Studies Quarterly (SSQ) is the senior United States Air Force– Gen Edward A. Rice Jr. sponsored journal fostering intellectual enrichment for national and Commander and President, Air University international security professionals. SSQ provides a forum for critically Lt Gen David S. Fadok examining, informing, and debating national and international security Director, Air Force Research Institute matters. Contributions to SSQ will explore strategic issues of current and Gen John A. Shaud, PhD, USAF, Retired continuing interest to the US Air Force, the larger defense community, and our international partners. Editorial Staff Col W. Michael Guillot, USAF, Retired, Editor CAPT Jerry L. Gantt, USNR, Retired, Content Editor Disclaimer Nedra O. Looney, Prepress Production Manager Betty R. Littlejohn, Editorial Assistant The views and opinions expressed or implied in the SSQ are those of the Sherry C. Terrell, Editorial Assistant authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, Air Education Editorial Advisors and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or depart- Gen John A. -

Pentagon Salutes Revised Food Courts Options Range from Quick Bites to Sit-Down Dining by BARRY LOBERFELD ASSISTANT EDITOR

FACILITY PROFILE Pentagon Salutes Revised Food Courts Options Range From Quick Bites to Sit-Down Dining BY BARRY LOBERFELD ASSISTANT EDITOR aving completed the last in a seven-year three-stage renova- tion of Pentagon foodservice, the iconic Department of Defense H(DoD) building’s cuisine spans the spectrum from fast food to fi ne dining. Three main food courts comprise the lion’s share of Pentagon food service. Two of the food courts, each offering seating for approximately 250, feature a mélange of branded and non-branded concepts, includ- ing Peruvian Chicken, Taco Bell, McDonald’s, Dunkin’ Donuts, Sbarro and Panda Express, plus clerk-served salad bars and fresh sandwich and Panini stations. The largest food court, the Concourse Food Court, is also the one opened most recently, in September. It is an 875-seat space that houses a Burger King, Subway, Popeyes, Starbucks, RollerZ, Surf City Squeeze and a Dunkin’ Donuts/Baskin-Robbins joint concept. Single-unit food service operations, which are spaces featuring and run by only one business, include a 180-seat Sbarro; the Center Court Café, a 70-seat café located in the middle of the Pentagon’s Center Courtyard; a 40-seat Subway; a 24/7 Dominic’s food service operation; and various cart operations. On Dec. 2, 2009, foodservice renovation plans culminated with the new Pentagon Dining Room opening its doors, introducing a fi ne-dining experience and signaling the work had reached completion. “This facil- ity,” said Jeff Keppler, busi- ness manager/contracting offi cer for the Department of Defense Concessions Committee (DoDCC), “is a 220-seat tablecloth res- taurant that also offers two private function rooms, capable of seating 40 and another with a capacity of 20. -

Warfare in a Fragile World: Military Impact on the Human Environment

Recent Slprt•• books World Armaments and Disarmament: SIPRI Yearbook 1979 World Armaments and Disarmament: SIPRI Yearbooks 1968-1979, Cumulative Index Nuclear Energy and Nuclear Weapon Proliferation Other related •• 8lprt books Ecological Consequences of the Second Ihdochina War Weapons of Mass Destruction and the Environment Publish~d on behalf of SIPRI by Taylor & Francis Ltd 10-14 Macklin Street London WC2B 5NF Distributed in the USA by Crane, Russak & Company Inc 3 East 44th Street New York NY 10017 USA and in Scandinavia by Almqvist & WikseH International PO Box 62 S-101 20 Stockholm Sweden For a complete list of SIPRI publications write to SIPRI Sveavagen 166 , S-113 46 Stockholm Sweden Stoekholol International Peace Research Institute Warfare in a Fragile World Military Impact onthe Human Environment Stockholm International Peace Research Institute SIPRI is an independent institute for research into problems of peace and conflict, especially those of disarmament and arms regulation. It was established in 1966 to commemorate Sweden's 150 years of unbroken peace. The Institute is financed by the Swedish Parliament. The staff, the Governing Board and the Scientific Council are international. As a consultative body, the Scientific Council is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. Governing Board Dr Rolf Bjornerstedt, Chairman (Sweden) Professor Robert Neild, Vice-Chairman (United Kingdom) Mr Tim Greve (Norway) Academician Ivan M£ilek (Czechoslovakia) Professor Leo Mates (Yugoslavia) Professor -

How Should the United States Confront Soviet Communist Expansionism? DWIGHT D

Advise the President: DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER How Should the United States Confront Soviet Communist Expansionism? DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER Advise the President: DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER Place: The Oval Office, the White House Time: May 1953 The President is in the early months of his first term and he recognizes Soviet military aggression and the How Should the subsequent spread of Communism as the greatest threat to the security of the nation. However, the current costs United States of fighting Communism are skyrocketing, presenting a Confront Soviet significant threat to the nation’s economic well-being. President Eisenhower is concerned that the costs are not Communist sustainable over the long term but he believes that the spread of Communism must be stopped. Expansionism? On May 8, 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower has called a meeting in the Solarium of the White House with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and Treasury Secretary George M. Humphrey. The President believes that the best way to craft a national policy in a democracy is to bring people together to assess the options. In this meeting the President makes a proposal based on his personal decision-making process—one that is grounded in exhaustive fact gathering, an open airing of the full range of viewpoints, and his faith in the clarifying qualities of energetic debate. Why not, he suggests, bring together teams of “bright young fellows,” charged with the mission to fully vet all viable policy alternatives? He envisions a culminating presentation in which each team will vigorously advocate for a particular option before the National Security Council. -

The United States Atomic Army, 1956-1960 Dissertation

INTIMIDATING THE WORLD: THE UNITED STATES ATOMIC ARMY, 1956-1960 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paul C. Jussel, B.A., M.M.A.S., M.S.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Advisor Professor John R. Guilmartin __________________ Professor William R. Childs Advisor Department of History ABSTRACT The atomic bomb created a new military dynamic for the world in 1945. The bomb, if used properly, could replace the artillery fires and air-delivered bombs used to defeat the concentrated force of an enemy. The weapon provided the U.S. with an unparalleled advantage over the rest of the world, until the Soviet Union developed its own bomb by 1949 and symmetry in warfare returned. Soon, theories of warfare changed to reflect the belief that the best way to avoid the effects of the bomb was through dispersion of forces. Eventually, the American Army reorganized its divisions from the traditional three-unit organization to a new five-unit organization, dubbed pentomic by its Chief of Staff, General Maxwell D. Taylor. While atomic weapons certainly had an effect on Taylor’s reasoning to adopt the pentomic organization, the idea was not new in 1956; the Army hierarchy had been wrestling with restructuring since the end of World War II. Though the Korean War derailed the Army’s plans for the early fifties, it returned to the forefront under the Eisenhower Administration. The driving force behind reorganization in 1952 was not ii only the reoriented and reduced defense budget, but also the Army’s inroads to the atomic club, formerly the domain of only the Air Force and the Navy. -

Kspreaj Vellow-Red Blend

** EVENING B-18 THE STAR. Washington, D. C. A District vote WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER IS. ISAS iclared. for Pres- Committee agreed last Monday ident and Vice President ¦ Veterans Urged to Unite would I to work, for the right to vote for Concerted not Change the balance in Con- presidential Drive and vice presidential gress and, consequently, would 1 electors. meet congressional Against Future Wars approval, he Mr. Lee said representatives of For Vote Urged added. both parties and other local United action against future The Israeli veterans’ leader j “I can't imagine opposition organizations wars by veterans of all lands A Board of will meet with the saw service in World War II in Trade committee developing in the District of [Boardj of Trade yesterday asked for committee at was advocated here by an Israeli a special Palestine unit of the a community , Columbia to voting like every- jthe next meeting, tentatively set visitor, himself a veteran of two British Army, first in the Suez effort to get the right to vote body else, for President and for November 19. wars. area and the North African for President and Vice Presi- Vice President,” said Mr. War- ner. an attorney. This Meir Bar Rav Hay, a 36-year- campaign, then in Italy as a dent for the people of Washing-; goal ton. lacks financial and technical jGruenther Reports old lawyer from Haifa, and a special unit in the American sth ! This aim was termed problems inherent m seeking member of the Army “practi- executive board under Gen. Mark Clark. cal politics” by Vinton E. -

![[Confirmation Lb713 Lb730 Lb738 Lb797]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4712/confirmation-lb713-lb730-lb738-lb797-684712.webp)

[Confirmation Lb713 Lb730 Lb738 Lb797]

Transcript Prepared By the Clerk of the Legislature Transcriber's Office Health and Human Services Committee January 23, 2008 [CONFIRMATION LB713 LB730 LB738 LB797] The Committee on Health and Human Services met at 1:30 p.m. on Wednesday, January 23, 2008, in Room 1510 of the State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska, for the purpose of conducting a public hearing on gubernatorial appointments, LB713, LB730, LB738, and LB797. Senators present: Joel Johnson, Chairperson; Tim Gay, Vice Chairperson; Philip Erdman; Tom Hansen; Gwen Howard; Dave Pankonin; and Arnie Stuthman. Senators absent: None. [] SENATOR JOHNSON: Thanks very much. Well, let's go ahead and start here this afternoon. I'm Senator Joel Johnson, head of the Health and Human Services Committee, and I don't know whether it was an accident or not, but someone put on my desk up here happy retirement," and this is the last go-round for a few of us around this table. But let's make it a real good session and try and make the world a little bit better for our having been here. Senator Gay, to my right here, is the Vice Chair; beyond him is Senator Pankonin; and then starting off to the left is Senator Howard, Senator Hansen, and Senator Stuthman. We've got Erin Mack and Jeff with us here, who serve as our counsel. And one of the things that we have heard from many people is that we have the best office staff in the building, and I think that's exactly right. So with that, let's go through a few of our ground rules, and they're the same ones as we had before. -

Be a Balladeer

Footsteps for Freedom tm Student lessons along the Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail Be a Balladeer ongs record stories. Sometimes they are history. Sometimes they are just tales worth remembering. S In either case they are made more memorable by putting them to a tune. Long before people in any culture developed writing as a way of Another Memorable Song recording stories, they used songs and ballads as a way of remembering ongs make it easy to remember what is said. events and passing them along. Singing SFind someone in your family or neighborhood the story helped people remember the who would have been your age in the 1960’s. Ask details. The Ballad of Davy Crockett them to sing the theme song from the hit TV show, and the Ballad of John Henry are two “The Beverly Hillbillies.” See if they get all the well-known American stories words. Then ask them how they can remember it remembered in song. The epic tales after all these years. Chances are they’ll say it’s Iliad and Odyssey by the ancient Greek because of the tune, the cadence (that is the beat poet Homer are two of the oldest and pattern of emphasized syllables) and the ballads or poems in Western culture. rhyming that help make it a song. You may know this song yourself if you happen to watch re-runs on A Time to Rhyme television. Sing along! The lyrics to many songs are actually poems. The last words in each line Theme from “The Beverly Hillbillies” often rhyme, though the rhyming Come ‘n listen to my story about a man named Jed, pattern can be different.