Pidgins & Creoles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of Nominal Plural Marking in Zamboanga Chabacano

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 19 Documentation and Maintenance of Contact Languages from South Asia to East Asia ed. by Mário Pinharanda-Nunes & Hugo C. Cardoso, pp.141–173 http:/nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp19 4 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24908 Documenting online writing practices: The case of nominal plural marking in Zamboanga Chabacano Eduardo Tobar Delgado Universidade de Vigo Abstract The emergence of computer-mediated communication has brought about new opportunities for both speakers and researchers of minority or under-described languages. This paper shows how the analysis of spontaneous contemporary language samples from online social networks can make a contribution to the documentation and description of languages like Chabacano, a Spanish-derived creole spoken in the Philippines. More specifically, we focus on nominal plural marking in the Zamboangueño variety, a still imperfectly understood feature, by examining a corpus composed of texts from online sources. The attested combination of innovative and vestigial features requires a close look at the high contact environment, different levels of metalinguistic awareness or even some language ideologies. The findings shed light on the wide variety of plural formation strategies which resulted from the contact of Spanish with Philippine languages. Possible triggers, such as animacy, definiteness or specificity, are also examined and some future research areas suggested. Keywords: nominal plural marking, Zamboangueño Chabacano, number, creole languages Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License 142 Eduardo Tobar Delgado 1. Introduction1 Zamboanga Chabacano (also known as Zamboangueño or Chavacano) is one of the three extant varieties of Philippine Creole Spanish or Chabacano and totals around 500,000 speakers in and around Zamboanga City in the Southern Philippines. -

12 English Dialect Input to the Caribbean

12 English dialect input to the Caribbean 1 Introduction There is no doubt that in the settlement of the Caribbean area by English speakers and in the rise of varieties of English there, the question of regional British input is of central importance (Rickford 1986; Harris 1986). But equally the two other sources of specific features in anglophone varieties there, early creolisation and independent developments, have been given continued attention by scholars. Opinions are still divided on the relative weight to be accorded to these sources. The purpose of the present chapter is not to offer a description of forms of English in the Caribbean – as this would lie outside the competence of the present author, see Holm (1994) for a resum´ e–b´ ut rather to present the arguments for regional British English input as the historical source of salient features of Caribbean formsofEnglish and consider these arguments in the light of recent research into both English in this region and historical varieties in the British Isles. This is done while explicitly acknowledging the role of West African input to forms of English in this region. This case has been argued eloquently and well, since at least Alleyne (1980) whose views are shared by many creolists, e.g. John Rickford. But the aim of the present volume, and specifically of the present chapter, is to consider overseas varieties of English in the light of possible continuity of input formsofEnglish from the British Isles. This concern does not seek to downplay West African input and general processes of creolisation, which of course need to be specified in detail,1 butrather tries to put the case for English input and so complement other views already available in the field. -

Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure

LINGUISTICS - Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure PIDGINS AND CREOLES Genevieve Escure Department of English, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA Keywords: contact language, lingua franca, (post)creole continuum, basilect, mesolect, acrolect, substrate, superstrate, bioprogram, monogenesis, polygenesis, relexification, variability, code switching, covert prestige, overt prestige, colonization, identity, nativization. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Some general properties of pidgins and creoles 3. Pidgins: Incipient communication 3.1. Chinese Pidgin English 3.2. Russenorsk. 3.3. Hawaiian Pidgin English 4. Creoles: Expansion, stabilization and variability 4.1. Basilect 4.2. Acrolect 4.3. Mesolect 5. Theoretical models and current trends in PC studies 5.1. Early models 5.2. Developments of the substratist position 5.3. Developments of the universalist position: The bioprogram 6. The (post)creole continuum and decreolization 7. New trends 7.1. Sociohistorical evidence 7.2. Demographic explanations 7.3. Acquisition 8. Conclusion Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch UNESCO – EOLSS Summary Pidgins and creolesSAMPLE are languages that arose CHAPTERSin the context of temporary events (e.g., trade, seafaring, and even tourism), or enduring traumatic social situations such as slavery or wars. In the latter context, subjugated people were forced to create new languages for communication. Long stigmatized, those languages provide valuable insight into the mental mechanisms that enable individuals to use their innate capacity -

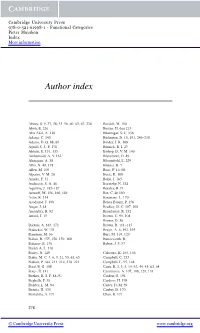

Author Index

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-61998-1 - Functional Categories Pieter Muysken Index More information Author index Abney, S. 9, 37, 38, 53–56, 60–63, 67, 228 Bersick, M. 108 Aboh, E. 226 Besten, H. den 213 Abu-Akel, A. 116 Bhatnagar, S. C. 136 Adams, C. 140 Bickerton, D. 10, 191, 246–250 Adams, D. Q. 88, 89 Binder, J. R. 108 Aguil´oS. J., F. 178 Binnick, R. I. 23 Ahls´en,E. 131, 135 Bishop, D. V. M. 140 Aikhenvald, A. Y. 162 Blakemore, D. 49 Akmajian, A. 58 Bloomfield, L. 229 Alb´o,X. 49, 178 Blutner, R. 7 Allen, M. 109 Boas, F. 14, 60 Alpatov, V. M. 28 Bock, K. 100 Ameka, F. 51 Bolle, J. 163 Anderson, S. A. 46 Boretzky, N. 224 Aquilina, J. 185–187 Borsley, R. D. Aronoff, M. 156, 160, 184 Bot, C. de 150 Aslin, R. 114 Boumans, L. 170 Asodanoe, J. 198 Boyes Braem, P. 156 Auger, J. 48 Bradley, D. C. 107, 108 Austerlitz, R. 92 Broadaway, R. 232 Award, J. 15 Brown, C. 99, 108 Brown, D. 36 Backus, A. 164, 172 Brown, R. 111–115 Badecker, W. 131 Bruyn, A. 6, 192, 193 Baerman, M. 36 Burt, M. 119, 120 Bahan, B. 155, 156, 159, 160 Butterworth, B. Baharav, E. 136 Bybee, J. 3, 57 Bailey A. L. 116 Bailey, N. 120 Calteaux, K. 165, 166 Baker, M. C. 4, 6, 9, 21, 53, 61, 65 Campbell, C. 233 Bakker, P. 184, 211–214, 218–221 Campbell, L. 95, 144 Bard, E. G. -

Making Sense of "Bad English"

MAKING SENSE OF “BAD ENGLISH” Why is it that some ways of using English are considered “good” and others are considered “bad”? Why are certain forms of language termed elegant, eloquent, or refined, whereas others are deemed uneducated, coarse, or inappropriate? Making Sense of “Bad English” is an accessible introduction to attitudes and ideologies towards the use of English in different settings around the world. Outlining how perceptions about what constitutes “good” and “bad” English have been shaped, this book shows how these principles are based on social factors rather than linguistic issues and highlights some of the real-life consequences of these perceptions. Features include: • an overview of attitudes towards English and how they came about, as well as real-life consequences and benefits of using “bad” English; • explicit links between different English language systems, including child’s English, English as a lingua franca, African American English, Singlish, and New Delhi English; • examples taken from classic names in the field of sociolinguistics, including Labov, Trudgill, Baugh, and Lambert, as well as rising stars and more recent cutting-edge research; • links to relevant social parallels, including cultural outputs such as holiday myths, to help readers engage in a new way with the notion of Standard English; • supporting online material for students which features worksheets, links to audio and news files, further examples and discussion questions, and background on key issues from the book. Making Sense of “Bad English” provides an engaging and thought-provoking overview of this topic and is essential reading for any student studying sociolinguistics within a global setting. -

Anala Lb. Straine 2016 Nr.1

ANALELE UNIVERSITĂŢII BUCUREŞTI LIMBI ŞI LITERATURI STRĂINE 2016 – Nr. 1 SUMAR • SOMMAIRE • CONTENTS LINGVISTIC Ă / LINGUISTIQUE / LINGUISTICS ELENA L ĂCĂTU Ş, Romanian Aspectual Verbs: Control and Restructuring ............... 3 COSTIN-VALENTIN OANCEA, The Category of Number in Present-Day English(es): Variation and Context ............................................................................................ 25 LEAH NACHMANI, EFL Teachers’ Perspectives on Reading Acquisition within a Multi-Cultural Learning Environment .................................................................. 41 ANDREI A. AVRAM, Diagnostic Features of English Pidgins/Creoles: New Evidence from West African Pidgin English and Krio ........................................................ 55 MIHAI CRUDU, Zum Lexem Herr und zu dessen Auftauchen in Wortbildungen und Phrasemen ............................................................................................................... 79 CAMELIA M ĂDĂLINA ŞTEFAN, On Latin-Old Swedish Language Contact through Loanwords ............................................................................................................... 89 * Recenzii • Comptes rendus • Reviews .................................................................................. 105 Contributors ........................................................................................................................ 111 ROMANIAN ASPECTUAL VERBS: CONTROL AND RESTRUCTURING ELENA L ĂCĂTU Ş* Abstract The aim of the present paper is to investigate -

Journal of Postcolonial Writing the Field of Pidgin

This article was downloaded by: [Stanford University] On: 3 June 2011 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 731786911] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Postcolonial Writing Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713735330 The field of Pidgin-Creole studies: A review article on Loreto Todd's Pidgins and Creoles. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1974 John Rickforda a University of Guyana, To cite this Article Rickford, John(1977) 'The field of Pidgin-Creole studies: A review article on Loreto Todd's Pidgins and Creoles. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1974', Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 16: 2, 477 — 513 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/17449857708588494 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17449857708588494 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 7 Issue 3 Papers from NWAV 29 Article 20 2001 A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos Peter Snow Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Snow, Peter (2001) "A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 7 : Iss. 3 , Article 20. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol7/iss3/20 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol7/iss3/20 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos This working paper is available in University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol7/iss3/20 A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos 1 Peter Snow 1 Introduction In its ideal form, the phenomenon of the creole continuum as originally described by DeCamp (1971) and Bickerton (1973) may be understood as a result of the process of decreolization that occurs wherever a creole is in direct contact with its lexifier. This contact between creole languages and the languages that provide the majority of their lexicons leads to synchronic variation in the form of a continuum that reflects the unidirectional process of decreolization. The resulting continuum of varieties ranges from the "basilect" (most markedly creole), through intermediate "mesolectal" varie ties (less markedly creole), to the "acrolect" (least markedly creole or the lexifier language itself). -

Describing Creole: Researcher Perspectives on Endangerment and Multilingualism in the Chabacano Communities

Describing creole: researcher perspectives on endangerment and multilingualism in the Chabacano communities Eeva Sippola University of Helsinki This paper discusses perspectives on language description and endangerment in creole communities, with a special focus on Chabacano-speaking communities in the Philippines. I will show how, from the early days of research on these varieties, linguists with an interest in Chabacano often present the varieties under study as endangered in a moribund state or aim to describe a ‘pure’ Chabacano system without Philippine or English influences, silencing a great deal of the daily multilingualism and hybrid language practices that have always been present in the communities. In general, this paper sheds light on the complex dynamics of discourses on endangerment and authenticity in research about multilingual communities. It also contributes to the discussion on how these types of contexts challenge common Western assumptions about language loss and on authenticity in multilingual communities. Keywords: Chabacano, linguistic research, ideology, authenticity, multilingual communities. 1. Introduction This paper examines practices and ideologies of language description and documentation in the Chabacano-speaking communities in the Philippines. Chabacano is the common name used for creole varieties that have Spanish as the lexifier and Philippine languages as the adstrates and that have historically been spoken in several locations in the Philippines. There is documentation of varieties in Zamboanga, Cotabato, and Davao in Mindanao in the southern Philippines, and in the Ermita district of Manila, Cavite City, and Ternate in the Manila Bay region of the northern island of Luzon. They are for the most part mutually intelligible, but there are sociohistorical circumstances and linguistic differences that distinguish them (Lesho & Sippola 2013, 2014). -

Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity

Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity Karen Mattison Yabuno I. INTRODUCTION Hawaiian Creole English, commonly known as Pidgin, is widely spoken in Hawaii. In 2015, it was recognized by the US Census Bureau as a third official language of Hawaii, following English and Hawaiian(Laddaran, 2015). Pidgin is distinct and separate from Hawaii English(Drager, 2012), which is also widely spoken in Hawaii but not recognized as an official language of the state. Pidgin arose among immigrant groups on the pineapple plantations and was the dominant language of the workers’ children by the 1920’s(Tamura, 1993). Historically, an ability to speak Pidgin established one as ‘local’ to Hawaii, while English was seen to be part of the haole(Caucasian) identity (Drager, 2012). Although non-English speaking Caucasians also worked on the plantations, the term ‘local’ has come to mean those descended from Asian immigrant groups, as well as indigenous Hawaiians. These days, about half of the population of Hawaii speak Pidgin(Sakoda and Siegel, 2003). Caucasians born, raised, or residing in Hawaii may also understand and speak Pidgin. However, there can be a negative reaction to Caucasians speaking Pidgin, even when the Caucasians self-identify as ‘locals’. This is discussed in the YouTube video, Being White in Hawaii(Timahification, 2014), and parodied in the YouTube video, Hawaiian Haole(YouRight, 2016). Why is it offensive for a Caucasian to speak Pidgin? To answer this question, this paper will examine the parody video, Hawaiian Haole; ‘local’ ―189― Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity identity in Hawaii; and race in Hawaii. Finally, the viewpoints of three ‘local’ haole will be presented. -

Nominal Contact in Michif. by Carrie Gillon and Nicole Rosen , with Verna De - Montigny

806 LANGUAGE, VOLUME 9 5, NUMBER 4 (201 9) Corbett, Greville G. 2009. Canonical inflection classes. Selected proceedings of the 6th Décembrettes , ed. by Fabio Montermini, Gilles Boyé, and Jessie Tseng, 1–11. Online: http://www.lingref.com/cpp/decemb /6/paper2231.pdf . Dahl, Östen . 2004. The growth and maintenance of linguistic complexity . Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Harley, Heidi. 2008. When is a syncretism more than a syncretism? Impoverishment, metasyncretism, and underspecification. Phi theory: Phi-features across modules and interfaces , ed. by Daniel Harbour, David Adger, and Susana Béjar, 251–94. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Parker, Jeff, and Andrea D. Sims. 2020. Irregularity, paradigmatic layers, and the complexity of inflection class systems: A study of Russian nouns. Morphological complexities , ed. by Peter Arkadiev and Francesco Gardani. Oxford: Oxford University Press, to appear. Sagot, Benoît, and Géraldine Walther. 2011 . Non-canonical inflection: Data, formalisation and com - plexity measures. SFCM 2011: The second workshop on Systems and Frameworks for Computational Morphology , ed. by Cerstin Mahlow and Michael Piotrowski, 23–45. Berlin: Springer. Stump, Gregory T . 2016. Inflectional paradigms: Content and form at the syntax-morphology interface . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Zwicky, Arnold M. 1992. Some choices in the theory of morphology. Formal grammar: Theory and imple - mentation , ed. by Robert Levine, 327–71. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Department of Linguistics 1712 Neil Avenue Columbus, OH 43210 [[email protected]] Nominal contact in Michif. By Carrie Gillon and Nicole Rosen , with Verna De - montigny . (Oxford studies of endangered languages.) Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. Pp. xxii, 202. ISBN 9780198795339. $88 (Hb). Reviewed by Sarah G. -

Pidgins and Creoles

12/7/2015 LNGT0101 Announcements Introduction to Linguistics • HW 4 sent to your inboxes. Average score is 45/50. • Final HW is due today, and then you can celebrate. • Any questions on your final papers? Lecture #23 Dec 7th, 2015 2 Announcements Word play! • I’ll give out course response forms on Wednesday. So, please be there to fill them out! • Photo today? 3 4 Ambiguity again! Today’s agenda • Discussion of pidgins and creoles. 5 6 1 12/7/2015 Language contact What is a pidgin? Creating language out of thin air: What is a creole? The case of Pidgins and Creoles 7 8 Origin of Hawaiian Pidgin A sample of Hawaiian Pidgin • http://sls.hawaii.edu/pidgin/whatIsPidgin.php • http://www.mauimagazine.net/Maui‐ Magazine/July‐August‐2015/Da‐State‐of‐da‐ State/ 9 10 How about we listen to this English‐based speech variety? • English‐based speech variety • How much did you understand? • Maybe we can try reading. Not sure it’ll help, but let’s try. 11 12 2 12/7/2015 Emergence of Pidgins and Creoles Pidginization areas • A pidgin is a system of communication used by people who do not know each other’s languages but need to communicate with one another for trading or other purposes. • By definition, then, a pidgin is not a natural language. It’s a made‐up “makeshift” language. Notice, crucially, that it does not have native speakers. 13 14 The lexicons of Pidgins are typically based Pidgins are linguistically on some dominant language simplified systems • While a pidgin is used by speakers of different • As you should expect, pidgins are very simple languages, it is typically based on the lexicon of what in their linguistic properties.