Origin and Phylogenetic Relationships of Living Amphibians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha)

Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha) by Richard Kissel A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy Graduate Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology University of Toronto © Copyright by Richard Kissel 2010 Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha) Richard Kissel Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology University of Toronto 2010 Abstract Based on dental, cranial, and postcranial anatomy, members of the Permo-Carboniferous clade Diadectidae are generally regarded as the earliest tetrapods capable of processing high-fiber plant material; presented here is a review of diadectid morphology, phylogeny, taxonomy, and paleozoogeography. Phylogenetic analyses support the monophyly of Diadectidae within Diadectomorpha, the sister-group to Amniota, with Limnoscelis as the sister-taxon to Tseajaia + Diadectidae. Analysis of diadectid interrelationships of all known taxa for which adequate specimens and information are known—the first of its kind conducted—positions Ambedus pusillus as the sister-taxon to all other forms, with Diadectes sanmiguelensis, Orobates pabsti, Desmatodon hesperis, Diadectes absitus, and (Diadectes sideropelicus + Diadectes tenuitectes + Diasparactus zenos) representing progressively more derived taxa in a series of nested clades. In light of these results, it is recommended herein that the species Diadectes sanmiguelensis be referred to the new genus -

Early Tetrapod Relationships Revisited

Biol. Rev. (2003), 78, pp. 251–345. f Cambridge Philosophical Society 251 DOI: 10.1017/S1464793102006103 Printed in the United Kingdom Early tetrapod relationships revisited MARCELLO RUTA1*, MICHAEL I. COATES1 and DONALD L. J. QUICKE2 1 The Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy, The University of Chicago, 1027 East 57th Street, Chicago, IL 60637-1508, USA ([email protected]; [email protected]) 2 Department of Biology, Imperial College at Silwood Park, Ascot, Berkshire SL57PY, UK and Department of Entomology, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW75BD, UK ([email protected]) (Received 29 November 2001; revised 28 August 2002; accepted 2 September 2002) ABSTRACT In an attempt to investigate differences between the most widely discussed hypotheses of early tetrapod relation- ships, we assembled a new data matrix including 90 taxa coded for 319 cranial and postcranial characters. We have incorporated, where possible, original observations of numerous taxa spread throughout the major tetrapod clades. A stem-based (total-group) definition of Tetrapoda is preferred over apomorphy- and node-based (crown-group) definitions. This definition is operational, since it is based on a formal character analysis. A PAUP* search using a recently implemented version of the parsimony ratchet method yields 64 shortest trees. Differ- ences between these trees concern: (1) the internal relationships of aı¨stopods, the three selected species of which form a trichotomy; (2) the internal relationships of embolomeres, with Archeria -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE AMY C. HENRICI Collection Manager Section of Vertebrate Paleontology Carnegie Museum of Natural History 4400 Forbes Avenue Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213-4080, USA Phone:(412)622-1915 Email: [email protected] BACKGROUND Birthdate: 24 September 1957. Birthplace: Pittsburgh. Citizenship: USA. EDUCATION B.A. 1979, Hiram College, Ohio (Biology) M.S. 1989, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (Geology) CAREER Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) Laboratory Technician, Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1979 Research Assistant, Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1980 Curatorial Assistant, Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1980-1984 Scientific Preparator, Section of Paleobotany, 1985-1986 Scientific Preparator, Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1985-2002 Acting Collection Manager/Scientific Preparator, 2003-2004 Collection Manager, 2005-present PALEONTOLOGICAL FIELD EXPERIENCE Late Pennsylvanian through Early Permian of Colorado, New Mexico and Utah (fish, amphibians and reptiles) Early Permian of Germany, Bromacker quarry (amphibians and reptiles) Triassic of New Mexico, Coelophysis quarry (Coelophysis and other reptiles) Upper Jurassic of Colorado (mammals and herps) Tertiary of Montana, Nevada, and Wyoming (mammals and herps) Pleistocene of West Virginia (mammals and herps) Lake sediment cores and lake sediment surface samples, Wyoming (pollen and seeds) PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS Associate Editor, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1998-2000. Research Associate in the Science Division, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, 2007-present. PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATIONS Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paleontological Society LECTURES and TUTORIALS (Invited and public) 1994. Middle Eocene frogs from central Wyoming: ontogeny and taphonomy. California State University, San Bernardino 1994. Mechanical preparation of vertebrate fossils. California State University, San Bernardino 1994. Mechanical preparation of vertebrate fossils. University of Chicago 2001. -

Physical and Environmental Drivers of Paleozoic Tetrapod Dispersal Across Pangaea

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07623-x OPEN Physical and environmental drivers of Paleozoic tetrapod dispersal across Pangaea Neil Brocklehurst1,2, Emma M. Dunne3, Daniel D. Cashmore3 &Jӧrg Frӧbisch2,4 The Carboniferous and Permian were crucial intervals in the establishment of terrestrial ecosystems, which occurred alongside substantial environmental and climate changes throughout the globe, as well as the final assembly of the supercontinent of Pangaea. The fl 1234567890():,; in uence of these changes on tetrapod biogeography is highly contentious, with some authors suggesting a cosmopolitan fauna resulting from a lack of barriers, and some iden- tifying provincialism. Here we carry out a detailed historical biogeographic analysis of late Paleozoic tetrapods to study the patterns of dispersal and vicariance. A likelihood-based approach to infer ancestral areas is combined with stochastic mapping to assess rates of vicariance and dispersal. Both the late Carboniferous and the end-Guadalupian are char- acterised by a decrease in dispersal and a vicariance peak in amniotes and amphibians. The first of these shifts is attributed to orogenic activity, the second to increasing climate heterogeneity. 1 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3AN, UK. 2 Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz-Institut für Evolutions- und Biodiversitätsforschung, Invalidenstraße 43, 10115 Berlin, Germany. 3 School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK. 4 Institut -

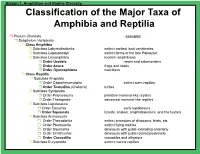

Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia

Station 1. Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia ! Phylum Chordata examples ! Subphylum Vertebrata ! Class Amphibia ! Subclass Labyrinthodontia extinct earliest land vertebrates ! Subclass Lepospondyli extinct forms of the late Paleozoic ! Subclass Lissamphibia modern amphibians ! Order Urodela newts and salamanders ! Order Anura frogs and toads ! Order Gymnophiona caecilians ! Class Reptilia ! Subclass Anapsida ! Order Captorhinomorpha extinct stem reptiles ! Order Testudina (Chelonia) turtles ! Subclass Synapsida ! Order Pelycosauria primitive mammal-like reptiles ! Order Therapsida advanced mammal-like reptiles ! Subclass Lepidosaura ! Order Eosuchia early lepidosaurs ! Order Squamata lizards, snakes, amphisbaenians, and the tuatara ! Subclass Archosauria ! Order Thecodontia extinct ancestors of dinosaurs, birds, etc ! Order Pterosauria extinct flying reptiles ! Order Saurischia dinosaurs with pubis extending anteriorly ! Order Ornithischia dinosaurs with pubis rotated posteriorly ! Order Crocodilia crocodiles and alligators ! Subclass Euryapsida extinct marine reptiles Station 1. Amphibian Skin AMPHIBIAN SKIN Most amphibians (amphi = double, bios = life) have a complex life history that often includes aquatic and terrestrial forms. All amphibians have bare skin - lacking scales, feathers, or hair -that is used for exchange of water, ions and gases. Both water and gases pass readily through amphibian skin. Cutaneous respiration depends on moisture, so most frogs and salamanders are -

Early Tetrapod Evolution: Red Queen Or Court Jester?

Early tetrapod evolution: Red Queen or Court Jester? Supervisors: Prof Mike Benton (School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol) – Main supervisor Dr Marcello Ruta (School of Life Sciences, University of Lincoln) Dr Alex Dunhill (Department of Biology and Biochemistry, University of Bath) Host Institution: University of Bristol Project description: In a Red Queen world, intrinsic factors that regulate biodiversity include body size, breadth of physiological tolerance, or adaptability to hard times. In a Court Jester world, species diversity depends on fluctuations in climate, landscape, and food supply. In reality, of course, both aspects might prevail in different ways and at different times. Behind the colourful allegories is a very simple, and yet key, question: are major differences in clade biodiversity driven by innate characteristics such as key adaptations/ innovations or by the chances of external crises and opportunities? Early tetrapods provide an excellent case study to explore large-scale adaptive radiations and environmental crises. The project will start with an existing database on early tetrapods (Benton et al. 2013), develop and improve this, and then explore key events. The database currently comprises 1388 valid genera, of which 391 are classed as ‘Amphibia’ (namely stem-tetrapods, Temnospondyli, Lepospondyli, Reptiliomorpha, Lissamphibia) and 997 as Amniota. The focus of the research will be on key events, primarily clade origins and expansions (‘adaptive radiations’) and mass extinctions. The two primary questions are (a) do adaptive radiations differ from diversifications following mass extinctions, and (b) how much biodiversity at certain times can be attributed to intrinsic factors and how much to extrinsic? Benton, M.J., Ruta, M., Dunhill, A.M., and Sakamoto, M. -

Early Vertebrate Evolution New Insights Into the Morphology of the Carboniferous Tetrapod Crassigyrinus Scoticus from Computed Tomography Eva C

Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 109, 157–175, 2019 (for 2018) Early Vertebrate Evolution New insights into the morphology of the Carboniferous tetrapod Crassigyrinus scoticus from computed tomography Eva C. HERBST* and John R. HUTCHINSON Structure and Motion Laboratory, Department of Comparative Biomedical Sciences, Royal Veterinary College, University of London, Hatfield, Hertfordshire AL9 7TA, UK. Email: [email protected] *Corresponding author ABSTRACT: The Carboniferous tetrapod Crassigyrinus scoticus is an enigmatic animal in terms of its morphology and its phylogenetic position. Crassigyrinus had extremely reduced forelimbs, and was aquatic, perhaps secondarily. Recent phylogenetic analyses tentatively place Crassigyrinus close to the whatcheeriids. Many Carboniferous tetrapods exhibit several characteristics associated with terrestrial locomotion, and much research has focused on how this novel locomotor mode evolved. However, to estimate the selective pressures and constraints during this important time in vertebrate evolution, it is also important to study early tetrapods like Crassigyrinus that either remained aquatic or secondarily became aquatic. We used computed tomographic scanning to search for more data about the skeletal morphology of Crassigyrinus and discovered several elements previously hidden by the matrix. These elements include more ribs, another neural arch, potential evidence of an ossified pubis and maybe of pleurocentra. We also discovered several additional metatarsals with interesting asymmetrical morphology that may have functional implications. Finally, we reclassify what was previously thought to be a left sacral rib as a left fibula and show previously unknown aspects of the morphology of the radius. These discoveries are examined in functional and phylogenetic contexts. KEY WORDS: evolution, palaeontology, phylogeny, water-to-land transition. -

Was Mesosaurus a Fully Aquatic Reptile?

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 27 July 2018 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2018.00109 Was Mesosaurus a Fully Aquatic Reptile? Pablo Nuñez Demarco 1,2*, Melitta Meneghel 3, Michel Laurin 4 and Graciela Piñeiro 5* 1 Facultad de Ciencias, Instituto de Ciencias Geológicas, Universidad de la República, Montevideo, Uruguay, 2 Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, InGeBa, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 3 Laboratorio de Sistemática e Historia Natural de Vertebrados, Facultad de Ciencias, IECA, Universidad de la República, Montevideo, Uruguay, 4 CR2P, UMR 7207, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique/MNHN/UPMC, Sorbonne Universités, Paris, France, 5 Departamento de Paleontología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de la República, Montevideo, Uruguay Mesosaurs have been considered strictly aquatic animals. Their adaptations to the aquatic environment are well known and include putative viviparity, along with the presence of several skeletal characters such as a long, laterally compressed tail, long limbs, the foot larger than the manus, and presence of pachyosteosclerotic bones. They were also described as possessing non-coossified girdle bones and incompletely ossified epiphyses, although there could be an early fusion of the front girdle bones to form the scapulocoracoid in some specimens. Some of these features, however, are shared by most basal tetrapods that are considered semiaquatic and even some terrestrial ones. The study of vertebral columns and limbs provides essential clues about the locomotor Edited by: system and the lifestyle of early amniotes. In this study, we have found that the variation of Martin Daniel Ezcurra, the vertebral centrum length along the axial skeleton of Mesosaurus tenuidens fits better Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales Bernardino Rivadavia, with a semi-aquatic morphometric pattern, as shown by comparisons with other extinct Argentina and extant taxa. -

Angela Milner Keraterpeton.Pdf

Title A morphological revision of Keraterpeton, the earliest horned nectridean from the Pennsylvanian of England and Ireland. Authors Milner, Angela Date Submitted 2020-02-07 Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh A morphological revision of the earliest horned nectridean from the Pennsylvanian of England and Ireland Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Journal: Edinburgh Manuscript ID Draft Manuscript Type: Early Vertebrate Evolution Date Submitted by the Author: n/a Complete List of Authors: Milner, Angela; The Natural History Museum, Earth Sceinces For<i>Keraterpeton</i>, Peer Review anatomy, evolution, functional morphology, Keywords: systematics Cambridge University Press Page 1 of 43 Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1 A morphological revision of the earliest horned nectridean from the Pennsylvanian of England and Ireland Angela C. Milner Department of Earth Sciences The Natural History Museum Cromwell Road London SW7 5BD [email protected] Running head For Peer Review Keraterpeton from the Pennsylvanian of England and Ireland Cambridge University Press Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Page 2 of 43 2 ABSTRACT The aquatic diplocaulid nectridean Keraterpeton galvani, is the commonest taxon represented in the Jarrow Coal assemblage from Kilkenny, Ireland. The Jarrow locality has yielded the earliest known Carboniferous coal-swamp fauna in the fossil record and is therefore of importance in understanding the history and diversity of the diplocaulid clade. The morphology of Keraterpeton is described in detail with emphasis on newly observed anatomical features. A reconstruction of the palate includes the presence of interpterygoid vacuities andnew morphological details of the pterygoid, parasphenoid and basicranial region. -

Neosaurus Cynodus, and Related Material, from the Permo-Carboniferous of France

The sphenacodontid synapsid Neosaurus cynodus, and related material, from the Permo-Carboniferous of France JOCELYN FALCONNET Falconnet, J. 2015. The sphenacodontid synapsid Neosaurus cynodus, and related material, from the Permo-Carbonifer- ous of France. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 60 (1): 169–182. Sphenacodontid synapsids were major components of early Permian ecosystems. Despite their abundance in the North American part of Pangaea, they are much rarer in Europe. Among the few described European taxa is Neosaurus cynodus, from the La Serre Horst, Eastern France. This species is represented by a single specimen, and its validity has been ques- tioned. A detailed revision of its anatomy shows that sphenacodontids were also present in the Lodève Basin, Southern France. The presence of several synapomorphies of sphenacodontids—including the teardrop-shaped teeth—supports the assignment of the French material to the Sphenacodontidae, but it is too fragmentary for more precise identification. The discovery of sphenacodontids in the Viala Formation of the Lodève Basin provides additional information about their ecological preferences and environment, supporting the supposed semi-arid climate and floodplain setting of this formation. The Viala vertebrate assemblage includes aquatic branchiosaurs and xenacanthids, amphibious eryopoids, and terrestrial diadectids and sphenacodontids. This composition is very close to that of the contemporaneous assemblages of Texas and Oklahoma, once thought to be typical of North American lowland deposits, and thus supports the biogeo- graphic affinities of North American and European continental early Permian ecosystems. Key words: Synapsida, Sphenacodontidae, anatomy, taxonomy, ecology, Carboniferous, Permian, France. Jocelyn Falconnet [[email protected]], CR2P UMR 7207, MNHN, UPMC, CNRS, Département Histoire de la Terre, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, CP 38, 57 rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris Cedex 05, France. -

Stem Caecilian from the Triassic of Colorado Sheds Light on the Origins of Lissamphibia

Stem caecilian from the Triassic of Colorado sheds light PNAS PLUS on the origins of Lissamphibia Jason D. Pardoa, Bryan J. Smallb, and Adam K. Huttenlockerc,1 aDepartment of Comparative Biology and Experimental Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2N 4N1; bMuseum of Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79415; and cDepartment of Integrative Anatomical Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089 Edited by Neil H. Shubin, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, and approved May 18, 2017 (received for review April 26, 2017) The origin of the limbless caecilians remains a lasting question in other early tetrapods; “-ophis” (Greek) meaning serpent. The vertebrate evolution. Molecular phylogenies and morphology species name honors paleontologist Farish Jenkins, whose work on support that caecilians are the sister taxon of batrachians (frogs the Jurassic Eocaecilia inspired the present study. and salamanders), from which they diverged no later than the early Permian. Although recent efforts have discovered new, early Holotype. Denver Museum of Nature & Science (DMNH) 56658, members of the batrachian lineage, the record of pre-Cretaceous partial skull with lower jaw and disarticulated postcrania (Fig. 1 caecilians is limited to a single species, Eocaecilia micropodia. The A–D). Discovered by B.J.S. in 1999 in the Upper Triassic Chinle position of Eocaecilia within tetrapod phylogeny is controversial, Formation (“red siltstone” member), Main Elk Creek locality, as it already acquired the specialized morphology that character- Garfield County, Colorado (DMNH loc. 1306). The tetrapod as- izes modern caecilians by the Jurassic. Here, we report on a small semblage is regarded as middle–late Norian in age (Revueltian land amphibian from the Upper Triassic of Colorado, United States, with vertebrate faunachron) (13). -

(Lepospondyli: Nectridea) Ze Svrchního Karbonu Lokality Nýřany, Česká Republika

PŘÍRODOVĚDECKÁ FAKULTA Redeskripce druhu Sauropleura scalaris (Lepospondyli: Nectridea) ze svrchního karbonu lokality Nýřany, Česká republika Rešerše k diplomové práci Pavel Barták Vedoucí práce: doc. Mgr. Martin Ivanov, Dr. Ústav geologických věd Obsah Úvod ............................................................................................................................... 3 Lokality svrchnokarbonského stáří České republiky s doklady skupin Temnospondyli Zittel, 1888 a Lepospondyli Zittel, 1888 .......................................... 3 Nýřany ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Třemošná ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Kounov ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Systematika svrchnokarbonských tetrapodů: Lepospondyli Zittel, 1888 & Temnospondyli Zittel, 1888 .......................................................................................... 8 Lepospondyli Zittel, 1888 .................................................................................................................... 8 Temnospondyli Zittel, 1888 ................................................................................................................. 9 Chronologický přehled výzkumů bazálních tetrapodů ze svrchního