Title: FossilFocus—TheEcologyAnd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 07:16:35PM Via Free Access 278 H.-P

Contributions to Zoology, 67 (4) 277-279 (1998) SPB Academic Publishing bv, Amsterdam Short notes and reviews The fossil fauna of Mazon Creek Hans-Peter Schultze Institutfür Paläontologie, Museum für Naturkunde, Invalidenstr. 43, D-10115 Berlin, Germany Keywords: Book review, Mazon Creek, fossil fauna Review of: Richardson’s Guide to the Fossil tematic collecting effort that tried to match that of Fauna of Mazon Creek, edited by Charles W. private collectors. Of great importance, however, & A. Illinois Shabica Andrew Hay. Northeastern was his connection to private collectors. This 308 University, Chicago, Illinois, 1997: XVIII + pp., connection enabled him to view all new finds and 385 4 1 faunal $75.00 figs., tables, list; (hard cover) photograph them. His access to these collections ISBN 0-925065-21-8. was of importance to specialists because it provided with them material for a description of the diverse Since the last the Mazon Creek fauna. century, area around Richardson was able to motivate his col- in northern 100 km in Illinois, about southwest of leagues to engage themselves the Mazon Creek has been known for its Chicago, Pennsylvanian fossils, but he himself compiled mostly raw data fossils. Mainly plant fossils were found along and photographs. He could not finish the project, Mazon Creek and in the coal of that and Charles Shabica open pits area Dr. W. took over the com- until the 1950s. Langford (1958, 1963) was the pilation of the book after Richardson’s death in first to give a compilation of the flora and fauna 1983. Shabica enlisted 24 authors to write short of Mazon Creek. -

The Lower Permian Abo Formation in the Fra Cristobal and Caballo Mountains, Sierra County, New Mexico Spencer G

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/63 The Lower Permian Abo Formation in the Fra Cristobal and Caballo Mountains, Sierra County, New Mexico Spencer G. Lucas, Karl Krainer, Dan S. Chaney, William A. DiMichele, Sebastian Voigt, David S. Berman, and Amy C. Henrici, 2012, pp. 345-376 in: Geology of the Warm Springs Region, Lucas, Spencer G.; McLemore, Virginia T.; Lueth, Virgil W.; Spielmann, Justin A.; Krainer, Karl, New Mexico Geological Society 63rd Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 580 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 2012 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. -

Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha)

Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha) by Richard Kissel A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy Graduate Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology University of Toronto © Copyright by Richard Kissel 2010 Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha) Richard Kissel Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology University of Toronto 2010 Abstract Based on dental, cranial, and postcranial anatomy, members of the Permo-Carboniferous clade Diadectidae are generally regarded as the earliest tetrapods capable of processing high-fiber plant material; presented here is a review of diadectid morphology, phylogeny, taxonomy, and paleozoogeography. Phylogenetic analyses support the monophyly of Diadectidae within Diadectomorpha, the sister-group to Amniota, with Limnoscelis as the sister-taxon to Tseajaia + Diadectidae. Analysis of diadectid interrelationships of all known taxa for which adequate specimens and information are known—the first of its kind conducted—positions Ambedus pusillus as the sister-taxon to all other forms, with Diadectes sanmiguelensis, Orobates pabsti, Desmatodon hesperis, Diadectes absitus, and (Diadectes sideropelicus + Diadectes tenuitectes + Diasparactus zenos) representing progressively more derived taxa in a series of nested clades. In light of these results, it is recommended herein that the species Diadectes sanmiguelensis be referred to the new genus -

Early Tetrapod Relationships Revisited

Biol. Rev. (2003), 78, pp. 251–345. f Cambridge Philosophical Society 251 DOI: 10.1017/S1464793102006103 Printed in the United Kingdom Early tetrapod relationships revisited MARCELLO RUTA1*, MICHAEL I. COATES1 and DONALD L. J. QUICKE2 1 The Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy, The University of Chicago, 1027 East 57th Street, Chicago, IL 60637-1508, USA ([email protected]; [email protected]) 2 Department of Biology, Imperial College at Silwood Park, Ascot, Berkshire SL57PY, UK and Department of Entomology, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW75BD, UK ([email protected]) (Received 29 November 2001; revised 28 August 2002; accepted 2 September 2002) ABSTRACT In an attempt to investigate differences between the most widely discussed hypotheses of early tetrapod relation- ships, we assembled a new data matrix including 90 taxa coded for 319 cranial and postcranial characters. We have incorporated, where possible, original observations of numerous taxa spread throughout the major tetrapod clades. A stem-based (total-group) definition of Tetrapoda is preferred over apomorphy- and node-based (crown-group) definitions. This definition is operational, since it is based on a formal character analysis. A PAUP* search using a recently implemented version of the parsimony ratchet method yields 64 shortest trees. Differ- ences between these trees concern: (1) the internal relationships of aı¨stopods, the three selected species of which form a trichotomy; (2) the internal relationships of embolomeres, with Archeria -

A Juvenile Skeleton of the Nectridean Amphibian

Lucas, S.G. and Zeigler, K.E., eds., 2005, The Nonmarine Permian, New Mexico Museum of Natural Histoiy and Science Bulletin No. 30. 39 A JUVENILE SKELETON OF THE NECTRIDEAN AMPHIBIAN DIPLOCAULUS AND ASSOCIATED FLORA AND FAUNA FROM THE MITCHELL CREEK FLATS LOCALITY (UPPER WAGGONER RANCH FORMATION; EARLY PERMIAN), BAYLOR COUNTY, NORTH- CENTRAL TEXAS, USA DAN S. CHANEY, HANS-DIETER SUES AND WILLIAM A. DIMICHELE Department of Paleobiology MRC-121, National Museum of Natural History, PC Box 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013-7021 Abstract—A well-preserved skeleton of a tiny individual of the nectridean amphibian Diplocaulus was found in association with other Early Permian animal remains and a flora in a gray mudstone at a site called Mitchell Creek Flats in Baylor County, north-central Texas. The locality has the sedimentological attributes of a pond deposit. The skeleton of Diplocaulus sp. is noteworthy for its completeness and small size, and appears to represent a juvenile individual. The associated plant material is beautifully preserved and comprises the sphe- nopsids Annularia and Calamites, the conifer IBrachyphyllum, possible cycads represented by one or possibly two forms of Taeniopteris, three gigantopterids - Delnortea, Cathaysiopteris, and Gigantopteridium — and three unidentified callipterids. Several unidentified narrow trunks were found at the base of the deposit, appar- ently washed up against the northern margin of the pond. Other faunal material from the deposit comprises myalinid bivalves, conchostracans, a tooth of a xenacanthid shark, and a palaeonisciform fish. INTRODUCTION Wchita Rver T ^ Coinage i ^ 1 t Complete skeletons of Early Permian vertebrates are rare in north- FwmatJon Grcyp c central Texas, where much collecting has been done for about 150 years c c (Fig. -

Origin and Phylogenetic Relationships of Living Amphibians

Points of View Syst. Biol. 51(2):364–369, 2002 Tetrapod Phylogeny, Amphibian Origins, and the Denition of the Name Tetrapoda MICHEL LAURIN Equip´ e “Formations squelettiques” UMR CNRS 8570, Case 7077, Universite´ Paris 7, 75005 Paris, France; E-mail: [email protected] The most detailed, computer-generated Ahlberg and Milner, 1994) or did not include phylogeny of early amphibians has been amphibians (Gauthier et al., 1988), thus published recently (Anderson, 2001). The precluding identication of the dichotomy study was based on an analysis of 182 os- between amphibians and reptiliomorphs teological characters and 49 taxa, including (the clade that includes amniotes and the 41 “lepospondyls,” 7 other Paleozoic taxa extinct taxa that are more closely related representing other major groups (seymouri- to amniotes than to lissamphibians). The amorphs, embolomeres, temnospondyls, latest phylogeny (Anderson, 2001) suggests Downloaded By: [University of Tennessee] At: 00:39 18 January 2008 etc.), and a single lissamphibian (the oldest that despite initial skepticism (Coates et al., known apodan, the Jurassic taxon Eocae- 2000), the new pattern of stegocephalian cilia). The publication of this phylogeny is relationships appears to be well supported welcome, but several points raised in that and relatively stable, at least as it pertains to paper deserve to be discussed further. Espe- the relationships between major taxa such cially problematic are the views Anderson as Temnospondyli, Embolomeri, Seymouri- expressed about the polyphyletic origin of amorpha, Amniota, and the paraphyletic extant amphibians and about the application group informally called lepospondyls of phylogenetic nomenclature. (Figs. 1a, 1b). TETRAPOD PHYLOGENY Anderson (2001) found that the lep- Origin of Extant Amphibians ospondyls are more closely related to This brings us to the more difcult ques- amniotes than to seymouriamorphs and em- tion of amphibian origins. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE AMY C. HENRICI Collection Manager Section of Vertebrate Paleontology Carnegie Museum of Natural History 4400 Forbes Avenue Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213-4080, USA Phone:(412)622-1915 Email: [email protected] BACKGROUND Birthdate: 24 September 1957. Birthplace: Pittsburgh. Citizenship: USA. EDUCATION B.A. 1979, Hiram College, Ohio (Biology) M.S. 1989, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (Geology) CAREER Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) Laboratory Technician, Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1979 Research Assistant, Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1980 Curatorial Assistant, Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1980-1984 Scientific Preparator, Section of Paleobotany, 1985-1986 Scientific Preparator, Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1985-2002 Acting Collection Manager/Scientific Preparator, 2003-2004 Collection Manager, 2005-present PALEONTOLOGICAL FIELD EXPERIENCE Late Pennsylvanian through Early Permian of Colorado, New Mexico and Utah (fish, amphibians and reptiles) Early Permian of Germany, Bromacker quarry (amphibians and reptiles) Triassic of New Mexico, Coelophysis quarry (Coelophysis and other reptiles) Upper Jurassic of Colorado (mammals and herps) Tertiary of Montana, Nevada, and Wyoming (mammals and herps) Pleistocene of West Virginia (mammals and herps) Lake sediment cores and lake sediment surface samples, Wyoming (pollen and seeds) PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS Associate Editor, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1998-2000. Research Associate in the Science Division, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, 2007-present. PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATIONS Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paleontological Society LECTURES and TUTORIALS (Invited and public) 1994. Middle Eocene frogs from central Wyoming: ontogeny and taphonomy. California State University, San Bernardino 1994. Mechanical preparation of vertebrate fossils. California State University, San Bernardino 1994. Mechanical preparation of vertebrate fossils. University of Chicago 2001. -

Physical and Environmental Drivers of Paleozoic Tetrapod Dispersal Across Pangaea

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07623-x OPEN Physical and environmental drivers of Paleozoic tetrapod dispersal across Pangaea Neil Brocklehurst1,2, Emma M. Dunne3, Daniel D. Cashmore3 &Jӧrg Frӧbisch2,4 The Carboniferous and Permian were crucial intervals in the establishment of terrestrial ecosystems, which occurred alongside substantial environmental and climate changes throughout the globe, as well as the final assembly of the supercontinent of Pangaea. The fl 1234567890():,; in uence of these changes on tetrapod biogeography is highly contentious, with some authors suggesting a cosmopolitan fauna resulting from a lack of barriers, and some iden- tifying provincialism. Here we carry out a detailed historical biogeographic analysis of late Paleozoic tetrapods to study the patterns of dispersal and vicariance. A likelihood-based approach to infer ancestral areas is combined with stochastic mapping to assess rates of vicariance and dispersal. Both the late Carboniferous and the end-Guadalupian are char- acterised by a decrease in dispersal and a vicariance peak in amniotes and amphibians. The first of these shifts is attributed to orogenic activity, the second to increasing climate heterogeneity. 1 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3AN, UK. 2 Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz-Institut für Evolutions- und Biodiversitätsforschung, Invalidenstraße 43, 10115 Berlin, Germany. 3 School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK. 4 Institut -

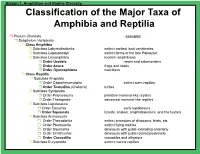

Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia

Station 1. Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia ! Phylum Chordata examples ! Subphylum Vertebrata ! Class Amphibia ! Subclass Labyrinthodontia extinct earliest land vertebrates ! Subclass Lepospondyli extinct forms of the late Paleozoic ! Subclass Lissamphibia modern amphibians ! Order Urodela newts and salamanders ! Order Anura frogs and toads ! Order Gymnophiona caecilians ! Class Reptilia ! Subclass Anapsida ! Order Captorhinomorpha extinct stem reptiles ! Order Testudina (Chelonia) turtles ! Subclass Synapsida ! Order Pelycosauria primitive mammal-like reptiles ! Order Therapsida advanced mammal-like reptiles ! Subclass Lepidosaura ! Order Eosuchia early lepidosaurs ! Order Squamata lizards, snakes, amphisbaenians, and the tuatara ! Subclass Archosauria ! Order Thecodontia extinct ancestors of dinosaurs, birds, etc ! Order Pterosauria extinct flying reptiles ! Order Saurischia dinosaurs with pubis extending anteriorly ! Order Ornithischia dinosaurs with pubis rotated posteriorly ! Order Crocodilia crocodiles and alligators ! Subclass Euryapsida extinct marine reptiles Station 1. Amphibian Skin AMPHIBIAN SKIN Most amphibians (amphi = double, bios = life) have a complex life history that often includes aquatic and terrestrial forms. All amphibians have bare skin - lacking scales, feathers, or hair -that is used for exchange of water, ions and gases. Both water and gases pass readily through amphibian skin. Cutaneous respiration depends on moisture, so most frogs and salamanders are -

Early Tetrapod Evolution: Red Queen Or Court Jester?

Early tetrapod evolution: Red Queen or Court Jester? Supervisors: Prof Mike Benton (School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol) – Main supervisor Dr Marcello Ruta (School of Life Sciences, University of Lincoln) Dr Alex Dunhill (Department of Biology and Biochemistry, University of Bath) Host Institution: University of Bristol Project description: In a Red Queen world, intrinsic factors that regulate biodiversity include body size, breadth of physiological tolerance, or adaptability to hard times. In a Court Jester world, species diversity depends on fluctuations in climate, landscape, and food supply. In reality, of course, both aspects might prevail in different ways and at different times. Behind the colourful allegories is a very simple, and yet key, question: are major differences in clade biodiversity driven by innate characteristics such as key adaptations/ innovations or by the chances of external crises and opportunities? Early tetrapods provide an excellent case study to explore large-scale adaptive radiations and environmental crises. The project will start with an existing database on early tetrapods (Benton et al. 2013), develop and improve this, and then explore key events. The database currently comprises 1388 valid genera, of which 391 are classed as ‘Amphibia’ (namely stem-tetrapods, Temnospondyli, Lepospondyli, Reptiliomorpha, Lissamphibia) and 997 as Amniota. The focus of the research will be on key events, primarily clade origins and expansions (‘adaptive radiations’) and mass extinctions. The two primary questions are (a) do adaptive radiations differ from diversifications following mass extinctions, and (b) how much biodiversity at certain times can be attributed to intrinsic factors and how much to extrinsic? Benton, M.J., Ruta, M., Dunhill, A.M., and Sakamoto, M. -

Bones, Molecules, and Crown- Tetrapod Origins

TTEC11 05/06/2003 11:47 AM Page 224 Chapter 11 Bones, molecules, and crown- tetrapod origins Marcello Ruta and Michael I. Coates ABSTRACT The timing of major events in the evolutionary history of early tetrapods is discussed in the light of a new cladistic analysis. The phylogenetic implications of this are com- pared with those of the most widely discussed, recent hypotheses of basal tetrapod interrelationships. Regardless of the sequence of cladogenetic events and positions of various Early Carboniferous taxa, these fossil-based analyses imply that the tetrapod crown-group had originated by the mid- to late Viséan. However, such estimates of the lissamphibian–amniote divergence fall short of the date implied by molecular studies. Uneven rates of molecular substitutions might be held responsible for the mismatch between molecular and morphological approaches, but the patchy quality of the fossil record also plays an important role. Morphology-based estimates of evolutionary chronology are highly sensitive to new fossil discoveries, the interpreta- tion and dating of such material, and the impact on tree topologies. Furthermore, the earliest and most primitive taxa are almost always known from very few fossil localities, with the result that these are likely to exert a disproportionate influence. Fossils and molecules should be treated as complementary approaches, rather than as conflicting and irreconcilable methods. Introduction Modern tetrapods have a long evolutionary history dating back to the Late Devonian. Their origins are rooted into a diverse, paraphyletic assemblage of lobe-finned bony fishes known as the ‘osteolepiforms’ (Cloutier and Ahlberg 1996; Janvier 1996; Ahlberg and Johanson 1998; Jeffery 2001; Johanson and Ahlberg 2001; Zhu and Schultze 2001). -

1 1 Appendix S1: Complete List of Characters And

1 1 Appendix S1: Complete list of characters and modifications to the data matrix of RC07, with 2 reports of new observations of specimens. 3 The names, the abbreviations and the order of all characters and their states are 4 unchanged from RC07 unless a change is explained. We renumbered the characters we did 5 not delete from 1 to 277, so the character numbers do not match those of RC07. However, 6 merged characters retain the abbreviations of all their components: PREMAX 1-2-3 (our 7 character 1) consists of the characters PREMAX 1, PREMAX 2 and PREMAX 3 of RC07, 8 while MAX 5/PAL 5 (our ch. 22) is assembled from MAX 5 and PAL 5 of RC07. We did not 9 add any characters, except for splitting state 1 of INT FEN 1 into the new state 1 of INT FEN 10 1 (ch. 84) and states 1 and 2 of the new character MED ROS 1 (ch. 85), undoing the merger 11 of PIN FOR 1 and PIN FOR 2 (ch. 91 and 92) and splitting state 0 of TEETH 3 into the new 12 state 0 of TEETH 3 (ch. 183) and the entire new character TEETH 10 (ch. 190). A few 13 characters have additional states or are recoded in other ways. Deleted characters are retained 14 here, together with the reasons why we deleted them and the changes we made to their scores. 15 All multistate characters mention in their names whether they are ordered, unordered, 16 or treated according to a stepmatrix.