Rachel Ley, Lady Llanover and the Triple Harp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Llangattock Court Penpergwm • Abergavenny • Monmouthshire Llangattock Court Penpergwm • Aberga Venny Monmouthshire • NP7 9AR

Llangattock Court PENPERGWM • ABERGAVENNY • MONMOUTHSHIRE Llangattock Court PenPergwm • AbergA venny monmouthshire • nP7 9Ar Splendidly situated period house and cottage Hall • Sitting room • Dining room • Drawing room Kitchen • Utility rooms • 6 Bedrooms 2 Bathrooms en suite • 2 Showers (1 en suite) Study • Storerooms • Cellars Llangattock Cottage with Sitting room • Dining room Kitchen/Breakfast room • 2 Bedrooms • Bathroom Garaging • Outbuildings • Gardens In all about 1.6 acres Abergavenny 3 miles • raglan 6 miles monmouth 12 miles (All distances are approximate) These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Situation Llangattock Court is in the small hamlet of Penpergwm which lies within the Usk Valley a few miles to the south east of Abergavenny. Abergavenny has all the expected shops and amenities of an important market town including a well appointed Waitrose. Monmouth has the excellent Haberdashers schools. Closer by is a local store/post office in the Bryn, the famous Hardwick restaurant, and a thriving tennis club. The A40 provides fast access to the M50/M5, and the M4 and the national motorway network and the A465 Heads of the Valley makes the major centres in South Wales highly accessible. Abergavenny has a rail station with a quick link to Newport and from there on to London Paddington (2 hours). Abergavenny is known as the gateway to the Brecon Beacons and the Black Mountains. There are leisure centres, parks and a castle; the Brecon Beacons are close-by; numerous local golf courses include Abergavenny, Monmouth (Rolls) and Newport (Celtic Manor), the Brecon and Monmouthshire Canal flows nearby; and there are numerous walks and rides through the surrounding countryside. -

Wyedene, St Arvans

WYEDENE, ST ARVANS Local Independent Professional Wyedene, St Arvans, Chepstow, Monmouthshire NP16 6EZ AN ARCHITECT DESIGNED 5 BEDROOM DETACHED HOUSE, CONSTRUCTED TO A HIGH SPECIFICATION, IN THE SOUGHT-AFTER VILLAGE OF ST ARVANS •Reception Hall •Sitting Room •Dining Room •Study •Kitchen/Breakfast Room •Utility Room •Cloakroom •5 Bedrooms •3 En-Suites •Family Bathroom •Garage/Workshop •Off-Road Parking •Gardens •Underfloor Heating to Ground Floor •Hardwood Oak Doors •Cat 5 Wiring •Sought-after Village Location •Walking distance of village facilities Location: – St Arvans is an extremely popular village at the approach to the Wye Valley, being some 2.5 miles from the M48 motorway, which gives access eastbound over the Severn Bridge to the M4, M32 and M5 intersection, and westbound to Newport, Cardiff and South Wales. Chepstow town offers modern shopping facilities, primary and senior schools, regular bus & train services and leisure & health centres. Locally, the village offers a public house and restaurant, place of worship, shop and a garage. The Wye valley with its numerous country walks is ‘on the doorstep’ as well as the forestry commissioned own Chepstow Park. The Property:- An individually designed detached residence, built to exacting standards providing spacious family accommodation. Of conventional build with part rendered and part stone elevations under a slate roof. The ground floor is covered with a cut stone tiled floor, whilst the first floor, apart from the bathrooms has engineered oak flooring. The ground floor is warmed via individually zoned under flooring, oil fired heating, New Build – Architect Certificate – Built to High Specification – Internal Viewing Highly Recommended £550,000 Portwall House, Bank Street, Chepstow, Monmouthshire, NP16 5EL Tel: 01291 626775 www.newlandrennie.com Email: [email protected] The accommodation comprises, all dimensions approximate:- Cloakroom: Automatic lighting, low level w.c, marble wash Utility Room: Plumbing for washing machine. -

68736 Caerwent Monmouthshire.Pdf

Wessex Archaeology Caerwent Roman Town, Monmouthshire, South Wales Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Ref:68736.01 February 2009 Caerwent Roman Town, Monmouthshire, South Wales Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared on behalf of: Videotext Communications Ltd 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON SW1 8QP By: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 68736.01 February 2009 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2009, all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Caerwent Roman Town, Monmouthshire, South Wales Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Contents Summary Acknowledgements 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................1 1.1 Project Background .................................................................................1 1.2 Archaeological Background....................................................................1 1.3 Previous Archaeological Work................................................................3 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ...................................................................................4 3 METHODS...........................................................................................................4 3.1 Topographical survey ..............................................................................4 3.2 Geophysical survey..................................................................................4 3.3 Evaluation -

The M4 Motorway (Rogiet Toll Plaza, Monmouthshire) (50 Mph Speed Limit) Regulations 2010 (Revocation) Regulations 2019

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. WELSH STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2019 No. 1306 (W. 227) ROAD TRAFFIC, WALES The M4 Motorway (Rogiet Toll Plaza, Monmouthshire) (50 mph Speed Limit) Regulations 2010 (Revocation) Regulations 2019 Made - - - - 3 October 2019 Laid before the National Assembly for Wales - - 7 October 2019 Coming into force - - 31 October 2019 The Welsh Ministers, in exercise of the powers conferred on them by section 17(2), (3) and (3ZAA) of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984(1), and after consultation with such representative organisations as were thought fit in accordance with section 134(10) of that Act, make the following Regulations. Title and commencement 1. The title of these Regulations is the M4 Motorway (Rogiet Toll Plaza, Monmouthshire) (50 mph Speed Limit) Regulations 2010 (Revocation) Regulations 2019 and they come into force on 31 October 2019. Revocation 2. The M4 Motorway (Rogiet Toll Plaza, Monmouthshire) (50 mph Speed Limit) Regulations 2010(2) are revoked. Ken Skates Minister for Economy and Transport, one of the 3 October 2019 Welsh Ministers (1) 1984 c. 27. Section 17(2) was amended by the New Roads and Street Works Act 1991 (c. 22), Schedule 8, paragraph 28(3) and the Road Traffic Act 1991 (c. 40), Schedule 4, paragraph 25 and Schedule 8. Section 17(3ZAA) was inserted by the Wales Act 2017 (c. 4), section 26(2). (2) S.I. 2010/1512 (W. 138). Document Generated: 2019-11-01 Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). -

BROOK COTTAGE Llanvetherine | Abergavenny | Monmouthshire | NP7 8RG

BROOK COTTAGE Llanvetherine | Abergavenny | Monmouthshire | NP7 8RG Brook Cottage • Country cottage sitting in pretty gardens • Three double bedrooms with lovely views • Well-proportioned reception rooms • Idyllic location adjoining open countryside • EPC Rating - D Located in the quiet village of Llanvetherine at the end of a private lane is this charming 19th century cottage with surrounding pleasant gardens. The detached character property is accessed through the front entrance door with storm porch over, directly into to a very welcoming living room with painted beams and woodburning stove sitting in a stone fireplace with wooden mantel. A door leads through to a spacious, open-plan dining room/kitchen with plenty of space for a large dining table and chairs and entrance door to the rear. The kitchen is fitted with a mixture of oak and painted base and wall units and includes a built-in electric oven with halogen hob and extractor over. The focal point is a cream oil-fired Rangemaster stove with a red brick surround and deep oak shelf above. At the end of the cottage is a utility room with space and plumbing for white goods, a useful storage cupboard and shower room with W.C. Off the kitchen is the conservatory with triple aspect windows offering splendid views across the gardens and surrounding countryside. From the living room, stairs rise to the first floor landing with windows overlooking the gardens and doors to the comfortable bedrooms. The principal bedroom is large, yet cosy with painted panelled ceiling and dual aspect windows. Along the landing are t wo fur ther double bedrooms and a family bathroom with airing cupboard and shower over the bath. -

Download the Programme for the Xvith International Congress of Celtic Studies

Logo a chynllun y clawr Cynlluniwyd logo’r XVIeg Gyngres gan Tom Pollock, ac mae’n seiliedig ar Frigwrn Capel Garmon (tua 50CC-OC50) a ddarganfuwyd ym 1852 ger fferm Carreg Goedog, Capel Garmon, ger Llanrwst, Conwy. Ceir rhagor o wybodaeth ar wefan Sain Ffagan Amgueddfa Werin Cymru: https://amgueddfa.cymru/oes_haearn_athrawon/gwrthrychau/brigwrn_capel_garmon/?_ga=2.228244894.201309 1070.1562827471-35887991.1562827471 Cynlluniwyd y clawr gan Meilyr Lynch ar sail delweddau o Lawysgrif Bangor 1 (Archifau a Chasgliadau Arbennig Prifysgol Bangor) a luniwyd yn y cyfnod 1425−75. Mae’r testun yn nelwedd y clawr blaen yn cynnwys rhan agoriadol Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, cyfieithiad Cymraeg o De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum, gan Hu Sant (Hugo o St. Victor). Rhan o ramadeg barddol a geir ar y clawr ôl. Logo and cover design The XVIth Congress logo was designed by Tom Pollock and is based on the Capel Garmon Firedog (c. 50BC-AD50) which was discovered in 1852 near Carreg Goedog farm, Capel Garmon, near Llanrwst, Conwy. Further information will be found on the St Fagans National Museum of History wesite: https://museum.wales/iron_age_teachers/artefacts/capel_garmon_firedog/?_ga=2.228244894.2013091070.156282 7471-35887991.1562827471 The cover design, by Meilyr Lynch, is based on images from Bangor 1 Manuscript (Bangor University Archives and Special Collections) which was copied 1425−75. The text on the front cover is the opening part of Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, a Welsh translation of De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum (Hugo of St. Victor). The back-cover text comes from the Bangor 1 bardic grammar. -

MONMOUTHSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL Housing Support Grant (Supporting People, Homelessness Prevention & Rent Smart Wales)

MONMOUTHSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL Housing Support Grant (Supporting People, Homelessness Prevention & Rent Smart Wales) SERVICES DIRECTORY 1 CONTENTS PAGE What is Housing Support Grant? 3 What is Housing Related Support? 3 Who can access Housing Support Services? 4 How to access the Housing Support Services 5 Domestic Abuse services 7 Mental Health Services 9 Young People Services 10 Family Support Services 11 Older People Services 12 Generic Services 12 Regional Services 14 Housing Support Grant Contacts 15 2 What is Housing Support Grant? Housing Support Grant core purpose is to prevent homelessness and support people to have the capability, independence, skills and confidence to access and/or maintain a stable and suitable home. Housing is a key priority area in the Welsh Government’s Prosperity for All National Strategy, which sets out the vision that “We want everyone to live in a home that meets their needs and supports a healthy, successful and prosperous life”. What is Housing Related Support? Monmouthshire County Council Housing Support Grant supports the aim of working together to prevent homelessness and where it cannot be prevented, ensuring it is rare, brief and un-repeated. To do this we need to tackle the root cause of homelessness and work to enable people to stay in their own homes longer. Housing related support seeks to enable vulnerable people to maintain and increase their independence and capacity to remain in their own home. These are some examples of housing related support: . Advice with budgeting/managing your money. Helping to get advice on benefits and grants. Support with social inclusion. -

Monmouthshire County Council

Review of Asset Management – Monmouthshire County Council Audit year: 2016-17 Date issued: November 2017 Document reference: 186A2017-18 This document has been prepared as part of work performed in accordance with statutory functions. In the event of receiving a request for information to which this document may be relevant, attention is drawn to the Code of Practice issued under section 45 of the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The section 45 code sets out the practice in the handling of requests that is expected of public authorities, including consultation with relevant third parties. In relation to this document, the Auditor General for Wales and the Wales Audit Office are relevant third parties. Any enquiries regarding disclosure or re-use of this document should be sent to the Wales Audit Office at [email protected]. The team who delivered the work comprised Steve Frank, Allison Rees, Dave Wilson, programme managed by Non Jenkins under the direction of Huw Rees. Page 2 of 12 - Review of Asset Management – Monmouthshire County Council Contents Summary report The Council has a good understanding of its assets, however it lacks a strategic approach and effective information technology to support the management of its assets 4 Proposals for improvement 5 Detailed report The Council has an Asset Management Plan but this is not time bound and focuses on the short term 6 The Council can show improved use of some assets but asset management arrangements are not well co-ordinated or supported by effective IT systems 8 The Council reviews its ongoing use of assets but the Asset Management Plan remains unchanged since 2014 10 Page 3 of 12 - Review of Asset Management – Monmouthshire County Council Summary report The Council has a good understanding of its assets, however, it lacks a strategic approach and effective information technology to support the management of assets 1 Asset management seeks to align the asset portfolio with the needs of the organisation. -

Download Booklet

Heavenly Harp BEST LOVED classical harp music Heavenly Harp Best loved classical harp music 1 Alphonse HASSELMANS (1845–1912) 10 Henriette RENIÉ (1875–1956) La Source, Op. 44 3:55 Danse des Lutins 3:59 Erica Goodman (8.573947) Judy Loman (8.554347) 2 Hugo REINHOLD (1854–1935) 11 Marcel TOURNIER (1879–1951) Impromptu in C sharp minor, Op. 28, No. 3 5:35 Vers la source dans le bois 4:18 Elizabeth Hainen (8.555791) (‘Towards the Fountain in the Wood’) Judy Loman (8.554561) 3 John THOMAS (1826–1913) Dyddiau Mebyd (‘Scenes of Childhood’) – 3:05 12 Gabriel FAURÉ (1845–1924) II. Toriad y Dydd (‘The Dawn of Day’) Une chatelaine en sa tour, Op. 110 4:41 Lipman Harp Duo (8.570372) Judy Loman (8.554561) 4 Gaetano DONIZETTI (1797–1848) 13 Elias PARISH ALVARS (1808–1849) Lucia di Lammermoor, Act 1 Scene 2 4:25 Serenade, Op. 83 – Serenade 7:13 (arr. A.H. Zabel) Elizabeth Hainen (8.555791) Elizabeth Hainen (8.555791) 14 Gabriel PIERNÉ (1863–1937) 5 Marcel GRANDJANY (1891–1975) Impromptu-caprice, Op. 9 5:51 Fantasy on a Theme of Haydn, Op. 31 7:54 Ellen Bødtker (8.555328) Judy Loman (8.554561) 15 Nino ROTA (1911–1979) 6 Manuel de FALLA (1876–1946) Toccata 2:33 La vida breve, Act II – 4:11 Elisa Netzer (8.573835) Danse espagnole No. 1 (ver. For 2 guitars) Judy Loman (8.554561) 16 John PARRY (1710–1782) Sonata No. 2 – Siciliana 2:06 7 Sophia DUSSEK (1775–1847) Judy Loman (8.554347) Sonata – Allegro 2:39 Judy Loman (8.554347) 17 Carl Philipp Emanuel BACH (1714–1788) 12 Variations on La folia d’Espagne, 9:13 8 Louis SPOHR (1784–1859) Wq. -

108 CROESONEN PARC Abergavenny | Monmouthshire | NP7 6PF

108 CROESONEN PARC Abergavenny | Monmouthshire | NP7 6PF 01873 858990 108, Croesonen Parc Immaculately presented detached family home. • Five bedrooms and three generous reception rooms • Neutral décor throughout with ample natural lighting • Large enclosed rear garden with delightful conservatory • Off-road driveway parking and integrated garage • EPC Rating - D STEP INSIDE This immaculately presented five-bedroom detached house is situated in a cul-de-sac location adjoining open countr yside with views to the Skirrid and Blorenge Mountains. A welcoming part-glazed front door opens into a spacious entrance hall, decorated with neutral tones and wood finish flooring. The hall is equipped with two useful storage cupboards and provides access to the study, cloakroom with W.C. and principal rooms. Extending to over 27’, the large open-plan family room affords versatile space with a bay- fronted window which floods the room with natural light. The dining area has sliding doors into the conservatory with tiled floor and lovely views over the garden. An archway leads to the well-appointed kitchen, fitted with an extensive range of cupboards with integrated appliances, a built-in cooker with halogen hob and extractor over, a breakfast area and external door to the garden. Adjacent is a utility room with further storage, space and plumbing for appliances and access to the garage. Stairs rise from the hallway to a split landing providing access to two well-proportioned bedrooms to one side, and three further bedrooms to the other, two of which with built-in wardrobes. There is also a generous family bathroom with contemporary walk-in shower enclosure and feature window shutters. -

Stone House, Cupids Hill, Grosmont, Monmouthshire, NP7

Stone House, Cupids Hill, Grosmont, Monmouthshire, NP7 8ES £450,000 A spacious, detached 4 bedroom family house with beautiful countryside views with annexe potential, large gardens, ample parking, double glazing and oil heating. Sold with NO ONWARD CHAIN. Introduction Gardens and parking Energy Performance Graphs A spacious, detached house with lovely countryside The property enjoys far reaching countryside views to views comprising; entrance hallway, living room with the rear. The main garden is to the side of the open fire, kitchen/ breakfast room, dining room, sun property and is over two tiers; it is primarily laid to room, utility room, cloakroom, store room, 4 lawn and is enclosed by fencing. There is a large patio bedrooms, 1 ensuite shower room and family area and ample off road parking. bathroom. The property has oil heating, PVCu double Location glazing and has been newly decorated. Located in the village of Grosmont (10 miles Property description Monmouth, 11 miles Abergavenny, 14 miles Hereford, From a canopy entrance porch there is an entrance 15 miles Ross on Wye/ M50. Cardiff is approx 40 door into a hallway with parquet flooring, stairs to the minutes drive) Grosmont has many local amenities first floor and stairs down to the cellar. The living including Post Office, Tea Rooms, Public House/ room has an open fire and PVCu double glazed Restaurant, Church, Castle and is nestled in a lovely windows to three aspects overlooking the valley with many rural walks. Cross Ash is 3 miles surrounding countryside and a newly fitted carpet. away and has a primary school. -

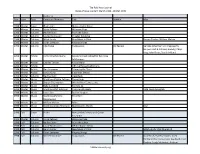

The Folk Harp Journal Index of Issue Content March 1986 - Winter 1998

The Folk Harp Journal Index of Issue Content March 1986 - Winter 1998 Author or Year Issue Type Composer/Arranger Title Subtitle Misc 1998 Winter Cover Illustration Make a Joyful Noise 1998 Winter Column Sylvia Fellows Welcome Page 1998 Winter Column Nadine Bunn From the Editor 1998 Winter Column Laurie Rasmussen Chapter Roundup 1998 Winter Column Mitch Landy New Music in Print Harper Tasche; William Mahan 1998 Winter Column Dinah LeHoven Ringing Strings 1998 Winter Column Alys Howe Harpsounds CD Review Verlene Schermer; Lori Pappajohn; Harpers Hall & Culinary Society; Chrys King; John Doan; David Helfand 1998 Winter Article Patty Anne McAdams Second annual retreat for Bay Area folk harpers 1998 Winter Article Charles Tanner A Cool Harp! 1998 Winter Article Fifth Gulf Coast Celtic harp 1998 Winter Article Ann Heymann Trimming the Tune 1998 Winter Article James Kurtz Electronic Effects 1998 Winter Column Nadine Bunn Classifieds 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Sylvia Fellows Three Kings 1998 Winter Music Sharon Thormahlen Where River Turns to sky 1998 Winter Music Reba Lunsford Tootie's Jig 1998 Winter Music Traditional/M. Schroyer The Friendly Beats 12th Century English 1998 Winter Music Joyce Rice By Yon Yangtze 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Serena He is Born Underwood 1998 Winter Music William Mahan Adios 1998 Winter Music Traditional/Ann Heymann MacDonald's March Irish 1998 Fall Cover Photo New Zealand's Harp and Guitar Ensemble 1998 Winter Column Sylvia Fellows Welcome Page 1998 Fall Column Nadine Bunn From the Editor 1998 Fall Column