Northwest Ethnobotany Field Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornaceae – Dogwood Family Cornus Florida Flowering Dogwood

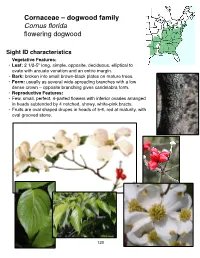

Cornaceae – dogwood family Cornus florida flowering dogwood Sight ID characteristics Vegetative Features: • Leaf: 2 1/2-5" long, simple, opposite, deciduous, elliptical to ovate with arcuate venation and an entire margin. • Bark: broken into small brown-black plates on mature trees. • Form: usually as several wide-spreading branches with a low dense crown – opposite branching gives candelabra form. • Reproductive Features: • Few, small, perfect, 4-parted flowers with inferior ovaries arranged in heads subtended by 4 notched, showy, white-pink bracts. • Fruits are oval shaped drupes in heads of 5-6, red at maturity, with oval grooved stone. 123 NOTES AND SKETCHES 124 Cornaceae – dogwood family Cornus nuttallii Pacific dogwood Sight ID characteristics Vegetative Features: • Leaf: 2 1/2-4 1/2" long, simple, opposite, deciduous, ovate- elliptical with arcuate venation, margin may be sparsely toothed or entire. • Bark: dark and broken into small plates at maturity. • Form: straight trunk and narrow crown in forested conditions, many-trunked and bushy in open. • Reproductive Features: • Many yellowish-green, small, perfect, 4-parted flowers with inferior ovaries arranged in dense in heads, subtended by 4-7 showy white- pink, petal-like bracts - not notched at the apex. • Fruits are drupes in heads of 30-40, red at maturity and they have smooth stones. 125 NOTES AND SKETCHES 126 Cornaceae – dogwood family Cornus sericea red-osier dogwood Sight ID characteristics Vegetative Features: • Leaf: 2-4" long, simple, opposite, deciduous and somewhat narrow ovate-lanceolate with entire margin. • Twig: bright red, sometimes green splotched with red, white pith. • Bark: red to green with numerous lenticels; later developing larger cracks and splits and turning light brown. -

A Black Huckleberry Case Study in the Kootenay Region of British Columbia

Extension Note HOBBY AND KEEFER BC Journal of Ecosystems and Management A black huckleberry case study in the Kootenay region of British Columbia Tom Hobby1 and Michael E. Keefer2 Abstract This case study explores the commercial development of black huckleberries (Vaccinium membranaceum Dougl.) in the Kootenay region of British Columbia. Black huckleberries have a long history of human and wildlife use, and there are increasing demands on the resource in the region. Conflicts between commercial, traditional, and recreational users have emerged over expanding the harvest of this non-timber forest product (NTFP). This case study explores the potential for expanding huckleberry commercialization by examining the potential management and policy options that would support a sustainable commercial harvest. The article also reviews trends and issues within the huckleberry sector and ecological research currently conducted within the region. keywords: British Columbia; forest ecology; forest economic development; forest management; huckleberries; non-timber forest products; wildlife. Contact Information 1 Consultant, SCR Management Inc., PO Box 341, Malahat, BC V0R 2L0. Email: [email protected] 2 Principal, Keefer Ecological Services Ltd., 3816 Highland Road, Cranbrook, BC V1C 6X7. Email: [email protected] Editor’s Note: Please refer to Mitchell and Hobby (2010; see page 27) in this special issue for a description of the overall non-timber forest product project and details of the methodology employed in the case studies. JEM — VOLU me 11, NU M B E RS 1 AND 2 Published by FORREX Forum for Research and Extension in Natural Resources Hobby,52 T. and M.E. Keefer. 2010. A blackJEM huckleberry — VOLU me case 11, study NU M inB E RSthe 1 Kootenay AND 2 region of British Columbia. -

Echinocystis Lobata Torr. Et A. Gray) – Literární Rešerše

JIHOČESKÁ UNIVERZITA V ČESKÝCH BUDĚJOVICÍCH ZEMĚDĚLSKÁ FAKULTA Studijní program: B4131 Zemědělství Studijní obor: Agroekologie Katedra: Katedra biologických disciplín Vedoucí katedry: doc. RNDr. Ing. Josef Rajchard, Ph.D. BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE Biologie štětince laločnatého (Echinocystis lobata Torr. et A. Gray) – literární rešerše Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Ing. Zuzana Balounová, Ph.D. Autor: Radka Kučerová České Budějovice, 2013 Prohlášení autora bakalářské práce Prohlašuji, že svoji bakalářskou práci jsem vypracovala samostatně pouze s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedených v seznamu citované literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. v platném znění souhlasím se zveřejněním své bakalářské práce a to v nezkrácené podobě (v úpravě vzniklé vypuštěním vyznačených částí archivovaných Zemědělskou fakultou JU) elektronickou cestou ve veřejně přístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jihočeskou univerzitou v Českých Budějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách. Datum ................... Podpis studenta .............................. Poděkování: Upřímně děkuji vedoucí bakalářské práce paní Ing. Zuzaně Balounové Ph.D., za odborné vedení a cenné rady, které mi udělovala při vypracování práce, také bych chtěla poděkovat za pomoc svému bývalému vedoucímu práce Ing. Vítu Jozovi. Mé díky patří také rodině a blízkým přátelům za to, že mě podporovali ve studiu na univerzitě. Souhrn Bakalářská práce pojednává o biologii štětince laločnatého (Echinocystis lobata Torr. et A. Gray). První kapitola je zaměřena na systematiku členění, dále se práce zabývá morfologií, rozšířením, stanovištními podmínkami, životním cyklem, vztahy s ostatními organismy a problematiku invaznosti. Invaznost je v současnosti aktuálním problémem, protože dochází k vytlačování původních druhů rostlin. Klíčová slova: Echinocystis lobata, štětinec laločnatý, invaze, Cucurbitaceae, biologie Abstract The thesis deals with biological flora of Wild Cucumber (Echinocystis lobata Torr. -

Songhees Pictorial

Songhees Pictorial A History ofthe Songhees People as seen by Outsiders, 1790 - 1912 by Grant Keddie Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria, 2003. 175pp., illus., maps, bib., index. $39.95. ISBN 0-7726-4964-2. I remember making an appointment with Dan Savard in or der to view the Sali sh division ofthe provincial museum's photo collections. After some security precautions, I was ushered into a vast room ofcabi nets in which were the ethnological photographs. One corner was the Salish division- fairly small compared with the larger room and yet what a goldmine of images. [ spent my day thumbing through pictures and writing down the numbers name Songhees appeared. Given the similarity of the sounds of of cool photos I wished to purchase. It didn't take too long to some of these names to Sami sh and Saanich, l would be more cau see that I could never personally afford even the numbers I had tious as to whom is being referred. The oldest journal reference written down at that point. [ was struck by the number of quite indicating tribal territory in this area is the Galiano expedi tion excellent photos in the collection, which had not been published (Wagner 1933). From June 5th to June 9th 1792, contact was to my knowledge. I compared this with the few photos that seem maintained with Tetacus, a Makah tyee who accompanied the to be published again and again. Well, Grant Keddie has had expedi tion to his "seed gathering" village at Esquimalt Harbour. access to this intriguing collection, with modern high-resolution At this time, Victoria may have been in Makah territory or at least scanning equipment, and has prepared this edited collecti on fo r high-ranking marriage alliances gave them access to the camus our v1ewmg. -

Likely to Have Habitat Within Iras That ALLOW Road

Item 3a - Sensitive Species National Master List By Region and Species Group Not likely to have habitat within IRAs Not likely to have Federal Likely to have habitat that DO NOT ALLOW habitat within IRAs Candidate within IRAs that DO Likely to have habitat road (re)construction that ALLOW road Forest Service Species Under NOT ALLOW road within IRAs that ALLOW but could be (re)construction but Species Scientific Name Common Name Species Group Region ESA (re)construction? road (re)construction? affected? could be affected? Bufo boreas boreas Boreal Western Toad Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Plethodon vandykei idahoensis Coeur D'Alene Salamander Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Rana pipiens Northern Leopard Frog Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Accipiter gentilis Northern Goshawk Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Ammodramus bairdii Baird's Sparrow Bird 1 No No Yes No No Anthus spragueii Sprague's Pipit Bird 1 No No Yes No No Centrocercus urophasianus Sage Grouse Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Falco peregrinus anatum American Peregrine Falcon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Gavia immer Common Loon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Lanius ludovicianus Loggerhead Shrike Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Oreortyx pictus Mountain Quail Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Otus flammeolus Flammulated Owl Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides albolarvatus White-Headed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides arcticus Black-Backed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Speotyto cunicularia Burrowing -

Tree of Life Marula Oil in Africa

HerbalGram 79 • August – October 2008 HerbalGram 79 • August Herbs and Thyroid Disease • Rosehips for Osteoarthritis • Pelargonium for Bronchitis • Herbs of the Painted Desert The Journal of the American Botanical Council Number 79 | August – October 2008 Herbs and Thyroid Disease • Rosehips for Osteoarthritis • Pelargonium for Bronchitis • Herbs of the Painted Desert • Herbs of the Painted Bronchitis for Osteoarthritis Disease • Rosehips for • Pelargonium Thyroid Herbs and www.herbalgram.org www.herbalgram.org US/CAN $6.95 Tree of Life Marula Oil in Africa www.herbalgram.org Herb Pharm’s Botanical Education Garden PRESERVING THE FULL-SPECTRUM OF NATURE'S CHEMISTRY The Art & Science of Herbal Extraction At Herb Pharm we continue to revere and follow the centuries-old, time- proven wisdom of traditional herbal medicine, but we integrate that wisdom with the herbal sciences and technology of the 21st Century. We produce our herbal extracts in our new, FDA-audited, GMP- compliant herb processing facility which is located just two miles from our certified-organic herb farm. This assures prompt delivery of freshly-harvested herbs directly from the fields, or recently HPLC chromatograph showing dried herbs directly from the farm’s drying loft. Here we also biochemical consistency of 6 receive other organic and wildcrafted herbs from various parts of batches of St. John’s Wort extracts the USA and world. In producing our herbal extracts we use precision scientific instru- ments to analyze each herb’s many chemical compounds. However, You’ll find Herb Pharm we do not focus entirely on the herb’s so-called “active compound(s)” at fine natural products and, instead, treat each herb and its chemical compounds as an integrated whole. -

Huckleberry Picking at Priest Lake

HUCKLEBERRY (Vaccinium Membranaceum) USDA Forest Service Other Common Names Northern Region Blueberry, Big Whortleberry, Black Idaho Panhandle Huckleberry, Bilberry. National Forests Description: The huckleberry is a low erect shrub, ranging from 1-5' tall. The flowers are shaped like tiny pink or white urns, which blossom in June and July, depending on elevation. The leaves are short, elliptical and alter- native on the stems. The bush turns brilliant red and sheds its leaves in the fall. The stem bark is reddish (often yellowish-green in shaded sites). The shape of the berry varies The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) from round to oval and the color var- prohibits discrimination in its programs on the basis ies from purplish black to wine- of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disa- colored red. Some species have a bility, political beliefs, and marital or familial status. dusky blue covering called bloom. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Per- The berries taste sweet and tart, in sons with disabilities who require alternative means the same proportions. of communication of program information (braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's Ripening Season: July-August TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). Early in the season, by mid-July, the berries on sunny southern facing To file a complaint, write the Secretary of Agriculture, Huckleberry slopes and lower elevations are first U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC to ripen. They are most succulent in 20250, or call 1-800-795-3272 (voice) or 202-720- mid-summer. However, good pick- 6382 (TDD). -

Flowering Plants Eudicots Apiales, Gentianales (Except Rubiaceae)

Edited by K. Kubitzki Volume XV Flowering Plants Eudicots Apiales, Gentianales (except Rubiaceae) Joachim W. Kadereit · Volker Bittrich (Eds.) THE FAMILIES AND GENERA OF VASCULAR PLANTS Edited by K. Kubitzki For further volumes see list at the end of the book and: http://www.springer.com/series/1306 The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants Edited by K. Kubitzki Flowering Plants Á Eudicots XV Apiales, Gentianales (except Rubiaceae) Volume Editors: Joachim W. Kadereit • Volker Bittrich With 85 Figures Editors Joachim W. Kadereit Volker Bittrich Johannes Gutenberg Campinas Universita¨t Mainz Brazil Mainz Germany Series Editor Prof. Dr. Klaus Kubitzki Universita¨t Hamburg Biozentrum Klein-Flottbek und Botanischer Garten 22609 Hamburg Germany The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants ISBN 978-3-319-93604-8 ISBN 978-3-319-93605-5 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93605-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018961008 # Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Vascular Plants at Fort Ross State Historic Park

19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450 ■ 707.847.3437 ■ [email protected] ■ www.fortross.org Title: Vascular Plants at Fort Ross State Historic Park Author(s): Dorothy Scherer Published by: California Native Plant Society i Source: Fort Ross Conservancy Library URL: www.fortross.org Fort Ross Conservancy (FRC) asks that you acknowledge FRC as the source of the content; if you use material from FRC online, we request that you link directly to the URL provided. If you use the content offline, we ask that you credit the source as follows: “Courtesy of Fort Ross Conservancy, www.fortross.org.” Fort Ross Conservancy, a 501(c)(3) and California State Park cooperating association, connects people to the history and beauty of Fort Ross and Salt Point State Parks. © Fort Ross Conservancy, 19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450, 707-847-3437 .~ ) VASCULAR PLANTS of FORT ROSS STATE HISTORIC PARK SONOMA COUNTY A PLANT COMMUNITIES PROJECT DOROTHY KING YOUNG CHAPTER CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY DOROTHY SCHERER, CHAIRPERSON DECEMBER 30, 1999 ) Vascular Plants of Fort Ross State Historic Park August 18, 2000 Family Botanical Name Common Name Plant Habitat Listed/ Community Comments Ferns & Fern Allies: Azollaceae/Mosquito Fern Azo/la filiculoides Mosquito Fern wp Blechnaceae/Deer Fern Blechnum spicant Deer Fern RV mp,sp Woodwardia fimbriata Giant Chain Fern RV wp Oennstaedtiaceae/Bracken Fern Pleridium aquilinum var. pubescens Bracken, Brake CG,CC,CF mh T Oryopteridaceae/Wood Fern Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosorum Western lady Fern RV sp,wp Dryopteris arguta Coastal Wood Fern OS op,st Dryopteris expansa Spreading Wood Fern RV sp,wp Polystichum munitum Western Sword Fern CF mh,mp Equisetaceae/Horsetail Equisetum arvense Common Horsetail RV ds,mp Equisetum hyemale ssp.affine Common Scouring Rush RV mp,sg Equisetum laevigatum Smooth Scouring Rush mp,sg Equisetum telmateia ssp. -

An Examination of Nuu-Chah-Nulth Culture History

SINCE KWATYAT LIVED ON EARTH: AN EXAMINATION OF NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURE HISTORY Alan D. McMillan B.A., University of Saskatchewan M.A., University of British Columbia THESIS SUBMI'ITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Alan D. McMillan SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Alan D. McMillan Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis Since Kwatyat Lived on Earth: An Examination of Nuu-chah-nulth Culture History Examining Committe: Chair: J. Nance Roy L. Carlson Senior Supervisor Philip M. Hobler David V. Burley Internal External Examiner Madonna L. Moss Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon External Examiner Date Approved: krb,,,) 1s lwb PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

The Mycological Society of San Francisco • Jan. 2016, Vol. 67:05

The Mycological Society of San Francisco • Jan. 2016, vol. 67:05 Table of Contents JANUARY 19 General Meeting Speaker Mushroom of the Month by K. Litchfield 1 President Post by B. Wenck-Reilly 2 Robert Dale Rogers Schizophyllum by D. Arora & W. So 4 Culinary Corner by H. Lunan 5 Hospitality by E. Multhaup 5 Holiday Dinner 2015 Report by E. Multhaup 6 Bizarre World of Fungi: 1965 by B. Sommer 7 Academic Quadrant by J. Shay 8 Announcements / Events 9 2015 Fungus Fair by J. Shay 10 David Arora’s talk by D. Tighe 11 Cultivation Quarters by K. Litchfield 12 Fungus Fair Species list by D. Nolan 13 Calendar 15 Mushroom of the Month: Chanterelle by Ken Litchfield Twenty-One Myths of Medicinal Mushrooms: Information on the use of medicinal mushrooms for This month’s profiled mushroom is the delectable Chan- preventive and therapeutic modalities has increased terelle, one of the most distinctive and easily recognized mush- on the internet in the past decade. Some is based on rooms in all its many colors and meaty forms. These golden, yellow, science and most on marketing. This talk will look white, rosy, scarlet, purple, blue, and black cornucopias of succu- at 21 common misconceptions, helping separate fact lent brawn belong to the genera Cantharellus, Craterellus, Gomphus, from fiction. Turbinellus, and Polyozellus. Rather than popping up quickly from quiescent primordial buttons that only need enough rain to expand About the speaker: the preformed babies, Robert Dale Rogers has been an herbalist for over forty these mushrooms re- years. He has a Bachelor of Science from the Univer- quire an extended period sity of Alberta, where he is an assistant clinical profes- of slower growth and sor in Family Medicine. -

April 11, 2010 Black Diamond Regional Park, 114 Species, 51 Families Dean G Kelch & Richard Beidleman

April 11, 2010 Black Diamond Regional Park, 114 species, 51 families Dean G Kelch & Richard Beidleman Anacardiaceae Schinus (Greek) molle (soft) Peruvian Peppertree L. Anacardiaceae Toxicodendron (toxic tree) diversilobum (diverse lobes) Western Poison- oak Greene Apiaceae Lomatium (bordered) utriculatum (with bladders) Spring-gold (Torrey&Gray) Coulter & Rose Apiaceae Sanicula (to heal) bipinnata (forked) Poison Sanicle Hooker&Arnott Apiaceae Sanicula bipinnatifida (forked) Purple Sanicle Hooker Apiaceae Sanicula tuberosa (with a tube) Tuberous Sanicle Torrey Asteraceae Achillea (Achilles) millefolium (thousand leaved) Yarrow Linneaus Asteraceae Artemisia (Artemis) californica California Sage brush Lessing Asteraceae Agoseris (goat chicory) heterophylla (variable leaf) Annual Dandelion (Nuttall) Greene Asteraceae Baccharis (Bacchus) pilularis (hairy) Coyotebrush de Candolle Asteraceae Balsamorhiza(balsamroot) macrolepis (large scale) Bigscale Balsamroot W. Sharp Asteraceae Centaurea (Greek) solstitialis (midsummer) Yellow Star-thistle L. Asteraceae Gnaphalium (lock of wool) californicum California Everlasting de Candolle Asteraceae Grindelia (D.H. Grindel 1776-1836 Latvian Bot.) camporum (country) Great Valley Gumplant Greene Asteraceae Helianthella (little sunflower) castanea (chestnut) Mt. Diablo sunflower Greene Asteraceae Lactuca (milky) virosa (fetid) Wild Lettuce L Asteraceae Micropus (small foot) amphibolus Mount Diablo cottonweed A. Gray Asteraceae Micropus californicus Slender Cottonwood Fischer & C. Meyer Asteraceae Santolina