Foreign News: Where Is Signor X?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aiello Calabro (CS) Italy

Dr. Francesco Gallo OUTSTANDING FAMILIES of Aiello Calabro (CS) Italy from the XVI to the XX centuries EMIGRATION to USA and Canada from 1880 to 1930 Padua, Italy August 2014 1 Photo on front cover: Graphic drawing of Aiello of the XVII century by Pietro Angius 2014, an readaptation of Giovan Battista Pacichelli's drawing of 1693 (see page 6) Photo on page 1: Oil painting of Aiello Calabro by Rosario Bernardo (1993) Photo on back cover: George Benjamin Luks, In the Steerage, 1900 Oil on canvas 77.8 x 48.9 cm North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh. Purchased with funds from the Elizabeth Gibson Taylor and Walter Frank Taylor Fund and the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. Phifer Bequest), 98.12 2 With deep felt gratitude and humility I dedicate this publication to Prof. Rocco Liberti a pioneer in studying Aiello's local history and author of the books: "Ajello Calabro: note storiche " published in 1969 and "Storia dello Stato di Aiello in Calabria " published in 1978 The author is Francesco Gallo, a Medical Doctor, a Psychiatrist, a Professor at the University of Maryland (European Division) and a local history researcher. He is a member of various historical societies: Historical Association of Calabria, Academy of Cosenza and Historic Salida Inc. 3 Coat of arms of some Aiellese noble families (from the book by Cesare Orlandi (1734-1779): "Delle città d'Italia e sue isole adjacenti compendiose notizie", Printer "Augusta" in Perugia, 1770) 4 SUMMARY of the book Introduction 7 Presentation 9 Brief History of the town of Aiello Calabro -

Chapter One: Introduction

CHANGING PERCEPTIONS OF IL DUCE TRACING POLITICAL TRENDS IN THE ITALIAN-AMERICAN MEDIA DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF FASCISM by Ryan J. Antonucci Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2013 Changing Perceptions of il Duce Tracing Political Trends in the Italian-American Media during the Early Years of Fascism Ryan J. Antonucci I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Ryan J. Antonucci, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Brian Bonhomme, Committee Member Date Dr. Martha Pallante, Committee Member Date Dr. Carla Simonini, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Associate Dean of Graduate Studies Date Ryan J. Antonucci © 2013 iii ABSTRACT Scholars of Italian-American history have traditionally asserted that the ethnic community’s media during the 1920s and 1930s was pro-Fascist leaning. This thesis challenges that narrative by proving that moderate, and often ambivalent, opinions existed at one time, and the shift to a philo-Fascist position was an active process. Using a survey of six Italian-language sources from diverse cities during the inauguration of Benito Mussolini’s regime, research shows that interpretations varied significantly. One of the newspapers, Il Cittadino Italo-Americano (Youngstown, Ohio) is then used as a case study to better understand why events in Italy were interpreted in certain ways. -

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften Des Historischen Kollegs

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften des Historischen Kollegs Herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching Kolloquien 91 The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Herausgegeben von Holger Afflerbach An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Schriften des Historischen Kollegs herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching in Verbindung mit Georg Brun, Peter Funke, Karl-Heinz Hoffmann, Martin Jehne, Susanne Lepsius, Helmut Neuhaus, Frank Rexroth, Martin Schulze Wessel, Willibald Steinmetz und Gerrit Walther Das Historische Kolleg fördert im Bereich der historisch orientierten Wissenschaften Gelehrte, die sich durch herausragende Leistungen in Forschung und Lehre ausgewiesen haben. Es vergibt zu diesem Zweck jährlich bis zu drei Forschungsstipendien und zwei Förderstipendien sowie alle drei Jahre den „Preis des Historischen Kollegs“. Die Forschungsstipendien, deren Verleihung zugleich eine Auszeichnung für die bisherigen Leis- tungen darstellt, sollen den berufenen Wissenschaftlern während eines Kollegjahres die Möglich- keit bieten, frei von anderen Verpflichtungen eine größere Arbeit abzuschließen. Professor Dr. Hol- ger Afflerbach (Leeds/UK) war – zusammen mit Professor Dr. Paul Nolte (Berlin), Dr. Martina Steber (London/UK) und Juniorprofessor Simon Wendt (Frankfurt am Main) – Stipendiat des Historischen Kollegs im Kollegjahr 2012/2013. Den Obliegenheiten der Stipendiaten gemäß hat Holger Afflerbach aus seinem Arbeitsbereich ein Kolloquium zum Thema „Der Sinn des Krieges. Politische Ziele und militärische Instrumente der kriegführenden Parteien von 1914–1918“ vom 21. -

FINE EUROPEAN CERAMICS Thursday 5 July 2018

FINE EUROPEAN CERAMICS Thursday 5 July 2018 SPECIALIST AND AUCTION ENQUIRIES EUROPEAN CERAMICS Sebastian Kuhn Nette Megens Sophie von der Goltz FINE EUROPEAN CERAMICS Thursday 5 July 2018 at 2pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES IMPORTANT INFORMATION Saturday 30 June 11am - 5pm Nette Megens Monday to Friday 8.30am The United States Government Sunday 1 July 11am - 5pm Head of Department to 6pm has banned the import of ivory Monday 2 July 9am - 4.30pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8348 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 into the USA. Lots containing Tuesday 3 July 9am - 4.30pm [email protected] ivory are indicated by the Wednesday 4 July 9am - 4.30pm Please see page 2 for bidder symbol Ф printed beside the Thursday 5 July by appointment Sebastian Kuhn information including after-sale lot number in this catalogue. Department Director collection and shipment SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 8384 REGISTRATION 24937 [email protected] PHYSICAL CONDITION OF IMPORTANT NOTICE LOTS IN THIS AUCTION Please note that all customers, CATALOGUE Sophie von der Goltz Please note that any reference in irrespective of any previous Specialist £25.00 this catalogue to the physical activity with Bonhams, are +44 (0) 20 7468 8349 condition of any lot is for general required to complete the [email protected] BIDS guidance only. Intending bidders Bidder Registration Form in +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 must satisfy themselves as to the advance of the sale. The form +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax International Director condition of any lot as specified in can be found at the back of To bid via the internet please European Ceramics & Glass clause 14 of the notice to bidders every catalogue and on our visit bonhams.com John Sandon contained at the end of this website at www.bonhams.com +44 (0) 20 7468 8244 catalogue. -

The Corporatism of Fascist Italy Between Words and Reality

CORPORATIVISMO HISTÓRICO NO BRASIL E NA EUROPA http://dx.doi.org/10.15448/1980-864X.2016.2.22336 The corporatism of Fascist Italy between words and reality O corporativismo da Itália fascista entre palavras e realidade El corporativismo de la Italia fascista entre las palabras y la realidad Alessio Gagliardi* Translated by Sergio Knipe Abstract: It is common knowledge that State intervention in Italy in the Twenties and the Thirties developed outside of corporative institutions. The history of Fascist corporatism, however, is not only an unsuccessful story. Despite the failure of the “corporatist revolution” and “Fascist third way”, Fascist corporatism since the mid- Twenties helped the progressive development of a new political system to regulate relationship between State and private interests. The paper examines not only the institutional framework (the systems of formal laws, regulations, and procedures, and informal norms) but also their acts and real activities. It dwells upon internal debates, political and institutional importance acquired by corporative institutions in Fascist regime and behaviours of entrepreneurial organizations and labour unions. In this way, the paper aims to point out the “real” consequences of Fascist corporatism, different from the ideological ones. Keywords: corporatism; Fascism; Italy Resumo: É de conhecimento geral que intervenções estatais na Itália nas décadas de 1920 e 1930 se desenvolveram fora de instituições corporativas. A história do corporativismo fascista, no entanto, não é totalmente sem sucessos. Apesar da falha da “revolução corporativista” e da “terceira via fascista”, o corporativismo fascista, desde meados dos anos 1920, ajudou no desenvolvimento progressivo de um novo sistema político para regular a relação entre o Estado e interesses privados. -

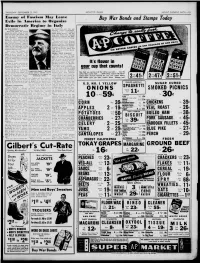

Gilbert S Cut-Rate I

THURSDAY—SEPTEMBER 23, 1943 MONITOR LEADER MOUNT CLEMENS, MICH 13 Ent k inv oh* May L« kav«* Buy War Bonds and Stamps Today Exile in i\meriea to Orijaiiixe w • ll€kiiioi*ralir hi Italy BY KAY HALLE ter Fiammetta. and his son Written for M A Service Sforzino reached Bordeaux, Within 25 year* the United where they m* to board a States has Riven refuge to two Dutch tramp steamer. For five great European Democrats who long days before they reached were far from the end of their Falmouth in England, the Sfor- rope politically. Thomas Mas- zas lived on nothing but orang- aryk. the Czech patriot, after es. a self-imposed exile on spending It war his old friend, Winston shores, return ! after World our Churchill, who finally received to it War I his homrlan after Sforza in London. the The Battle of had been freed from German Britain yoke—as the had commenced. Church- the President of approved to pro- newly-formed Republic—- ill Sforza side i Czech ceed to the United States and after modeled our own. keep the cause of Italian democ- Now, with the collapse of racy aflame. famous exile Italy, another HEADS “FREE ITALIANS” He -* an... JC. -a seems to be 01. the march. J two-year Sforza’-i American . is Count Carlo Sforza, for 20 exile has been spent in New’ years the uncompromising lead- apartment—- opposition York in a modest er of the Democratic that is, he not touring to Italy when is to Fascism. His return the country lecturing and or- imminent seem gazing the affairs of the 300,- Sforza is widely reg rded as in 000 It's flnuor Free Italians in the Western the one Italian who could re- Hemisphere, w hom \e leads construct a democratic form of His New York apartment is government for Italy. -

Il Fascismo Da Movimento a Regime

1919 1926 IL FASCISMO DA MOVIMENTO A REGIME Edizioni Fondazione Anna Kuliscioff Collana “La memoria degli uomini” Con il contributo di 1919 1926 IL FASCISMO DA MOVIMENTO A REGIME Pubblicazione a cura di Edizioni Fondazione Anna Kuliscioff via Vallazze, 34 20131 Milano www.fondazioneannakuliscioff.it [email protected] Progetto grafico e impaginazione Antonio Garonzi [email protected] Stampa T&D Service srl Corso Roma, 116 20811 Cesano Maderno (MB) [email protected] DIFFUSIONE GRATUITA ISBN 9788894332094 Tutti i diritti sono riservati. Nessuna parte di questa pubblicazione può essere utilizzata, riprodotta o diffusa con un mezzo qualsiasi senza autorizzazione della casa editrice 1919 1926 IL FASCISMO DA MOVIMENTO A REGIME INTRODUZIONE on la pubblicazione di questa “cronologia ragionata” di un periodo cruciale della storia italiana, che accompagna la Mostra: “1919 - 1926. Il fascismo da movimento a regime”, la Fondazione Anna Kuliscioff intende offrire a chiunque ne sia interessato, in particolare ai giovani, una selezione Ctemporale degli eventi più significativi che accompagnarono il nascere e l’affermarsi del fascismo con il commento di protagonisti di quel tempo e con l’opinione di alcuni dei più importanti storici. Ci è sembrato utile presentare i materiali documentari che illustrano come il fascismo, da composito movimento rivoluzionario come appare evidente dal programma del marzo del 1919 di piazza San Sepolcro a Milano nel 1919, si trasformi definitivamente al congresso dell’Augusteo a Roma nel novembre 1922, in cui viene costituito il Partito Nazionale Fascista, in una forza conservatrice, non solo antisocialista ma anche antiproletaria. L’appoggio degli agrari e di una parte degli industriali, ma soprattutto il consenso di vasti settori dei ceti medi costituì la base sociale del fascismo su cui esercitò una notevole attrazione l’ideologia stessa dello stato totalitario che il fascismo andava costruendo. -

Fascist Italy's Illiberal Cultural Networks Culture, Corporatism And

Genealogie e geografie dell’anti-democrazia nella crisi europea degli anni Trenta Fascismi, corporativismi, laburismi a cura di Laura Cerasi Fascist Italy’s Illiberal Cultural Networks Culture, Corporatism and International Relations Benjamin G. Martin Uppsala University, Sweden Abstract Italian fascists presented corporatism, a system of sector-wide unions bring- ing together workers and employers under firm state control, as a new way to resolve tensions between labour and capital, and to reincorporate the working classes in na- tional life. ‘Cultural corporatism’ – the fascist labour model applied to the realm of the arts – was likewise presented as a historic resolution of the problem of the artist’s role in modern society. Focusing on two art conferences in Venice in 1932 and 1934, this article explores how Italian leaders promoted cultural corporatism internationally, creating illiberal international networks designed to help promote fascist ideology and Italian soft power. Keywords Fascism. Corporatism. State control. Labour. Capital. Summary 1 Introduction. – 2 Broadcasting Cultural Corporatism. – 3 Venice 1932: Better Art Through Organisation. – 4 Italy’s International Cultural Outreach: Strategies and Themes. – 5 Venice 1934: Art and the State, Italy and the League. – 6 Conclusion. 1 Introduction The great ideological conflict of the interwar decades was a clash of world- views and visions of society, but it also had a quite practical component: which ideology could best respond to the concrete problems of the age? Problems like economic breakdown, mass unemployment, and labour unrest were not only practical, of course: they seemed linked to a broader breakdown of so- Studi di storia 8 e-ISSN 2610-9107 | ISSN 2610-9883 ISBN [ebook] 978-88-6969-317-5 | ISBN [print] 978-88-6969-318-2 Open access 137 Published 2019-05-31 © 2019 | cb Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License DOI 10.30687/978-88-6969-317-5/007 Martin Fascist Italy’s Illiberal Cultural Networks. -

Between the Local and the National: the Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2014 Between the Local and the National: The Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty Fabio Capano Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Capano, Fabio, "Between the Local and the National: The Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty" (2014). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5312. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5312 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between the Local and the National: the Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianità," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty Fabio Capano Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Modern Europe Joshua Arthurs, Ph.D., Co-Chair Robert Blobaum, Ph.D., Co-Chair Katherine Aaslestad, Ph.D. -

Sicily and the Surrender of Italy

United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations Sicily and the Surrender of Italy by Albert N. Garland and Howard McGaw Smyth Assisted by Martin Blumenson CENTER OF MILITARY HISTORY UNITED STATES ARMY WASHINGTON, D.C., 1993 Chapter XIV The Climax Sardinia Versus the Mainland The successful invasion of Sicily clarified strategic problems and enabled the Allies to turn from debate to decision. The Combined Chiefs of Staff at the TRIDENT Conference in May had directed General Eisenhower to knock Italy out of the war and contain the maximum number of German forces, but they had not told him how. Preparing to launch operations beyond the Sicilian Campaign, AFHQ had developed several outline plans: BUTTRESS, invasion of the Italian toe by the British 10 Corps; GOBLET, a thrust at the ball of the Italian foot by the British 5 Corps; BRIMSTONE, invasion of Sardinia; and FIREBRAND, invasion of Corsica. But a firm decision on the specific course of action to be taken was still lacking.1 The four plans, Eisenhower had explained to Churchill during the Algiers meetings in June, pointed to two broad alternative courses. If the Axis resisted vigorously in Sicily, thereby forecasting high Italian morale and a bitter and protracted struggle for the Allies, then BRIMSTONE and FIREBRAND, insular operations, were preferable. Otherwise, operations on the Italian mainland were more promising. Despite Churchill's articulate enthusiasm for the latter course, Eisenhower had made no commitment. He awaited the factual evidence to be furnished in Sicily. Meanwhile, the Americans and British continued to argue over strategy. -

Appendix: Einaudi, President of the Italian Republic (1948–1955) Message After the Oath*

Appendix: Einaudi, President of the Italian Republic (1948–1955) Message after the Oath* At the general assembly of the House of Deputies and the Senate of the Republic, on Wednesday, 12 March 1946, the President of the Republic read the following message: Gentlemen: Right Honourable Senators and Deputies! The oath I have just sworn, whereby I undertake to devote myself, during the years awarded to my office by the Constitution, to the exclusive service of our common homeland, has a meaning that goes beyond the bare words of its solemn form. Before me I have the shining example of the illustrious man who was the first to hold, with great wisdom, full devotion and scrupulous impartiality, the supreme office of head of the nascent Italian Republic. To Enrico De Nicola goes the grateful appreciation of the whole of the people of Italy, the devoted memory of all those who had the good fortune to witness and admire the construction day by day of the edifice of rules and traditions without which no constitution is destined to endure. He who succeeds him made repeated use, prior to 2 June 1946, of his right, springing from the tradition that moulded his sentiment, rooted in ancient local patterns, to an opinion on the choice of the best regime to confer on Italy. But, in accordance with the promise he had made to himself and his electors, he then gave the new republican regime something more than a mere endorsement. The transition that took place on 2 June from the previ- ous to the present institutional form of the state was a source of wonder and marvel, not only by virtue of the peaceful and law-abiding manner in which it came about, but also because it offered the world a demonstration that our country had grown to maturity and was now ready for democracy: and if democracy means anything at all, it is debate, it is struggle, even ardent or * Message read on 12 March 1948 and republished in the Scrittoio del Presidente (1948–1955), Giulio Einaudi (ed.), 1956. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan)