Sicily and the Surrender of Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aiello Calabro (CS) Italy

Dr. Francesco Gallo OUTSTANDING FAMILIES of Aiello Calabro (CS) Italy from the XVI to the XX centuries EMIGRATION to USA and Canada from 1880 to 1930 Padua, Italy August 2014 1 Photo on front cover: Graphic drawing of Aiello of the XVII century by Pietro Angius 2014, an readaptation of Giovan Battista Pacichelli's drawing of 1693 (see page 6) Photo on page 1: Oil painting of Aiello Calabro by Rosario Bernardo (1993) Photo on back cover: George Benjamin Luks, In the Steerage, 1900 Oil on canvas 77.8 x 48.9 cm North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh. Purchased with funds from the Elizabeth Gibson Taylor and Walter Frank Taylor Fund and the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. Phifer Bequest), 98.12 2 With deep felt gratitude and humility I dedicate this publication to Prof. Rocco Liberti a pioneer in studying Aiello's local history and author of the books: "Ajello Calabro: note storiche " published in 1969 and "Storia dello Stato di Aiello in Calabria " published in 1978 The author is Francesco Gallo, a Medical Doctor, a Psychiatrist, a Professor at the University of Maryland (European Division) and a local history researcher. He is a member of various historical societies: Historical Association of Calabria, Academy of Cosenza and Historic Salida Inc. 3 Coat of arms of some Aiellese noble families (from the book by Cesare Orlandi (1734-1779): "Delle città d'Italia e sue isole adjacenti compendiose notizie", Printer "Augusta" in Perugia, 1770) 4 SUMMARY of the book Introduction 7 Presentation 9 Brief History of the town of Aiello Calabro -

The Second World War and the East Africa Campaign by Andrew Stewart

2017-076 9 Oct. 2017 The First Victory: The Second World War and the East Africa Campaign by Andrew Stewart. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2016. Pp. xvi, 308. ISBN 978–o–300–20855–9. Review by Paolo Morisi, Milan ([email protected]). The First Victory is a perceptive account of the triumph of British and Commonwealth (especially South African) forces over the Italians in East Africa in 1940–41. Though it was the first major victory of the British over Axis forces after Dunkirk, it was quickly overshadowed by events in North Africa and the Mediterranean. The book’s author, military historian Andrew Stewart (King’s College London), seeks to explain why British forces succeeded in this lesser known campaign of the Second World War. When the war broke out, Africa Orientale Italiana (Italian East Africa) consisted of present-day Er- itrea and Ethiopia, which were surrounded by the British Empire territories of Somaliland and Sudan. The campaign started in earnest in summer 1940, when the Italians launched surprise air and infantry attacks against British air bases and defensive positions. It ended with a final smashing Allied victory. Beginning in November 1941, small groups of Italians and locals fought a guerrilla war in Ethiopia, but all hostilities ceased when Italy and the Allies signed the Armistice of Cassibile (3 Sept. 1943). Stewart, a specialist in British battlefield strategy and tactics, first discusses the organization of the Italian and British/Commonwealth troops in East Africa at the outbreak of the war. He stresses that the British, who lacked heavy artillery, were wholly unprepared for a major conflict. -

Il Fascismo Da Movimento a Regime

1919 1926 IL FASCISMO DA MOVIMENTO A REGIME Edizioni Fondazione Anna Kuliscioff Collana “La memoria degli uomini” Con il contributo di 1919 1926 IL FASCISMO DA MOVIMENTO A REGIME Pubblicazione a cura di Edizioni Fondazione Anna Kuliscioff via Vallazze, 34 20131 Milano www.fondazioneannakuliscioff.it [email protected] Progetto grafico e impaginazione Antonio Garonzi [email protected] Stampa T&D Service srl Corso Roma, 116 20811 Cesano Maderno (MB) [email protected] DIFFUSIONE GRATUITA ISBN 9788894332094 Tutti i diritti sono riservati. Nessuna parte di questa pubblicazione può essere utilizzata, riprodotta o diffusa con un mezzo qualsiasi senza autorizzazione della casa editrice 1919 1926 IL FASCISMO DA MOVIMENTO A REGIME INTRODUZIONE on la pubblicazione di questa “cronologia ragionata” di un periodo cruciale della storia italiana, che accompagna la Mostra: “1919 - 1926. Il fascismo da movimento a regime”, la Fondazione Anna Kuliscioff intende offrire a chiunque ne sia interessato, in particolare ai giovani, una selezione Ctemporale degli eventi più significativi che accompagnarono il nascere e l’affermarsi del fascismo con il commento di protagonisti di quel tempo e con l’opinione di alcuni dei più importanti storici. Ci è sembrato utile presentare i materiali documentari che illustrano come il fascismo, da composito movimento rivoluzionario come appare evidente dal programma del marzo del 1919 di piazza San Sepolcro a Milano nel 1919, si trasformi definitivamente al congresso dell’Augusteo a Roma nel novembre 1922, in cui viene costituito il Partito Nazionale Fascista, in una forza conservatrice, non solo antisocialista ma anche antiproletaria. L’appoggio degli agrari e di una parte degli industriali, ma soprattutto il consenso di vasti settori dei ceti medi costituì la base sociale del fascismo su cui esercitò una notevole attrazione l’ideologia stessa dello stato totalitario che il fascismo andava costruendo. -

Comparative Political Reactions in Spain from the 1930S to the Present

Comparative Political Reactions in Spain from the 1930s to the Present Undergraduate Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in Spanish in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Benjamin Chiappone The Ohio State University April 2020 Project Advisor: Professor Eugenia Romero, Department of Spanish and Portuguese Co-Advisor: Professor Ignasi Gozalo-Salellas, Department of Spanish and Portuguese Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………3 1. The Franco Regime • Francoism & Fascist European Counterparts…………………………………………6 • Franco & the Coup d’état……………………………………………………10 • Memory of the Dictatorship…………………………………………………...12 2. Left-Wing Reactions • CNT & Anarchist Traditions…………………………………………14 • ETA’s Terrorism………………………………………………………………21 • The Catatonia Crisis…………………………………………………………31 • Catalonia & Protest Through the 1992 Olympic Games…………………..35 3. VOX: a Right-Wing Reaction • VOX’s Success & Politics……………………………..…………………...41 Conclusion……………………………………………………..……………..50 2 Introduction George Santayana, a 20th century philosopher once said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” In Spain’s Pacto de Olvido, the goal was just that, to forget. The pact was initially a political decision, but was given legal legitimacy in the Ley De Amnistía. The decree prevented any accountability for the people who were killed, tortured, and exiled during the civil war. It pardoned those (even far-right military commanders) who were involved in the regime, allowed those who were exiled to return to Spain, and has prevented the nation from investigating human rights violations under the dictatorship. Further, the pact prevented any observation of the war or any commission to look into who bore responsibility for the war (Encarnación). Regardless, memory is crucial in order to understand the past of a nation and its trajectory moving forward. -

From the Adriatic to the Black Sea: the Italian Economic and Military Expansion Endeavour in the Balkan-Danube Area

Studies in Political and Historical Geography Vol. 8 (2019): 117–137 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/2300-0562.08.07 Corrado Montagnoli From the Adriatic to the Black Sea: The Italian economic and military expansion endeavour in the Balkan-Danube area Abstract: During the years that followed the end of the Great War, the Adriatic area found itself in a period of deep economic crisis due to the emptiness caused by the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The ancient Habsburg harbours, which had recently turned Italian, had lost their natural positions of Mitteleuropean economic outlets toward the Mediterranean due to the new political order of Central-Eastern Europe. Rome, then, attempted a series of economic manoeuvres aimed at improving Italian trade in the Julian harbours, first of all the port of Trieste, and at encouraging Italian entrepreneurial penetration in the Balkans. Resolved in a failure, the desire for commercial boost toward the oriental Adriatic shore coincided with the Dalmatian Irredentism and became a topic for claiming the 1941 military intervention across the Balkan peninsula. Italian geopoliticians, who had just developed the geopolitical discipline in Italy, made the Adriatic-Balkan area one of their most discussed topics. The fascist geopolitical project aimed at creating an economic aisle between the Adriatic and the Black Sea, in order to bypass the Turkish straits and become completion and outlet toward the Mediterranean of the Nazi Baltic-Mitteleuropean space in the north. Rome attempted the agreement with the other Danubian States, which subscribed the Tripartite Pact, in order to create a kind of economic cooperation area under the Italian lead. -

PREMESSA Nel 1969 E Nel 1970 L'ufficio Storico Dello Stato Maggiore Dell'esercito Mi La Cortesemente Concesso Di Esaminare I

L’ALTO COMANDO DA BADOGLIO A CAVALLERO (1925- 1941) PREMESSA Nel 1969 e nel 1970 l’Ufficio storico dello Stato maggiore dell’esercito mi La cortesemente concesso di esaminare il Diario del maresciallo Cavallero e al tresì di estrarre copia di parti di esso e dei suoi allegati da me indicati. L’Uf ficio, cui va un caloroso ringraziamento, ha prestato la propria organizzazione in modo da facilitare al massimo i miei studi. Da questo esame è nata in un primo tempo una comunicazione presentata al congresso internazionale or ganizzato a Parigi nell’aprile 1969 dal Comité d’histoire de la 2e guerre mon diale. La comunicazione, intitolata Quelques aspects de l'activité du haut com mandement italien dans la guerre en Mediterranée (mai 1941-août 1942), è ora pubblicata nel volume La guerre en Mediterranée edito nel 1971 dal Centre national de la Recherche scientifique. Successivamente, per incarico dell’Istituto nazionale per la storia del movimento di liberazione, ho intrapreso la stesura di un più ampio lavoro la cui redazione è tuttora in corso e del quale quanto qui pubblicato costituirà il primo capitolo. Il Diario Cavallero consiste di 27 volumi dattiloscritti (diario vero e pro prio) e di 27 fascicoli di documenti allegati, corrispondenti all’incirca ai mesi in cui Cavallero resse la carica di capo di Stato maggiore generale (dicembre 1940-gennaio 1943). Vi è inoltre un particolare fascicolo-documenti dedicato alla visita di Mussolini in Albania del marzo 1941. Un estratto del Diario, as sieme con taluni brani di allegati, è stato curato dall’avv. Giuseppe Bucciante che lo pubblicò nel 1948 presso l’editore Cappelli di Bologna con il titolo Comando supremo. -

Inventing the Lesser Evil in Italy and Brazil

Fascist Fiction: Inventing the Lesser Evil in Italy and Brazil by Giulia Riccò Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Lamonte Aidoo, Supervisor ___________________________ Roberto Dainotto ___________________________ Nicola Gavioli ___________________________ Saskia Ziolkowski Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 i v ABSTRACT Fascist Fiction: Inventing the Lesser Evil in Italy and Brazil by Giulia Riccò Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Lamonte Aidoo, Supervisor ___________________________ Roberto Dainotto ___________________________ Nicola Gavioli ___________________________ Saskia Ziolkowski An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by Giulia Riccò 2019 Abstract My dissertation, Fascist Fiction: Inventing the Lesser Evil in Italy and Brazil, accounts for the resilience of fascism by tracing the rhetoric of the “lesser evil”—a discursive practice constitutive of fascism—through contemporary politics and literature in Italy and Brazil. By invoking the looming presence of a graver, more insidious threat the rhetoric of the lesser evil legitimizes fascist violence against dissidents and vulnerable populations. Through an analysis of texts by fascist philosopher Giovanni Gentile and his Brazilian counterpart Miguel Reale, I reveal that the rhetoric of the lesser evil is a constitutive part of fascist discourse and that in Italy and Brazil this aspect of fascist doctrine met a favorable combination of subjective and objective conditions which has allowed it to thrive within democratic structures. -

Foreign News: Where Is Signor X?

Da “Time”, 24 maggio 1943 Foreign News: Where is Signor X? Almost 21 years of Fascism has taught Benito Mussolini to be shrewd as well as ruthless. Last week he toughened the will of his people to fight, by appeals to their patriotism, and by propaganda which made the most of their fierce resentment of British and U.S. bombings. He also sought to reduce the small number pf Italians who might try to cut his throat by independent deals with the Allies. The military conquest of Italy may be no easy task. After the Duce finished his week's activities, political warfare against Italy looked just as difficult, and it was hard to find an alternative to Mussolini for peace or postwar negotiations. No Dorlans. The Duce began by ticking off King Vittorio Emanuele, presumably as insurance against the unlikely prospect that the sour-faced little monarch decides either to abdicate or convert his House of Savoy into a bargain basement for peace terms. Mussolini pointedly recalled a decree of May 10, 1936, which elevated him to rank jointly with the King as "first marshal of Italy." Thus the King (constitutionally Commander in Chief of all armed forces) can legally make overtures to the Allies only with the consent and participation of the Duce. Italy has six other marshals. Mussolini last week recalled five of them to active service.* Most of these men had been disgraced previously to cover up Italian defeats. Some of them have the backing of financial and industrial groups which might desert Mussolini if they could make a better deal. -

La Voce. Etica E Politica Per Una Nuova Italia

TEMES La Voce. Etica e politica per una nuova Italia Simona Urso UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PADOVA a Voce rappresenta una delle riviste più feconde della stagione culturale e politica che in Italia viene definita come età giolittiana, L il periodo cioè che, a grandi linee occupa il primo quindicennio del ventesimo secolo; questa stagione della storia d’Italia è densa di produzione, in termini di progetti editoriali e di riviste culturali, ed è animata da un dibattito fondamentale per «leggere» la cultura italiana degli anni successivi. Per comprendere la ragione di tale effervescenza culturale è opportuno rammentare che l’Italia, alla svolta del secolo (La Voce nacque nel 1908), stava vivendo una profonda crisi culturale dovuta alla messa in discussione della corrente positivista, allora prevalente. Ma il paese usciva anche da una fase politica devastante, caratterizzata da una svolta autoritaria e dal fallimento italiano nell’impresa coloniale. Tale fallimento rendeva necessario, per molti giovani intellettuali che avrebbero dato vita alle riviste, un gesto di coraggio verso la svolta imperialista. E la situazione politica che si andò figurando, nei primi anni del ‘900, ne frustrò decisamente le aspettative. Dall’inizio del nuovo secolo, infatti, in particolare dal 1903 al 1914 (con occasionali dimissioni e rientri) fu al potere Giovanni Giolitti: la sua longevità politica, e le contraddizioni di quel periodo ci spingono a parlare di età giolittiana. Sono gli anni in cui nel paese, abbandonate le pretese 74 Simona Urso autoritarie di fine secolo, si affermò una linea di governo tendenzialmente progressista, caratterizzata da una nuova modalità di rapporti con le associazioni dei lavoratori e con il partito socialista, che pur non facendo mai parte del governo, spesso lo appoggiò. -

Cahiers De La Méditerranée, 88 | 2014 Italy, British Resolve and the 1935-1936 Italo-Ethiopian War 2

Cahiers de la Méditerranée 88 | 2014 Le rapport au monde de l'Italie de la première guerre mondiale à nos jours Italy, British resolve and the 1935-1936 Italo- Ethiopian War Jason Davidson Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cdlm/7428 DOI: 10.4000/cdlm.7428 ISSN: 1773-0201 Publisher Centre de la Méditerranée moderne et contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 30 June 2014 Number of pages: 69-84 ISSN: 0395-9317 Electronic reference Jason Davidson, « Italy, British resolve and the 1935-1936 Italo-Ethiopian War », Cahiers de la Méditerranée [Online], 88 | 2014, Online since 03 December 2014, connection on 08 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cdlm/7428 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/cdlm.7428 This text was automatically generated on 8 September 2020. © Tous droits réservés Italy, British resolve and the 1935-1936 Italo-Ethiopian War 1 Italy, British resolve and the 1935-1936 Italo-Ethiopian War Jason Davidson 1 As Italian elites prepared to attack Ethiopia in 1935 they knew that resolve mattered; they were aware that British willingness to incur costs to defend Ethiopia and the League of Nations would have a decisive impact on the war. If the British were to militarily oppose to Italy or even to close the Suez Canal, the Italian war effort would be prohibitively costly and would probably fail. Moreover, the British sent signals that could have been interpreted as evidence of high resolve (a willingness to incur great costs to defend Ethiopia and the League of Nations). In mid-September Foreign Secretary Samuel Hoare made an impassioned pledge that Britain would be “second to none” in defending its League obligations. -

Military History of Italy During World War II from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Military history of Italy during World War II From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The participation of Italy in the Second World War was characterized by a complex framework of ideology, politics, and diplomacy, while its military actions were often heavily influenced by external factors. The imperial ambitions of the Fascist regime, which aspired to restore the Roman Empire in North Africa and the Mediterranean (the Mare Nostrum, or the Italian Empire), were partially met with the annexation of Albania and the Province of Ljubljana, and the occupation of British Somaliland and other territories, but ultimately collapsed after defeats in the East and North African campaigns. In July 1943, following the Allied invasion of Sicily, Italy and its colonies in May 1940 (Dodecanese islands Benito Mussolini was arrested by order of King and Tientsin concession in China are not shown) Victor Emmanuel III, provoking a civil war. Italy surrendered to the Allies at the end of the Italian Campaign. The northern half of the country was occupied by Germans with the fascists help and made a collaborationist puppet state (with more than 600,000 soldiers), while the south was governed by monarchist and liberal forces, which fought for the Allied cause as the Italian Co-Belligerent Army (at its height numbering more than 50,000 men), helped by circa 350,000[1] partisans of disparate political ideologies that operated all over Italy. Contents 1 Background 1.1 Imperial ambitions 1.2 Industrial strength 1.3 Economy 1.4 Military 2 Outbreak of the Second World -

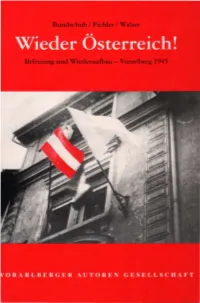

Wieder Österreich-Ocr Verr.Pdf

Bundschuh / Pichler / Walser Wieder Österreich! Befreiung und Wiederaufbau - Vorarlberg 1945 Herausgegeben von der Johann-August-Malin-Gesellschaft. Gefördert vom Land Vorarlberg. Johann A. Malin (1902 - 1942) Die Johann-August-Malin-Gesellschaft ist ein historischer Verein, be nannt nach dem 1942 in München-Stadelheim hingerichteten Vorarlberger Widerstandskämpfer Johann August Malin. Das Ziel des Vereins ist die Erforschung und Dokumentation der regionalen Zeit geschichte. Werner Bundschuh / Meinrad Pichler / HaraldWalser Wieder Österreich! Befreiung und Wiederaufbau -Vorarlberg 1945 VORARLBERGER AUTOREN GESELLSCHAFT Titelmotiv: Der weißen Fahne folgt die österreichische. Bregenz, am 1. Mai 1945. Foto: Archiv der Landeshauptstadt Bregenz © Vorarlberger Autoren Gesellschaft, Bregenz 1995 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Produktion: Werner Dreier, Bregenz Druck und Bindung: J.N. Teutsch, Bregenz Printed in Austria ISBN 3-900754-16-0 Inhalt Befreiung und Wiederaufbau - Vorarlberg 1945 Vorbemerkungen (Meinrad Pichler), S. 7 Meinrad Pichler: Am Ende eines Irrwegs, S.13 Harald Walser: Vorarlbergs Startbedingungen in die Zweite Republik, S. 39 Wemer Bundschuh: Das befreite Land - Die "Besatzungszeit", S. 59 Abkürzungen, S. 113 Literatur, S. 114 Bildquellennachweis, S. 119 Befreiung und Wiederaufbau - Vorarlberg 1945 Vorbemerkungen Den Anlaß für diese Broschüre gibt das Datum, ihre Notwendigkeit diktieren die aktuellen politischen Verhältnisse und den Inhalt bestimmt unsere Absicht aufzuklären. 50 Jahre nach dem Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges und 50 Jahre nach der Befreiung vom Hitler-Faschismus tun sich viele Östereicher immer noch schwer damit, die alliierten Truppen, die zwischen Ende April und Anfang Mai 1945 in Österreich einmarschierten, als Befreier anzuse hen. Dies resultiert aus einer schwierigen historischen Selbstzuordnung der Österreicher bis hin zum Jahre 1938 und ihrer daraus erwachsenen ambivalenten Stellung innerhalb des nationalsozialistischen Deutsch land.