JENS PETERSEN the Italian Aristocracy, the Savoy Monarchy, and Fascism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter One: Introduction

CHANGING PERCEPTIONS OF IL DUCE TRACING POLITICAL TRENDS IN THE ITALIAN-AMERICAN MEDIA DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF FASCISM by Ryan J. Antonucci Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2013 Changing Perceptions of il Duce Tracing Political Trends in the Italian-American Media during the Early Years of Fascism Ryan J. Antonucci I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Ryan J. Antonucci, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Brian Bonhomme, Committee Member Date Dr. Martha Pallante, Committee Member Date Dr. Carla Simonini, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Associate Dean of Graduate Studies Date Ryan J. Antonucci © 2013 iii ABSTRACT Scholars of Italian-American history have traditionally asserted that the ethnic community’s media during the 1920s and 1930s was pro-Fascist leaning. This thesis challenges that narrative by proving that moderate, and often ambivalent, opinions existed at one time, and the shift to a philo-Fascist position was an active process. Using a survey of six Italian-language sources from diverse cities during the inauguration of Benito Mussolini’s regime, research shows that interpretations varied significantly. One of the newspapers, Il Cittadino Italo-Americano (Youngstown, Ohio) is then used as a case study to better understand why events in Italy were interpreted in certain ways. -

Irredentismo

I percorsi dell’ Irredentismo e della Grande Guerra nella Provincia di Trieste a cura di Fabio Todero Volume pubblicato con il contributo della Provincia di Trieste nell’ambito degli interventi in ambito culturale dedicati alla “Valorizzazione complessiva del territorio e dei suoi siti di pregio” e con il patrocinio del Comune di Trieste Partner di progetto: Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche e Sociali dell’Università degli Studi di Trieste Deputazione di Storia Patria per la Venezia Giulia Istituto regionale per la cultura istriana, fiumana e dalmata Associazione culturale Zenobi, Trieste © copyright 2014 by Istituto regionale per la storia del movimento di liberazione nel Friuli Venezia Giulia Ricerche fotografiche: Michele Pupo Referenze fotografiche: Fototeca dei Civici Musei di Storia ed Arte del Comune di Trieste; Michele Pupo; Archivio E. Mastrociani, F. Todero; Archivio Divulgando Srl Progetto grafico: Divulgando Srl Istituto regionale per la storia del movimento di liberazione nel Friuli Venezia Giulia Villa Primc, Salita di Gretta 38 34136 Trieste Tel. / fax +39 040 44004 www.irsml.eu e-mail: [email protected] I percorsi dell’ Irredentismo e della Grande Guerra nella Provincia di Trieste a cura di Fabio Todero 2| Indice Introduzione I percorsi dell’Irredentismo e della Grande Guerra di Fabio Todero 1. Le Rive di Fabio Todero 2. Il Palazzo della Prefettura di Diego Caltana 3. Il Colle di San Giusto di Fabio Todero 4. Il Civico Museo del Risorgimento e il Sacrario Oberdan di Fabio Todero 5. Il Liceo-ginnasio Dante Alighieri di Fabio Todero 6. I cimiteri di S. Anna e di Servola di Fabio Todero 7. -

Sources for Genealogical Research at the Austrian War Archives in Vienna (Kriegsarchiv Wien)

SOURCES FOR GENEALOGICAL RESEARCH AT THE AUSTRIAN WAR ARCHIVES IN VIENNA (KRIEGSARCHIV WIEN) by Christoph Tepperberg Director of the Kriegsarchiv 1 Table of contents 1. The Vienna War Archives and its relevance for genealogical research 1.1. A short history of the War Archives 1.2. Conditions for doing genealogical research at the Kriegsarchiv 2. Sources for genealogical research at the Kriegsarchiv 2. 1. Documents of the military administration and commands 2. 2. Personnel records, and records pertaining to personnel 2.2.1. Sources for research on military personnel of all ranks 2.2.2. Sources for research on commissioned officers and military officials 3. Using the Archives 3.1. Regulations for using personnel records 3.2. Visiting the Archives 3.3. Written inquiries 3.4. Professional researchers 4. Relevant publications 5. Sources for genealogical research in other archives and institutions 5.1. Sources for genealogical research in other departments of the Austrian State Archives 5.2. Sources for genealogical research in other Austrian archives 5.3. Sources for genealogical research in archives outside of Austria 5.3.1. The provinces of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and its “successor states” 5.3.2. Sources for genealogical research in the “successor states” 5.4. Additional points of contact and practical hints for genealogical research 2 1. The Vienna War Archives and its relevance for genealogical research 1.1. A short history of the War Archives Today’s Austrian Republic is a small country, but from 1526 to 1918 Austria was a great power, we can say: the United States of Middle and Southeastern Europe. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

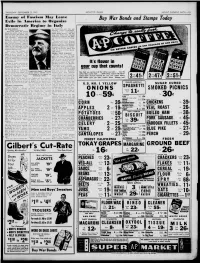

Gilbert S Cut-Rate I

THURSDAY—SEPTEMBER 23, 1943 MONITOR LEADER MOUNT CLEMENS, MICH 13 Ent k inv oh* May L« kav«* Buy War Bonds and Stamps Today Exile in i\meriea to Orijaiiixe w • ll€kiiioi*ralir hi Italy BY KAY HALLE ter Fiammetta. and his son Written for M A Service Sforzino reached Bordeaux, Within 25 year* the United where they m* to board a States has Riven refuge to two Dutch tramp steamer. For five great European Democrats who long days before they reached were far from the end of their Falmouth in England, the Sfor- rope politically. Thomas Mas- zas lived on nothing but orang- aryk. the Czech patriot, after es. a self-imposed exile on spending It war his old friend, Winston shores, return ! after World our Churchill, who finally received to it War I his homrlan after Sforza in London. the The Battle of had been freed from German Britain yoke—as the had commenced. Church- the President of approved to pro- newly-formed Republic—- ill Sforza side i Czech ceed to the United States and after modeled our own. keep the cause of Italian democ- Now, with the collapse of racy aflame. famous exile Italy, another HEADS “FREE ITALIANS” He -* an... JC. -a seems to be 01. the march. J two-year Sforza’-i American . is Count Carlo Sforza, for 20 exile has been spent in New’ years the uncompromising lead- apartment—- opposition York in a modest er of the Democratic that is, he not touring to Italy when is to Fascism. His return the country lecturing and or- imminent seem gazing the affairs of the 300,- Sforza is widely reg rded as in 000 It's flnuor Free Italians in the Western the one Italian who could re- Hemisphere, w hom \e leads construct a democratic form of His New York apartment is government for Italy. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

A British Reflection: the Relationship Between Dante's Comedy and The

A British Reflection: the Relationship between Dante’s Comedy and the Italian Fascist Movement and Regime during the 1920s and 1930s with references to the Risorgimento. Keon Esky A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. University of Sydney 2016 KEON ESKY Fig. 1 Raffaello Sanzio, ‘La Disputa’ (detail) 1510-11, Fresco - Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican. KEON ESKY ii I dedicate this thesis to my late father who would have wanted me to embark on such a journey, and to my partner who with patience and love has never stopped believing that I could do it. KEON ESKY iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis owes a debt of gratitude to many people in many different countries, and indeed continents. They have all contributed in various measures to the completion of this endeavour. However, this study is deeply indebted first and foremost to my supervisor Dr. Francesco Borghesi. Without his assistance throughout these many years, this thesis would not have been possible. For his support, patience, motivation, and vast knowledge I shall be forever thankful. He truly was my Virgil. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the whole Department of Italian Studies at the University of Sydney, who have patiently worked with me and assisted me when I needed it. My sincere thanks go to Dr. Rubino and the rest of the committees that in the years have formed the panel for the Annual Reviews for their insightful comments and encouragement, but equally for their firm questioning, which helped me widening the scope of my research and accept other perspectives. -

E42 Mark Blyth & David Kertzer Mixdown

Brown University Watson Institute | E42_Mark Blyth & David Kertzer_mixdown [MUSIC PLAYING] MARK BLYTH: Hello, and welcome to a special edition of Trending Globally. My name is Mark Blyth. Today, I'm interviewing David Kertzer. David is the former provost here at Brown University. But perhaps more importantly, he knows more about Italy than practically anybody else we can find. Given that the elections have just happened in Italy and produced yet another kind of populist shock, we thought is was a good idea to bring him in and have a chat. Good afternoon, David. DAVID KERTZER: Thanks for having me, Mark. MARK BLYTH: OK, so let's try and put this in context for people. Italy's kicked off. Now, we could talk about what's happening right now today, but to try and get some context on this, I want to take us back a little bit. This is not the first time the Italian political system-- indeed the whole Italian state-- has kind of blown up. I want to go back to 1994. That's the last time things really disintegrated. Start there, and then walk forward, so then we can talk more meaningfully about the election. So I'm going to invite you to just take us back to 1994. Tell us about what was going on-- the post-war political compact, and then [BLOWS RASPBERRY] the whole thing fell apart. DAVID KERTZER: Well, right after World War II, of course, it was a new political system-- the end of the monarchy. There is a republic. The Christian Democratic Party, very closely allied with the Catholic Church, basically dominated Italian politics for decades. -

Appendix: Einaudi, President of the Italian Republic (1948–1955) Message After the Oath*

Appendix: Einaudi, President of the Italian Republic (1948–1955) Message after the Oath* At the general assembly of the House of Deputies and the Senate of the Republic, on Wednesday, 12 March 1946, the President of the Republic read the following message: Gentlemen: Right Honourable Senators and Deputies! The oath I have just sworn, whereby I undertake to devote myself, during the years awarded to my office by the Constitution, to the exclusive service of our common homeland, has a meaning that goes beyond the bare words of its solemn form. Before me I have the shining example of the illustrious man who was the first to hold, with great wisdom, full devotion and scrupulous impartiality, the supreme office of head of the nascent Italian Republic. To Enrico De Nicola goes the grateful appreciation of the whole of the people of Italy, the devoted memory of all those who had the good fortune to witness and admire the construction day by day of the edifice of rules and traditions without which no constitution is destined to endure. He who succeeds him made repeated use, prior to 2 June 1946, of his right, springing from the tradition that moulded his sentiment, rooted in ancient local patterns, to an opinion on the choice of the best regime to confer on Italy. But, in accordance with the promise he had made to himself and his electors, he then gave the new republican regime something more than a mere endorsement. The transition that took place on 2 June from the previ- ous to the present institutional form of the state was a source of wonder and marvel, not only by virtue of the peaceful and law-abiding manner in which it came about, but also because it offered the world a demonstration that our country had grown to maturity and was now ready for democracy: and if democracy means anything at all, it is debate, it is struggle, even ardent or * Message read on 12 March 1948 and republished in the Scrittoio del Presidente (1948–1955), Giulio Einaudi (ed.), 1956. -

Revolting Peasants: Southern Italy, Ireland, and Cartoons in Comparative Perspective, 1860–1882*

IRSH 60 (2015), pp. 1–35 doi:10.1017/S0020859015000024 r 2015 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Revolting Peasants: Southern Italy, Ireland, and Cartoons in Comparative Perspective, 1860–1882* N IALL W HELEHAN School of History, Classics and Archaeology, University of Edinburgh William Robertson Wing, Old Medical School, Teviot Place, Edinburgh, EH8 9AG, UK E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Peasants in general, and rural rebels in particular, were mercilessly ridiculed in the satirical cartoons that proliferated in European cities from the mid-nineteenth century. There was more to these images than the age-old hostility of the townspeople for the peasant, and this article comparatively explores how cartoons of southern Italian brigands and rural Irish agitators helped shape a liberal version of what was modern by identifying what was not: the revolting peasant who engaged in ‘‘unmanly’’ violence, lacked self-reliance, and was in thrall to Catholic clergymen. During periods of unrest, distinctions between brigands, rebels, and the rural populations as a whole were not always clear in cartoons. Comparison suggests that derogatory images of peasants from southern Italy and Ireland held local peculiarities, but they also drew from transna- tional stereotypes of rural poverty that circulated widely due to the rapidly expanding European publishing industry. While scholarly debates inspired by postcolonial perspectives have previously emphasized processes of othering between the West and East, between the metropole and colony, it is argued here that there is also an internal European context to these relationships based on ingrained class and gendered prejudices, and perceptions of what constituted the centre and the periphery. -

Conservative Parties and the Birth of Democracy

Conservative Parties and the Birth of Democracy How do democracies form and what makes them die? Daniel Ziblatt revisits this timely and classic question in a wide-ranging historical narrative that traces the evolution of modern political democracy in Europe from its modest beginnings in 1830s Britain to Adolf Hitler’s 1933 seizure of power in Weimar Germany. Based on rich historical and quantitative evidence, the book offers a major reinterpretation of European history and the question of how stable political democracy is achieved. The barriers to inclusive political rule, Ziblatt finds, were not inevitably overcome by unstoppable tides of socioeconomic change, a simple triumph of a growing middle class, or even by working class collective action. Instead, political democracy’s fate surprisingly hinged on how conservative political parties – the historical defenders of power, wealth, and privilege – recast themselves and coped with the rise of their own radical right. With striking modern parallels, the book has vital implications for today’s new and old democracies under siege. Daniel Ziblatt is Professor of Government at Harvard University where he is also a resident fellow of the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies. He is also currently Fernand Braudel Senior Fellow at the European University Institute. His first book, Structuring the State: The Formation of Italy and Germany and the Puzzle of Federalism (2006) received several prizes from the American Political Science Association. He has written extensively on the emergence of democracy in European political history, publishing in journals such as American Political Science Review, Journal of Economic History, and World Politics. -

Ja Hobson's Approach to International Relations

J.A. HOBSON'S APPROACH TO INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: AN EXPOSITION AND CRITIQUE David Long Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor Of Philosophy in International Relations at the London School of Economics. UMI Number: U042878 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Disscrrlation Publishing UMI U042878 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis argues that Hobson’s approach to international relations coheres around his use of the biological analogy of society to an organism. An aspect of this ‘organic analogy’ - the theory of surplus value - is central to Hobson’s modification of liberal thinking on international relations and his reformulated ‘new liberal internationalism’. The first part outlines a theoretical framework for Hobson’s discussion of international relations. His theory of surplus value posits cooperation as a factor in the production of value understood as human welfare. The organic analogy links this theory of surplus value to Hobson’s holistic ‘sociology’. Hobson’s new liberal internationalism is an extension of his organic theory of surplus value.