World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile Banking

Automated teller machine "Cash machine" Smaller indoor ATMs dispense money inside convenience stores and other busy areas, such as this off-premise Wincor Nixdorf mono-function ATM in Sweden. An automated teller machine (ATM) is a computerized telecommunications device that provides the customers of a financial institution with access to financial transactions in a public space without the need for a human clerk or bank teller. On most modern ATMs, the customer is identified by inserting a plastic ATM card with a magnetic stripe or a plastic smartcard with a chip, that contains a unique card number and some security information, such as an expiration date or CVVC (CVV). Security is provided by the customer entering a personal identification number (PIN). Using an ATM, customers can access their bank accounts in order to make cash withdrawals (or credit card cash advances) and check their account balances as well as purchasing mobile cell phone prepaid credit. ATMs are known by various other names including automated transaction machine,[1] automated banking machine, money machine, bank machine, cash machine, hole-in-the-wall, cashpoint, Bancomat (in various countries in Europe and Russia), Multibanco (after a registered trade mark, in Portugal), and Any Time Money (in India). Contents • 1 History • 2 Location • 3 Financial networks • 4 Global use • 5 Hardware • 6 Software • 7 Security o 7.1 Physical o 7.2 Transactional secrecy and integrity o 7.3 Customer identity integrity o 7.4 Device operation integrity o 7.5 Customer security o 7.6 Alternative uses • 8 Reliability • 9 Fraud 1 o 9.1 Card fraud • 10 Related devices • 11 See also • 12 References • 13 Books • 14 External links History An old Nixdorf ATM British actor Reg Varney using the world's first ATM in 1967, located at a branch of Barclays Bank, Enfield. -

Electronic Cash in Hong Kong

1 Focus THEME ity of users to lock their cards. Early in 1992, NatWest began a trial of Mondex in BY I. CHRISTOPHERWESTLAND. MANDY KWOK, ]OSEPHINESHU, TERENCEKWOK AND HENRYHO, HONG KONG an office complex in London with a 'can- UNIVERSITYOF SCIENCE&TECHNOLOGY. HONG KONG * teen card' known as Byte. The Byte trial is still continuing with more than 5,000 INTRODUCTION I teller cash for a card and uses it until that people using the card in two office res- Asian business has long had a fondness value is exhausted. Visa plans to offer a taurants and six shops. By December of for cash. While the West gravitated toward reloadable card later. 1993, the Mondex card was introduced on purchases on credit - through cards or a large scale. Sourcing for Mondex sys- installments - Asia maintained its passion HISTORY tem components involves more than 450 for the tangible. Four-fifths of all trans- Mondex was the brainchild of two NatWest manufacturers in over 40 countries. In actions in Hong Kong are handled with bankers - Tim Jones and Graham Higgins. October of 1994, franchise rights were sold cash. It is into this environment that They began technology development in to the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Mondex International, the London based 1990 with electronics manufacturers in the Corporation Limited to cover the Asian purveyor of electronic smart cards, and UK, USA and Japan. Subsequent market region including Hong Kong, China, In- Visa International, the credit card giant, research with 47 consumer focus groups dia, Indonesia, Macau, Philippines, are currently competing for banks, con- in the US, France, Germany, Japan, Hong Singapore and Thailand. -

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities A Financial System That T OF EN TH M E A Financial System T T R R A E P A E S That Creates Economic Opportunities D U R E Y H T Nonbank Financials, Fintech, 1789 and Innovation Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation Nonbank Financials, Fintech, TREASURY JULY 2018 2018-04417 (Rev. 1) • Department of the Treasury • Departmental Offices • www.treasury.gov U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation Report to President Donald J. Trump Executive Order 13772 on Core Principles for Regulating the United States Financial System Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary Craig S. Phillips Counselor to the Secretary T OF EN TH M E T T R R A E P A E S D U R E Y H T 1789 Staff Acknowledgments Secretary Mnuchin and Counselor Phillips would like to thank Treasury staff members for their contributions to this report. The staff’s work on the report was led by Jessica Renier and W. Moses Kim, and included contributions from Chloe Cabot, Dan Dorman, Alexan- dra Friedman, Eric Froman, Dan Greenland, Gerry Hughes, Alexander Jackson, Danielle Johnson-Kutch, Ben Lachmann, Natalia Li, Daniel McCarty, John McGrail, Amyn Moolji, Brian Morgenstern, Daren Small-Moyers, Mark Nelson, Peter Nickoloff, Bimal Patel, Brian Peretti, Scott Rembrandt, Ed Roback, Ranya Rotolo, Jared Sawyer, Steven Seitz, Brian Smith, Mark Uyeda, Anne Wallwork, and Christopher Weaver. ii A Financial System That Creates Economic -

Report on Environmental and Social Responsibility 07

Report on Environmental and Social Responsibility 07 The bank for a changing world CONTENTS Statement from the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer 2 Compliance within BNP Paribas 81-86 Key figures 3-4 Dedicated teams 82-84 Group's activities in 2007 5-73 • Up-to-date standards 83 • Monitoring financial security mechanisms 83-84 Corporate & Investment Banking 6-21 Business continuity 85-86 Advisory and Capital Markets 11-16 • Organisation of continuity efforts 85 • Equities and Derivatives 11-12 • Operational management of business continuity plans 85-86 • Fixed Income 13-14 BNP Paribas and its stakeholders • Corporate Finance 15-16 87-158 Financing businesses 17-21 Organised dialogue with stakeholders 88-89 • Specialised Finance 17-19 Shareholder information 90-99 • Structured Finance 20-21 Human Resources development 100-126 French Retail Banking 22-33 • Group values underpinning HR management 100 • Human Resources policy framework 101-103 • Individual clients 25-27 • Key challenges of human resources management 104 • Entrepreneurs and freelance professionals 28-29 • Clearly identified operational challenges 105-126 • Corporate and institutional clients 30-32 • After-sales organisation 33 Relations with clients and suppliers 127-137 International Retail Services 34-47 • A closely-attuned relationship 127-132 • Socially Responsible Investment 132-136 • Personal Finance 37-38 • Supplier relations 137 • Equipment Solutions 39-40 Impact on the natural environment 138-150 • BancWest 41-42 • Areas 138-140 • Emerging Markets 43-47 • Levers -

Guía Para El Uso De Canales Electrónicos. Canal Cajeros Automáticos

GUIA PARA EL USO DE CANALES ELECTRONICOS CAJEROS AUTOMÁTICOS –ATM– INGENIERÍA DE PROCESOS INDICE INTRODUCCIÓN...........................................................................................................................................................3 1. CAJEROS AUTOMÁTICOS (ATM ) .............................................................................................................................5 1.1. Características y beneficios principales ............................................................................................................5 1.2. Operaciones Disponibles ...................................................................................................................................5 1.2.1. Extracción / Adelanto ..................................................................................................................................5 1.2.2. Link Pagos .....................................................................................................................................................5 1.2.3. Compras y Recargas .....................................................................................................................................5 1.2.4. Transferencias ..............................................................................................................................................5 1.2.5. Depósitos .....................................................................................................................................................5 -

Assessment and Review of Application of Responsibilities for Authorities

Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures Board of the International Organization of Securities Commissions Assessment and review of application of Responsibilities for authorities November 2015 This publication is available on the BIS website (www.bis.org) and the IOSCO website (www.iosco.org). © Bank for International Settlements and International Organization of Securities Commissions 2015. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is stated. ISBN 978-92-9197-376-7 (online) Contents 1. Executive summary ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Key findings of the assessment ........................................................................................................................ 2 2. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Broader context of the Responsibilities assessment ............................................................................... 4 2.2 Scope and objective of the Responsibilities assessment ....................................................................... 5 3. Methodology ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Política De Gerenciamento De Risco De Mercado Do Banco

ITAÚ UNIBANCO HOLDING S.A. CNPJ 60.872.504/0001-23 Companhia Aberta COMUNICADO AO MERCADO Tecnologia Bancária S.A. (TECBAN) – Novo Acordo de Acionistas Itaú Unibanco Holding S.A. (“Itaú Unibanco”) informa aos seus acionistas e ao mercado em geral que: 1. Determinadas subsidiárias do Itaú Unibanco (Itaú Unibanco S.A., Unibanco Negócios Imobiliários S.A., Banco Itauleasing S.A., Banco Itaucard S.A. e Intrag – Part. Administração e Participações Ltda.), em conjunto com o Grupo Banco do Brasil (por meio do Banco do Brasil e BB Banco de Investimentos S.A.), o Grupo Santander (por meio do Santander S.A. – Serviços Técnicos, Administrativos e de Corretagem de Seguros), o Grupo Bradesco (por meio do Banco Bradesco S.A., Banco Alvorada S.A. e Alvorada Cartões, Crédito, Financiamento e Investimentos S.A.), o Grupo HSBC (por meio do HSBC Bank Brasil S.A. – Banco Múltiplo), o Grupo Caixa (por meio da Caixa Participações S.A.) e o Grupo Citibank (por meio do Citibank N.A. – Filial Brasileira e Banco Citibank S.A.) (todos, em conjunto, denominados “Partes”), com a interveniência e anuência de Tecnologia Bancária S.A. (“TecBan”), Itaú Unibanco, Banco Santander (Brasil) S.A. e Caixa Econômica Federal, assinaram, em 17 de julho de 2014, um novo Acordo de Acionistas da TecBan (“Acordo de Acionistas”), o qual, tão logo entre em vigor, revogará e substituirá o acordo de acionistas vigente. 2. Além das disposições usuais em acordos de acionistas, como regras sobre governança e transferência de ações, o Acordo de Acionistas prevê que, em aproximadamente 4 (quatro) anos contados de sua entrada em vigor, as Partes deverão ter substituído parte de sua rede externa de Terminais de Autoatendimento (“TAA”) pelos TAAs da Rede Banco24Horas, que são e continuarão sendo geridos pela TecBan. -

Universidad Apec

UNIVERSIDAD APEC ESCUELA DE GRADUADOS Trabajo Final Para Optar Por El Titulo De: MAESTRÍA EN GERENCIA Y PRODUCTIVIDAD Tema: “Mejoras para la Optimización de la Funcionalidad en la Red de Cajeros Automáticos. Caso: Banco Popular Año 2011” Sustentante: Glenny W. Serrata García 2009-1883 Asesora: Ivelisse Comprés, MA, MsC, MBA. Santo Domingo, D.N. Agosto, 2011 “Mejoras para la Optimización de la Funcionalidad en la Red de Cajeros Automáticos. Caso: Banco Popular Año 2011” INDICE Págs. RESUMEN ..................................................................................................... ii DEDICATORIA ............................................................................................ iv INTRODUCCION ........................................................................................ 02 CAPITULO I: GENERALIDADES DE LA BANCA ELECTRÓNICA 1.1 Historia de los Cajeros Automáticos .......................................................... 06 1.1.2 Definición de Cajeros Automáticos ................................................... 08 1.1.3 Funcionalidad de los ATM ............................................................... 08 1.1.4 Diseño y Tipos de Cajeros Automáticos............................................ 10 1.1.5 Regulaciones de los ATMs ............................................................... 11 1.2 Nueva Tecnología en Cajeros Automáticos ................................................ 12 1.2.1 Cajero Automáticos de Autoservicio ................................................. 12 1.2.2 Primer Cajero Biométrico -

Study on the Implementation of Recommendation 97/489/EC

Study on the implementation of Recommendation 97/489/EC concerning transactions carried out by electronic payment instruments and in particular the relationship between holder and issuer Call for Tender XV/99/01/C FINAL REPORT – Part b) Appendices 20th March 2001 Study on the implementation of Recommendation 97/489/EC 1 APPENDICES Appendices 1. Methodology.................................................................................3 Appendices 2. Tables..........................................................................................28 Appendices 3. List of issuers and EPIs analysed and surveyed........................147 Appendices 4. General summary of each Work Package.................................222 Appendices 5. Reports country per country (separate documents) Study on the implementation of Recommendation 97/489/EC 2 Appendices 1 Methodology Study on the implementation of Recommendation 97/489/EC 3 Content of Appendices 1 1. Structure of the report ..............................................................................5 2. Route Map................................................................................................6 3. Methodology.............................................................................................7 4. Tools used..............................................................................................14 Study on the implementation of Recommendation 97/489/EC 4 1. The Structure of the Report The aims of the study were to investigate how far the 1997 Recommendation has been -

Relatório Anual De Meios Eletrônicos De Pagamento

Relatório Anual de Meios Eletrônicos de Pagamento Perspectivas e Tendências 2020 Perspectivas e Tendências 2020 e Tendências Perspectivas - Quem decide, está aqui! www.cardmonitor.com.br Relatório Anual de Meios Eletrônicos de Pagamento de Pagamento Eletrônicos Anual de Meios Relatório Estamos vivenciando um momento único no setor de A PUBLICAÇÃO LÍDER meios eletrônicos de pagamento. As transformações são intensas e cada vez mais rápidas. Ninguém sabe prever DO MERCADO DE MEIOS com precisão os próximos 2 ou 3 anos, mas temos a ELETRÔNICOS DE PAGAMENTO certeza de que nada será como antes. Players ineficien- tes e lentos perderão mercado para os mais ágeis que propuserem soluções inovadoras a partir de seus entu- siasmados times de colaboradores. 2020 será um ano de transição, pois muitas medidas relevantes como open banking, pagamentos instantâneos, LGPD e cadastro po- mais de 10 anos de muito sitivo estarão em processo de implantação. trabalho e dedicação! Pois bem, este Relatório traz a opinião de respeitados executivos do setor sobre as perspectivas e tendências para os próximos anos. Faz parte de nosso Serviço de Monitoração do Mercado de MEP, que inclui também os Flashes semanais, Relatórios mensais, Market Share trimestrais, Plantões, Análises, etc. Vale a pena você investir seu precioso tempo na leitura integral. As opiniões são muito ricas. Se estiver com tempo limitado, leia primeiro nosso resumo executivo (pgs. 167 a 181). Os depoimentos foram coletados em nosso Fórum de Inteligên- Quem decide, está aqui! cia de Mercado, ocorrido em 28 e 29 de novembro de 2019. Complementamos Cardmonitor lider esse trabalho com depoimentos inéditos coletados por meio de um questionário estruturado em janeiro de 2020. -

Financial Crisis Report Written and Edited by David M

PUBLISHED BY MIYOSHI LAW July 2018 INTERNATIONAL & EST ATE LAW PRACTICE Volume 1, Issue 81 Financial Crisis Report Written and Edited by David M. Miyoshi Advancing in a Time of Crisis Words of Wisdom: "You can succeed at anything, as long as you don’t Inside this issue: care who takes the credit” Ronald Reagan 1. Historic Singapore Meeting 2. Go West Young Man Historic Singapore Meeting and suggested that it may ease its sanctions on 3. Wedding IRS Loves North Korea prior to complete denuclearization 4. Cryptocurrency Geo-Political Weap- its Aftermath and that it will halt U.S.-South Korea military on exercises. 5. Is Harvard Racist? Except for the Great Depression, we are experiencing the most By affirming that "mutual confidence building economically unstable period in can promote the denuclearization of the Korean the history of the modern world. Peninsula," the statement indicated that the This period will be marked with United States is willing to accept the phased extreme fluctuations in the stock, approach to denuclearization that North Korea commodity and currency markets accompanied by severe and some- desires. In a phased approach, both sides would times violent social disruptions. offer incentives along the way to denucleariza- As is typical of such times, many tion, rather than the United States waiting until fortunes will be made and lost the process is complete before offering any during this period. After talking tradeoffs. For the time being, Trump empha- with many business owners, sized that sanctions would remain in effect, but executives, professionals and he said they could be removed when North government officials from around n June 12, President Trump and the world, the writer believes that Korea makes a certain degree of progress in its Kim Jong Un leader of North Korea denuclearization. -

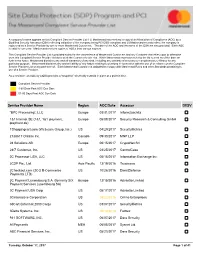

Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV

A company’s name appears on this Compliant Service Provider List if (i) Mastercard has received a copy of an Attestation of Compliance (AOC) by a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) reflecting validation of the company being PCI DSS compliant and (ii) Mastercard records reflect the company is registered as a Service Provider by one or more Mastercard Customers. The date of the AOC and the name of the QSA are also provided. Each AOC is valid for one year. Mastercard receives copies of AOCs from various sources. This Compliant Service Provider List is provided solely for the convenience of Mastercard Customers and any Customer that relies upon or otherwise uses this Compliant Service Provider list does so at the Customer’s sole risk. While Mastercard endeavors to keep the list current as of the date set forth in the footer, Mastercard disclaims any and all warranties of any kind, including any warranty of accuracy or completeness or fitness for any particular purpose. Mastercard disclaims any and all liability of any nature relating to or arising in connection with the use of or reliance on the Compliant Service Provider List or any part thereof. Each Mastercard Customer is obligated to comply with Mastercard Rules and other Standards pertaining to use of a Service Provider. As a reminder, an AOC by a QSA provides a “snapshot” of security controls in place at a point in time. Compliant Service Provider 1-60 Days Past AOC Due Date 61-90 Days Past AOC Due Date Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV “BPC Processing”, LLC Europe 03/31/2017 Informzaschita 1&1 Internet SE (1&1, 1&1 ipayment, Europe 05/08/2017 Security Research & Consulting GmbH ipayment.de) 1Shoppingcart.com (Web.com Group, lnc.) US 04/29/2017 SecurityMetrics 2138617 Ontario Inc.