Area Eandbook Laos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Module No. 1840 1840-1

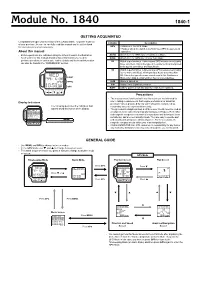

Module No. 1840 1840-1 GETTING ACQUAINTED Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To get the most out Indicator Description of your purchase, be sure to carefully read this manual and keep it on hand for later reference when necessary. GPS • Watch is in the GPS Mode. • Flashes when the watch is performing a GPS measurement About this manual operation. • Button operations are indicated using the letters shown in the illustration. AUTO Watch is in the GPS Auto or Continuous Mode. • Each section of this manual provides basic information you need to SAVE Watch is in the GPS One-shot or Auto Mode. perform operations in each mode. Further details and technical information 2D Watch is performing a 2-dimensional GPS measurement (using can also be found in the “REFERENCE” section. three satellites). This is the type of measurement normally used in the Quick, One-Shot, and Auto Mode. 3D Watch is performing a 3-dimensional GPS measurement (using four or more satellites), which provides better accuracy than 2D. This is the type of measurement used in the Continuous LIGHT Mode when data is obtained from four or more satellites. MENU ALM Alarm is turned on. SIG Hourly Time Signal is turned on. GPS BATT Battery power is low and battery needs to be replaced. Precautions • The measurement functions built into this watch are not intended for Display Indicators use in taking measurements that require professional or industrial precision. Values produced by this watch should be considered as The following describes the indicators that reasonably accurate representations only. -

Leonetti-Geo3.Pdf

GEO 3 Il Mondo: i paesaggi, la popolazione e l'economia 3 media:-testo di Geografia C3 pag. 2 Geo 3: Il Mondo I paesaggi, la popolazione, l’economia Per la Scuola Secondaria di Primo Grado a cura di Elisabetta Leonetti Coordinamento editoriale: Antonio Bernardo Ricerca iconografica: Cristina Capone Cartine tematiche: Studio Aguilar Copertina Ginger Lab - www.gingerlab.it Settembre 2013 ISBN 9788896354513 Progetto Educationalab Mobility IT srl Questo libro è rilasciato con licenza Creative Commons BY-SA Attribuzione – Non commerciale - Condividi allo stesso modo 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/legalcode Alcuni testi di questo libro sono in parte tratti da Wikipedia Versione del 11/11/2013 Modificato da [email protected] – 23/9/15 INDICE GEO 3 Glossario Mappe-Carte AulaVirtuale 3 media:-testo di Geografia C3 pag. 3 Presentazione Questo ebook fa parte di una collana di ebook con licenza Creative Commons BY-SA per la scuola. Il titolo Geo C3 vuole indicare che il progetto è stato realizzato in modalità Collaborativa e con licenza Creative Commons, da cui le tre “C” del titolo. Non vuole essere un trattato completo sull’argomento ma una sintesi sulla quale l’insegnante può basare la lezione, indicando poi testi e altre fonti per gli approfondimenti. Lo studente può consultarlo come riferimento essenziale da cui partire per approfondire. In sostanza, l’idea è stata quella di indicare il nocciolo essenziale della disciplina, nocciolo largamente condiviso dagli insegnanti. La licenza Creative Commons, con la quale viene rilasciato, permette non solo di fruire liberamente l’ebook ma anche di modificarlo e personalizzarlo secondo le esigenze dell’insegnante e della classe. -

Module No. 2240 2240-1

Module No. 2240 2240-1 GETTING ACQUAINTED Precautions • Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To get the most out The measurement functions built into this watch are not intended for of your purchase, be sure to carefully read this manual and keep it on hand use in taking measurements that require professional or industrial for later reference when necessary. precision. Values produced by this watch should be considered as reasonably accurate representations only. About This Manual • Though a useful navigational tool, a GPS receiver should never be used • Each section of this manual provides basic information you need to perform as a replacement for conventional map and compass techniques. Remember that magnetic compasses can work at temperatures well operations in each mode. Further details and technical information can also be found in the “REFERENCE”. below zero, have no batteries, and are mechanically simple. They are • The term “watch” in this manual refers to the CASIO SATELLITE NAVI easy to operate and understand, and will operate almost anywhere. For Watch (Module No. 2240). these reasons, the magnetic compass should still be your main • The term “Watch Application” in this manual refers to the CASIO navigation tool. • SATELLITE NAVI LINK Software Application. CASIO COMPUTER CO., LTD. assumes no responsibility for any loss, or any claims by third parties that may arise through the use of this watch. Upper display area MODE LIGHT Lower display area MENU On-screen indicators L K • Whenever leaving the AC Adaptor and Interface/Charger Unit SAFETY PRECAUTIONS unattended for long periods, be sure to unplug the AC Adaptor from the wall outlet. -

Cambodia Laos

COUNTRY REPORT Cambodia Laos 4th quarter 1997 The Economist Intelligence Unit 15 Regent Street, London SW1Y 4LR United Kingdom The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit is a specialist publisher serving companies establishing and managing operations across national borders. For over 50 years it has been a source of information on business developments, economic and political trends, government regulations and corporate practice worldwide. The EIU delivers its information in four ways: through subscription products ranging from newsletters to annual reference works; through specific research reports, whether for general release or for particular clients; through electronic publishing; and by organising conferences and roundtables. The firm is a member of The Economist Group. London New York Hong Kong The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit 15 Regent Street The Economist Building 25/F, Dah Sing Financial Centre London 111 West 57th Street 108 Gloucester Road SW1Y 4LR New York Wanchai United Kingdom NY 10019, USA Hong Kong Tel: (44.171) 830 1000 Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 Tel: (852) 2802 7288 Fax: (44.171) 499 9767 Fax: (1.212) 586 1181/2 Fax: (852) 2802 7638 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.eiu.com Electronic delivery EIU Electronic Publishing New York: Lou Celi or Lisa Hennessey Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 Fax: (1.212) 586 0248 London: Moya Veitch Tel: (44.171) 830 1007 Fax: (44.171) 830 1023 This publication is available on the following electronic and other media: Online databases CD-ROM Microfilm FT Profile (UK) Knight-Ridder Information World Microfilms Publications (UK) Tel: (44.171) 825 8000 Inc (USA) Tel: (44.171) 266 2202 DIALOG (USA) SilverPlatter (USA) Tel: (1.415) 254 7000 LEXIS-NEXIS (USA) Tel: (1.800) 227 4908 M.A.I.D/Profound (UK) Tel: (44.171) 930 6900 Copyright © 1997 The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited. -

Iron Man of Laos Prince Phetsarath Ratanavongsa the Cornell University Southeast Asia Program

* fll!!I ''{f'':" ' J.,, .,.,Pc, IRON MAN OF LAOS PRINCE PHETSARATH RATANAVONGSA THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM The Southeast Asia Program was organized at Cornell University in the Department of Far Eastern Studies in 1950. It is a teaching and research program of interdisciplinary studies in the humanities, social sciences, and some natural sciences. It deals with Southeast Asia as a region, and with the individual countries of the area: Brunei, Burma, Indonesia, Kampuchea, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. The activities of the Program are carried on both at Cornell and in Southeast Asia. They include an undergraduate and graduate curriculum at Cornell which provides instruction by specialists in Southeast Asian cultural history and present-day affairs and offers intensive training in each of the major languages of the area. The Program sponsors group research projects on Thailand, on Indonesia, on the Philippines, and on linguistic studies of the languages of the area. At the same time, individual staff and students of the Program have done field research in every Southeast Asian country. A list of publications relating to Southeast Asia which may be obtained on prepaid order directly from the Program is given at the end of this volume. Information on Program staff, fellowships, requirements for degrees, and current course offerings is obtainable· from the Director, Southeast Asia Program, 120 Uris Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853. 11 IRON MAN OF LAOS PRINCE PHETSARATH RATANAVONGSA by "3349" Trc1nslated by .John B. �1urdoch F.di ted by · David K. \-vyatt Data Paper: Number 110 -Southeast Asia Program Department of Asian Studies Cornell University, Ithaca, New York .November 197·8 Price: $5.00 111 CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM 1978 International Standard Book Number 0-87727-110-0 iv C.ONTENTS FOREWORD • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . -

The Tenth Congress of the Lao People's Revolutionary Party

Regime Renewal in Laos: The Tenth Congress of the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party Soulatha Sayalath and Simon Creak Introduction The year 2016 was a crucial one in Laos. According to an established five-yearly cycle, the year was punctuated by a series of key political events, foremost among them the Tenth Congress of the ruling Lao People’s Revolutionary Party (LPRP). As on past occasions, the Tenth Party Congress took stock of the country’s political and economic performance over the previous five years and adopted the country’s next five-year National Socio-Economic Development Plan. Most importantly, it also elected the new Party Central Committee (PCC), the party’s main decision-making body, together with the Politburo, PCC Secretariat and secretary-general. The congress was followed in March by elections for the National Assembly, which henceforth approved party nominations for the president and prime minister, who in turn appointed a new cabinet. Throughout this process, Laos occupied the chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), just its second time in the role, and in September played host to US President Barack Obama, the first sitting president to visit the country, when he joined the East Asia Summit. While all these events were important, most consequential was the process of party renewal that culminated with the congress. Given the LPRP’s grip on political power and the control its leaders exercise over Laos’ rich reserves of natural resources—the main source of the country’s rapid economic growth since the early 2000s—LPRP congresses represent critical moments of leadership renewal and transition. -

Read PDF \\ Geschichte Thailands // BKMPQK4EXNWD

9ADKEN5LH3NZ » Kindle # Geschichte Thailands Geschichte Thailands Filesize: 9.75 MB Reviews Great eBook and beneficial one. It is packed with wisdom and knowledge You wont really feel monotony at at any time of your respective time (that's what catalogs are for relating to if you check with me). (Maiya Kozey) DISCLAIMER | DMCA EMVPM2ZPWZC8 # PDF « Geschichte Thailands GESCHICHTE THAILANDS To save Geschichte Thailands PDF, make sure you access the link beneath and save the file or have accessibility to additional information that are relevant to GESCHICHTE THAILANDS ebook. Reference Series Books LLC Nov 2011, 2011. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 246x190x13 mm. Neuware - Quelle: Wikipedia. Seiten: 124. Kapitel: Changwat, Siam, Lan Na, Constantine Phaulkon, Königreich Ayutthaya, Gustave Rolin-Jaequemyns, Bunnag, Militärgeschichte von Thailand, Dvaravati, Monthon, Sao Ching Cha, Anuvong, Prasat Preah Vihear, Chroniken von Ayutthaya, Baht, Königreich Thonburi, Rattanakosin, Ho-Kriege, Kampf um Prachuap Khiri Khan, Jeremias Van Vliet, Sukhothai, Bowring-Vertrag, Prayoon Phamonmontri, Wiang Kum Kam, Französisch- Thailändischer Krieg, Chiang Saen, Thammathibet, Mueang Sing, Königreich Chiang Hung, Chamadevi, Suvarnabhumi, Siamesisch-Birmanischer Krieg 1764 1769, Sakkalin, Luis Weiler, Kalahom, Sai Tia Kaphut, Siamesisch-Birmanischer Krieg 1548 1549, Jinakalamali-Chronik, Siamesisch- Vietnamesischer Krieg 1841 1845, Siamesisch-Birmanischer Krieg 1593 1600, Siamesisch-Birmanischer Krieg 1563 1569, Siamesischer-Laotischer Krieg 1826 1829, Devasathan, -

1 Department of Thai and Eastern Languages Faculty of Humanities

236 CHOPHAYOM JOURNAL Vol.28 No.3 (November - December) 2017 Political Discourses in Isan Stone Inscriptions Mudjalin Luksanawong บทคัดย่อ บทความนี้มีวัตถุประสงค์เพื่อถอดรหัสวาทกรรมการเมืองในศิลาจารึกอีสานสมัยไทย-ลาว จากมุมมองภาษาศาสตร์เชิง วิพากษ์ เพื่อดูความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างศิลาจารึกกับบริบทสังคมผ่านภาษาผลการศึกษาพบว่าลักษณะภาษาในการสร้างวาทกรรมการ เมืองในศิลาจารึกอีสานมีลักษณะที่เด่นชัดในเรื่องรูปแบบตัวอักษรและขนบในการสร้างศิลาจารึก และการเลือกใช้ค�า การผูกประโยค ที่แสดงความสัมพันธ์เชิงโครงสร้างส่วนเนื้อหาของวาทกรรมจะสะท้อนภาพการประกอบสร้างอ�านาจและความชอบธรรมในสังคม ของกลุ่มบุคคล 3 กลุ่ม คือ กลุ่มของกษัตริย์และขุนนางผู้มีอ�านาจสูงสุด กลุ่มพระสงฆ์ และกลุ่มประชาชน ความสัมพันธ์เชิงอ�านาจ ระหว่างบุคคลทั้งสามชนชั้นนี้ยังแสดงให้เห็นความสัมพันธ์ของอ�านาจระหว่างมนุษย์กับมนุษย์ และมนุษย์กับความเชื่ออีกด้วย ความสัมพันธ์เชิงอ�านาจเหล่านี้ไม่ได้ถูกน�าเสนอโดยตรงแต่ซ่อนอยู่ในตัวสารที่ต้องผ่านการถอดรหัสและการตีความ และจะต้องอาศัย ปริบททางสังคมในสมัยนั้นเป็นแนวทางในการพิจารณา ค�ำส�ำคัญ : วาทกรรม ศิลาจารึก อีสาน Abstract This purpose of this article was to analyze political discourses in Isan Stone Inscriptions during Tai - Lao reign from the view of critical linguistics in order to explain relations between the stone inscriptions and the contexts of society through language.From the study, it was found that the outstanding characteristics of the language used to create political discourses in Isan Stone Inscriptions were character styles, tradition of stone inscription creations, word choices, andsentence constructions which showed structural relations. -

Special Issue 2, August 2015

Special Issue 2, August 2015 Published by the Center for Lao Studies ISSN: 2159-2152 www.laostudies.org ______________________ Special Issue 2, August 2015 Information and Announcements i-ii Introducing a Second Collection of Papers from the Fourth International 1-5 Conference on Lao Studies. IAN G. BAIRD and CHRISTINE ELLIOTT Social Cohesion under the Aegis of Reciprocity: Ritual Activity and Household 6-33 Interdependence among the Kim Mun (Lanten-Yao) in Laos. JACOB CAWTHORNE The Ongoing Invention of a Multi-Ethnic Heritage in Laos. 34-53 YVES GOUDINEAU An Ethnohistory of Highland Societies in Northern Laos. 54-76 VANINA BOUTÉ Wat Tham Krabok Hmong and the Libertarian Moment. 77-96 DAVID M. CHAMBERS The Story of Lao r: Filling in the Gaps. 97-109 GARRY W. DAVIS Lao Khrang and Luang Phrabang Lao: A Comparison of Tonal Systems and 110-143 Foreign-Accent Rating by Luang Phrabang Judges. VARISA OSATANANDA Phuan in Banteay Meancheay Province, Cambodia: Resettlement under the 144-166 Reign of King Rama III of Siam THANANAN TRONGDEE The Journal of Lao Studies is published twice per year by the Center for Lao Studies, 65 Ninth Street, San Francisco, CA, 94103, USA. For more information, see the CLS website at www.laostudies.org. Please direct inquiries to [email protected]. ISSN : 2159-2152 Books for review should be sent to: Justin McDaniel, JLS Editor 223 Claudia Cohen Hall 249 S. 36th Street University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104 Copying and Permissions Notice: This journal provides open access to content contained in every issue except the current issue, which is open to members of the Center for Lao Studies. -

Yangon University of Economics Master of Development Studies Programme

YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS MASTER OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES PROGRAMME CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES OF TOURISM DEVELOPMENT IN MYANMAR AMONG CLMV COUNTRIES (CAMBODIA, LAO PDR, MYANMAR, VIETNAM) KHINE MYINTZU TUN EMDevS – 9 (15th Batch) NOVEMBER, 2019 1 YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS MASTER OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES PROGRAMME CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES OF TOURISM DEVELOPMENT IN MYANMAR AMONG CLMV COUNTRIES (CAMBODIA, LAO PDR, MYANMAR, VIETNAM) A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Development Studies (MDevS) Degree Supervised by: Submitted by: Dr. Khin Thida Nyein Khine Myintzu Tun Professor Roll No.9 Department of Economics EMDevS-15th Batch Yangon University of Economics (2017-2019) NOVEMBER, 2019 i YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS MASTER OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES PROGRAMME This is to certify that this thesis entitled “Challenges and Opportunities of Tourism Development in Myanmar among CLMV countries” submitted as a partial fulfilment towards the requirements for the degree of Master of Development Studies, has been accepted by the Board of Examiners. BOARD OF EXAMINERS 1. Dr. Tin Win Rector Yangon University of Economics (Chief Examiner) 2. Dr. Nilar Myint Htoo Pro – Rector Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) 3. Dr. Kyaw Min Htun Pro – Rector (Retd.) Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) 4. Dr. Cho Cho Thein Professor and Head Department of Economics Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) 5. Dr. Tha Pye Nyo Professor Department of Economics Yangon University of Economics (Examiner) NOVEMBER, 2019 ii ABSTRACT Being recognized the noticeable change of Globalization, Tourism Development is the fruitful result of business movement from globalization rapidly. Within ASEAN, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam (CLMV) countries have the most potential in tourism development. -

Appendix Appendix

APPENDIX APPENDIX DYNASTIC LISTS, WITH GOVERNORS AND GOVERNORS-GENERAL Burma and Arakan: A. Rulers of Pagan before 1044 B. The Pagan dynasty, 1044-1287 C. Myinsaing and Pinya, 1298-1364 D. Sagaing, 1315-64 E. Ava, 1364-1555 F. The Toungoo dynasty, 1486-1752 G. The Alaungpaya or Konbaung dynasty, 1752- 1885 H. Mon rulers of Hanthawaddy (Pegu) I. Arakan Cambodia: A. Funan B. Chenla C. The Angkor monarchy D. The post-Angkor period Champa: A. Linyi B. Champa Indonesia and Malaya: A. Java, Pre-Muslim period B. Java, Muslim period C. Malacca D. Acheh (Achin) E. Governors-General of the Netherlands East Indies Tai Dynasties: A. Sukhot'ai B. Ayut'ia C. Bangkok D. Muong Swa E. Lang Chang F. Vien Chang (Vientiane) G. Luang Prabang 954 APPENDIX 955 Vietnam: A. The Hong-Bang, 2879-258 B.c. B. The Thuc, 257-208 B.C. C. The Trieu, 207-I I I B.C. D. The Earlier Li, A.D. 544-602 E. The Ngo, 939-54 F. The Dinh, 968-79 G. The Earlier Le, 980-I009 H. The Later Li, I009-I225 I. The Tran, 1225-I400 J. The Ho, I400-I407 K. The restored Tran, I407-I8 L. The Later Le, I4I8-I8o4 M. The Mac, I527-I677 N. The Trinh, I539-I787 0. The Tay-Son, I778-I8o2 P. The Nguyen Q. Governors and governors-general of French Indo China APPENDIX DYNASTIC LISTS BURMA AND ARAKAN A. RULERS OF PAGAN BEFORE IOH (According to the Burmese chronicles) dat~ of accusion 1. Pyusawti 167 2. Timinyi, son of I 242 3· Yimminpaik, son of 2 299 4· Paikthili, son of 3 . -

Luang Prabang: the Spiritual Heart of Laos

Destination Inspiration: The Colorful Laos LUANG PRABANG: ThE SpIRITUAL HEART OF LAOS Luang Prabang is rich in cultural heritage, and and international authorities, a real motivation Luang Prabang is situated in the centre of is known as the seat of Lao culture, with mon- to preserve this wonderfully serene city. The northern Laos. The province has a total popu- asteries, monuments traditional costumes and title is justified not only by the many beauti- lation of just over 400,000 that includes 12 dis- surrounded by many types of nature's beauty. ful temples, but also by its traditional wooden tinct ethnic groups. The Khmu are the largest In 1995 unESCO declared Luang Prabang a dwellings, the old colonial style houses and the ethnic group in the province and make up the world Heritage Site. This distinction confirms, natural environment that encases it in a per- majority (about 44%) of the provincial popula- through the concerted action of local, national fect harmony of plant and stone. tion. They are a Mon-Khmer speaking people February, 2011 — 56 — Destination Inspiration: The Colorful Laos known for their knowledge of the forest, and to Muang xieng Dong xieng Thong by local xang broke up into three separate Kingdoms; they are believed to be the original inhabitants inhabitants. Shortly thereafter, King Fa ngum Vientiane, Champasack and Luang Prabang. of Laos. The Hmong are the second most popu- accepted a golden buddha image called the by the late 19th century Luang Prabang was lous ethnic minority. Pha bang as a gift from the Khmer monarchy under attack by marauding black Flag bandits archaeological evidence suggests that Luang and the thriving city-state became known as who destroyed many sacred buddha images, Prabang has been inhabited since at least Luang Prabang.