Karl Marx's Grundrisse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Karl Marx

LENIN LIBRARY VO,LUME I 000'705 THE TEA~HINGS OF KARL MARX • By V. I. LENIN FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY U8AARY SOCIALIST - LABOR COllEClIOK INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS 381 FOURTH AVENUE • NEW YORK .J THE TEACHINGS OF KARL MARX BY V. I. LENIN INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS I NEW YORK Copyright, 1930, by INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS CO., INC. PRINTED IN THE U. S. A. ~72 CONTENTS KARL MARX 5 MARX'S TEACHINGS 10 Philosophic Materialism 10 Dialectics 13 Materialist Conception of History 14 Class Struggle 16 Marx's Economic Doctrine . 18 Socialism 29 Tactics of the Class Struggle of the Proletariat . 32 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF MARXISM 37 THE TEACHINGS OF KARL MARX By V. I. LENIN KARL MARX KARL MARX was born May 5, 1818, in the city of Trier, in the Rhine province of Prussia. His father was a lawyer-a Jew, who in 1824 adopted Protestantism. The family was well-to-do, cultured, bu~ not revolutionary. After graduating from the Gymnasium in Trier, Marx entered first the University at Bonn, later Berlin University, where he studied 'urisprudence, but devoted most of his time to history and philosop y. At th conclusion of his uni versity course in 1841, he submitted his doctoral dissertation on Epicure's philosophy:* Marx at that time was still an adherent of Hegel's idealism. In Berlin he belonged to the circle of "Left Hegelians" (Bruno Bauer and others) who sought to draw atheistic and revolutionary conclusions from Hegel's philosophy. After graduating from the University, Marx moved to Bonn in the expectation of becoming a professor. However, the reactionary policy of the government,-that in 1832 had deprived Ludwig Feuer bach of his chair and in 1836 again refused to allow him to teach, while in 1842 it forbade the Y0ung professor, Bruno Bauer, to give lectures at the University-forced Marx to abandon the idea of pursuing an academic career. -

My Years of Exile

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com մենամյա ՈՐՍՆԻ ա) 20837 ARTES SCIENTIA LIBRARY VERITAS OF THE UNIVERSITY MICHIGAN OF R2 TIEBOR SI -QURRISPENINSULAMAMENAM 94JBUSONG 148 276 2534 A43 1 - 4 , MY YEARS OF EXILE REMINISCENCES OF A SOCIALIST MY YEARS OF EXILE REMINISCENCES OF A SOCIALIST BY EDUARD BERNSTEIN TRANSLATED BY BERNARD MIALL NEW YORK HARCOURT , BRACE AND HOWE 1921 Morrison Soria ! AUTHOR'S PREFACE T the request of the editor of the Weisse Blätter , René Schickele , I decided , in the late autumn A of 1915 , to place on record a few reminiscences of my years of wandering and exile . These reminiscences made their first appearance in the above periodical , and now , with the kind permission of the editor , for which I take this opportunity of expressing my sincere thanks , I offer them in volume form to the reading public , with a few supplementary remarks and editorial revisions . My principal thought , in writing these chapters , as I remarked at the time of their first appearance , and repeat to - day , was to record my impressions of the peoples whose countries have given me a temporary refuge . At the same time I have also made passing allusion to the circumstances which caused me to make the acquaintance of these peoples and countries . And , further , it seemed to me not amiss to add , from time to time , and by the way , a few touches of self - portraiture . -

A Dissertation Entitled Yoshimoto Taka'aki's Karl Marx

A Dissertation Entitled Yoshimoto Taka’aki’s Karl Marx: Translation and Commentary By Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for the requirements for The Doctor of Philosophy in History ________________________ Adviser: Dr. Peter Linebaugh ________________________ Dr. Alfred Cave ________________________ Dr. Harry Cleaver ________________________ Dr. Michael Jakobson ________________________ Graduate School The University of Toledo August 2008 An Abstract of Yoshimoto Taka’aki’s Karl Marx: Translation and Commentary Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for the requirements for The Doctor of Philosophy in History The University of Toledo August 2008 In 1966 the Japanese New Left thinker Yoshimoto Taka’aki published his seminal book on Karl Marx. The originality of this overview of Marx’s ideas and life lay in Yoshimoto’s stress on the young Marx’s theory of alienation as an outgrowth of a unique philosophy of nature, whose roots went back to the latter’s doctoral dissertation. It echoed Yoshimoto’s own reformulation of “alienation” (and Marx’s labor theory of value) as key concept in his theory of literary language (What is Beauty in Language), which he had just completed in 1965, and extended his argument -- ongoing from the mid-1950s -- with Japanese Marxism over questions of literature, politics, and culture. His extraction of the theme of “communal illusion” from the early Marx foregrounds his second major theoretical work of the decade, Communal Illusion, which he started to serialize in 1966 and completed in 1968, and outlines an important theoretical closure to the existential, political, and intellectual struggles he had waged since the end of the ii Pacific War. -

Jenny Marx Du Même Auteur

Jenny Marx Du même auteur Ouvrages divers de Jérôme Fehrenbach Un député picard de Varennes à Waterloo : Louvet de la Somme (1757‑1818), Encrage, 2006 Une famille de la petite bourgeoisie parisienne de Louis XIV à Louis XVIII : les Gaugé et leurs alliances à travers les archives (1680‑1820), L’Harmattan, 2007 Le Général Legrand, d’Austerlitz à la Bérézina, Éditions Soteca, 2012 Les Fehrenbach, 1270‑1970, auto-édition, Copy Média, 2015 La Princesse Palatine, l’égérie de la Fronde, Éditions du Cerf, 2016 Von Galen, un évêque contre Hitler, Éditions du Cerf, 2018 Ouvrages de Jérôme Fehrenbach en collaboration Un cœur allemand – Karl von Wendt (1911‑1942), un catholique d’une guerre à l’autre, avec Florence Fehrenbach, Éditions Privat, 2006 Nous voulions tuer Hitler, avec Philipp von Boeselager, Éditions Perrin, 2008 Les Boca, avec Olivier Boca, auto-édition, Copy Média, 2018 Ballons montés – Correspondance et tendresse conjugale pendant l’année terrible (septembre 1870‑mai1871), avec Pierre Allorant, Éditions du Cerf, 2019 Jérôme Fehrenbach Jenny Marx LA TENTATION BOURGEOISE ISBN : 978-2-3793-3486-3 Dépôt légal – 1re édition : mars, 2021 © Passés composés / Humensis, 2021 170 bis, boulevard du Montparnasse, 75680 Paris cedex 14 Le code de la propriété intellectuelle n’autorise que « les copies ou reproductions strictement réser- vées à l’usage privé du copiste et non destinées à une utilisation collective » (article L 122-5) ; il auto- rise également les courtes citations effectuées pour un but d’exemple ou d’illustration. En revanche, « toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle, sans le consentement de l’auteur ou de ses ayants droit ou ayants cause, est illicite » (article L 122-4). -

Originalfassung Des an Den Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin Übergebenen Manuskripts 2 3

1 Jürgen Wolfgang Mäuer Jenny Marx oder: Leben wider den Zeitgeist Originalfassung des an den Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin übergebenen Manuskripts 2 3 Vorwort 5 Das Leben der Jenny Marx, geb. von Westphalen Herkunft: 1700 bis 1814 9 Kindheit: 1814 bis 1830 12 Jugend: 1830 bis 1843 16 Paris 1843 bis 1845 25 Brüssel 1845 bis 1848 31 Paris, 2. Aufenthalt 1848 39 Köln 1848 41 London 1849 bis 1851 46 Frederick Demuth, 1851 50 Sekretär von Karl Marx, 1851 53 Schicksalsschläge, 1854 57 Veränderungen, 1856 60 Neue Perspektiven – neue Not, 1861 65 Bessere Zeiten, 1864 71 Das Kapital, 1866 74 Materielle Sicherheit, 1869 77 Das ruhige Leben, 1873 84 Jennys lange Krankheit, 1876 87 Briefe im Internet Ordner Briefe Jenny Marx in Zaltbommel an Karl Marx in London, August 1850 Jenny Marx in London an Friedrich Engels in Manchester, 27. April 1853 Jenny Marx in London an Friedrich Engels in Manchester, 12. Juli 1870 Theaterkritik im Internet Ordner Dokumente Jenny Marx ´ Londoner Saison Anhang Literatur 91 Cronik im Internet Ordner Dokumente 4 5 Vorwort Jenny Marx, das war doch die Ehefrau von …? Oder war es die Schwester – oder doch die Tochter? Als ich meinen ersten Kontakt mit der Jenny-Marx-Gesellschaft für politische Bildung e.V. aufnahm, wusste ich fast nichts über das Leben von Jenny von Westphalen. Als Vorsitzender dieser parteinahen Landesstiftung war es für mich eine Selbstverständlichkeit, mich mit dem Leben der Namensgeberin auseinanderzusetzen Ein spannendes Erlebnis, denn Jenny Marx war wesentlich mehr als die Frau von … ! Jenny von Westphalen war eine faszinierende Frau voller Widersprüche. Intelligent und hoch gebildet, wie nur wenige Frauen ihrer Zeit. -

Ernst-Bloch-On-Karl-Marx.Pdf

ON KARL MARX ERNST BLOCH AN AZIMUTH BOOK HERDER AND HERDER Azimuth defines direction by generating an arc between a fixed point and a variable, between the determined truths of the past and the unknown data of the future. 197 1 HERDER AND HERDER NEW YORK 232 Madison Avenue, New York 100 16 Original edition: Uber Karl Marx, © 1968 by Suhrkamp Verlag; from Das Prinzip Hoffnung, 3 vols. (passim), © 1959, Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main. Translated by John Maxwell. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-87750 English translation © 1971 by Herder and Herder, Inc. Manufactured in the United States "._ CONTENTS Marx as a Student 9 Karl Marx and Humanity: The Material of Hope 16 Man and Citizen in Marx 46 Changing the WorId: Marx's Theses on Feuerbach 54 Marx and the Dialectics of Idealism 106 The University, Marxism, and Philosophy 118 The Marxist Concept of Science 141 Epicurus and Karl Marx 153 Upright Carriage, Concrete Utopia 159 MARX AS A STUDENT True growth is always open and youthful, and youth implies growth. Youth, like growth, is restless; growth, like youth, would lay the future open in the present. Apathy is their common enemy, and they are allies in the fight for that which has never been but is now coming into its own. Now is its day; and its day is as young and as vital as those who proclaim it and keep faith with it. If we look back to the very dawn of our daytime, we look back to the young Marx in his first years of intellectual ferment. -

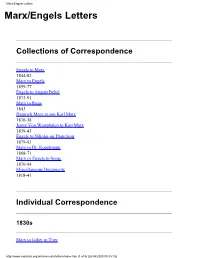

Marx/Engels Letters Marx/Engels Letters

Marx/Engels Letters Marx/Engels Letters Collections of Correspondence Engels to Marx 1844-82 Marx to Engels 1859-77 Engels to August Bebel 1873-91 Marx to Ruge 1843 Heinrich Marx to son Karl Marx 1836-38 Jenny Von Westphalen to Karl Marx 1839-43 Engels to Nikolai-on Danielson 1879-93 Marx to Dr. Kugelmann 1868-71 Marx or Engels to Sorge 1870-94 Miscellaneous Documents 1818-41 Individual Correspondence 1830s Marx to father in Trier http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/letters/index.htm (1 of 5) [26/08/2000 00:28:15] Marx/Engels Letters November 10, 1837 1840s Marx to Carl Friedrich Bachman April 6, 1841 Marx to Oscar Ludwig Bernhard Wolf April 7, 1841 Marx to Dagobert Oppenheim August 25, 1841 Marx To Ludwig Feuerbach Oct 3, 1843 Marx To Julius Fröbel Nov 21, 1843 Marx and Arnold Ruge to the editor of the Démocratie Pacifique Dec 12, 1843 Marx to the editor of the Allegemeine Zeitung (Augsburg) Apr 14, 1844 Marx to Heinrich Bornstein Dec 30, 1844 Marx to Heinrich Heine Feb 02, 1845 Engels to the communist correspondence committee in Brussels Sep 19, 1846 Engels to the communist correspondence committee in Brussels Oct 23, 1846 Marx to Pavel Annenkov Dec 28, 1846 1850s Marx to J. Weydemeyer in New York (Abstract) March 5, 1852 1860s http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/letters/index.htm (2 of 5) [26/08/2000 00:28:15] Marx/Engels Letters Marx to Lasalle January 16, 1861 Marx to S. Meyer April 30, 1867 Marx to Schweitzer On Lassalleanism October 13, 1868 1870s Marx to Beesly On Lyons October 19, 1870 Marx to Leo Frankel and Louis Varlin On the Paris Commune May 13, 1871 Marx to Beesly On the Commune June 12, 1871 Marx to Bolte On struggles witht sects in The International November 23, 1871 Engels to Theodore Cuno On Bakunin and The International January 24, 1872 Marx to Bracke On the Critique to the Gotha Programme written by Marx and Engels May 5, 1875 Engels to P. -

Memória, Resistência E Intelectualidade Em Jenny Marx

Memória, Resistência e Intelectualidade em Jenny Marx THAIS DOMINGOS DOS SANTOS RODRIGUES* Resumo: Este artigo tem por objetivo elucidar a potência de resistência e intelectualidade de Jenny von Westphalen, colocando em debate o papel da mulher na produção de conhecimento e seus atrofiamentos numa sociedade patriarcal. Utilizamos como metodologia a análise de produções recentes e mais antigas como a biografia de Mary Gabriel – Amor e Capital: A Saga Familiar de Karl Marx e o Nascimento de Uma Revolução (2013), o filme O jovem Karl Marx (2017) de Raoul Peck e a biografia de Françoise Giroud: Jenny Marx ou a Mulher do Diabo (1996). A partir dessas obras procuramos elucidar uma Jenny que vai além da esposa, da mãe de sete filhos, da “bela prussiana”, mas com toda sua complexidade de uma grande revolucionária e peça fundamental para a elaboração da teoria marxiana, ou seja, com base nessas três linguagens oriundas de locais diferentes e em conjunto com a revisão bibliográfica analisamos as memórias de Jenny Marx enquanto mulher, comunista e intelectual. Encarando que a memória e o discurso estão sempre em disputa, trazemos o debate da historiografia feminina e a invisibilidade das mulheres na história apontando como meio de possibilidade de emergência de novas narrativas a utilização da história oral. Palavras-chave: Jenny Marx; Mulheres; História. Abstract: This article has as objective clarify the potency of resistance and intellectuality of Jenny von Westphalen, setting in debate the woman role in the production of knowledge and their atrophy in a patriarchal society. We resort as methodology the analysis of recent productions and oldest ones like the biography by Mary Gabiel - Love and Capital: Karl and Janny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution(2013), the movie The Young Karl Marx (2017) by Raoul Peck and the biography by Françoise Giroud: Jenny Marx or la femme du diable(1996). -

Annual Report 2016 L Urg Rosa Uxemb Stiftung

AnnuAl RepoRt 2016 Rosa LuxembuRg stiftung tiftung s g- R Rosa-Luxembu AnnuAl report 2016 of the Rosa-LuxembuRg-stiftung 1 contents editoriAl 4proJect FundinG 42 Focus: tHe leFt And clAss 6 tHe scHolArsHip depARTMent 52 New Class Politics 6 Interview on the Current Situation of Critical Research in Turkey 54 Great Struggles, Small Victories—The Foundation’s Work in Europe 9 The Culturalization of the Class Struggle 55 The European ports—Marketplaces of Globalization 10 Developing Strategies to Help Unions Assert their Interests 11 tHe politicAl coMMunicAtion depARTMent 58 The Electoral Success of the AfD is not a Class Issue 11 Rosa at the Book Fair: A Report from the 68th Frankfurt Book Fair 59 The Leipzig Middle Study—Media Coverage 12 Smart Words: A Critical Lexicon of Digitization 60 Project Sponsorship and Publications Linked to the Focus 13 Selected Publications by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung 61 tHe institute For criticAl sociAl AnAlYsis 14 tHe ArcHiVes And liBrArY 62 Fellowships 15 “Unboxing—Algorithms, Data and Democracy” 16 neWs FroM tHe FoundAtion 64 48 Hours of Peace—Workshops on Peace, Foreign, and Security Policies 17 A Question of Patience: New Building Projects Enter a Critical Phase 64 “Connecting Class”—A joint edition produced by Jacobin and LuXemburg 18 Not safe at all—A Critique of the Idea of Safe Countries of Origin 65 Luxemburg Lectures 19 Life as a Marxist Historian: On the Passing of Kurt Pätzold (1930–2016) 66 The Last Journey: Hans-Jürgen Krysmanski (1935–2016) 66 tHe AcAdeMY For politicAl educAtion 20 A Passionate -

Requiem for Marx and the Social and Economic Systems Created in His Name

REQUIEM for RX Edited with an introduction by Yuri N. Maltsev ~~G Ludwig von Mises Institute l'VIISes Auburn University, Alabama 36849-5301 INSTITUTE Copyright © 1993 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute All rights reserved. Written permission must be secured from the publisher to use or reproduce any part of this book, except for brief quotations in critical review or articles. Published by Praxeology Press of the Ludwig von Mises Institute, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama 36849. Printed in the United States ofAmerica. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 93-083763 ISBN 0-945466-13-7 Contents Introduction Yuri N. Maltsev ........................... 7 1. The Marxist Case for Socialism David Gordon .......................... .. 33 2. Marxist and Austrian Class Analysis Hans-Hermann Hoppe. .................. .. 51 3. The Marx Nobody Knows Gary North. ........................... .. 75 4. Marxism, Method, and Mercantilism David Osterfeld ........................ .. 125 5. Classical Liberal Roots ofthe Marxist Doctrine of Classes Ralph Raico ........................... .. 189 6. Karl Marx: Communist as Religious Eschatologist Murray N. Rothbard 221 Index 295 Contributors 303 5 The Ludwig von Mises Institute gratefully acknowledges the generosity ofits Members, who made the publication of this book possible. In particular, it wishes to thank the following Patrons: Mark M. Adamo James R. Merrell O. P. Alford, III Dr. Matthew T. Monroe Anonymous (2) Lawrence A. Myers Everett Berg Dr. Richard W. Pooley EBCO Enterprises Dr. Francis Powers Burton S. Blumert Mr. and Mrs. Harold Ranstad John Hamilton Bolstad James M. Rodney Franklin M. Buchta Catherine Dixon Roland Christopher P. Condon Leslie Rose Charles G. Dannelly Gary G. Schlarbaum Mr. and Mrs. William C. Daywitt Edward Schoppe, Jr. -

An All Too Human Communism

chapter 5 An All Too Human Communism 1 A Generalised Inversion When Marx left the editorship of the Rheinische Zeitung on 17 March 1843, the fate of the Cologne paper was inexorably sealed. Due to the radical nature of the liberalism that inspired the paper under Marx’s editorship, the Prussian government had for some time already effectively decided upon its suppres- sion. However, officially, it was only a ministerial order of 21 January 1843 that stated that the Rheinische Zeitung would cease publication by 31 March of the same year. This accordingly took place, despite Marx’s efforts to obtain a revoc- ation of the government decision and the petitions submitted by the citizens of Cologne and other Rhineland cities, as well an appeal on the part of the paper’s shareholders to the Prussian sovereign.1 The closure of the Rheinische Zeitung resulted in a determining change in both the public and private spheres of the young intellectual’s life. He was now 25 years old. Weighty issues, both practical and theoretical, loomed on the horizon for him. The previous year, after the death of his brother Hermann,2 difficulties arose with his mother, Henriette, who, wanting to see him take up a secure and advantageous profession, had already refused both any finan- cial assistance and access to his paternal inheritance. On the other hand, his engagement to Jenny von Westphalen had existed since the autumn of 1836 1 During the discussion on this of the General Meeting of the Shareholders of the Rheinische Zeitung, Jung, one of the directors, declared that ‘the newspaper has prospered in its present form, it has gained a surprising number of readers with astonishing rapidity’ (mecw 1, p. -

Marx, Engels, and the Abolition of the Family - Richard Weikart*

History of European Ideas, Vol. 18, No. 5, pp. 657-672, 1994 0191-6599 (93) E0194-6 _ . Copyright c 1994 Elseyier Science Ltd Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved 0191-6599/94 $7.00+ 0.00 MARX, ENGELS, AND THE ABOLITION OF THE FAMILY - RICHARD WEIKART* 'It is a peculiar fact' stated Engels a few months after Marx died, 'that with every great revolutionary movement the question of 'free love' comes to the foreground'.' By the mid- to late-nineteenth century it was clear to advocates and opponents alike that many socialists shared a propensity to reject the institution of the family in favour of 'free love', if not in practice, at least as an ideal. The Prussian and German Reich governments tried to muzzle the socialist threat to the family by drafting legislation in 1849,1874,1876 and 1894, outlawing, among other things, assaults on the family.2 However, the Anti-Socialist Law that Bismarck managed to pass in 1878 contained no mention of the family. The Utopian Socialists Charles Fourier and Robert Owen had preceded Marx and Engels in their rejection of traditional family relationships, and many nineteenth-century leftists followed their cue. The most famous political leader of the German socialists, August Bebel—though he was a staunch Marxist— wrote his immensely popular book, Die Frau und der Sozialismus, under the influence of Fourier's ideas. However, not all socialists in the nineteenth century were anti-family. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who wielded great influence in French socialist and anarchist circles, wanted to retain the family institution, which he loved and revered.