Ernst-Bloch-On-Karl-Marx.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loneliness of Human in the Philosophy of Ernst Bloch Culture

SHS Web of Conferences 72, 03002 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf /20197203002 APPSCONF-2 019 Loneliness of human in the philosophy of Ernst Bloch culture Pavel Lyashenko 1, and Maxim Lyashchenko 1 1Orenburg State University, 460018, Orenburg, Russia Abstract. The problem of loneliness from the view point of philosophical and anthropological knowledge acquires special significance, is filled with new content in connection with the unfolding of the modern society transformation processes, as a result, with a new stage in the reappraisal of the modern culture utopian consciousness. At the same time, Ernst Bloch's culture philosophy induce particular scientific interest, according to which the meaningful status of utopia is determined by the fact that it forms a certain ideal image of the human world, which is the space of culture as a whole. In this regard, the study of the loneliness phenomenon in Ernst Bloch culture philosophy allows us to identify the socio-cultural mechanisms of loneliness, as well as key factors in the development of modern society, leading the person to negation and the destruction of his being. 1 Introduction Like a lot of factors that form the everyday world of human, loneliness, culture, utopia belong to the phenomena of human being that are complex for scientific and philosophical comprehension. Turning to the theoretical heritage of the past and modern philosophical research leads to mutually exclusive judgments about loneliness, about culture, and about utopia. Sometimes we come to the idea of the incompatibility of these phenomena, in the absence of any strong and stable connection between them. -

Through the Brook of Fire: Marx'sconceptofspecies- Being Andhisbreakwith Feuerbach

1 WALKER THROUGH THE BROOK OF FIRE: MARX’S CONCEPT OF SPECIES- BEING AND HIS BREAK WITH FEUERBACH Grayson Shade Walker Supervised by Dr. Gabriel Gottlieb 30 April 2021 2 WALKER 1 | INTRODUCTION Once upon a time a valiant fellow had the idea that men were drowned in water only because they were possessed with the idea of gravity. If they were to knock this notion out of their heads, say by stating it to be a superstition, a religious concept, they would be sublimely proof against any danger from water. His whole life long he fought against the illusion of gravity, of whose harmful results all statistic brought him new and manifold evidence. This valiant fellow was the type of the new revolutionary philosophers in Germany.1 -- Karl Marx The task of this paper is to re-visit a concept that has long escaped proper clarification: Gattungswesen, or species-being. Many scholars have often assumed that the concept has no bearing on Marx’s later developments, or that it invariably bears the baggage of idealistic humanism not yet shorn by the younger Marx.2 While there may be traces of an incipient idealism in the early Marx—a product of his own post-Hegelian milieu—this paper will show how Marx inherits Feuerbach’s concept of species-being and, by overcoming its limitations, arrives at a new concept of humanity. I will show how Feuerbach fails to materialistically inverse Hegel, and how this failure leads him to a concept of man that is ultimately ahistorical—as it fixes a human essence beyond human history—and is idealist, to the extent that it begins from abstractions from the world. -

Of Ernst Bloch Michael Löwy

C The Principle of Hope from Ernst Bloch is undoubtedly one C R R I of the major works of emancipatory thought in the twentieth century. I Romanticism, Marxism S Monumental (more than 1600 pages), it occupied the author for a large S I I S part of his life.Written during his exile in United States, from 1938 to S 1947, it would be reviewed for the first time in 1953 and a second in & & and Religion in the 1959. Following his condemnation as “revisionist” by authorities of the C C R German Democratic Republic, the author eventually left East Germany R I in 1961. I “Principle of Hope” of T T I Nobody had ever written a book like this, stirring in the same I Q breath the visionary pre-Socratic and Hegelian alchemy, the new Q U U Ernst Bloch E Hoffmann, the serpentine heresy and messianism of Shabbataï Tsevi, E Schelling’s philosophy of art, Marxist materialism, Mozart’s operas V V O and the utopias of Fourier. Open a page at random: it is about the man O L. L. 2 of Renaissance, the concept of (material) substance in Parecelse and 2 Jakob Böhme, of the Holy Family in Marx, of the doctrine of knowledge I I S in Giordano Bruno and the book on the Reform of Knowledge of S S Spinoza. The erudition of Bloch is so encyclopedic that very few readers S Michael Löwy U U E are capable of judging the entirety of each theme developed in the three E #1 volumes of the book. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ “From the Theses on Feuerbach to the Philosophy of Praxis: Marx, Gramsci, Philosophy and Politics” Bernstein, Aaron Jacob Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 1 From the Theses on Feuerbach to the Philosophy of Praxis: Marx, Gramsci, Philosophy and Politics Aaron Bernstein PhD European Studies 2 Abstract In recent years, there has been a growing literature on Gramsci’s conception of the philosophy of praxis, and specifically the centrality of Marx within it. -

1 Marx 1845 Or the Fateful Rejection of Anschauung Abstract One of Karl

Marx 1845 or the Fateful Rejection of Anschauung Abstract One of Karl Marx’s strongest condemnation is that of Ludwig Feuerbach’s intuitive- contemplative materialism in his Theses of 1845. This condemnation famously leads him to an understanding of human activity as purely objective and of “revolution” as praxis, that is, as a “practical-critical” activity exclusively based on reason and reason alone. The question that is rarely asked about this condemnation is this: what is lost in this abandonment of the intuitive-contemplative on the way to historical materialism? The aim behind this question is purely speculative. It does not intend to provide yet again a historical reading of this famous turning point in Marx’s move away from Feuerbach. It simply intends to see whether something could be gained instead from revisiting Feuerbach’s understanding of the intuitive- contemplative and whether this could allow us to move beyond the 21st Century deadlock of Marx’s “rational praxis.” In terms of reading, the essay will concentrate not only on Marx’s Theses and the “works of the break,” but also on key aspects of Feuerbach’s understanding of intuition-contemplation, as well as contemporary readings of this major turning point in history, especially those in the French Marxist tradition such as Bloch, Henry, Althusser, Macherey, and of course, Balibar. Keywords Marx, Feuerbach, Praxis, Intuition, Anschauung, Materialism Introduction: The Condemnation One of Karl Marx’s strongest condemnation is that of Ludwig Feuerbach’s intuitive- contemplative materialism in his famous Theses of 1845. The disapproval is crystal clear: “[Feuerbach] does not grasp the significance of ‘revolutionary,’ of ‘practical-critical,’ activity.” (Marx and Engels 2008, 69). -

In the Matter of Marxism

03-Tilley-3290-Ch01.qxd 11/17/2005 6:57 PM Page 13 1 IN THE MATTER OF MARXISM Bill Maurer The real unity of the world consists in its have insisted on an account of actually existing materiality, and this is proved not only by a few ‘men’ in their real, material conditions of exis- juggled phrases, but by a long and wearisome tence. Reactions against abstraction in theory development of philosophy and natural science. more recently often explicitly or implicitly (Engels, Anti-Dühring, 1877) invoke the Marxist heritage as both a theoreti- cal formation and an agenda for oppositional You make me feel mighty real. political practice. As Marx wrote in his eleventh thesis on Feuerbach, ‘The philosophers have (Sylvester, 1978) only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.’ Or, as a colleague once put it to me, ‘Derrida never helped save a WHAT’S THE MATTER WITH Guatemalan peasant.’ MARXISM? This chapter uses a narrow delineation of the field of Marxist-inspired debate and critique, emphasizing those anthropologists (and, to a It is difficult to think about materiality, or to lesser extent, archaeologists) who explicitly think materially about the social, without invoke Marxism in its various guises and who thinking about Marxism. The Cold War led seek in Marxist theories a method and a theory many scholars in the West to use ‘materialism’ for thinking materially about the social. The as a code word for Marxism for much of the chapter pays particular attention to the instances twentieth century. More recently, in certain when such authors attempt to think critically quarters of social scientific thought, materiality about what difference it makes to stress mate- stands in for the empirical or the real, as against riality and to think ‘materially’. -

A Dissertation Entitled Yoshimoto Taka'aki's Karl Marx

A Dissertation Entitled Yoshimoto Taka’aki’s Karl Marx: Translation and Commentary By Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for the requirements for The Doctor of Philosophy in History ________________________ Adviser: Dr. Peter Linebaugh ________________________ Dr. Alfred Cave ________________________ Dr. Harry Cleaver ________________________ Dr. Michael Jakobson ________________________ Graduate School The University of Toledo August 2008 An Abstract of Yoshimoto Taka’aki’s Karl Marx: Translation and Commentary Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for the requirements for The Doctor of Philosophy in History The University of Toledo August 2008 In 1966 the Japanese New Left thinker Yoshimoto Taka’aki published his seminal book on Karl Marx. The originality of this overview of Marx’s ideas and life lay in Yoshimoto’s stress on the young Marx’s theory of alienation as an outgrowth of a unique philosophy of nature, whose roots went back to the latter’s doctoral dissertation. It echoed Yoshimoto’s own reformulation of “alienation” (and Marx’s labor theory of value) as key concept in his theory of literary language (What is Beauty in Language), which he had just completed in 1965, and extended his argument -- ongoing from the mid-1950s -- with Japanese Marxism over questions of literature, politics, and culture. His extraction of the theme of “communal illusion” from the early Marx foregrounds his second major theoretical work of the decade, Communal Illusion, which he started to serialize in 1966 and completed in 1968, and outlines an important theoretical closure to the existential, political, and intellectual struggles he had waged since the end of the ii Pacific War. -

Jenny Marx Du Même Auteur

Jenny Marx Du même auteur Ouvrages divers de Jérôme Fehrenbach Un député picard de Varennes à Waterloo : Louvet de la Somme (1757‑1818), Encrage, 2006 Une famille de la petite bourgeoisie parisienne de Louis XIV à Louis XVIII : les Gaugé et leurs alliances à travers les archives (1680‑1820), L’Harmattan, 2007 Le Général Legrand, d’Austerlitz à la Bérézina, Éditions Soteca, 2012 Les Fehrenbach, 1270‑1970, auto-édition, Copy Média, 2015 La Princesse Palatine, l’égérie de la Fronde, Éditions du Cerf, 2016 Von Galen, un évêque contre Hitler, Éditions du Cerf, 2018 Ouvrages de Jérôme Fehrenbach en collaboration Un cœur allemand – Karl von Wendt (1911‑1942), un catholique d’une guerre à l’autre, avec Florence Fehrenbach, Éditions Privat, 2006 Nous voulions tuer Hitler, avec Philipp von Boeselager, Éditions Perrin, 2008 Les Boca, avec Olivier Boca, auto-édition, Copy Média, 2018 Ballons montés – Correspondance et tendresse conjugale pendant l’année terrible (septembre 1870‑mai1871), avec Pierre Allorant, Éditions du Cerf, 2019 Jérôme Fehrenbach Jenny Marx LA TENTATION BOURGEOISE ISBN : 978-2-3793-3486-3 Dépôt légal – 1re édition : mars, 2021 © Passés composés / Humensis, 2021 170 bis, boulevard du Montparnasse, 75680 Paris cedex 14 Le code de la propriété intellectuelle n’autorise que « les copies ou reproductions strictement réser- vées à l’usage privé du copiste et non destinées à une utilisation collective » (article L 122-5) ; il auto- rise également les courtes citations effectuées pour un but d’exemple ou d’illustration. En revanche, « toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle, sans le consentement de l’auteur ou de ses ayants droit ou ayants cause, est illicite » (article L 122-4). -

Theses on Feuerbach

Marx/Engels Internet Archive Theses On Feuerbach I The chief defect of all hitherto existing materialism - that of Feuerbach included - is that the thing, reality, sensuousness, is conceived only in the form of the object or of contemplation, but not as sensuous human activity, practice, not subjectively. Hence, in contradistinction to materialism, the active side was developed abstractly by idealism -- which, of course, does not know real, sensuous activity as such. Feuerbach wants sensuous objects, really distinct from the thought objects, but he does not conceive human activity itself as objective activity. Hence, in The Essence of Christianity, he regards the theoretical attitude as the only genuinely human attitude, while practice is conceived and fixed only in its dirty-judaical manifestation. Hence he does not grasp the significance of "revolutionary", of "practical-critical", activity. II The question whether objective truth can be attributed to human thinking is not a question of theory but is a practical question. Man must prove the truth — i.e. the reality and power, the this-sidedness of his thinking in practice. The dispute over the reality or non-reality of thinking that is isolated from practice is a purely scholastic question. III The materialist doctrine concerning the changing of circumstances and upbringing forgets that circumstances are changed by men and that it is essential to educate the educator himself. This doctrine must, therefore, divide society into two parts, one of which is superior to society. The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-changing can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionary practice. -

Materialism Against Materialism: Taking up Marx's

https://doi.org/10.37050/ci-20_15 FRIEDER OTTO WOLF Materialism against Materialism Taking up Marx’s Break with Reductionism CITE AS: Frieder Otto Wolf, ‘Materialism against Materialism: Taking up Marx’s Break with Reductionism’, in Materialism and Politics, ed. by Bernardo Bianchi, Emilie Filion-Donato, Marlon Miguel, and Ayşe Yuva, Cultural Inquiry, 20 (Berlin: ICI Berlin Press, 2021), pp. 277–92 <https://doi.org/10.37050/ci-20_15> RIGHTS STATEMENT: Materialism and Politics, ed. by Bernardo Bi- © by the author(s) anchi, Emilie Filion-Donato, Marlon Miguel, and Ayşe Yuva, Cultural Inquiry, 20 (Berlin: Except for images or otherwise noted, this publication is licensed ICI Berlin Press, 2021), pp. 277–92 under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 Interna- tional License. ABSTRACT: This text proposes to overcome the wide-spread error of dismissing Marx’s critique of all materialism before him as being reduc- tionist and therefore philosophically and scientifically unacceptable. Instead, it attempts to create a non-reductionist understanding and practice of materialism in philosophy — especially by referring to key contributions by Althusser and Bhaskar and by criticizing the ‘mater- ialist illusion’ of the early Marx — thereby articulating another key element of the ‘finite Marxism’ defended by the author. KEYWORDS: finite Marxism; after post-modernism; multiple domina- tion; specificity of liberation struggles; historical materialism; capit- alism; power relations The ICI Berlin Repository is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the dissemination of scientific research documents related to the ICI Berlin, whether they are originally published by ICI Berlin or elsewhere. Unless noted otherwise, the documents are made available under a Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.o International License, which means that you are free to share and adapt the material, provided you give appropriate credit, indicate any changes, and distribute under the same license. -

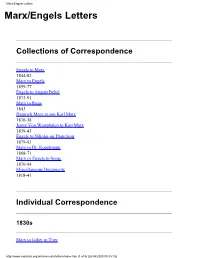

Marx/Engels Letters Marx/Engels Letters

Marx/Engels Letters Marx/Engels Letters Collections of Correspondence Engels to Marx 1844-82 Marx to Engels 1859-77 Engels to August Bebel 1873-91 Marx to Ruge 1843 Heinrich Marx to son Karl Marx 1836-38 Jenny Von Westphalen to Karl Marx 1839-43 Engels to Nikolai-on Danielson 1879-93 Marx to Dr. Kugelmann 1868-71 Marx or Engels to Sorge 1870-94 Miscellaneous Documents 1818-41 Individual Correspondence 1830s Marx to father in Trier http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/letters/index.htm (1 of 5) [26/08/2000 00:28:15] Marx/Engels Letters November 10, 1837 1840s Marx to Carl Friedrich Bachman April 6, 1841 Marx to Oscar Ludwig Bernhard Wolf April 7, 1841 Marx to Dagobert Oppenheim August 25, 1841 Marx To Ludwig Feuerbach Oct 3, 1843 Marx To Julius Fröbel Nov 21, 1843 Marx and Arnold Ruge to the editor of the Démocratie Pacifique Dec 12, 1843 Marx to the editor of the Allegemeine Zeitung (Augsburg) Apr 14, 1844 Marx to Heinrich Bornstein Dec 30, 1844 Marx to Heinrich Heine Feb 02, 1845 Engels to the communist correspondence committee in Brussels Sep 19, 1846 Engels to the communist correspondence committee in Brussels Oct 23, 1846 Marx to Pavel Annenkov Dec 28, 1846 1850s Marx to J. Weydemeyer in New York (Abstract) March 5, 1852 1860s http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/letters/index.htm (2 of 5) [26/08/2000 00:28:15] Marx/Engels Letters Marx to Lasalle January 16, 1861 Marx to S. Meyer April 30, 1867 Marx to Schweitzer On Lassalleanism October 13, 1868 1870s Marx to Beesly On Lyons October 19, 1870 Marx to Leo Frankel and Louis Varlin On the Paris Commune May 13, 1871 Marx to Beesly On the Commune June 12, 1871 Marx to Bolte On struggles witht sects in The International November 23, 1871 Engels to Theodore Cuno On Bakunin and The International January 24, 1872 Marx to Bracke On the Critique to the Gotha Programme written by Marx and Engels May 5, 1875 Engels to P. -

Bloch and Adorno, “Something's Missing,”

Studies in ConteDlporary GerDlan Social Thought Thomas McCarthy, General Editor The Utopian Function of Art Theodor W. Adorno, Against Epistemology: A Metacritique and Literature Theodor W. Adorno, Prisms Karl-Otto Ape!, Understanding and Explanation: A Transcendental-Pragmatic Perspective Selected Essays Richard]. Bernstein, editor, Habermas and Modernity Ernst Bloch, Natural Law and Human Dignity Ernst Bloch, The Principle qf Hope Ernst Bloch, The Utopian Function of Art and Literature: Selected Essays Hans Blumenberg, The Genesis qf the Copernican World Hans Blumenberg, The Legitimacy of the Modern Age Hans Blumenberg, Work on Myth Helmut Dubiel, Theory and Politics: Studies in the Development of Critical Theory John Forester, editor, Critical Theory and Public Life Ernst Bloch David Frisby, Fragments qf Modernity: Theories qf Modernity in the Work qf Simmel, Kracauer and Benjamin Hans-Georg Gadamer, Philosophical Apprenticeships translated by Jack Zipes and Hans-Georg Gadamer, Reason in the Age of Science Frank Mecklenburg Jiirgen Habermas, The Philosophical Discourse qf Modernity: Twelve Lectures Jiirgen Habermas, Philosophical-Political Prqfiles Jiirgen Habermas, editor, Observations on "The Spiritual Situation qfthe Age" HansJoas, G. H. Mead: A Contemporary Re-examination of His Thought Reinhart Koselleck, Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time Herbert Marcuse, Hegel's Ontology and the Theory of Historicity Claus Offe, Contradictions qf the Welfare State Claus Offe, Disorganized Capitalism: Contemporary Traniformations